Chapter 11

Leaning to the Left

In This Chapter

Looking at the liberal past

Looking at the liberal past

Starting a new movement

Starting a new movement

Speaking freely in Berkeley

Speaking freely in Berkeley

Uniting American students

Uniting American students

American college campuses were a focal point and a launching pad of efforts to institute change during the 1960s. However, the ’60s weren’t the beginning of left-wing politics (those embracing Socialist or liberal principles) in 20th-century America. Beginning with the struggle for decent wages and working conditions, labor unions were among the pioneers using direct action, such as strikes, to achieve their aims. People and organizations were also working for peace and integration before the ’60s.

However, prompted by recognition of social injustices, support for the civil rights struggle, and the struggle against the Vietnam War, students throughout the United States organized in the 1960s to further their causes. The two core organizations of the New Left were the free speech movement (FSM) in Berkeley and the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which had chapters all over the country. This chapter looks at the ideas, goals, tactics, and battlegrounds of this left-wing movement.

Left Wing of the American Eagle: Liberal and Socialist Politics before the 1960s

During the early 20th century, in an era called the Progressive Age, workers formed organizations to curb the growing power of big business. Although the progressive movement sought to reform exploitive business practices, others still held onto the ideas of truly remaking the capitalist system. Men such as Eugene Debs, who formed the American Railway Union, tried to curb the excesses of the capitalist giants but failed because business interests had already secured government support. After losing his battle in the famous Pullman strike of 1893, Debs was jailed for obstruction (in this instance, blocking interstate commerce). While in prison, Debs became a Socialist.

After being released from prison, Debs organized the Socialist Party of America. He ran for president in 1900 and received more than 4,000 votes. In 1904 he received 400,000 votes, and in 1908 he received 900,000 votes. In the election of 1912, Debs garnered 6 percent of the popular vote.

Though many people involved in the early labor movements tended toward leftist politics, especially among immigrants who were exposed to Socialist ideas in Europe, eventually the labor movement itself became less radical, except for those such as Debs who followed Socialist ideas in their attempts to improve the lives of workers.

The Palmer Raids

Though Socialists and labor unions both enjoyed a period of growth during World War I, in late 1919 and early 1920 the American Socialist movement was dealt a severe blow with the Palmer Raids. Instituted by U.S. Attorney General Mitchell Palmer, the raids were meant to root out subversive elements in American society by arresting, imprisoning, and deporting suspected Socialists and anarchists. These efforts chilled the Socialist movement for a time. However, the impulse for Socialist principles continued to simmer below the surface.

Pinks and reds in the 1930s and ’40s

During the Great Depression (1929–39), in which many Americans suffered severe economic decline, many political moderates began to embrace Socialist or Communist ideas. Though many would regret this shift later in the repressive climate of the ’50s, during the Depression it made sense. As the leading capitalist nations all suffered real decline, the Communist Soviet Union was experiencing tremendous growth led by Joseph Stalin’s aggressive five-year plans for development.

Leftist politics lost some of their appeal, however, after Franklin Roosevelt’s election in 1932, and the government agencies he created began to relieve some of the hardship. When the Soviet Union supported Adolf Hitler in the late ’30s, some Communists became disillusioned with the movement.

With the end of World War II, the struggle between the Soviet Union and the United States solidified into the cold war (see Chapter 2 for more details about the cold war). To respond to this “red menace” of Communism, the U.S. government introduced a loyalty oath program in 1947, requiring many state, local, and federal employees, including schoolteachers, to sign loyalty oaths stating that they didn’t seek to overthrow the U.S. government, in order to keep their jobs. Fearful of being painted with the “pink” paintbrush (Communist sympathizers were often referred to as “pinkos” — a lighter shade of red), several labor unions began to purge their openly Communist members and distance themselves from anyone that seemed to have Communist sympathies. The House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC; see Chapter 4), founded in 1938, and Senator Joseph McCarthy (see the next section) were at the forefront of the drive to root out Communism.

As such, it stands for the destruction of our American form of government; it stands for the destruction of American democracy; it stands for the destruction of free enterprise; and it stands for the creation of a “Soviet of the United States” and ultimate world revolution.

McCarthyism and the Communist hysteria

After the Soviets exploded an atomic bomb in 1949, and Communist leadership gained power in China in 1949 under Mao Tse Tung, U.S. officials became even more afraid of Socialist or Communist sympathizers. Senator Joseph McCarthy took advantage of this threat by promoting his anti-Communist agenda and threatening to expel Communists in all walks of American life. He spearheaded Senate hearings to expose Communists, during which committee members asked witnesses if they’d ever been Communists and if they knew the names of others who may have been Communists at any time. Many of these witnesses refused to cooperate and, as a result, were blacklisted. In Hollywood, the film industry blacklisted several actors and screenwriters; many never worked again.

In the beginning, playing on people’s fears, McCarthy was successful and had popular support, and he believed he could do anything and point the finger at anyone. He accused people in government and the military of Communism, although these charges were overwhelmingly unfounded. In the end, some of McCarthy’s accusations were so outlandish that Americans began not only to disbelieve him, but they also realized the harm that his fanaticism created. The Senate eventually censured McCarthy on November 9, 1954, for abuse of power, and the Red Scare was over. Years of hard drinking took its toll, and McCarthy died in 1957. McCarthy’s methods created such a backlash that ironically he created a unifying effect among liberals and many moderates.

Another incident that united left-of-center citizens was the conviction and execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. After being found guilty of spying for the Soviet Union, the Rosenbergs were executed for treason. Some people believed that the Rosenbergs were innocent and that their conviction was just another example of the anti-Communist hysteria of the times.

Birthing the New Left

Getting clean for Gene

The New Left adopted some of the more traditional methods of forwarding their agenda in 1968 and 1972, when Eugene McCarthy was vying for the Democratic nomination for president. To promote their antiwar candidate, many antiwar protesters cut their hair and rid their preppy duds of mothballs to “Get Clean for Gene.” However, McCarthy was too liberal for most traditional Democrats and never received the nomination.

Although many New Left activists had liberal parents, their methods still created a generation gap. Parents were more in favor of traditional methods of changing unjust laws (and worried about their kids’ safety, as well as their futures). What made the New Left “new” was that they weren’t allied with the traditional labor movements as a means of creating change within society. Instead, they saw social activism as the agent of transformation of society. Though still leftists, liberals, and even radicals, they were less theory driven than the earlier liberals. Further, they avoided traditional methods of political persuasion, such as lobbying and petitioning congressional members, in favor of more active protests. However, they did actively campaign for candidates that backed their causes, both locally and nationally.

Also, the New Left embraced several points of view. Though some were alienated and cynical, others believed that American society was worth transforming and were willing to risk their education, their future careers, and even their personal freedom, in some cases going to jail to work for peace and justice.

Besides being inspired by the civil rights movement and its nonviolent protests, student radicals were inspired by books and films that criticized conventional, middle-class life. More politically astute students were attracted to works of social criticism by people such as leftist writers Herbert Marcuse, Michael Harrington, and C. Wright Mills, who worked to expose economic and social injustices in the United States.

What were they fighting for?

Throughout the ’60s, New Left causes became larger and more intense. They ranged from the personal to the political, from the local to the national, and eventually, to the global concern for world peace.

Student issues

At first, student protests focused on issues that directly impacted their lives on campus. They demonstrated against and objected to a wide variety of issues, including

Dress codes

Dress codes

In loco parentis (in place of the parent) rules that imposed curfews

In loco parentis (in place of the parent) rules that imposed curfews

Limited dorm visits by the opposite sex (mainly in girls’ dorms)

Limited dorm visits by the opposite sex (mainly in girls’ dorms)

Religious and racial discrimination in sororities and fraternities

Religious and racial discrimination in sororities and fraternities

Required courses that they considered irrelevant to real life

Required courses that they considered irrelevant to real life

The rigid grading system

The rigid grading system

Same-sex dormitories

Same-sex dormitories

Battling the military-industrial complex

Some of the more politically aware students also protested against university involvement with the military, especially as the Vietnam War escalated. Many campuses had large-scale demonstrations against military recruitment on campus and the presence of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC). Across the country, New Left students also fought against university involvement in research that benefited the military-industrial complex and furthered the tensions in the cold war. Though the student protest was aimed at the military, it created a rift between students and university administrators who looked favorably upon such research because it brought funding to the university.

Civil rights

At many northern, largely white campuses, many liberal students joined in the struggle for civil rights in the South. They went south to participate in voter registration drives, desegregation protests, and sit-ins at lunch counters (see Chapter 6). They were arrested and beaten, and some were killed. They marched on Washington, D.C., with Martin Luther King Jr. to show solidarity with blacks. In the segregated South, they witnessed poverty, discrimination, and violence firsthand for the first time.

And end to the War

The Vietnam War was also a personal issue for many of the student protesters. Besides being appalled at the undeclared war waged by their country, most young men in college were of draft age. Although many avoided recruitment with student deferments (which delayed military service while a person was a full-time student) and enlistment in the National Guard (and in some cases alleged medical problems), they were aware of and sometimes embarrassed by the fact that poor and minority groups were often bearing more than their proportionate share of the war burden. However, when the Johnson administration ended student deferments in 1966, opposition to the war and the draft became even more personal, and student anger over the war’s escalation intensified. See Chapter 9 for more on the New Left’s central role in the antiwar movement.

Protesting with direct action

The New Left wasn’t subtle. Using overt, public displays, they attracted press coverage, which made people aware of their concerns. Because New Left students believed that the establishment was corrupt, for the most part they ignored indirect actions, such as lobbying and working to elect favorable candidates. Instead, protesters during the ’60s used direct action, which not only demanded immediate remedies for the problems they saw but also had the advantage of calling attention to their cause. Protest by direct action started with the labor movement in the late 19th century, but throughout the 20th century, activists promoting various causes used direct action to advance women’s suffrage, protest the treatment of veterans, and promote environmental issues.

Protest marches

One of the most visible methods of demanding change was by using massive protest marches. Marchers shouted, sang, carried signs, and talked to the crowd to convert others to their cause (and ideally get them to march along with them). The length of the march wasn’t important — sometimes the protesters walked only a few blocks. However, as soon as they reached their destination, they usually had a huge rally, complete with speeches and music.

Sit-ins

During sit-ins, protesters occupied a building or public area to protest an injustice or demand change, holding their ground until they were either forced out or their demands were met. During the civil rights movement, protesters often sat in at segregated, southern lunch counters and refused to leave (see Chapter 6 for a discussion of the lunch counter sit-ins). Because sit-ins were nonviolent, they usually drew public support, especially if the police tried to forceably remove the protesters. One of the largest student sit-ins was in Sproul Hall, the administration building of the University of California at Berkeley (see the section “The sit-in at Sproul,” later in this chapter). In a lie-in (a variation of a sit-in), demonstrators blocked public access by lying prone across a road or doorway.

Civil disobedience

Civil disobedience took protest up a notch, because protesters usually broke laws (normally those laws that didn’t threaten life and limb) in order to form a blockade or occupy a business or agency. Usually, the protesters were asked to leave and were arrested if they refused, for example. As such, before a civil disobedience event, many protesters figured out how to react to arrest and resist attack.

Protest through the new millennium

The popular protest methods of the ’60s have been used to promote various causes throughout the rest of the 20th century and into the new millennium. Almost every group — gays and lesbians, feminists, the religious right, pro-choice and pro-life activists, environmentalists, vegetarians, animal activists, and antiwar activists — has staged demonstrations at some time or another; they’ve all marched, rallied, sang, and spoke.

One of the largest ’60s-style demonstrations was the protest against the World Trade Organization (WTO) in Seattle, Washington, in late 1999. The protesters came from all over the world and represented a variety of causes and were successful in disrupting the WTO meetings despite the Seattle rain and the police crackdowns.

Although the protests were largely peaceful, a violent minority caused the Seattle police and National Guard to declare a state of emergency, which led to curfews, arrests, and tear gas. The news media coverage was disproportionately attracted to the violent minority (because such depictions sell more papers and raise viewer ratings) and portrayed the protesters as unkempt weirdos, although most of them were simply concerned citizens wanting to make sure that environmental concerns and human rights weren’t lost in the rush toward a worldwide economy.

Fighting for Free Speech

At first glance, in 1960, the University of California at Berkeley seemed an unlikely place for protest. Students were not only some of the best and the brightest but also the epitome of middle-class California. A look at campus photographs at the beginning of the decade shows crew cuts, ponytails (only on the girls), oxford shirts, and penny loafers. Though this image shifted radically by the end of the ’60s, the Vietnam War wasn’t what started the fire — it was an orderly protest against HUAC, one of the most invasive government organizations of the era.

Perhaps if the officials hadn’t reacted so strongly to relatively mild student resistance, the massive demonstrations, sit-ins, and the occupation of the university administration building never would’ve happened.

Berkeley activism before ’63 — HUAC

In May 1960, several student organizations banded together to protest the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) hearings in San Francisco. As we cover in Chapter 4, the goal of HUAC was to root out Communism in the U.S. This issue was very relevant because it heavily involved the aca- demic community (more than 25 percent of the witnesses subpoenaed were teachers). The protesters felt that HUAC encouraged a climate of fear, where people were willing to rat on their friends, neighbors, and colleagues to avoid being called Communists.

Protesters attempted to get in the hearings, but only people with HUAC-issued passes could enter. Unfortunately, the police responded aggressively, even turning fire hoses on the demonstrators. However, the police brutality had just the opposite effect — in the days that followed, San Francisco newspapers printed indignant editorials against the police’s excessive force, and the number of demonstrators increased. The protests didn’t stop the hearings, but in response, HUAC produced a film condemning the demonstrations and labeling the students as Communist dupes. This film, Operation Abolition, was shown throughout the country but had an ironic effect — when the movie was shown at a Harvard ROTC meeting, the promoters found that the student officers actually supported the San Francisco protest.

The university administration tried to appear neutral, but a year later, they showed their bias. They changed the status of SLATE (a campus political party that supported the HUAC protest) from on-campus to off-campus, which limited its ability to organize, distribute materials, and raise funds on campus. The fight between the students and the administration had begun.

Striking for civil rights

Despite their privileged backgrounds, Berkeley students were extremely sympathetic to the civil rights movement. They were concerned not only with integration in the South (and many of them had, in fact, gone south to support the fight for equal rights) but also with economic opportunities right in their own backyard.

In 1963, students banded together with black activists to form a committee to protest hiring discrimination in the San Francisco hotel industry, where blacks were rarely employed as anything other than maids or janitors. The action’s objective was to create an intolerable situation for the hotels, forcing them to respond. Mario Savio, later one of the leaders of the FSM, was arrested in a sit-in at San Francisco’s Palace Hotel (see the sidebar “Mario Savio — An unlikely radical,” later in this chapter).

The demonstrations were successful — the protests resulted in an agreement guaranteeing greater opportunities for blacks. The success of this action created a feeling of euphoria among the protesters, spurring them on to further political activity. They believed that by banding together for a just cause they could accomplish anything.

Exercising freedom of speech

After the HUAC protests and the strikes in San Francisco, the Berkeley administration decided to curtail any political activity that might threaten the business community or jeopardize research money from the military-industrial complex. The hotbed of political activity at Berkeley was Bancroft and Telegraph avenues, where activist groups set up tables and booths to distribute political literature and raise funds. On September 16, 1964, the university banned these tables to stop the messages that it didn’t like.

However, the ban backfired. Students realized that the right to make their political views known wasn’t only a left-wing issue; it was also in accord with their First Amendment rights. Diverse student groups rallied to protest the ban, and even some conservative students joined in the fight. Throughout most of the month, students unsuccessfully tried to negotiate with the administration, but by September 29, students decided to take direct action.

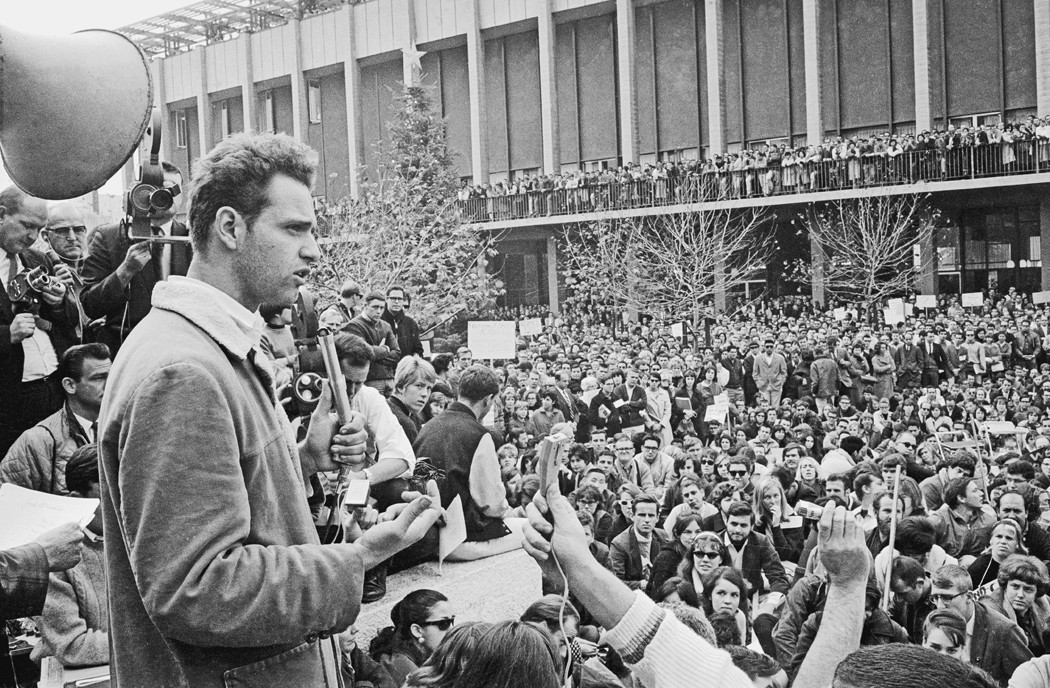

The first mode of attack was civil disobedience. Students continued to set up the tables and distribute literature. When the police ordered the students who were working the tables to leave, other students replaced them. Eventually, on October 1, the university suspended the demonstration leaders and had them arrested. These suspensions and arrests infuriated the students, who surrounded the police cars and began demonstrations at Sproul Hall. One student sat in an immobilized police car for 32 hours — and Mario Savio stood on this car to make his famous speech (see Figure 11-1 and refer to the sidebar “Mario Savio — An unlikely radical” in this chapter).

On October 5, the continuing protests were seriously impairing the university, so they agreed to appoint a committee of students, faculty, and administrators to deal with the issues. As a result, the students agreed to stop demonstrating, and the administration appointed a committee to re-examine the rules. However, when the committee recommended reinstatement for the suspended students, the administration refused, and the students again demonstrated at Sproul.

No matter what the administration agreed to, its main goal was to break up the student coalition. The administration decided that students could have their tables back but couldn’t advocate unlawful activity. Sounds reasonable, right? The catch was the contention that because the civil rights advocates and other left-wing groups encouraged civil disobedience, they were promoting unlawful activity.

The sit-in at Sproul

The administration at Berkeley refused to reconsider its position on the student suspensions (see the preceding section) or on political activity, so once again led by Mario Savio, the students had a massive sit-in in and around Sproul Hall, the university’s administrative center, on December 2, 1964. Students made themselves comfortable in the hall — it was almost like a dormitory, with people playing music, dancing, studying, or just talking. Chancellor Edward Strong ordered the students to leave the building at 3 a.m., threatening police action if they refused. However, all that happened was that police surrounded the building and allowed people to leave, but they didn’t let anyone enter. People who wanted in were so determined that they climbed up ropes to get in through the windows.

Governor Pat Brown ordered the students to withdraw, and on December 3, 600 campus and Berkeley police officers, deputy sheriffs, and highway patrolmen started clearing the hall, carrying students out. Many refused to leave, and leaders of the sit-in began to demonstrate how to resist by making their bodies go limp when the police tried to drag them out. Ultimately, the police arrested and carried out 814 students to end the sit-in. However, the protests continued as Savio called for a general strike, which virtually disabled the campus (see Figure 11-1).

|

Figure 11-1: Mario Savio rouses the free speech demonstrators. |

|

©Bettmann/CORBIS

Joan Baez — The voice of free speech

Joan Baez loved to sing and write folk songs (see Chapter 15), but she was equally committed to social change. Since the beginning of her career, her music reflected her concern with civil rights, equality for workers, freedom of speech and expression, and opposition to an unjust war. In 1964, she withheld 60 percent of her income tax from the Internal Revenue Service to protest military spending. Baez participated in the birth of the free speech movement at UC Berkeley and sang at several of the protests, including Stop the Draft Week in Oakland, where she was arrested (see Chapter 9 for more about Stop the Draft Week).

After the arrests, the administration had a meeting to explain its position, but the meeting only made matters worse. Savio asked to speak at the meeting, but the administration refused. Savio shouted out anyway, turning the meeting into a complete free-for-all. In the end, the students considered their FSM a victory when, on December 8, the Academic Senate (a body consisting of members of the administration and faculty responsible for managing faculty, curriculum, and admissions issues) passed a resolution that reversed student suspensions and limited the administration’s power over political activity on campus. Yet the student protests at Berkeley were far from over as new issues gathered students’ attentions — by this time Vietnam began to occupy student thoughts and efforts.

Mario Savio — An unlikely radical

Mario Savio was one of the most recognizable leaders of the student protest movement. He was, in a way, an unlikely radical, a young Catholic altar boy from a working-class family in Queens, New York. Savio’s activism began during the summer of 1964, when he joined the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) to register black voters in Mississippi. However, later that year, on the Berkeley campus, he became a true activist leader, inspiring students and faculty to join the free speech movement (FSM). He became a media darling when his picture, standing on top of a police car and addressing thousands of students, hit the newspapers and the small screen.

Savio wasn’t only charismatic, he was poetic. In his speech before the takeover of Sproul Hall (check out “The sit-in at Sproul” in this chapter for more), he said, “There is a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart that you can’t take part, you can’t even tacitly take part, and you’ve got to put your bodies upon the gears, and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the appara- tus. And you’ve got to make it stop.” These were certainly Savio’s most famous words and were a rallying cry for the FSM and for activism as a whole.

Savio risked his academic career, as well as his personal freedom, to participate in the marches, sit-ins, and other demonstrations — he spent four months in jail for supporting free speech and the right to demonstrate and protest. After the FSM ran its course, Savio led a quiet life and limited his activism to working against Proposition 187 in 1994, which cut off some health and social services and access to public education to illegal aliens and their children, and Proposition 209 in 1996, which was designed to undermine affirmative action on state campuses.

Berkeley meets the Haight

While Berkeley students were true political activists, the counterculture was alive and well on the other side of the bay, in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Although they were against the Vietnam War and for civil rights, hippies were more interested in free love and drugs and a life free of materialism and middle-class values (for more about the hippies, see Chapter 14).

The hippies were against the war, but they disagreed with the Berkeley students about how to stop the war. They believed that music, love, “flower power,” and a little bit of weed would stop the war, while the Berkeley protesters believed in strikes, sit-ins, and demonstrations. However, as the ’60s progressed, the groups drew closer together — the end was more important than the means, and the hippies joined with antiwar groups from all over the country to protest at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago (see Chapter 9).

. . . and Oakland

Just as with the San Francisco strikes to end hiring discrimination, the students’ concerns went beyond the Berkeley city limits. The Vietnam War brought the protesters into Oakland. In May 1965, antiwar protesters formed the Vietnam Day Committee (VDC) to bring attention to what the United States was doing in Vietnam. Protesters decided to march to the Oakland army terminal to stop the trains taking soldiers on the first leg of their journey to Vietnam. The city of Oakland refused to give them a permit, but the VDC decided to hold the march anyway.

In October 1967, Berkeley again met Oakland during Stop the Draft Week, a nationwide effort to protest the continuing war in Vietnam (see Chapter 9). On October 16, Stop the Draft Week organizers led 3,000 protesters to the Oakland Induction Center to try to prevent new recruits from entering the building. Police formed a human barricade to enable inductees to pass and then arrested the demonstrators. However, the results were mostly symbolic. Protesters didn’t stop one inductee from going to Vietnam.

At this point, the FSM went from protest to active resistance, because their protests hadn’t had much effect — the war just kept escalating. Because the protesters had become more alienated from society as a whole, they were willing to be more militant. One of their objectives was to raise the cost of the war on the home front by creating civil unrest. Their position was that if the war continued, they would cause chaos in the streets at home.

People’s Park

Despite the long-standing conflict between the administration and students at UC Berkeley, a dirt parking lot at Telegraph Avenue and Haste Street finally created an all-out war.

Turning a parking lot into paradise

Originally, People’s Park was a piece of property that the university bought in 1968 in order to build new dorms. The university demolished some dilapidated houses that were there, but the dorms were never built. By sheer coincidence (accidentally on purpose?) the old wood houses were home to student radicals that were thorns in the administration’s side.

By 1969, the Berkeley community, including UC Berkeley students, decided to make the old parking lot into a community park. Building the park was truly a joint effort by students, hippies, street people, activists, and ordinary citizens. They laid sod, planted trees, and built a playground. It was an ideal example of people working together to create something that could benefit everyone in the community.

No walk in the park

People’s Park remained a controversial and embattled site throughout the years. The fence stayed up until May 1972, when demonstrators, protesting Nixon’s proposed bombing of North Vietnamese ports (see Chapters 3 and 8 for more information about the Vietnam War), ripped it down. In September, the Berkeley City Council voted to lease the site, and People’s Park actually came to be used as it was originally intended — a park for all the people of Berkeley.

However, the fragile armistice didn’t last. In 1991, UC Berkeley was ready to take People’s Park back to build volleyball courts. It seemed like déjà vu — negotiations failed, UC sent in the bull- dozers, and the students and residents protested. Although the university won and built their volleyball courts, they were plagued by constant vandalism. In 1997, the university dismantled the courts, and today, community groups and the university manage People’s Park.

They laid sod, planted trees, and built a playground. It was an ideal example of people working together to create something that could benefit everyone in the community.

Unfortunately, the park didn’t please everyone. The university decided that because it legally owned the land, only it could decide what to do with the land. For about three weeks after the park was finished, the builders negotiated with the university, hopeful that they could reach a settlement that would please everyone. However, the administration abruptly stopped negotiations, sent in the police, and built a fence. Those who built People’s Park were furious. They wondered why the authorities waited until all the hard work was finished before telling them they couldn’t have their park. The battle was on.

Calling out the troops — tragedy strikes

On May 15, Berkeley students quickly organized a rally at Sproul Plaza (in front of Sproul Hall, the university administration building) on the Berkeley campus to protest the fence. When a student leader said, “Let’s go down and take the park,” police turned off the sound system. Then, 6,000 people marched down Telegraph Avenue toward the park, but the police were waiting, armed with rifles and tear gas. Fire hydrants were opened, rocks were thrown, and the day descended into chaos and violence. When sheriffs’ deputies fired into the crowd, about 120 people were hospitalized, and a bystander, James Rector, died of gunshot wounds.

Eventually, supporters of People’s Park were the losers. The day after the shootings, Governor Reagan called out the National Guard and was reported to have said, “If there has to be a bloodbath, then let’s get it over with.” Helicopters sprayed tear gas on the protesters, and the Guard barricaded and occupied the city for several weeks, imposing a curfew and a ban on public assembly at the park. But mass demonstrations continued. Two weeks after the fence went up, a peaceful group of 30,000 marched to the park, but to no avail — the fence stayed up, and for the moment, active rebellion ended.

Participating in Student Society

The main author of the Port Huron Statement was Tom Hayden, a former editor of the student newspaper at the University of Michigan. Like Mario Savio, he was born in a working-class Catholic environment. Hayden spent the greater part of 1961 protesting segregation in the South. Later, inspired by Jack Kerouac’s beat novel On the Road, he hitchhiked across the country and got a firsthand look at was going on at Berkeley.

Hayden, one of the leaders of the New Left, was actively involved in antiwar protests. In 1968, he flew to North Vietnam to protest against the war, and later that year, he was one of the prime movers of the demonstrations at the 1968 Democratic National Convention (see Chapter 9).

Participatory democracy and direct action

SDS grew dramatically, from fewer than a thousand members in 1962 to at least 50,000 in 1968, due mostly to student opposition to the Vietnam War (which involved many people who previously didn’t care about politics). Its largest growth occurred after 1965, when SDS spearheaded an antiwar march on Washington, which attracted more than 15,000. Over the next three years, thousands joined SDS.

In 1968, about 40,000 students on nearly a hundred campuses across the country demonstrated against the Vietnam War and against racism. Protest against one cause often morphed into protest against the other. At Columbia University, an antiracist demonstration developed into a huge protest against the war and military research at the university. Students occupied and barricaded the administration building and other campus buildings and set up “revolutionary communes” behind the barricades. (See Chapter 9 for a detailed look at the antiwar movement.) Again, as happened in Berkeley, official overreaction caused a far greater problem. When the police stormed the buildings and brutalized the occupying students, even the moderate majority of students at Columbia joined a boycott of classes, and eventually shut down the university.

Knowing which way the wind blows — the Weathermen

One of their first major actions was the Days of Rage demonstration in Chicago in October 1969, designed to tear the “pig city” apart. The Weathermen hoped that tens of thousands of people would wage guerilla war in the streets, but fewer than 300 showed up. The demonstrators not only vandalized banks and corporations but also destroyed the property of ordinary working people.

After the Days of Rage, the Weathermen lost any sympathy they had from moderates. They knew that they were acting alone, and that made them even more determined and violent. Although most of them were from comfortable middle-class backgrounds with no knowledge of weapons or violence, they plotted to bomb buildings in major cities and mentally convinced themselves that they could murder in the name of revolution.

Two events transformed the already radical Weathermen into revolutionaries. On December 4, 1969, Chicago police shot to death two Black Panthers, Fred Hampton and Mark Clark. Because the FBI had publicly declared its intention to wipe out the Panthers by the end of the decade, the Weathermen considered that this was the opening act of a war between the government and people of America. These two murders confirmed the Weathermen’s belief that violence was necessary to revolutionize society, and they planned bombings against government targets. In March 1970, a bomb that they were building exploded in a townhouse in New York’s Greenwich Village.

After the explosion, the Weathermen went underground, creating false identities and moving around the country to avoid detection. Although they con- tinued bombing corporate and military targets, the Weathermen did everything possible to avoid death or injury as a result of their bombings by phoning in warnings to evacuate the targeted buildings.

At the height of the Weather Underground, members were determined to abandon all the bourgeoisie standards and comforts. They lived communally, often in old or condemned buildings, opposed monogamy, and experimented with drugs and casual sex.

The Weather Underground was fairly successful at avoiding arrest, but by the late ’70s, the group began dissolving. With the exception of Kathy Boudin (who spent more than 20 years in prison for participating in the 1981 Brinks robbery, during which an employee was killed), most Weathermen who were caught or surrendered rarely served long prison sentences.