Chapter 6

Sitting, Riding, and Marching for Freedom

In This Chapter

Inspiring the movement — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Inspiring the movement — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Refusing to budge at lunch counters

Refusing to budge at lunch counters

Organizing to fight for freedom

Organizing to fight for freedom

Standing firm while traveling south

Standing firm while traveling south

Mixing hope and despair: The events of 1963

Mixing hope and despair: The events of 1963

Targeting Mississippi with Freedom Summer

Targeting Mississippi with Freedom Summer

Legislating equality once again

Legislating equality once again

The civil rights movement wasn’t a single event, but collectively it was one of the most important events of the 1960s and perhaps of the entire 20th century. Seeking to undo the evils of slavery and the injustices of the post–Civil War South, the movement’s initial focus was integration of public facilities. With peaceful protests inciting violent backlashes, coupled with the fact that television brought the movement into the living rooms of America, whites learned about the injustices suffered by black Americans.

In this chapter, we take a look at the civil rights movement during the first few years of the 1960s. During those years, until 1964, the movement was dominated by the nonviolent principles of Martin Luther King Jr., the most famous civil rights leader. You can see how African Americans capitalized on the success of the Montgomery Bus Boycott by conducting sit-ins at lunch counters, carrying out freedom rides to integrate interstate transportation, creating organizations to work for desegregation, challenging segregation in the most segregated states in the nation, and marching on Washington, D.C., to make all Americans aware of the need for integration and civil rights legislation. And you can see some of the movement’s goals realized with passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Preaching Nonviolence: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

|

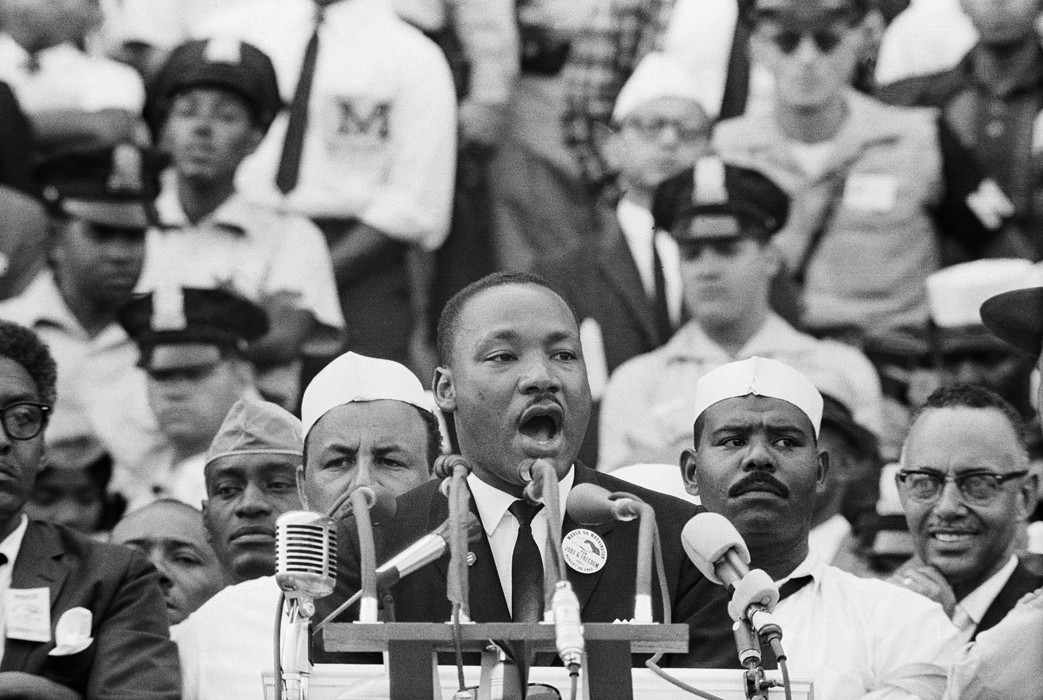

Figure 6-1: Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington. |

|

©Bettmann/CORBIS

Keeping the faith

Throughout King’s public life, his message was always firmly rooted in his deep religious faith, which was only natural because he was the son and grandson of Baptist preachers. An outgrowth of his upbringing was a talent for public speaking. Whether in the religious or the political arena, King was gifted with the ability to inspire people and spur them to action.

Born on January 15, 1929, King grew up and was educated in Atlanta, Georgia, graduating from Morehouse College with a degree in sociology in 1948. Continuing the family tradition, he went on to Crozer Theological Seminary in Upland, Pennsylvania, graduating with a Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1951. He then went on to Boston University, where he received his PhD in systematic theology in 1955.

In February 1948, while he was attending Crozer, King was ordained at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where he became co-pastor with his father. After he received his PhD, he got his first congregation of his own at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama. It was here that he first burst on the national scene as one of the leaders of the Montgomery Bus Boycott (see Chapter 5).

Embracing peaceful protest

Not only was nonviolence in agreement with King’s religious principles, but he also believed that such protests were the strategy that would win the support of white Americans, especially if the protests were met with violence from racists. He was correct: Though widespread support didn’t come quickly, when protests were shown on national television, America saw southern sheriffs greeting peaceful demonstrators with attack dogs and fire hoses. Many Americans saw, for the first time, how blacks were being victimized by the lawmen that were supposed to support the law.

King was instrumental in forming the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which trained people in methods of nonviolent protest. In Greensboro, Atlanta, Birmingham, Selma, and all over the South, King marched with protesters and was arrested time and again for civil disobedience. But King was not the only one to promote the principles of peaceful protest; the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded in 1942, also believed in passive resistance to achieve their goals (see the “Making Alphabet Soup: CORE, SCLC, SNCC, and NAACP” section later in this chapter.)

Gaining worldwide recognition

After his leadership role during the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955 and 1956, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. became nationally recognized as a civil rights leader. Throughout his career, he met with presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson to keep the fight for civil rights legislation at the forefront of their national agendas.

Perhaps King’s most visible moment was the March for Jobs and Freedom in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963, where he gave his famous “I have a dream” speech. This event was organized as much to support the push for civil rights legislation as to protest the segregation and racism that made new legislation necessary. Initially, Kennedy tried to convince King not to hold the march, but he knew that the march would be important to the cause. King’s instincts were correct — the march drew more than 200,000 people, both blacks and whites, and was, up until that time, the most important civil rights demonstration in history. After this march, which was covered on television, the movement gained momentum.

After Kennedy’s assassination, President Johnson fought for passage of the Civil Rights Act. On July 2, 1964, he signed it into law (see “The Civil Rights Act of 1964” section at the end of this chapter), and on August 6, 1965, the Voting Rights Act, which ensured that all citizens would be able to vote, regardless of race, was enacted (see Chapter 7).

In 1963, King was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year,” and on October 14, 1964, he won the Nobel Peace Prize. King turned over the prize money (more than $50,000 at the time) to be used to further the civil rights movement. At age 35, King was the youngest man, the second American, and the third black man to receive the Nobel Peace Prize.

Facing dissension in the ranks

In the late ’60s, King also drew criticism because of his opposition to the Vietnam War. Although he avoided the issue through 1966, he then declared that the United States had been wrong from the beginning of the war and encouraged young men to become conscientious objectors. One consequence of his position was that LBJ, who had supported King and the civil rights movement, felt betrayed. Time magazine (which had earlier named him “Man of the Year”) as well as the Washington Post condemned his position, feeling that he was giving support to the enemy. Interestingly, by 1968, a year after King’s “Beyond Vietnam” speech in 1967 (see Chapter 9), King’s position was the majority, and many Americans no longer supported the war in Vietnam.

Dying young

Ironically for a man who preached nonviolence, King was no stranger to being the target of aggression. During the Montgomery Bus Boycott his house was bombed, and in 1958, while autographing his book Stride Toward Freedom, he was stabbed in the chest. He received many death threats over the years, but he claimed to be unafraid because he felt that personal consequences weren’t that important. Ironically, on the day before he was assassinated, King gave his “I’ve been to the mountaintop” speech, which expressed his thoughts about and foreshadowed his own death.

After President Kennedy’s assassination, King expressed his concern that unfortunately the country’s climate condoned men who expressed their disagreement through violence and murder. At that time, he also said that he believed he’d be assassinated before his 40th birthday. That prophecy proved to be true. On April 4, 1968, while in Memphis, Tennessee, to support a sanitation workers’ strike, James Earl Ray, a high school dropout, petty criminal, and self-proclaimed racist, shot and killed King. At King’s funeral in Atlanta, about 200,000 people marched behind his casket, which was on a sharecropper’s wagon pulled by mules.

The FBI almost immediately identified Ray as King’s assassin and chased him from place to place until they apprehended him in England. He confessed, and in May 1969, was sentenced to 99 years in prison. However, Ray recanted his confession three days later, claiming he was coerced, and put forth a theory that there was a government conspiracy and coverup — an opinion that King’s son, Dexter, as well as Jesse Jackson, support.

In the short term, the aftermath of King’s murder was one he would’ve despised; blacks were so enraged about the assassination that they rioted in protest in 100 cities, and more than 10,000 people were arrested (see Chap- ter 7). However, his long-term legacy highlights the progress of blacks in American life. Public facilities throughout the South were integrated (or at least they weren’t legally separated), and white America began to think about race in a different way. Because of his efforts, which resulted in more black voters, blacks gained a foothold in government: Edward Brooke became a senator from Massachusetts, Thurgood Marshall became a Supreme Court justice, Carl Stokes and Richard Hatcher were big city mayors, and Shirley Chisholm became the first black congresswoman.

A powerful enemy: J. Edgar Hoover

FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and the rest of the FBI were never comfortable with Martin Luther King Jr. To them, nonviolent protest had a suspicious, almost un-American air about it (or about any protest against government, for that matter). Hoover felt that King and the civil rights movement were instigated by Communists and what Hoover called “outside agitators,” who were stirring up discontent among blacks and the poor. Unfortunately, some of King’s supporters had Socialist and Communist ties, which gave the FBI a rationale for pursuing King.

Hoover worked with the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), a committee in the House of Representatives whose mission was to fight Communism wherever they saw it (see Chapter 11) to paint King with a pink paintbrush, but the accusations never stuck. So Hoover went after King personally by delving into his personal life and attempting to blackmail him into stopping his activism. However, none of Hoover’s attempts much affected King’s work or his legacy.

Opening the Lunch Counters: The Sit-In Movement

Although almost all restaurants and lunch counters (casual restaurants where customers were served from behind a counter) in the South were segregated, Woolworth’s was a good choice because it wasn’t just a luncheonette. At the time, it was the largest national five-and-ten-cent store. Woolworth’s always welcomed people of all races to buy cosmetics, toys, and other miscellaneous items in their stores, but in the South, blacks couldn’t eat at Woolworth’s.

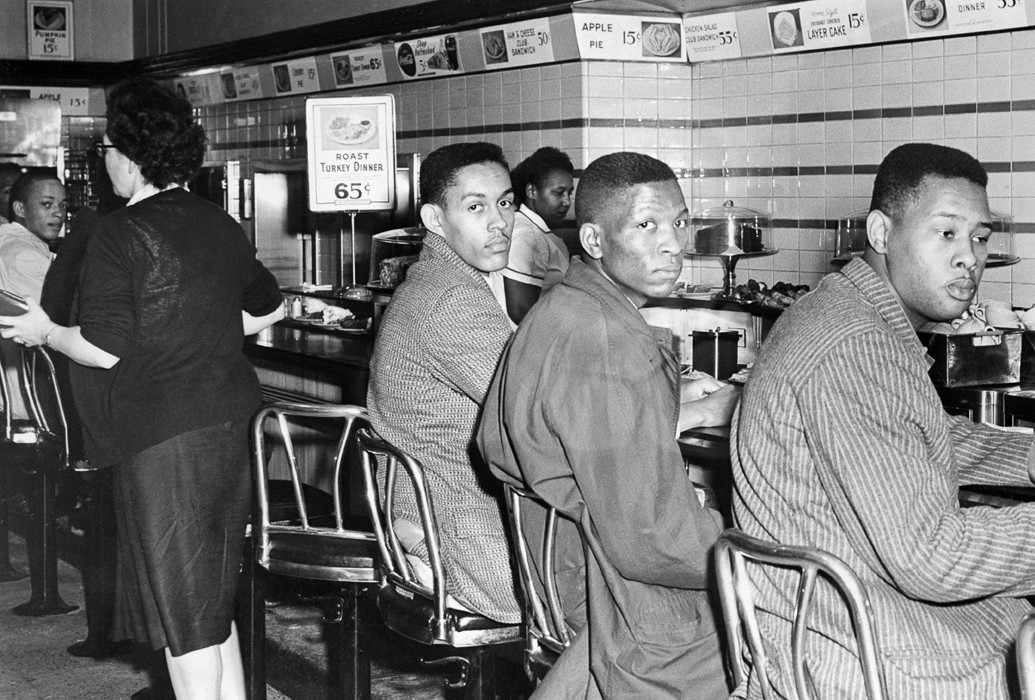

On the first day, nothing much happened — the four students sat at the lunch counter and were never served (they were largely ignored), so they stayed until closing. But the students wanted a reaction and publicity, so they recruited more students to come to Woolworth’s. Throughout the next week, more students continued occupying the Woolworth’s counter until it was so crowded that almost no one else could fit. The results were mixed — the sit-in attracted local reporters, which ensured that they’d receive publicity. However, the manager temporarily closed the store, leaving the students to find another all-white lunch counter to occupy.

|

Figure 6-2: A sit-in at an all-white lunch counter. |

|

©Bettmann/CORBIS

Black students all over North Carolina caught on to the idea, and throughout the next week they held sit-ins in Winston-Salem, Durham, Raleigh, Charlotte, Fayetteville, High Point, Elizabeth City, and Concord. Representatives of CORE went to southern campuses to recruit more students, organize the sit-ins, and teach protesters how to conduct themselves — to always be polite, not disrupt business, and not react to any insults. It didn’t take long for the protests to spread to other states. By the end of February, seven southern states had hosted sit-ins, and by the end of April, almost 50,000 students had participated in sit-ins all over the South.

Northern students, both black and white, supported the southern sit-ins by boycotting chain stores, such as Woolworth’s, that remained segregated in the South. Suddenly, the unfairness became a growing concern. Although the first sit-ins were fairly peaceful, later in February, in Nashville, Tennessee, protesters were attacked by a group of white teens, resulting in the arrest of the black students for disorderly conduct while the white teenagers were released.

Making Alphabet Soup: CORE, SCLC, SNCC, and NAACP

Although they all had the same goals, several important associations were involved in the civil rights movement. These organizations started at different points in the 20th century and didn’t always agree on methods, but in the early to mid-1960s, they worked together to end segregation and ensure that blacks had the right to vote. But there were distinctions between the groups. Some such as the NAACP tended to be more conservative and wanted to work within the system, and on the other end of the spectrum, SNCC preferred a more direct approach, and didn’t particularly worry about white sensibilities. However, they did join together to accomplish common goals, such as the March for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.

The granddaddy of civil rights organizations: The NAACP

Fight Jim Crow (segregationist) Laws such as those that allowed separate public facilities for blacks and whites (see Chapter 5)

Fight Jim Crow (segregationist) Laws such as those that allowed separate public facilities for blacks and whites (see Chapter 5)

Make people aware of the horrors of lynching

Make people aware of the horrors of lynching

Enforce the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees the right to vote

Enforce the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, which guarantees the right to vote

Other important goals were to oppose racist government appointees, such as the nomination of John Parker as a Supreme Court Justice in 1930. Throughout their history, they also spoke out about films that glorified racism, such as Birth of a Nation in 1915, and TV shows that showed derogatory black stereotypes, such as Amos and Andy in 1951.

One of the NAACP’s most important divisions was the Legal Defense and Educational Fund (LDF), founded in 1940. Spearheaded by Thurgood Marshall, who was later appointed to the Supreme Court, the LDF argued school integration cases before the Supreme Court, the most famous and far-reaching of which was the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision, which mandated integration of public schools. (Check out Chapter 5 for a discussion of this decision.) LDF lawyers were also active in other ways:

Activism in the city — the Urban League

In order to improve the conditions of blacks who moved to northern cities in the Great Migration during the late 19th and early 20th century, the Committee on Urban Conditions Among Negroes was established in New York City on September 29, 1910. These new arrivals came north because of bad crops, rampant poverty, and Jim Crow laws, as well as the need for unskilled labor in northern cities and better living conditions. Although there was also poverty and discrimination in northern cities, they still earned more money than they did at home. The organization helped the new arrivals adapt to urban living and overcome poverty and the lack of educational and economic opportunities. By 1920, the committee merged with several other urban organizations to form the National Urban League.

From the beginning, the Urban League was an interracial organization (founded by Ruth Standish Baldwin, the widow of a railroad tycoon and Dr. George Edmund Haynes, the first black man to earn a PhD from Columbia University) that helped blacks gain better access to recreation, housing, healthcare, and education. However, the league’s greatest push was in the area of employment. To create new opportunities for blacks, they boycotted firms that wouldn’t hire them. They also pressed to have blacks included in New Deal programs (government programs designed to provide employment and stimulate economic growth during the Great Depression from 1929 to 1933), and worked to get them admitted into labor unions. Although the league didn’t actively participate in the civil rights protests of the ’60s, it consistently worked behind the scenes to ensure equal opportunities for all Americans, focusing on economic and educational progress.

They defended several civil rights leaders, including Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, and James Meredith when they were arrested during protests.

They defended several civil rights leaders, including Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, and James Meredith when they were arrested during protests.

They pursued employment discrimination cases and pushed for affirmative action.

They pursued employment discrimination cases and pushed for affirmative action.

They defended Rosa Parks after her arrest, and the organization was active in the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955.

They defended Rosa Parks after her arrest, and the organization was active in the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955.

The group was so effective that the state of Alabama prohibited them from operating within the state. (The Supreme Court eventually overturned this state law.)

Bringing whites to the fight: CORE

In 1942, a group of students in Chicago banded together to form the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) to fight segregation and racism by using nonviolent resistance, including sit-ins, jail-ins, and freedom rides. From the beginning, CORE attracted both blacks and whites, and its members were mostly college students. Its first leaders were two University of Chicago students: George Houser, who was white, and James Farmer, who was black.

CORE’s first efforts were sit-ins, conducted to protest segregation in public facilities. Later that year, the organization went national. Farmer, along with Bayard Rustin, traveled around the country recruiting new members. By the end of the 1940s, CORE was successful at integrating public facilities throughout the northern states.

Although CORE kept working to end segregation, by the late ’50s the organization was stagnating. However, with the Montgomery Bus Boycott, which used the nonviolent methods that CORE advocated, the organization was again in the forefront of the civil rights movement. CORE participated in the lunch counter sit-ins, freedom rides, and voter registration drives. But by the late ’60s, CORE was again in crisis. Although they still advocated interracial membership, some black members didn’t want to be restricted to nonviolent methods of protest. In 1966, Farmer stepped down as leader, and when Floyd McKissick, who embraced the concept of black power, took over the organization, it became more militant. Although not advocating violence, it was accepted if nonviolent methods weren’t successful.

Fighting with faith: The SCLC

Although the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) didn’t become an official organization until 1957, its roots were in the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955 and 1956 (see Chapter 5). The boycott, a huge and successful nonviolent protest, was organized and executed by the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), led by Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy.

Unsung heroes of the movement

One of the oldest civil rights leaders was A. Philip Randolph, who formed the first black labor union in 1925, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Throughout his life, Randolph worked to help the black working class and was also instrumental in the fight to end segregation in the military. Randolph was one of the organizers of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.

Bayard Rustin was an active member of CORE and one of the founders of SCLC. Born a Quaker, he was a committed pacifist who believed in nonviolent protest. Although he actively worked in the civil rights movement, he was forced to work in the background because he was gay, and no one wanted his sexual orientation to discredit the movement. However, later in life, he openly worked to promote gay rights.

Another SCLC leader who had a huge impact on the civil rights movement was Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth. One of the leaders of the 1963 demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama, he was arrested and jailed along with Dr. King. Although he was injured and hospitalized during the worst moments of the protests, he convinced King to keep on, regardless of police resistance.

After the boycott ended, the MIA and other protest groups met to form an organization to coordinate peaceful protests throughout the South. During a meeting in Atlanta in January 1957, King, Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, and Bayard Rustin (of CORE) officially formed the SCLC. The new organization’s initial announcement stated that civil rights were essential to democracy and that segregation must end. They pledged that the SCLC would be open to anyone regardless of race, religion, and background. Rather than seek individual members, the SCLC coordinated local civil rights organizations throughout the South. They also committed to nonviolent protest as their primary strategy and taught their members how to passively resist arrest and violence with the least injury to themselves.

Throughout the ’60s, the SCLC was at the forefront of the civil rights protests throughout the South, participating in the protests in Birmingham in 1963, Freedom Summer in 1964, and the Selma to Montgomery march in 1965. The SCLC was also instrumental in organizing the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.

Although the SCLC lost some of its influence during the late ’60s as the civil rights movement became more militant, it still exists today, working to end discrimination, promote voter education and registration, and advocate nonviolent conflict resolution.

Fighting violently: The Deacons for Defense

During CORE’s 1964 campaign to desegregate public facilities in Jonesboro, Louisiana, local black men began to guard the CORE activists. They decided to form an armed defense group, called the Deacons for Defense, in order to protect civil rights activists from white supremacists. This working-class organization was unwilling to wait for an end to the injustices of racism and instead wanted to defend themselves, especially against the Ku Klux Klan.

In Bogalusa, Louisiana, in 1964, the Deacons armed themselves against Ku Klux Klan violence, which provoked more terrorism against blacks, including the murder of a white policeman. Eventually, the federal government intervened, compelling the local government to abide by the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, in the process the Deacons attracted the FBI’s attention, which called them a dangerous black group.

By 1966, the Deacons became embroiled in the rifts that were forming in the civil rights movement. After James Meredith was shot and wounded, the NAACP, SCLC, and the Urban League still wanted to continue nonviolent, interracial protest, while CORE and SNCC wanted to restrict the demonstration to blacks and invited the Deacons for Defense to protect the marchers. Although they faded from the scene by 1972, the Deacons were a large part of the shift from nonviolent protest to black militancy.

Mobilizing students: The SNCC

Two months after the first lunch counter sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina, students in Raleigh formed the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC; usually pronounced snick ) with the objective of coordinating, supporting, and publicizing the sit-ins.

Throughout the rest of the decade, however, SNCC, along with the rest of the civil rights movement, widened its focus to fight all racial oppression in any form. With its youthful, interracial membership, SNCC actually overshadowed some of the more established civil rights organizations, such as the NAACP and SCLC, during the late ’60s. They were a major participant in the freedom rides, the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, Mississippi Freedom Summer, and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which focused on education and voting rights for blacks.

However, over the next few years, many SNCC activists began to lose patience with nonviolent protest and civil rights legislation and believed that equal rights could only be achieved by more direct and militant means. In May 1966, Stokely Carmichael became the leader of the organization. At first, he said that blacks should be able to use violence in self-defense, but later he began advocating the initiation of violence in order to fight oppression. Under his leadership, SNCC got rid of the organization’s white members. In June 1967, Carmichael left SNCC to join the Black Panther Party (see Chapter 7). Although SNCC renounced the philosophy of nonviolence in the late ’60s, Martin Luther King Jr. and the SCLC originally supported the student organization.

Going on a Road Trip: Freedom Rides

The first freedom ride of the decade began on May 4, 1961, when the Supreme Court extended its desegregation of interstate travel beyond the actual buses to bus terminals as well. A group of 13 students, black and white, left Washington, D.C., in two buses, a Trailways bus and a Greyhound bus, headed for New Orleans. The group made it through Virginia and North Carolina without incident, but at the Greyhound depot in Rock Hill, South Carolina, a mob attacked the group as they entered the white waiting room. Police intervened, and the group was admitted to the waiting room.

The trip through Georgia was uneventful, but the Greyhound bus was stopped in Alabama when a mob surrounded the bus, slashed the tires, and set the bus on fire. Not discouraged, the ride continued. However, in Anniston, Alabama, one bus driver wouldn’t move the bus until the group segregated itself, and the other bus was burned (but the riders caught another bus and continued on.) They finally headed to Birmingham, where more violence waited for them, hospitalizing some of the riders. After that, they found no bus that would take the integrated group. The first freedom ride of the ’60s was over. Figure 6-3 shows the freedom riders and their burnt-out bus.

|

Figure 6-3: Freedom riders watch a bus that was set on fire in Anniston, Alabama. |

|

©Bettmann/CORBIS

Although the first freedom ride didn’t reach its destination, the riders vowed to continue and organized a ride from Nashville, Tennessee, through Montgomery and Birmingham, and on to Mississippi. They made it as far as Birmingham, where they were jailed and run out of town by Police Chief “Bull” Connor (more about him in the section “The Battle of Birmingham,” later in this chapter). President Kennedy worried about violence against the freedom riders and insisted that the governor of Alabama guarantee their safety. However, a mob was waiting in Montgomery, and along with the students, newsmen and cameramen were beaten in a riot that went on until police used tear gas to disperse the crowd (which had grown with onlookers and supporters for both sides in the melee). Undeterred, the group rode on to Jackson, Mississippi, where they were arrested for using white restrooms and waiting rooms. They spent the night in jail.

For the freedom riders, the violence and arrests just seemed to strengthen their resolve. The mob violence that the rides provoked served to gather support from northern blacks and many whites as well.

Shaking the Nation: Turning Points in 1963

The year 1963 was pivotal for the movement. In Birmingham, Alabama, police violently opposed peaceful protest, and later that year, segregationists bombed a Birmingham church, killing four black girls. In Mississippi, civil rights worker Medgar Evers was murdered in cold blood. On a more hopeful and optimistic note, civil rights organizations banded together and organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, designed to promote equal opportunity, end segregation, and support passage of civil rights legislation.

The events in Alabama and Mississippi turned many people, who were previously unaware of the evils of segregation and the intensity of racism, in favor of the civil rights movement, and the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom emphasized the massive support for civil rights at all levels of American society.

The Battle of Birmingham

In the beginning of 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and other black leaders decided to concentrate their efforts on what they considered to be one of the most segregated large cities in the United States — Birmingham, Alabama. However, no one thought it would be easy — George Wallace had just been elected governor on a segregationist platform and was determined not to let the protesters take over his city (for more on George Wallace, see Chapter 13). In addition, the Birmingham Ku Klux Klan was supposedly one of the most violent chapters in the country, so the demonstrators had their work (and their strength of will) cut out for them.

Ralph Abernathy and King went to downtown Birmingham on April 12 and were arrested for defying Police Chief Bull Connor’s order prohibiting demonstrations. When protestors staged a large demonstration, Connor, in a show of force, set vicious police dogs on the protestors, turned the fire hoses on them, and had them beaten with clubs. Some historians speculate that Connor’s overt racism and brutality prompted so much outrage that it hastened the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

After King was released from jail on April 20, SCLC began planning the next phase of the demonstration. On May 2, a large group of children joined the protest. The plan was to attract the media and embarrass the city of Birmingham. After King gave a speech at the 16th Street Baptist Church, the march moved downtown, but Connor and his policemen were waiting, and they arrested more than 900 youngsters. The next day, approximately 1,000 more children more joined the march, but this time Connor didn’t stop at mere arrests.

The police attacked the marchers — which included all those children — with fire hoses, clubs, and attack dogs. Thanks to the media, Americans all over the country saw youngsters being savagely beaten, but Connor wouldn’t be stopped. The following day, Connor again ordered an attack, but because of the number of young children involved, firemen refused to turn on the hoses, and many of the police wouldn’t participate in the violence. This time, Connor had to settle for making arrests.

Finally, on May 10, the city of Birmingham responded to pressure from the federal government and the weight of world opinion (as well as the fact that they had no more room in the jails) and agreed to desegregate. However, the Ku Klux Klan and other white segregationists were furious and went on a rampage, rioting throughout the city and bombing black churches, businesses, and homes. King’s brother’s home, the motel where King was staying, and the SCLC headquarters were among the buildings destroyed.

The murder of Medgar Evers

Medgar Evers was a Mississippi native who worked for civil rights and paid for them with his life. After graduating from Alcorn State College in Lorma, Mississippi, he applied for admission to the segregated University of Mississippi Law School, but his application was rejected. This caused the NAACP to become involved in the desegregation efforts at Ole Miss, and although Evers never gained admittance, he was instrumental in getting James Meredith admitted in 1962.

Although his first post-graduation job was selling insurance, Evers’s real passion was to improve the lot of poor black families in Mississippi. In 1954, he joined the NAACP and became Mississippi’s first field officer, responsible for forming local chapters and organizing desegregation efforts throughout the state. In this position, he fought to enforce the desegregation mandated by Brown v. Topeka Board of Education (see Chapter 5). He also pressed for enforcement of black voting rights and encouraged blacks to boycott merchants who discriminated against them. Evers’s activism provoked death threats, but he wouldn’t be deterred from his work. However, on June 13, 1963, he was shot in the back when he got out of his car.

Police had no problem finding the culprit, because the shotgun that killed Evers (complete with fresh fingerprints) was found in the bushes; Byron de la Beckwith, owner of said fingerprints and an active white supremacist, was arrested. Although the prosecution submitted hard evidence against him, including the fact that he publicly stated that he wanted to kill Evers, two all-white juries deadlocked, and Beckwith seemingly got away with murder. However, in 1989, new information indicating that the juries may have been tampered with prompted a new trial. On February 5, 1994, a jury of blacks and whites found Beckwith guilty, sentencing him to life imprisonment.

The March for Jobs and Freedom

As protests intensified, President Kennedy realized that without an effective civil rights law, desegregation wouldn’t occur “with all deliberate speed.” As far as black Americans were concerned, the nation’s response to Brown v. Topeka Board of Education, which declared that “separate but equal” facilities were unconstitutional, was agonizingly slow, and neither state legislatures nor Congress seemed willing to press for enforcement. Finally, on June 11, 1963, Kennedy proposed a bill that would ensure equal protection under the law for all Americans.

To publicize the bill and support its passage, A. Philip Randolph (see the sidebar “Unsung heroes of the movement”) called for a massive march on Washington for jobs and freedom, inviting people and groups of all races and religious persuasions to participate. Passing a civil rights bill was so important that all civil rights groups, including the NAACP, CORE, SCLC, SNCC, and the Urban League, joined together to organize the march. (Malcolm X and the Black Muslims opposed the march, calling it the “farce on Washington.”) Although the main objective of the march was the passage for civil rights legislation, other goals were to

Eliminate segregation in schools and other public facilities

Eliminate segregation in schools and other public facilities

Protect protesters from police brutality and vigilante justice

Protect protesters from police brutality and vigilante justice

Implement a public-works program to provide jobs

Implement a public-works program to provide jobs

Prohibit discrimination in hiring

Prohibit discrimination in hiring

Raise the minimum wage

Raise the minimum wage

Establish self-government for the District of Columbia, which had a black majority

Establish self-government for the District of Columbia, which had a black majority

Although President Kennedy introduced the Civil Rights Bill, he originally opposed the march, because he was worried that a white backlash might actually strengthen resistance to civil rights legislation. However, after he realized that the march would go on with or without his backing, he supported the effort.

On August 28, 1963, more than 250,000 people (approximately one-fifth of them white) united in Washington for the March for Jobs and Freedom (see Figure 6-4). Not only civil rights leaders but also clergymen, union leaders, and entertainers such as Sidney Poitier; Marlon Brando; Marian Anderson; Joan Baez; Bob Dylan; Mahalia Jackson; Peter, Paul, and Mary; and Josh White joined the demonstration and entertained and addressed the crowd.

The murder of four girls in a Birmingham church

Unfortunately, despite King’s inspiring words and the hope and enthusiasm created by the March for Jobs and Freedom, in September, one of the worst acts of violence occurred during Sunday services in a black church in Birmingham.

|

Figure 6-4: The March for Jobs and Freedom. |

|

©Flip Schulke/CORBIS

Angered over a federal court order mandating desegregation of Birmingham public schools (and encouraged by Governor George Wallace’s defiance of the order; see Chapter 13), segregationists bombed several places in Birmingham over the next several months. Bombing seemed to be the violence of choice in Birmingham — between 1947 and 1955, more than 50 bombings occurred, earning the city the nickname “Bombingham.”

However, the worst of these attacks was the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, killing four young girls — Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Cynthia Wesley, and Addie Mae Collins — who were preparing for Sunday school in the church basement. The angry black community rioted in protest (in spite of King’s plea for nonviolence), and the authorities retaliated with their usual tactics — attack dogs, fire hoses, beatings, and arrests, but in the end, the bombing strengthened the resolve of civil rights protesters.

King led the eulogy for three of the four girls, and the horrible death of innocent children even prompted many of the whites of Birmingham to attend the memorials. National outrage prompted the FBI to investigate the bombing, particularly because the Birmingham authorities showed little enthusiasm for prosecuting the offenders, even though they knew who the perpetrators were. Based on their findings, the FBI office recommended that the suspects be pros- ecuted, but the FBI leader J. Edgar Hoover wouldn’t allow evidence to go to the federal prosecutor, and in 1968, the FBI closed the case. Not until 1977 was one of the bombers convicted. The other two were finally convicted in 2000.

Heating It Up: Freedom Summer

For many blacks, the desegregation of schools and other public facilities was an important goal, but equally important was the enforcement of the right to vote for all Americans. Many white southerners, afraid that the large black populations would overturn Jim Crow Laws if they were allowed to vote, put up impossible roadblocks. Poll taxes (an amount that had to be paid before an individual could vote) and literacy tests virtually prohibited blacks from voting, although technically their right to vote, guaranteed by the 15th Amendment, was legally enforced.

To prepare for their summer in Mississippi, volunteers (the majority of whom were white middle-class students) attended an orientation, where they were coached on some of the problems they might face, such as arrest, jail, or even death. Freedom Summer volunteers were required to bring $500 for bail money.

Continuing drives to get out the vote

Since the 1950s the NAACP (and later SCLC and SNCC) had organized registration drives in the South to help blacks to register to vote. However, because of literacy tests, poll taxes, and outright intimidation by whites, these drives had limited success. Then, in 1962, an organization of civil rights groups, the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), was established. In 1963, COFO staged the Freedom Vote, a mock election in Mississippi designed to demonstrate that blacks wanted to vote and would cast their ballots if allowed. (White segregationists in Mississippi tried to justify preventing blacks from voting by stating that they really didn’t want to vote anyway.) The Freedom Vote began by holding a mock convention to select candidates for state office, and aided by volunteers, blacks registered to vote. On Freedom Vote’s Election Day, almost 80,000 blacks cast their ballots for the integrated ticket.

SNCC organized Freedom Summer of 1964 to take advantage of the momentum and enthusiasm created by the Freedom Vote. However, some dissention filled the air while the event was in the works — some black leaders feared that white volunteers would take over the movement. Others were concerned about the possible violence that would meet the racially mixed group of volunteers. (In later years, SNCC and CORE became all-black organizations. See Chapter 7 for more information about the segregation of the civil rights movement.)

Providing competition with an alternate Democratic Party

One of Freedom Summer’s objectives was to challenge the regular Democratic Party of Mississippi. To do so, they established the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) to win seats at the 1964 Democratic National Convention.

Although the MFDP candidates lost their bid to become delegates to the convention, they sent a delegation to Atlantic City anyway and presented their credentials. This initiative was a problem for President Johnson, who was up for re-election on a Democratic platform and was trying to maintain the support he’d gained by supporting civil rights legislation without completely losing the Southern Democrats, many of whom were committed to maintaining white supremacy.

Needing to diffuse the racial tensions at the convention, Johnson and his supporters offered a compromise, which would give the MFDP two nonvoting seats. However, MFDP refused the offer and kept up the defiance throughout the convention, trying a variety of tactics to get seated on the convention floor, including borrowing badges and occupying empty seats. After the 1964 convention, discouraged about working in the mainstream Democratic Party, the MFDP became more radical. They invited Malcolm X (see Chapter 7) to speak at their next convention and opposed Johnson’s policy in Vietnam.

In the 1964 presidential election, Johnson took a hit, as white Mississippi Democrats took a position that rejected the national Democratic Party’s civil rights platform, which pledged to end segregation and enforce voting rights and openly supported Barry Goldwater, the Republican candidate who supported states’ rights and opposed civil rights legislation.

Learning equality in Freedom Schools

During Freedom Summer, volunteers established the Freedom Schools, which more than 3,000 students attended in towns throughout Mississippi. Although most of the students were teenagers, some of them were also children who hadn’t yet started school. Besides teaching traditional subjects such as remedial reading and math, one goal of the Freedom Schools was to create a curriculum that was relevant for their students and would also prepare them for becoming equal voting citizens in the future. Therefore, the Freedom School curriculum included black history and the philosophy of the civil rights movement. Essentially, the Freedom Schools were the youth division of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party.

Coping with three Klan murders

As volunteers learned during orientation, participating in Freedom Summer was risky business. White supremacists actively opposed the volunteers, bombing and setting fire to black churches, schools, and businesses. Volunteers, both black and white, were routinely arrested, and many were beaten by segregationist mobs or racist police officers. (One of the things that infuriated the segregationists was the sight of blacks and whites together.)

However, the murder of three civil rights workers was the most blatant act of violence of the summer of 1964. On June 21, James Chaney, a local black volunteer, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, two northern white students, went to investigate a church bombing near Philadelphia, Mississippi. Stopped and arrested for traffic violations, they spent several hours in jail. When they were released later that day, it was the last time anyone saw the three young men alive. Even after they were reported as missing, local authorities ignored the disappearance, stating that they staged their own disappearance to gain publicity for the movement.

The next day, the FBI got involved in searching for the three young men, but their bodies weren’t found until six weeks later. Chaney died as a result of a brutal beating, and Goodman and Schwerner each died from a single gunshot to the chest. On October 13, the FBI arrested 18 men, but state prosecutors, citing lack of evidence, refused to take the case. Therefore, the federal government was forced to charge the suspects with federal conspiracy and civil rights violations. At trial, seven men were convicted, seven were acquitted, and three received mistrials. The longest sentence for the three murders was a mere six years.

Testimony indicated that the Neshoba County police, who had earlier arrested the three volunteers, alerted the local Ku Klux Klan when the men were released from jail. Samuel Bowers, Imperial Wizard of Mississippi’s Ku Klux Klan, was found guilty of giving the order to kill Schwerner. However, years later, he admitted that he covered up the fact that Ray Killen, a Baptist minister and Klan organizer, was the main conspirator in the murders (and said that he was proud of giving the testimony that allowed Killen to go free). In 1998, Bowers was sentenced to life in prison for the 1966 murder of NAACP leader Vernon Dahmer. And in 2005, a Mississippi jury found Killen guilty on three counts of manslaughter for the 41-year-old crime.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 took aim at discrimination and segregation throughout society:

Voting: It mandated equal voter registration.

Voting: It mandated equal voter registration.

Public accommodations: It prohibited discrimination in any public accommodations engaged in interstate commerce (which included not only transportation but also hotels, motels, restaurants, theaters, and so on). This effectively made all Jim Crow Laws, which supported segregation, illegal.

Public accommodations: It prohibited discrimination in any public accommodations engaged in interstate commerce (which included not only transportation but also hotels, motels, restaurants, theaters, and so on). This effectively made all Jim Crow Laws, which supported segregation, illegal.

Public schools: It enforced the desegregation of public schools.

Public schools: It enforced the desegregation of public schools.

Federally funded programs: It authorized the withdrawal of federal funds from programs that practiced discrimination. For example, no segregated school would receive federal funding.

Federally funded programs: It authorized the withdrawal of federal funds from programs that practiced discrimination. For example, no segregated school would receive federal funding.

Employment: It outlawed discrimination in employment based on race, national origin, sex, or religion and included the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to enforce this provision.

Employment: It outlawed discrimination in employment based on race, national origin, sex, or religion and included the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission to enforce this provision.