Appendix B

On the Differences between the Cells of the Higher Plants and the Higher Animals

It is probable that in certain points the cells of the higher animals and the higher plants are not strictly homologous with each other.

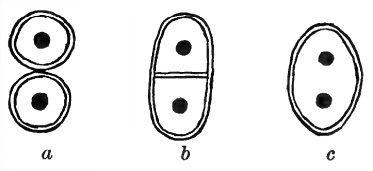

Botanists distinguish three main types of elementary structure among plants, their differences arising out of differences in the method of cell-division practised (Fig. 16). In the first type (Coccoid), the entire cell, with its cell-wall, divides into two similar and quite separate halves. This is practised, e.g., by unicellular Algae. In the second type (Filamentous), the cell-body (cytoplasm and nucleus) divides as before, but the cell-wall does not divide; instead, an entirely new party-wall is laid down between the two cell-bodies, and in this partition small apertures are left, through which the two cell-bodies enjoy protoplasmic communication. This type of organization is found in all the higher green plants. In the third type (Coenocytic) the nucleus alone divides, and the final result is a coenocyte—a single overgrown cell with a single cell-wall and many nuclei. This plan has been adopted by the Siphoneae (pp. 67–68).

It is obvious that the first method is the most primitive and will be most generally practised by unicellular organisms; but whereas it has been abandoned by the higher plants, it seems to have been retained by the higher animals. Almost the only difference between the division of a protozoan and a metazoan cell lies in the fact that the two daughter-cells separate in the one case, cohere in the other. The essential separateness of the cohering cells is well seen in the collar-cells of simple Calcareous Sponges like Clathrina; here indeed there is even no continuity of coherence during normal life (pp. 70–71).

Figure 16

Diagram to show the three main types of elementary structure found in plants. (a) coccoid, (b) filamentous, (c) coenocytic. In each case is shown the sum of the changes following upon binary division of the nucleus of a single cell.

Similar if less strikingly separate cells can be seen in many other groups of multicellular animals, and there can be very little doubt that the first method of division was employed by the common ancestor of all Metazoa;1 true party-walls like those of filamentous plants do not exist in animals, and animal syncytia (tissues formed by the coenocytic method) are undoubtedly secondary.

We must now try and see what these facts mean. In the filamentous type the units are still homologous, as units, with the original units we called cells (p. 43); but they have sacrificed a considerable amount of independence. The whole mode of division by which they arise is an obvious adaptation to a state of existence where each is to be part of a continuous whole.

In Metazoa the separation of the cells is as a rule total, and if protoplasmic continuity exists, it appears to be secondarily produced. As regards their mode of cell-division, therefore, the Metazoa are more primitive than the Metaphyta; yet in spite of—or perhaps because of—this very separateness of their units, there has been a much greater division of labour between different kinds of units in animals than in plants.

To sum up: the cells of the higher plants and of the higher animals are both true cells—they are both broadly homologous with the original units of living matter. But the mode of cell-division in the two groups, in so far as it concerns the separation of the cells and the formation of the boundary between them, is not homologous.