I Think I Could Do This

Because gondolas, to any of us who have lived in Venice for decades, are as common as yellow taxis to a New Yorker, we almost cease to notice them, and thus we seldom give them conscious thought. We passively observe that all other boats defer to them and give them right of way, and the shout of the gondolieri approaching a turn is part of the background noise of the city. If we use them at all, it is as a convenient traghetto service to cross the Grand Canal when we are in a hurry or burdened with produce from the Rialto Market. Thus it was only by force of coincidence that they their familiar invisibility entered my conscious mind, aroused my curiosity and, after some time, led to this book and disc.

About nine years ago, an American friend was given as a Christmas present – I believe it was meant to be a joke – the blueprints of a gondola, complete with detailed instructions. He opened the plans and began to spread them out on the dinner table. As he unfolded the paper, more and more bottles, plates, and cutlery had to be removed to the sideboard or taken back into the kitchen. The paper expanded. When the sides of the blueprint were hanging over the four sides of the table, he turned from them and began to read the instructions that accompanied them.

The other guests at the dinner were forced to balance their plates on their knees or abandon the idea of food altogether and content themselves with wine and conversation. If it is possible to ignore a person looming over a two-meter long blueprint, muttering to himself, then we ignored him. Until suddenly he said, his face alight with a vision of the finished gondola, “I think I could do this.”

The other revelation also came at dinner, as is so often the case in Italy, though this was in a different part of the city and with different guests. A friend lives on the Grand Canal, which means glory and beauty and bliss and endless delight. It also means, alas, gondola-loads of tourists back and forth under the windows, and since these are the gondolas working with large groups of tourists, an accordionist and a singer are tossed in. (Oh, how tempting is that phrase.)

As we ate our risotto, we heard the – dare I use this word? – music approaching. The accordionist squeezed out some notes, and the voice of what I had once heard my Irish grandmother call “a whisky tenor” rose up to the mezzanine apartment, and the words of “O sole mio,” flew up to scandalize us all.

At that point, the host’s dachshund, Artù, leaped up (well, he struggled up because he was a dachshund) onto the wide windowsill, pitched his head back, and began to howl like what that same grandmother would call a banshee. Beside himself, either with the pain caused by the music – pain which we shared – or perhaps deluding himself that this noise came from his dog pack and he was being called upon to declare his solidarity with them, Artù howled his head off whilst the boatloads of tourists below snapped photographs and waved up at him. During this, the gondolier, not the tenor, shouted up, “Ciao, Artù. Che togo che ti xe.” I have many friends who are singers: none of them has ever had a gondoliere call up to tell him what a wonderful singer he is, nor has any one of them been photographed, head back and howling, by boatloads of Japanese tourists.

Let me leave Artù to his art and return my attention to the Master Builder. Construction began, not in Venice but about an hour from the city, where my American friend had access to a complete carpenter’s workshop with ample space to work on the boat. No, he is not a professional carpenter, though he has for years built cabinets, tables, doors, even an elaborate drop-front writing desk. But not, until then, had he thought of building a gondola. Alone.

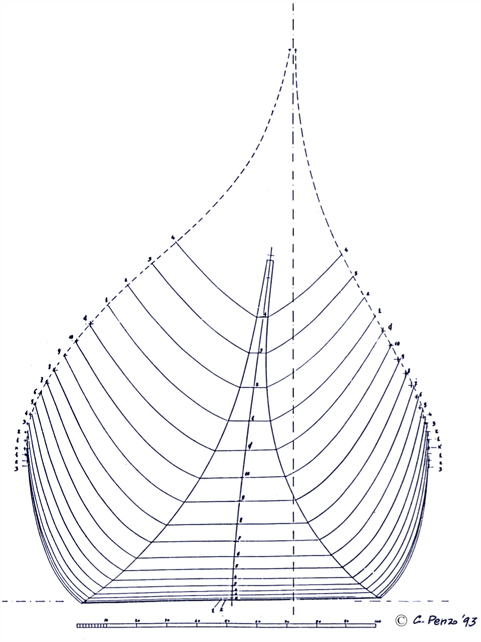

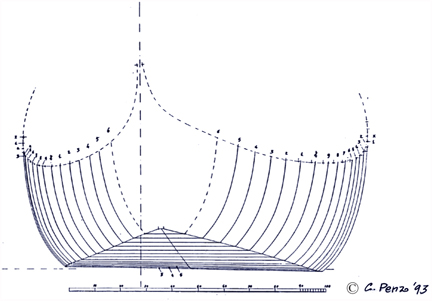

A year passed. Every so often, I went to visit him and to have a look at the project, feeling not a little like Catherine the Great stopping by to see how the Hermitage was progressing. I spent the good part of one afternoon watching him curve the oak boards that would form the sides of the gondola. This required that they be kept wet on the top while he played a blowtorch across them from below as he molded the eleven-meter planks into the proper shape. The frame took a year, and then he began to insert the sancón and the piàna, the stabilizing bars that run from side to side of the bottom and would eventually be covered by the floorboards or pagiòl. I realized how much an exercise in three-dimensionality the construction was, for the two sides curve up – as if the boat were a giant lopsided banana – to encompass a hollow space, and the builder must continually calculate just what is next and where it is going to go in relation to the other pieces.

As another year passed, the area covered by his project expanded, until one room of the carpenter’s workshop was filled with lengths of wood, rectangles of wood, rods and strips and pegs and pieces for which there is no English – and no Italian – name. Not only had a large section of the workshop been turned into uno squero, but one of his workbenches was now home to scores of oddly-shaped pieces of wood. Stranger still, the Italian carpenter often asked the American to explain to him the details of cutting and planing the nómbolo (side planks), pirón (wooden bolts and nails), and pontapìe (inclined wooden brace for the gondoliere’s back foot). As to the trèsso, the carpenter’s uncertainty might result from this definition given it: ”listelli fissati sull’orlo interno di alcuni sancóni per sostenere rispettivamente il sentàr, le banchéte e il tristolìn da próva inferiore”. Obviously, these are instructions that make sense only to a Venetian gondola builder. Eventually, the carpenter was to observe the creation of more than two hundred structural and semi-structural, functional and non-functional parts, including a large number of simple wooden planks. Here I should add that the gondola, unlike the jigsaw puzzle, does not come with ready-cut pieces. The person – though it is virtually unheard of that a single person should attempt it – who builds the boat has to cut each piece by hand or machine and shape it so precisely that it fits smoothly into the pieces around it. Water-tight, remember?

Another year passed, and my friend arrived at the trasto de mèso and began thinking about where to find the most beautiful fórcola, upon which the oar is braced, though I had learned enough by then to realize there was going to be no need of a fórcola for some time yet, at least a year. The fórcola can’t be slipped into place until the entire boat is completed, but I chose to interpret his interest as optimism, not magical thinking. As the boat grew, the room began to clear: less space was taken up by unused pieces, just as the closer one comes to completing a puzzle, the fewer pieces lie loose on the table.

Towards the beginning of the fourth year, he reached the point of constructing the parti decorative, the sentolìna and the caenèla. By then, the carpenter had been transformed from a rent-collecting Saul to a Saint Paul, fully converted and eager to participate, although my friend allowed him to help only with heavy lifting, never with the actual work of construction.

When the frame was complete, it was necessary to caulk, which is done with thin strings of cotton that must be soaked in resin and then wedged into the tiny grooves between the interlocking boards from which the boat is built. These strings are sealed in place with repeated coats of resin; later, before it’s painted, pitch will be used to seal the complete interior of the gondola.

While he’s busy sealing up the boat to make sure it’s watertight, let’s go back to Artù, the Fritz Wunderlich of Palazzo Curti Valmarana. Through the days and evenings of a hot summer, the tourists floated by, the accordionist played, and Artù conquered. An American movie producer, hearing Artù in concert, talked of the possibility of his appearing in a cameo role in a new film version of Romeo e Giulietta. Even though we knew that the words of American film producers are as permanent as what is written on the waters of the Grand Canal, a few of us permitted ourselves an evening discussing costumes and shooting angles. I remember one heated discussion of whether Artù’s right profile was better than his left and from which side, therefore, to film him. I’m afraid I grew quite severe here and suggested that, should negotiations ever lead to this point, the only place from which to shoot Artù was the floor.

Time passed, and his owner did not hear from the producer, and finally the film was made without Artù’s artistic contribution. He, however, continued to sing. As the months went by and I heard the repertory of the human singers time after time, I realized that the two most often-sung songs that waft their way up and down the waters of the Grand Canal are those Neapolitan classics, “Torna a Sorrento” and “O sole mio.” Was a Venetian dog meant to sing along to these? What, I wondered, was the music that was really meant to be sung from the gondola?

By the middle of the fifth year, the gondola was caulked, coated with countless layers of resin, painted, and judged to be watertight. All of the decorative parts were in place, the fórcola bought, and two metal ferri attached at front and back. It was time to launch the gondola. To do this, it was necessary to find enough strong men to take it from where it rested in the wooden cradle in the carpenter’s workshop and carry it first to a truck. Thirty-two men answered the casting call, a panoply of muscles such as life seldom presents us. They lifted the gondola, all 350 kilos of it, and carried it slowly towards an eight-wheeled heavy transport truck. The driver lowered the winch and then lifted the boat into place on the cradle where it would rest until it reached its destination.

The trip took an hour. I followed behind in a friend’s car and thus could see the heads of drivers and passengers whip around as the truck passed them. A gondola? On the autostrada?

In Tronchetto, the parking lot at the end of the bridge from the mainland, another winch cradled the gondola and lifted it from the truck, then lowered it gently into the water. As soon as they heard the story, the people in the growing crowd at the dock, lined up on the edge, waiting to see if it would sink or swim.

It swam, and the heroic builder finally climbed down into his boat, walked to the back, and took the oar that a friend handed down to him. In jeans and tennis shoes, without a straw hat, and with no Neapolitan singer at midship, he started to row away from the dock, heading towards the entrance to the Grand Canal.

Those of us who had come along with him to Venice to watch the launch started to cheer, and soon we were joined by the workers on the pier. Our shouts and whistles must have created a strong wind or current behind him, for very soon he disappeared into the darkness under the railway bridge. Then, a few long minutes later, he appeared again in the sunlight on the other side, turned in an arc to the right, and disappeared into the beginning of the Grand Canal. This time, it was the assembled dock workers and boatmen who started to cheer, and soon we were all standing there, pounding one another on the shoulder, cheering at the boat that was finally on its way towards home.