Taking a Closer Look

Despite some changes in its form, the gondola we see today, gliding effortlessly through the waters of Venice, is easily recognizable as the same boat that floats through the work of the great painters of Venice: Bellini, Canaletto, Carpaccio, Guardi. To walk through any museum where their paintings or drawings are on display is to identify, not only the gondola, but the familiar buildings and bridges of the city, just as faces identical to many of the subjects in those paintings can today appear behind the counter of a bar or across a Venetian dinner table. Part of the fascination of the city surely rests in the fact that the past is so ever-present genetically as well as linguistically and architecturally.

Though there is speculation, though no certainty, about the origins of this very strange boat, today it is seen as the quintessential Venetian. Its name has changed, though there is philological dispute about the nature of that change. Some insist that the original name came from Greek, “kóndy” (cup). Or perhaps the origin is the Latin “concula” (small shell) or “cymbula” (little boat). The first written evidence of the current name comes from a 1094 decree by Doge Vitale Falier, making mention of the “Gondulam”.

The symbiotic relationship, if that’s what it is, between Venice and the gondola puts one in mind of the chicken-egg dilemma. Which came first, an exquisitely maneuverable, light boat that a single man could propel effortlessly through shallow, reed-lined canals and so save the population of the Veneto from the hordes of invaders from the North? Or was it the growing need to flee into the marshy land off the coast of what is today Venice that required the construction of a boat that could carry people to safety? Bear in mind, as well, the tremendous advantage had by a rower who is looking forward as the boat moves and is thus able to see what dangers lie ahead. A change in tide, unexpected by the invaders in their deep-keeled boats, who were unfamiliar with channels and tidal patterns, would ground them in the mud of receding waters, leaving them easy targets for the Venetians, intimately familiar with every curve their canals made through the marshes. The gondola is not likely to be confused with a man-of-war, but there can be no question of its tactical superiority in the marshy terrain that is its home territory.

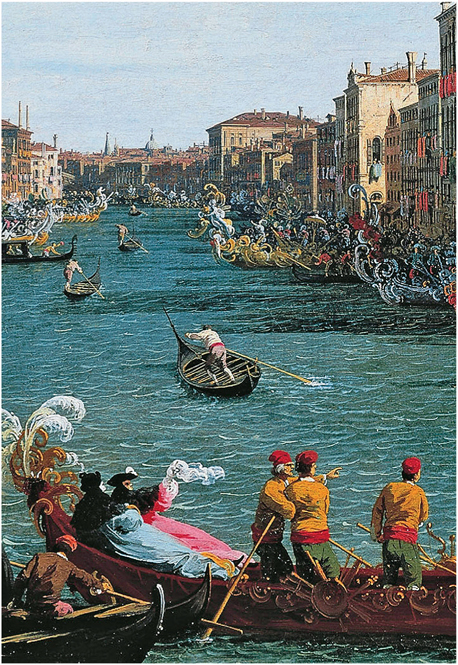

By the early part of the Sixteenth Century, Venice no longer at risk of invasion, the name “gondola” was in common usage, as was the boat, though this one was symmetrical and rowed by two rowers, one on either side. What distinguished it from other boats of similar lineaments was the use to which it was put. The others, even those rowed by men in the standing position, transported heavy loads of products and produce meant to be sold and were used primarily for commercial purposes. At that time, the gondola was used almost exclusively for the private transport of persons of a certain rank. This fact would certainly help explain why it was the gondola upon which Venetian craftsmen lavished their attentions, in hopes of making it ever more beautiful, ever more eye-catching, ever more sellable. In our times, stuffed teddy bears are occasionally tied onto the front of sixteen-wheeled trucks, but it is the ornamentation of the Maserati that causes heads to turn.

Today’s gondola, the one in which tourists are given their view of the back canals of the city, dates from the Nineteenth Century, when the boat builders Casal and Tramontin began to build the slimmer, asymmetrical gondolas we nowadays know. It is an elaborate construction, sometimes taking a squad of specialized workers as long as two years to complete. Its wooden pieces are still made of the same eight types of wood: fir, larch, oak, elm, cherry, mahogany, lime, and walnut. Almost 11 meters long, its flat bottom reduces the resistance to the water and renders it both fast and agile, as can be seen any year during the regatta, when both professional and amateur gondolieri display the remarkable skill with which they make these wooden boats move and turn.

It is said that a fully-laden gondola, loaded with passengers to a total weight of 700 kilos, can still move at the rate of a walking man. Further, the gondoliere who is rowing that mass exerts no more energy than if he were walking at a normal pace.

Both residents and tourists make frequent, quotidian use of those workhorse gondolas, or traghetti, which take people from one side to the other of the Grand Canal. They are to be found at Rialto (though this one finishes running at lunchtime) at Santa Fosca, San Tomà, and in front of the Hotel Gritti. These gondole have two oarsmen who effortlessly take twelve or more standing passengers across the canal for a mere seventy cents each. Tourists and non-residents have recently been zapped and must now pay two Euros to cross the Canal, while residents still pay the lower resident price. Considering the glory available on both sides of the Canal, and no matter which fare is paid, this ride might well be the greatest tourist bargain in the world.

The gondola’s perfection lies in seeming imperfection. The boards making up the left side are longer, thus curving the asymetrical prow to the right. This would, obviously, render an ordinary boat unmaneuverable and condemn it to endless circles, no matter how carefully its two ordinary rowers worked. The force propelling the gondola, however, comes from only the right side and thus the disproportion works to the advantage of the single rower at the stern as he thrusts his weight forward to dig his oar into the water. At the end of his stroke, he slides the oar from the water, shifts his weight while bringing the oar forward, suspends it what seems only a millimeter above the water, only to slip it in again and continue his journey.

Though the gondolieri wore elaborate costumes in former times, created by specialized tailors, hat- and shoemakers, today their attire is reduced to an optional straw boater with a red ribbon and a black and white striped shirt, but there is no standard uniform. The trousers are usually black, though white Nike tennis shoes often peek out from beneath them. The only constant in appearance is the gondola itself, which is always black. There are many romantic (is “invented” the better word?) stories to explain this. There is the legend that the gondola wears black for those who died in the plague, or to mourn the city’s conquest by Napoleon (though they were black centuries before that.) There exist records of sumptuary laws passed concerning the gondola – an attempt on the part of the city to keep its citizens from wasting their money in the attempt to outdo one another with ever more elaborate and ever more expensive decoration for their boats. So far as I have been able to learn, these laws were concerned more with excessive decoration than with color.

The gondola is made waterproof by being caulked and painted inside with pitch, and then many coats of resin are put on the outer shell before it is all covered in black paint. Always black nowadays, never white, say, or grey. Or yellow. Or even gold, as the ambassadorial gondolas – diplomats being exempt from the sumptuary laws – painted by Marieschi approximately in 1735, blindingly bright, looking as though it had been minted rather than built.

The choice of black might be explained by practicality, no surprise from a people as practical as the Venetians. Consider for a moment the perils presented by the geography of the city; think of water traffic, and waves, and drunken boatmen, and amateurs out for their first try at rowing, and narrow canali and sudden turns. And rough stone walls. Any one of these elements can lead to collision or scraping, as they still often do. What happens to the long black streak on the yellow – or white – hull, after the other guy has rowed beyond sight or hailing? What if the gondola is moored behind the palazzo, and a freak wind bangs it against the stone wall one night? How much easier to cover the scrapes by slapping on a few layers of black paint rather than try to match the original color. I am not certain that this is the reason the gondola is black, but it is a possibility and certainly makes as much sense as a vow made by gondolieri to thank God for saving the city from the plague. Or Napoleon.

Another way the gondola has changed – and the paintings of the Venetian school give endless evidence of its previous ubiquity as part of the gondola – is in the removal of the central cabin, the felze. The origin of its name, like that of the gondola, is disputed: the usual suspect is the Greek phýlakos, or protection, but no certain source can be found. Originally intended to protect passengers from the elements, it was made of thin cloth attached to a frame of wooden rods arching from one side of the gondola to the other, left open in front and back. Giovanni Mansueti’s beautiful “Miraculous Healing of the Daughter of Benvegnudo” in the Gallerie dell’Accademia catches a brightly-dressed gondolier in the act of assembling the felze, its cloth as bright and patterned as those of his jacket and stockings. The lightness of fabric and construction suggest that the entire construction could easily be disassembled and removed from the gondola.

A hundred years later, most felzi had become as black as the gondola, and with the passage of another century, they became a permanent and unremovable wooden element in the gondola, now with thicker cloth as lining and curtains. Open windows on the sides, as well as the openings at front and back, allowed for greater visibility from inside as well as for the passage of more air through the enclosed space during the hot months. One has but to think of the smoke-glassed limousines and SUV’s which often cruise by in the fast lane to get an idea of the effect: there was no way to see inside, though the passengers were free to view what was going on around them, if only by pulling back the curtain a few centimeters. Or, in the nineteenth century, by peering through one of the cracks in the wooden shutters that covered the side windows and the doors to the front and back openings, shutters which are now called, at least in English, Venetian blinds.

Pause and consider for a moment this situation: the man or woman of a noble house is enclosed and invisible inside the cloth or wood of the felze, so thick as to protect him or her from the sun or wind, cold or damp. But think, if you will, from what else might the virtual invisibility provided by the felze protect a person. The eyes of neighbors? Friends? Wives? Husbands?

Rowing at the stern was the gondoliere, the only servant who who was treated with easy familiarity by his masters. He was young, tall, gaily dressed, strongly muscled. It is said and often written that the gondolier knew the family secrets and the intimate details of the private behavior of both husband and wife. Many stories are told of how attractive gondolieri often were, both to men and to women. The gondola – which was a house without being a house – was considered as “un luogo d’incontor” (a place for meeting) and the one person who would always know what went on during those encounters was the gondoliere. Or perhaps he played a part in them?

But let us leave such base thoughts behind and move to the essential decorative element of the gondola, i ferri, the metal ornaments that sweep up from front and back of the gondola and add so much to its mysterious profile. Il fèro da próva, at the front, serves as a fourteen-kilo counterweight to the gondoliere at the back. Many sources state that the six forward-looking bròche (teeth) represent the six sestieri of the two main islands, while the single backward-looking bròca stands for la Giudecca, which is geographically separated from the others. The arched neck of the fèrro is said to be the image of the Rialto Bridge, though its equal resemblance to the peculiar cap or corno worn by the Doge of Venice is sometimes offered as an explanation. The fèro da pòpe, at the back, is a far less elaborate thing and is there primarily as protection against bumps and scrapes.

Decorated nails placed between the bròche do the work of attaching the ferro to the frame of the boat. It is well worth visiting the Museo Correr and the Naval Museum to have a look at their collections of head-spinningly beautiful ferri from gondolas of the last centuries. These examples of the genius of Venetian craftsmen seem, in certain lights, to be made of lace, so delicate is the tracery of figures and arabesques, so light-filled the open spaces. Closer examination reveals their solid fraternity with the carving on the oriel windows on so many Venetian palazzi, where masons worked the same magic with stone and succeeded in making that material appear just as gossamer and weightless as these beaten rods of iron. No wonder the city authorities, after calculating how much time went into creating ferri rather than useful things like spears and cannons, struck back with sumptuary laws that criminalized the iron workers for the production of mere beauty and threatened repeat offenders with eighteen months service in the galleys or three years in prison.

The fórcola, carved from a single piece of walnut root, is the navigational heart of the gondola, for it is in the mòrso (opening) that the gondoliere rests his oar while pivoting to make a new stroke. The fórcola must provide different leverage points for the single oar and thus allow the skilled gondoliere to maneuver his gondola through busy canals and narrow waterways.

The evolution of the fórcola can also be studied in the work of the major Venetian painters. It gets shorter, taller, thicker, the second mòrso disappears; it tilts out from the side of the gondola and then moves back closer. The design and carving, however, are on a straight trajectory toward abstract beauty of line and finish. For a time in the nineteenth century, it was painted black, but then taste changed, and it returned to its natural wood finish.

The gondoliere is entirely dependent upon the fórcola to provide a base and pivot for his oar during the countless strokes he makes each day. Only three craftsmen in Venice produce them today, and gondolieri treat them with near-reverence, seeing that they are kept well-rubbed with linseed oil and a home-made paste of Vaseline and oil of Vaseline, a process which will help them last a lifetime. Each one is crafted to a specific gondoliere, with the maestro taking into account his height and weight as he carves the wooden block. One unusual thing about the fórcola is the impossibility of finding anything to compare them to: the fórcola looks like a fórcola, and that’s the end of it.

The examples so richly provided by Venetian painters fail to provide accurate information about the last element of the gondola, the oar or remo, quite simply because most painters showed them where they spend most of their time: under water. Thus it is difficult to give evidence of how much or little the remo has changed through the centuries. Most are made of beech and are about 4.2 meters long. The blade tapers and grows both wider and thinner at the end, to facilitate its passage through the water and to increase the power of its thrust.

The gondola, then, is a composite of apparently odd pieces put together with rigorous accuracy, still assembled in the same way as it has been for hundreds of years. The clothing of the people walking on the streets of Venice today looks different from the clothing of those who walked here a half a millennium ago. The articles in the shops of this most commercial of cities are entirely different. Yet the fabric of the city remains the same: the same facades, the same hand-made glass in some windows, the same paving stones. And gliding by, there is the same dark shadow with the single man standing in the back, calling out a soft “Oii” to warn of his coming.