Chapter 22

Ten Fascinating Facts about Professional Ballet Dancers

In This Chapter

Why they’re called “bunheads”

Why they’re called “bunheads”

About those pointe shoes

About those pointe shoes

Body first + party later = long(ish) career

Body first + party later = long(ish) career

Ballet dancers give their life energy in order to transform the theater into another world — to involve the audience so completely that they forget about their daily grind. This is the ultimate reward for any live performer.

But in order to create this illusion, ballet dancers have a daily grind of their own. For every single hour of new choreography that you see onstage, dancers put in about 60 hours of rehearsal time. Here’s a look at the true lives of ballet dancers.

The Discipline Needed to Be a Dancer

Most professional ballet dancers decide on their career when they’re in their early teens — and most begin training before the age of 10. At that early age, they choose to set aside team sports, school parties, and hanging out at the mall for battements , dégagés, and hanging out at barres.

Young ballet students practice for an average of ten years before they are ready to join the ranks of professional dancers. That’s ten years of daily stretches, classes, and rehearsal — and then the work really begins.

After they get into a large professional ballet company, dancers spend about 30 hours per week in the rehearsal studio — plus up to 15 hours warming up. Outside the studio, dancers spend time getting physical therapy, massage therapy, and chiropractic care, sewing five to ten pairs of pointe shoes per week, cross-training at the gym, putting their hair into the requisite bun (for women), adhering to a special diet, and refraining from any activity that could jeopardize an optimal performance — usually for a small salary.

Some young dancers eat, drink, and think of nothing else but ballet — inspiring the term bunheads.

A Dancer’s Schedule: A Day in the Life

A dancer’s day usually starts with a hot bath or shower to loosen up the muscles, followed by light stretching at home. At the studio, it’s back onto the floor for serious stretching, followed by the structured warm-up known as ballet class.

Ballet class is offered nearly every day at every professional ballet company. Some dancers choose to skip class and warm up on their own, but the class offers an opportunity to do it together, under the watchful eye of a ballet master. Ballet class begins with the same barre and center floor exercises that we show you in Chapters 6 through 13, and continues with imaginative combinations of steps — danced to the accompaniment of a long-suffering (but cheerful) rehearsal pianist.

After class, dancers have about 15 minutes to change into dry dancewear, have a snack, complain about ballet class, and fill up on water. Now the serious rehearsing can begin. Dancers often rehearse for three hours at a stretch, with five-minute breaks each hour. Afterward they get an hour for lunch — and then it’s back to the studio for three more hours of rehearsal. In a typical rehearsal day, a dancer may rehearse as many as six different ballets.

On performance days, the dancers generally have only two hours of rehearsal. Then they try to fit in a massage, dinner, and a nap before going to the theater. In most companies, dancers must sign in half an hour prior to curtain time.

After the performance, most dancers are ravenous; and this is when they eat the most. Then it’s home to unwind — and off to sleep, while visions of sugarplums dance in their heads.

What Dancers Actually Eat

In a word, carbs.

Carbohydrates, and lots of ’em, are the staple of any dancer’s diet. Bagels and coffee for breakfast, bananas, apples, and orange juice after class, sandwiches and salads and tofu and rice (and the occasional potato chip) for lunch.

Of course, the amount of food consumed at breakfast and lunch is usually small, because rehearsals are coming right up. If you’re about to get held upside down in the air by your partner, a light lunch is a good idea.

Dinner tends to be on the hefty side. But even here, carbs are paramount. A large salad, followed by a helping of pasta, is a typical dinner. And some low-fat protein, like chicken, beans, or tofu, helps charge up for the next day.

Of course, dancers don’t eat healthy all the time. We’ve been involved in plenty of dancer pizza parties. And most dancers have a drink or two now and then at the end of the day — after eight hours of grueling exercise, why not?

And chocolate’s good, too. One piece at a time.

The Hierarchy of a Ballet Company

Not all dancers are created equal. And ballet companies make sure that you know this. Most companies divide their dancers into at least three different levels.

At the highest level are the Principal Dancers. These dancers get most of the meaty roles — Siegfried and Odette in Swan Lake, Giselle in Giselle, and so on. (At the Paris Opera Ballet, those roles go to an even higher level of dancer — the étoiles, or “stars.”)

Just below the Principal Dancers are the Soloists. These dancers usually get to dance featured roles, but often take part in group scenes as well.

Below the soloists are the members of the corps de ballet. The corps is the largest group of any ballet company, and the heart and soul of any ballet. When you see that line of 32 women in white doing arabesques in unison, or the crowd scenes and Wilis in Giselle, that’s the corps at work.

Below the corps are apprentices, who are usually hired on a yearly basis. They may or may not ever become permanent members of the company. They dance along with the corps most of the time.

And below the apprentices are the students of a ballet school, which is usually attached to any major ballet company. These are the mice and soldiers and party children in Nutcracker, and they occasionally get to participate in crowd scenes of other ballets.

There is no guarantee that a member of the corps will ever be promoted to soloist, or that a soloist will ever be promoted to Principal Dancer. As a result, dancers sometimes leave one company for a higher position in a smaller company. (Big fish — small pond.)

The Mysterious Pointe Shoe

Ask a great ballerina if you can try out her pointe shoes, and she’ll probably back away slowly, shoes behind her back, offering calm, soothing pleasantries, until she’s far enough away to bolt into a dead run.

Shoes are a very personal topic for ballet dancers. Eventually, every ballerina has to learn how to balance on the tips of her toes. To help her achieve this feat, she has several pairs of pointe shoes (see Figure 22-1).

Pointe shoes are handmade from such things as canvas, newspaper, and acrylic cement. (Just how we, as a species, determined that these materials go well together is beyond our imagination. But suffice it to say that “canvas, newspaper and acrylic cement” are right up there with “peanut butter and chocolate” in the inspired combinations department.) Those materials are shaped into the appropriate form, and then topped with a layer of satin, with a leather sole.

Like ballet slippers, pointe shoes have drawstrings to tighten the top part of the shoe. (Don’t ever let a pointe shoe dealer talk you into buying drawstrings as optional equipment. They’re standard.)

The part of the shoe that surrounds the dancer’s toes is called the box. The box comes in various lengths, widths, and degrees of hardness in various places (such as along the sides). The only thing all ballerinas agree on is that the box should have a flat tip to stand on. Contrary to popular belief, this tip is not made of steel. But the dancer’s toes are.

Today there are many different makers of pointe shoes, and some have incorporated new materials available today into the construction of a “new and improved pointe shoe”. But most dancers today are purists, and their pointe shoes aren’t significantly different than they were a century ago. We highly recommend pointe shoes constructed by Freed of London.

When a ballerina gets a new pair of shoes, she has to break them in. She bends and softens the leather soles. She pounds on the boxes for awhile, or slams them in a door a few times, to make them more flexible. She whacks the points of the shoes against a cement floor to soften them a bit and prevent them from making too much noise onstage. No wonder she’s so attached to the things.

After all the work that goes into making pointe shoes and preparing them for your foot, you’d expect them to last a long time. But nothing could be further from the truth. In the heat of performance, a pair of pointe shoes can last for as little as 30 minutes before the box becomes too soft to dance in. A typical ballerina needs three pairs to get through a single performance of Swan Lake — and up to 150 pairs a year. That’s about 8,000 shoes for a typical ballet company. Luckily for the dancers, the company pays the bills.

|

Figure 22-1: The mysterious pointe shoe. |

|

Why Macho Guys Dance

In America, many male dancers start taking ballet because their sisters do — and then discover the challenge and physical workout to be fun. Some are even captured by the thrill of performance. And lots of ’em enjoy hanging around with a bevy of perfect beauties. But no doubt, young male dancers in the United States often have to endure ribbing about their chosen activity.

But in some other countries, like Russia and Cuba, the motivation is different. In those cultures, a male ballet dancer is the equivalent of a sports hero. And why not? The virtuosic pyrotechnics of these professionals are not to be believed. Being the principal dancer of a ballet company is just as cool as being a basketball or football star.

Women, Pregnancy, and Performance

Every woman who has had a child knows how wacko the female body gets during pregnancy. How does a dancer deal with the added stress of pregnancy on her body, when her body is her instrument?

For a ballerina, whether or not to get pregnant in the first place is a huge decision. Most ballerinas at the highest level decide to wait until they finish their career before having a baby. Still others decide to retire early while their biological clock is active.

But many ballerinas get pregnant, have kids, and still practice ballet brilliantly. We know many professional ballerinas who have safely performed ballet into their fourth and even fifth month of pregnancy.

Why Some Ballet Dancers Need Hip Replacements

.jpg)

Some dancers are so determined to be more turned out than anyone else that they end up ruining their hip joints completely. Some need hip replacements as early as in their 40s — and because hip replacements only last about 20 years, that means at least one upgrade on each side. Ouch!

Party versus Performance

Dancers are notorious for loving a good party. (And man, are they amazing at discos.) As a result, some dancers walk a fine line — usually early in their careers, as members of the corps de ballet.

But most dancers — at least the smart ones — eventually realize that partying interferes with performance quality. As a result, they have to pass up wonderful temptations every day.

Like all art, ballet demands a sacrifice. A huge one. But a dancer who’s willing to make that sacrifice is often rewarded with a beautiful career. And when the career’s over, they can party all they want.

Early Retirement

Even if a dancer lives right, eats right, makes all the right decisions, gets enough sleep, maintains a healthy lifestyle, and manages to avoid major injuries, he or she can still expect to retire early. A good professional dancing career usually lasts 10 to 15 years. And a typical retirement age is between 30 and 35. What then?

Some dancers go back to school to begin a totally unrelated career. But others choose to pass on the flame. These dancers become artistic directors, ballet masters, choreographers, and dance teachers. Their new passion is keeping the art alive for the next generation.

Why It’s All Worth It

So why do dancers do what they do? Why is a dance career worth this daily grind, insane discipline, risk of injury, little pay, no guarantee of promotion, and early retirement?

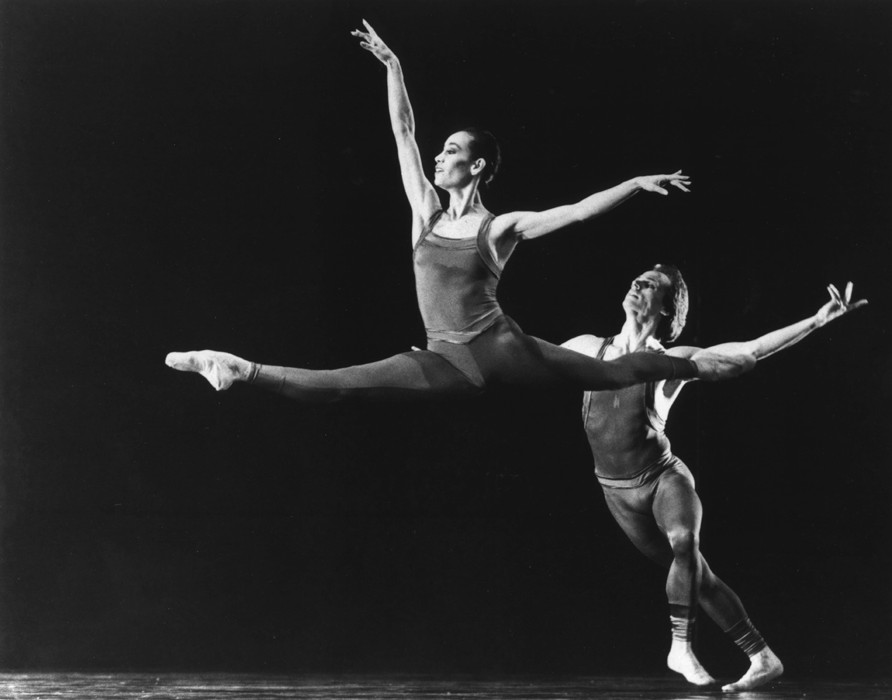

It’s worth it for those rare moments when everything comes together in performance, when the dancers create something bigger than themselves, and when the audience responds enthusiastically as one (Figure 22-2).

And deep down, ballet dancers love every bit of their work. Scratch the surface of the most jaded professional, and you’ll find that bunhead who just lives for her art.

|

Figure 22-2: Evelyn Cisneros and Tony Randazzo in James Kudelka’s The End. |

|

© Marty Sohl