Chapter 4

Leaping into Ballet Basics

In This Chapter

Finding the correct ballet stance

Finding the correct ballet stance

Walking like a duck

Walking like a duck

Getting your feet and arms into position

Getting your feet and arms into position

Forming a graceful ballet hand

Forming a graceful ballet hand

All right, then! If you tried the warm-ups in Chapter 3, your body is toasty and you’re ready to go. But before trying out any ballet step, you need to understand certain basic concepts. You wouldn’t attempt brain surgery without a little training, would you? (Note to Mrs. Hallie Mae Beauregard of Galveston, Texas: Don’t answer that.)

In this chapter you can encounter — possibly for the first time in your life — the strange ways that ballet dancers stand, balance, turn out, point their feet, and do all the things that make ballet what it is.

Finding the Correct Ballet Stance

Have you ever noticed the way a ballerina carries herself? Haughty, imperious, and unapproachable, right? She owns the world. She has utter self- confidence. She thinks very little of anyone else. Or so it seems.

The fact is, many ballet dancers are rather shy about what they do. (You would be too, if everyone mistook you for a snob.) But the ballet stance that inspires this misconception is a basic part of classical ballet technique, for men and women alike. Don’t worry, though — if you’re old enough to read this, you are in no danger of having this stance become permanent. You’ll be able to turn it on and off at will.

One of the big goals of ballet is creating the illusion of elegance and poise. A certain confident ease of motion perpetuates this illusion. But that’s exactly what it is — an illusion. Deep down, every ballet dancer is just as neurotic as you are.

Locating your center

If you were to videotape a world-class ballet dancer in action, and then stop the tape at any given frame, the ideal dancer will always appear graceful and balanced. This remarkable phenomenon applies to other pursuits as well — tai chi, for example, or thumb wrestling.

The key to this appearance is centering. As a potential ballet dancer, the first thing you need to do is find your center — the position in which you can rest in total balance. Here’s how the pros do it:

1. Stand at the mirror, facing sideways, with your feet parallel to each other.

2. Engaging your thigh muscles, straighten your knees — but without pushing back into your knee joints.

3. Lift your abdominal muscles upward and back towards your spine.

This is called pulled-up position. Imagine that you are placing your ribcage over your hips. Think of your neck as an upward extension of your spine. Your shoulders are relaxed downward, and your chin is slightly lifted — hence the haughty air.

4. Curve your arms so that they are rounded and just in front of your thighs, and bring your weight forward into the balls of your feet.

You should be able to lift your heels slightly off the floor (see Figure 4-1). At first, you may feel as if you are about to fall forward onto your face. In fact, you have our permission to fall forward a few times. But with practice, this alignment becomes much more natural.

Now that you have found your placement, or center, you are ready for anything. All ballet movements begin from here, allowing the upper and lower sections of your body to work together as one.

.jpg)

Keeping your spine in line

As you go through your daily routine — driving to work, sitting at the computer, flirting at the gym, scolding the kids — gravity has a way of causing your shoulders and head to slump. For aspiring ballet dancers, defying gravity is a good and healthy thing. Good posture is helpful for ballet — and for the rest of your life, as well.

Be aware of your posture during all the down times in your day, such as the time you spend standing at the bus stop or in the checkout line. Locate your center (see the preceding section) during these activities and see how this posture differs from your “normal” stance.

Even as you sit reading this book, you can perfect your posture. Move to the edge of your chair and align your spine over your hips. Thanks to the chair, you don’t need to hold any muscles to stay seated — instead, you can just rest your spine in-line over your hips. You and your back will be happier together for your efforts. And you’re on the way to good ballet posture.

|

Figure 4-1: Finding good placement for ballet technique. |

|

Adjusting your posture for balance

In addition to aligning your spine, you need to be able to adjust your posture for different ballet positions. In order to maintain balance while your legs and hips move in a certain direction, your upper body moves in opposition to your lower body.

For example, say that you want to lift one leg behind you. In order to maintain balance, the weight of your upper body has to adjust slightly forward. When lifting your leg to one side, you adjust your body slightly to the other side to create balance. When lifting your leg to the front, you adjust your body slightly to the back. Got it?

Of course, these adjustments are very small. But the smallest adjustments make all the difference and lead to safe dancing.

Distributing and transferring your weight

Standing on one leg

.jpg)

Lift your left leg off the ground, bending your knee outward slightly. Now, pointing your left foot, place it in front of your right ankle (Figure 4-2a). Notice how much you must shift your weight to your right foot to maintain your balance.

|

Figure 4-2: Shifting your weight to create balance. |

|

Now return your left leg to the starting position and repeat this exercise on the other leg.

Shifting onto one leg

Begin by bending your knees as far as you can while still keeping your heels on the floor (Figure 4-2b). Lift your left leg, just as you did in the preceding section, bending your knee outward. Point your left foot and let the toes touch your right ankle as you straighten your right knee. Bring your arms in front of you, rounded at the level of your ribcage. The goal — eventually — is to arrive in this position with your arms and legs at the same time. Notice that the weight shift to the ball of your right foot is more extreme than before. That’s because your right leg has gone from bent to straight.

After you master this shift, do the movement on the other side. We wouldn’t want you to develop a lopsided technique!

Balancing on the ball of your foot

Okay — we’re getting advanced now. Here’s the ultimate test in the transferring of weight. This exercise is similar to standing on one leg, but with a twist — this time, you balance not just on one foot, but on the ball of that foot.

Begin with your knees slightly bent, heels together, toes pointing outward. Keep your arms at your sides, low and rounded, with your fingers almost touching your thighs. Lift your left leg, with your left knee pressing outward, foot pointed, with the toes touching your right ankle. Meanwhile, rise up on your right leg, straightening the knee

.jpg)

Don’t be dismayed if you don’t get the hang of it right away — it takes a lot of practice. And don’t worry if you find it much harder to balance on one foot than the other. Everybody has that problem.

Keep in mind that when you go to the ball of your foot, your balance must be very precise. After all, you’re balancing the entire weight of your body on about 4 square inches. It’s like trying to hold up a broomstick by balancing the end in your upturned palm. It may take a very long time to find the balance — with the help of strong abdominal muscles to keep yourself stabilized. But when you do find that balance, it feels effortless. And that’s the most glorious feeling in the world.

The strange thing is, with the right adjustments, you can balance in any position. So here’s the bad news — although you may find a balanced position, the position may not be “correct” in the classical sense. That’s why every ballet studio is plastered with mirrors from floor to ceiling. Dancers are constantly checking their positions — all positions, all the time.

What’s my line?

Look closely at a good photo of any ballet dancer, and you can see that the positions of his or her body seem to create long, imaginary lines. In many positions, you can clearly draw a line from one end of the body to the other. Some lines are straight, others are curved — but all the lines look graceful and connected.

A recent ingenious advertising campaign for the San Francisco Ballet showed photographs of dancers in beautiful positions, superimposed with geometric designs that corresponded exactly to the lines created by their bodies. These designs helped everyone to experience one of the most beautiful aspects of ballet: the concept of line.

The entire body participates in the creation of a line — from pointed foot to leg to torso to arm to hand — with the head and neck enhancing the line, as well. Even a dancer’s eyes can help, by gazing exactly in the direction that continues the line. Ideally, these lines seem to extend far beyond the body of the dancer, off into space. Even when the dancer stands still, you get a sense of motion and constant expansion. Achieving this feeling is the Holy Grail of classical ballet technique. And dancers work daily toward that goal.

Walking Like a Duck: Proper Leg Alignment

If we’ve heard it once, we’ve heard it a thousand times — almost every ballet dancer walks like a duck. And the fact is, that’s true. Not that it’s a conscious choice or anything. But many dancers, after years of indoctrination into correct classical ballet posture, find the duckwalk to be a comfortable way of getting from one place to the other.

We know what you’re thinking: “Stop right there! If Chapter 4 of this book is going to make me look like a duck, then what will I look like by Chapter 22?”

Not to worry. Once again, unless you have practiced rotating your hips outward for at least four hours a day, several days a week, from the tender age of nine, you’re in no danger of walking like a duck. Worst case scenario, you may temporarily take on some chickenlike tendencies. But it’s worth practicing this technique a bit now, just to get the hang of it.

Turning out your legs

Working on turnout on the floor

.jpg)

1. Lie on your back with your legs straight, resting on the ground.

2. Lift both legs over your hips, bending your knees if you like.

Your feet should end up directly over the bottom of your rib cage.

3. Flex your feet.

This helps you see the difference between the parallel and turned-out positions.

4. With your feet parallel, press your inner thighs together, as if you were holding up a $1,000 bill.

Or, if you prefer, use your thighs to hold up this book.

5. Rotate your hips outward, causing your feet to point away from each other with your heels touching.

Naturally, your thighs may separate when you do this. (There goes the book!) But the trick is to keep your thighs reaching for each other. Stay in this position for a few seconds.

Repeat this exercise, alternating at least ten times between the two foot positions. You may want to do this exercise to music to make this experience more pleasant!

Aligning your body

The key to staying injury-free in ballet, and in everything you do, is to keep your body aligned. We know, we know — easier said than done. After all, ballet is all about complex movements. But whether you’re standing, leaping, or spinning, you need to avoid twisting at all times. Here’s an example: When you stand with your knees bent, you put a significant amount of stress on your knee joints and leg muscles. This stress can lead to injury if any part of your body is twisted. So plant each foot broadly on the floor. Keep your ankles relaxed, not gripping. Hold your knees directly over the center of your feet. Keep your pelvis directly over your heels, without sticking out your rear end. As you bend your knees, your hips move down without moving back and forth — like a horse on a merry-go-round. Now you’re aligned.

Developing turnout on your feet

After you develop a flat-on-your-back mastery (or at least understanding) of turnout, you can give it a try on your feet.

Stand upright with your feet parallel. Now, keeping your heels together, and moving from the hips, rotate your legs and feet outward in one smooth motion. Don’t overdo it — just go as far as you can without strain. This is your natural amount of turnout.

How much turnout do you have? Well, in the beginning, you may not have much. In fact, as you practice, you may not even notice the incremental improvements. Ballet dancers take years and years to improve their turnout. But because all ballet positions and movements start from the rotation of the hips, the time is well spent.

Point those feet!

We hear it all the time in the ballet studio: “She has such beautiful feet!” What on earth could cause a dancer to fixate on the second ugliest part of the body — let alone extol its virtues?

In actuality, this comment refers not to the feet themselves, but the way in which they can bend . Ballet dancers work for years — years! — on the concept of pointing their feet.

We know — foot-pointing is a bizarre choice for a life goal. But the fact is, ballet dancers have to point their feet almost every single time their feet leave the floor.

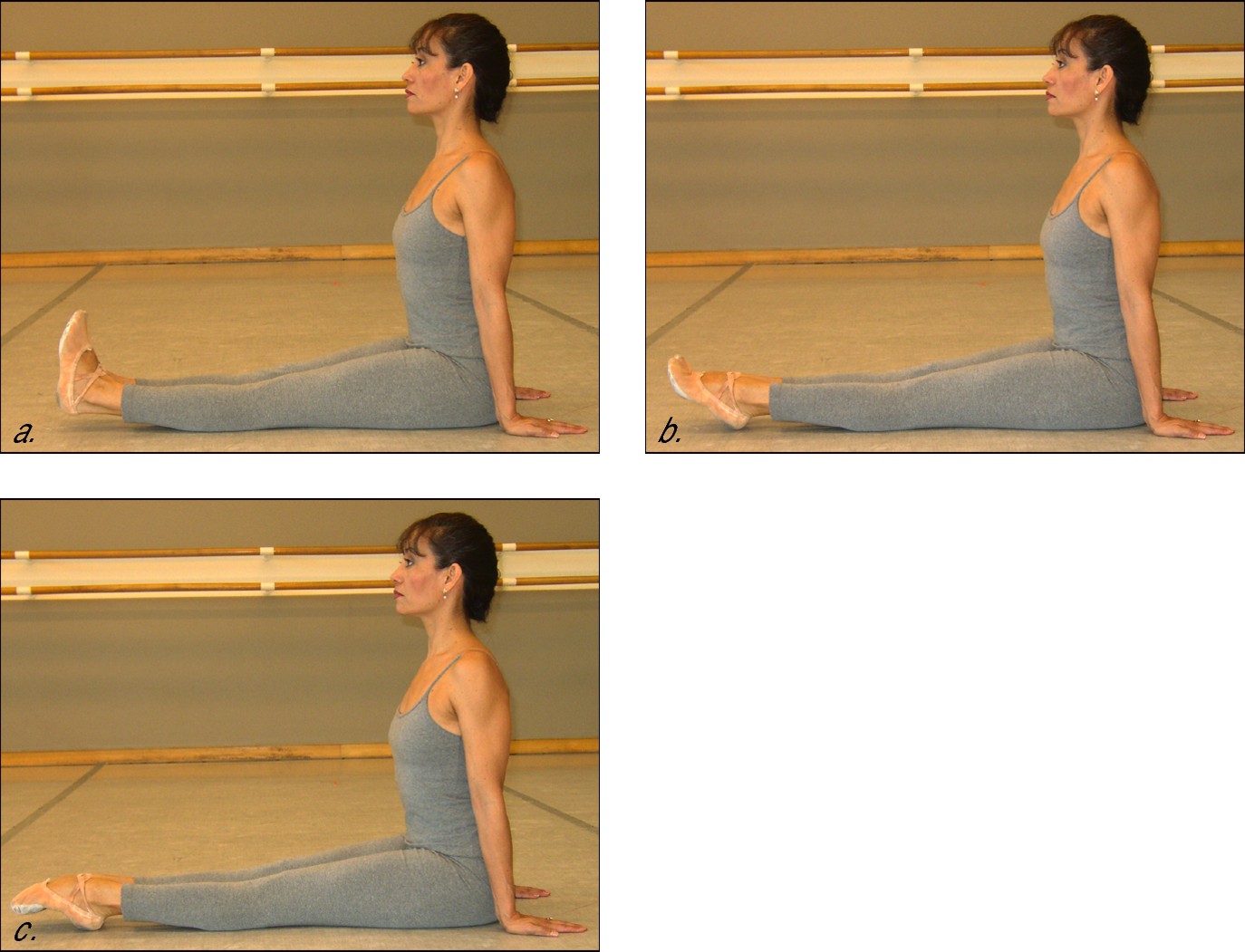

1. Sit on the floor with your back supported and your legs in front of you, with straight knees.

2. Flex your feet, drawing your toes toward you, so that your toes point to the ceiling (Figure 4-3a).

If your calves are well developed, the act of flexing your feet may cause your heels to lift off the floor a bit. That’s perfectly okay.

3. Bend your ankles so that your toes point towards the wall in front of you (Figure 4-3b).

Keep bending — within reason, or course — until you can’t reach any farther. Make sure that your feet point as an extension of your shinbone, and that your feet don’t curve to the inside or outside.

4. Now reach your toes down toward the ground (Figure 4-3c).

Don’t crunch your toes, but rather make them an extension of the curvature of the feet, creating the longest line possible. Need we say it? Don’t hold this pose too long, or your feet will begin to cramp.

5. Engaging the toes back towards the sky, follow through with the ankles until you return to the original flexed position.

Just for fun, try this variation on the exercise. Point your feet as you did in Steps 3 and 4. Then, with your feet still pointed, rotate your legs out from the hips. Voilà! Turnout, plus pointed feet. You’re a ballet dancer at last. Careful, though: In this position, you have to work extra hard to keep the feet pointing straight.

|

Figure 4-3: Pointing your feet. |

|

Practicing the Positions of the Feet and Arms

We’d like to pause just a moment to give thanks for the fact that we have only two legs and arms. Just with these four basic limbs, the permutations for ballet seem almost unlimited.

But in reality, every ballet move has at its core one of the basic positions. There are six possible foot positions and five arm positions.

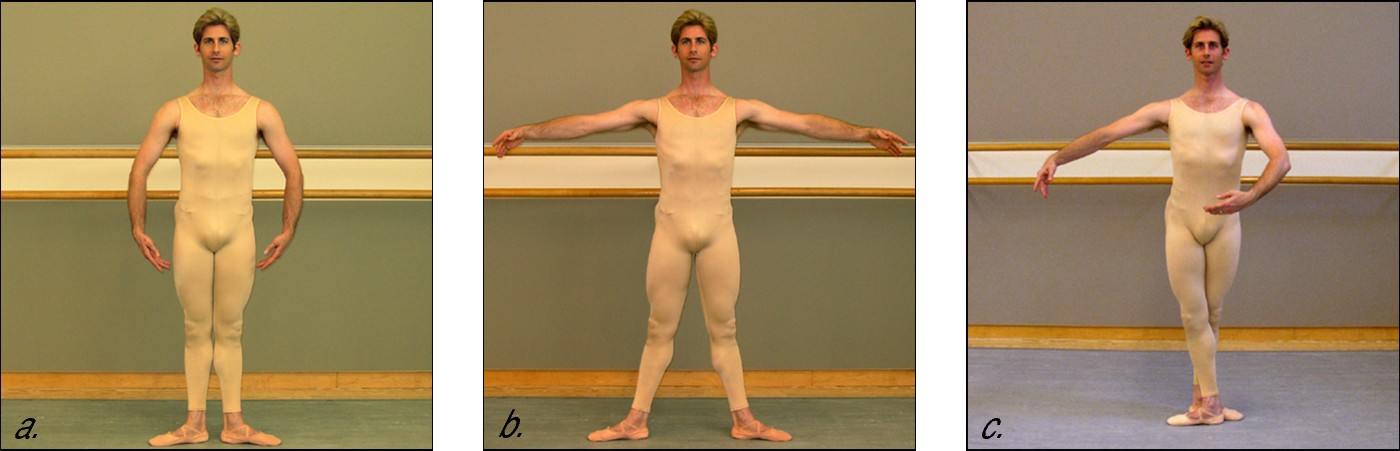

First position

If you have practiced weight distribution and leg turnout (see the sections earlier in this chapter), you have already discovered first position.

Stand straight, your heels touching, your toes pointed outward — like Charlie Chaplin. Keep your arms rounded, to the sides of your body, with your fingertips just off the thighs at the middle of your legs. Keep your shoulders down, neck long, and chin slightly lifted (Figure 4-4a).

|

Figure 4-4: First (a), second (b), and third (c) positions. |

|

First position is so fundamental, so common, and so important in ballet, that we use it as a point of departure for many steps.

Second position

Starting in first position, slide one foot straight out to the side, and point your foot. Now lower your heel so that it lines up with the other. Redistribute your weight evenly on both feet. Your knees are straight, and your toes remain pointed outward. This is second position — basically a spread-out version of first position.

Now for the arms. From first position, lift them to the side, while keeping them slightly rounded. The palms of your hands should be visible from the front, with your elbows slightly lower than your shoulders, and your wrists slightly lower than your elbows. Your shoulders are down with your neck long and your chin slightly lifted (Figure 4-4b).

Third position

Unlike first and second positions, which are symmetrical, third position involves putting one foot in front of the other. For that reason, you can do third position in either direction. Start off by going to the right.

From second position, bring your right foot in front of your left foot, so that your right heel touches the middle of your left foot, just below the bunion joint. Your toes still point outward, and your knees are still straight. Keep your stomach lifted. This is third position.

.jpg)

In this position, the arms work in opposition to the legs. If your right foot is in front, your left arm should be in front. In this case your left arm is rounded, with the fingertips lifted to about belly button height. Meanwhile, your right arm is rounded to the side, with the palm of your hand forward, also at about belly button height (refer to Figure 4-4c).

Third position can be done in reverse — to the left — simply by reversing your legs and arms.

Fourth position

From third position, slide your right foot forward, away from your left, so that your right heel is directly in front of the left big toe joint, by about the length of one foot (not 12 inches, but the actual length of your own foot).

You are now in fourth position — the most challenging of all the positions. Keep your knees straight and your hips facing forward as much as possible, with your stomach lifted.

As in third position, your arms work opposite from your legs. Bring your left arm forward, rounded, with your fingertips the height of your breast bone. Your right arm is to the side, slightly rounded, with the palm forward (Figure 4-5a, the dancer on the left).

From here you can create another, alternate arm position. Lift your left arm, rounded, over your head and slightly forward. Be careful not to lift your shoulder when you lift your arm. This is the high fourth position , as shown in Figure 4-5a, the dancer on the right.

|

Figure 4-5: Fourth position: low and high (a); fifth position: arms low, middle, and high (b). |

|

Fifth position

From fourth position, close your right foot in front of your left foot — so that your right heel is directly in front of and touching your left big toe, with your toes pointing outward. Keep your knees straight and try to keep your hips facing forward without twisting, with your thighs, stomach, and the gluteus engaged, lifted and firm.

First, with your arms rounded and your palms facing you, bring your arms together so that your fingertips are approximately six inches apart and in front of your thighs. This is low fifth position (refer to Figure 4-5b, the dancer on the left) or in French, en bas — “ahn BAH” — which simply means “below”.

From this position, bring your arms up, rounded, in front of your breast- bone, creating a downward diagonal line from shoulders to elbows to wrists (refer to Figure 4-5b, the dancer in the middle). This is middle fifth position (en avant — “ahn a-VAHN” — literally, “ahead”).

Finally, lift your arms up, over, and in front of your head, still rounded, with your hands approximately six inches apart, your palms facing inward (refer to Figure 4-5b, the dancer on the right). How high should your arms go? Without moving your head, look up — you should be able to see your hands. This is high fifth position (en haut — “ahn OH” — meaning “on high”). This is the position every child copies when imitating a ballerina; it’s been used on more music boxes than any other position.

It’s all French to me

We had to bring it up sometime — the uncomfortable topic of French. If you eavesdrop on any ballet studio on earth, you hear a lot of French words. Because so much of classical ballet technique was developed in France, the French names for things stuck. So when ballet dancers talk about a particular move, they almost always use the French name for it.

We don’t use much French in this book, but we have to use some. We’re not yielding to ingrained snobbery, or blind adherence to the past, or even a preference. It’s just convenience. Very often, a French term serves as an incredibly handy abbreviation, or shorthand, for a concept that would take much longer to describe in English.

Here’s an example: In describing a particular move, we could say, “Stand with your legs turned out, heels together, toes pointing outward, knees bent as far as you can while keeping your heels on the floor, without allowing your rear end to stick out, keeping your spine straight, shoulders down, neck long with your chin slightly lifted and your arms rounded to the sides of your midthighs.”

Or we could say: “Demi plié in first position.”

So in the interest of avoiding a 12,000 page volume, we introduce you to some French terms, bit by bit, throughout this book. But not to worry: All of the French terms we use are fully explained, with pronunciations, in the handy glossary at the back of this book.

And we promise to be gentle. After all, French is the language of love.

Sixth position

In the old days, five positions were enough. They sufficed for centuries, in fact. But with the recent turn of classical technique toward contemporary style, sixth position was born. For that reason, sixth isn’t usually considered part of the basic classical ballet positions. But sixth position appears so frequently today in choreography that you should be familiar with it.

Sixth position is the easiest of all. It’s the closest position to the way non-dancers stand. Your feet are parallel, your toes pointing straight ahead, and your knees are straight. Your upper body is lifted, with your chin slightly raised. No arm movements to worry about. We knew you’d like sixth position!

The Graceful Ballet Hand

If you think feet are beautiful, let’s talk hands. There is so much beauty in the hand of a ballerina: delicate and fragile as a flower, airy as a spacious sky, fluid as an amber wave of grain. Hands have a life of their own, but they also exist as extensions of the arms, continuing their lines smoothly, just as this final clause gracefully brings this sentence to a close.

In classical ballet, the key to a beautiful hand is relaxation. But the technique varies slightly depending on what gender you happen to be.

For male dancers, the hand should accentuate a feeling of strength with ease . Therefore, the hand must be relaxed, but shouldn’t become limp, flaccid, or otherwise dysfunctional. (See the upper hand in Figure 4-6.)

For ballerinas, old-fashioned, politically incorrect feminine grace is the goal. To practice this, shake your hand out in front of you; then let your hand go limp. Extend your index finger to elongate it slightly; now do the same with your little finger. Next, gently draw in your thumb so that it is directly under your index finger. None of the fingers should be straight (which would look stiff) or curled under (which would shorten the all-important long line). Your fingers should neither appear glued together nor spread far apart from each other. (See the lower hand in Figure 4-6.)

|

Figure 4-6: The graceful ballet hand — male and female. |

|

Having said all that, there are infinite variations to the shape of a dancer’s hand. And that’s a good thing, because the hand can be a huge help in portraying a character. For example, in the ballet Swan Lake, the ballerina dancing Odette the Swan Queen may consciously choose to keep her fingers aligned in a row, giving the appearance of feathers.

Yes, it’s true — duck feet, swan hands.