Chapter 7

Stepping It Up at the Barre

In This Chapter

Coordinating one leg on the floor with one in the air

Coordinating one leg on the floor with one in the air

Cooking up fondus and frappés

Cooking up fondus and frappés

Horsing around

Horsing around

Chapter 6 introduces you to the basic warm-up exercises at the barre. This chapter picks up where that one left off — and makes up the middle group of barre exercises that most ballet dancers do in sequence every day.

In this chapter you pick your legs up off the ground (one at a time, that is) and sustain a higher lift than before. Don’t worry — you can start very slowly. You’ll soon be amazed at what you can accomplish with your two lower appendages.

Melting into a One-Leg Knee Bend (Fondu)

Although this exercise is called the fondu (“fon-DUE”), it bears very little resemblance to melted cheese. It is so named because, after you master this exercise, you get to eat whatever you want.

Actually, the French word fondu does indeed mean “melted,” and it’s a good description of this step. To do a fondu, you start from two legs, and — by gradually bending both legs and transferring all your weight to one leg — you lower yourself closer and closer to the floor, like a Gruyère that has gotten a bit runny.

As you are about to discover, the best way to master this exercise is in the so-called cou-de-pied position.

The so-called cou-de-pied position

Simply put, the cou-de-pied (“KOO de peeAY”) position is a pose in which one foot is slightly raised off the ground. You can do the cou-de-pied position to the front and to the back.

.jpg)

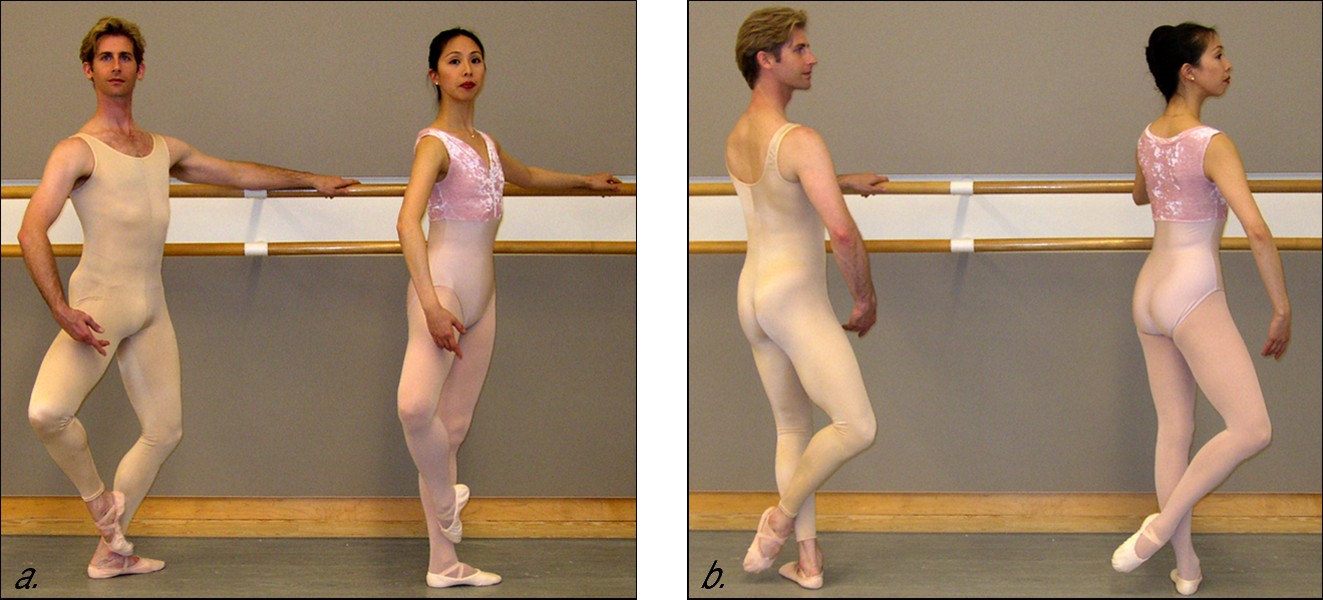

Cou-de-pied position in front

To do the cou-de-pied to the front, follow these steps:

1. Supporting yourself well with your left leg, lift your right foot off the floor. As you do, bend your right knee slightly and turn it outward.

2. Touch your pointed right foot to your left ankle at the bone that sticks out on the inside of your ankle.

Because your feet are turned out, that bone is facing forward. The heel of your right foot should be just forward of your right toes.

There you have it — the cou-de-pied front position. (See Figure 7-1a, the dancer on the right.)

|

Figure 7-1: The cou- de-pied position in front (a) — with and without a fondu added — and in back (b) — with and without a fondu. |

|

Now for the fondu.

1. Begin in the starting position and repeat the cou-de-pied front motion. But this time, as you lift your right foot, do a demi-plié with your left leg.

By the time you are in the cou-de-pied position, you have reached the deepest point of the demi-plié. That is the fondu to the front (refer to Figure 7-1a, the dancer on the left).

Time to come up.

2. Bring your right foot back into fifth position as you straighten both knees simultaneously.

Cou-de-pied position in back

Well done. Next, try the cou-de-pied back position. Once again, begin in the starting position, but this time with your right foot behind your left.

1. Lift your right foot into cou-de-pied back position, as shown in Figure 7-1b, the dancer on the right.

Make sure that the toes of your right foot are pointing back, and the heel of your right foot is touching your left leg at the lower attachment of the calf muscle.

2. Now return to the starting position, right foot in back.

Fondu time.

From this starting position, do the same motion again — but add the demi-plié (refer to Figure 7-1b, the dancer on the right).

That’s the fondu in back.

When you feel comfortable with these motions, try them with your legs reversed. Begin in the mirror image of the starting position: the barre at your right side, right hand on the barre, feet in fifth position with your left foot in front, left arm in low fifth position.

Mixing the fondu with the battement tendu

You can combine the fondu with just about any of the motions from Chapter 6. To begin, try a fondu followed by a battement tendu to the front.

.jpg)

1. Stand in the starting position, with one slight change: Bring your right arm into second (arm) position.

See Chapter 4 for more information on arm and leg positions.

2. Do the famous fondu with your right foot in cou-de-pied front position.

3. As you straighten your left leg to come up again, extend your right leg in front of you — into the forward battement tendu position that we show you in Chapter 6.

Your right leg should arrive in the forward position, with a straight knee, just as you straighten your left knee.

Need another challenge? It’s time to involve your right arm.

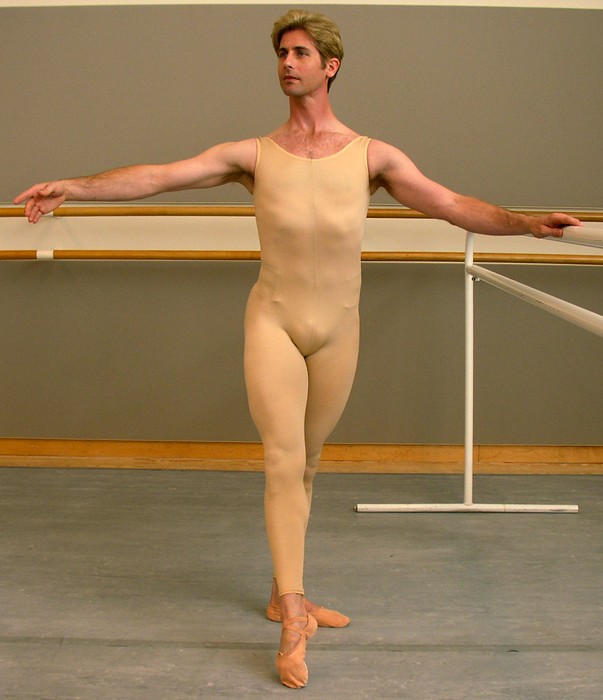

4. Do another fondu. This time, as you reach the lowest point, bring your right arm to middle fifth position. Then, as you straighten your left knee and move your right foot forward into the battement tendu, open your right arm, arriving in second (arm) position at the same moment that your leg arrives at its final destination (Figure 7-2).

That’s it!

|

Figure 7-2: Coming out of the fondu from cou-de-pied front position, ending in a battement tendu to the front. |

|

Now try the fondu again, followed by a battement tendu to the back, with your right foot in back. Move your right arm exactly as you do for the battement tendu to the front.

Finally, repeat the battement tendu to the side and finish by closing in fifth position with your right foot in front, just as you began.

Don’t skimp on this or any other exercise: Do this exercise to the front, side, and back. Then, get into the mirror image of the starting position (turn so that the barre is to your right) and repeat the whole exercise using your left leg.

Try the following combination to get some practice mixing the fondu and the battement tendu. For this combination, go out and find yourself a tango recording. Either that, or you can use the instantly recognizable Habanera from Georges Bizet’s opera Carmen. Count this music in groups of eight, where each count lasts about two seconds. (See Chapter 5 for more info on counting music.)

1. Stand in the starting position. For the first 4 counts, do nothing.

2. Over counts 5 through 8, bring your right arm up from low fifth to middle fifth position and open it to second position.

3. Over counts 1 through 4, do a fondu in the cou-de-pied front position, going to a battement tendu in front.

Meanwhile, bring your right arm up through low fifth to middle fifth position (for the fondu) and open to second position (on the tendu).

4. Over counts 5 through 8, and then again over the next counts 1 through 4, repeat Step 3 twice more.

5. Over counts 5 and 6, do a fondu in the cou-de-pied front position. Over counts 7 and 8, close to fifth position with your right foot in front and the right arm in second position.

6. Over counts 1 through 4, do a fondu in the cou-de-pied front position, going to a battement tendu to the side.

Meanwhile, bring your right arm up through low fifth to middle fifth position (for the fondu) and open to second position (on the tendu).

7. Over counts 5 through 8, do a fondu in the cou-de-pied back position, going to a battement tendu to the side.

The right arm follows the same path and timing as in the fondu to battement tendu exercise earlier in this chapter.

8. Over counts 1 through 4, repeat Step 6.

9. Over counts 5 and 6, do a fondu in the cou-de-pied back position. Over counts 7 and 8, close to fifth position with your right foot in back, and the right arm in second position.

10. Over counts 1 through 4, do a fondu in the cou-de-pied back position, going to a battement tendu to the back.

Meanwhile, bring your right arm up through low fifth to middle fifth position (for the fondu) and open to second position (on the tendu).

11. Over counts 5 through 8, and then again over the next count 1 through 4, repeat Step 10 twice more.

12. Over counts 5 and 6, do a fondu in the cou-de-pied back position. Over counts 7 and 8, close to fifth position with your right foot in back, and the right arm in second position.

13. Over counts 1 through 4, repeat Step 7.

14. Over counts 5 through 8, repeat Step 6.

15. Over counts 1 through 4, repeat Step 7.

16. Over counts 5 and 6, repeat Step 9, and close to fifth position with your right foot in front.

17. To finish, lower your right arm to low fifth position.

Switch sides and do this exercise in the opposite direction; that is, with the barre to your right.

Combining the fondu with the dégagé

Up to this point you have done the fondu in the cou-de-pied position, and you have done it adding battement tendus. Now, following the traditional ballet sequence that has been in place for centuries, the next step is to do the fondu adding the dégagé positions from Chapter 6.

If you’re worried about adding the dégagé, have no fear! This is one of the easy steps. It’s just a matter of extending your leg a few inches off the floor — to just a little under a 45-degree angle.

.jpg)

1. Do a fondu with your right leg in the cou-de-pied front position. Meanwhile, bring your right arm through middle fifth position.

2. As you come back up from the fondu, extend your right leg out in front to the dégagé position, and bring your arm out to second position, just as you did in the previous exercise.

In opposition

In the ballet world, you often hear the term opposition. In order to achieve the balance needed in many ballet moves, your muscles often have to work in opposite directions at the same time.

A classic example of opposition is the fondu relevé. As your standing leg raises up on the ball of your foot while the other leg is in the cou-depied position, your body invariably wants to turn in toward your standing leg. In order to counteract this, you must keep the knee of the coude-pied leg pressing outward.

For this reason, we would never describe any ballet position as static, or motionless. There is always motion, even when your audience (or your dog) can’t see it. In ballet, work is being done at all times throughout your body.

If you don’t have a split personality already, your body soon will.

After this move feels comfortable, try the motion to the side. Start with another fondu — but while straightening up, do a dégagé to the side.

Bring your leg in for another fondu , but this time in the cou-de-pied back position. Repeat the step a few times more — always alternating where your right foot returns to cou-de-pied . Front, back, front. Finish by closing in fifth position with your right foot in back .

Now try a fondu opening to dégagé to the back, and return to the cou-de-pied back position. Repeat that motion at least twice more, and on the last repetition, close to fifth position with your right foot in back.

Next, try a fondu opening to dégagé to the side, and return to the cou-de-pied front position. Finally, do this move two more times, alternating cou-de-pied back and front, and close to fifth position with your right foot in front.

You may have noticed that when you repeat these exercises, your foot doesn’t necessarily close into the fifth position “resting place” for each fondu. Of course, repeating the exercise without stopping is much harder on your muscles — and that’s a good thing. These repetitions work to develop long muscles, great strength in your legs, and that “Ballet Butt” you keep hearing about.

To practice combining the fondu with the dégagé, just repeat the exercise you do in “Mixing the fondu with the battement tendu,” earlier in this section — same music and all. But in every step, you substitute the word dégagé for battement tendu. In other words, instead of extending your leg straight to the floor (tendu) as you straighten your knees, you extend it out to the 45-degree position off the floor (dégagé ).

.jpg)

Adding rises to the ball of the foot (relevé)

Time to ratchet up the challenge just one notch. This exercise includes all the elements of the previous fondu exercise in this section — plus one more: the relevé. As you may remember from Chapter 6, relevé means “lifted up again.” In this exercise, you add a little rise onto the ball of your foot.

The so-called fondu relevé is the ultimate antigravity exercise. It lifts you at the very top of your hamstrings — just where they attach to the base of the glutes. As a result, your legs and glutes become much firmer. And as you develop the control needed to execute this move well, you build a tremendous amount of strength.

.jpg)

1. Do a fondu on your left leg, with your right foot in the cou-de-pied front position. Meanwhile, bring your right arm through low fifth position.

2. Straighten your left knee and rise up on the ball of your left foot.

Your trusty authors shall now attempt to lower you down.

3. As you lower your left leg from relevé, touch your left heel down to the floor, and then bend your knee into a fondu.

See sidebar “Hiding the seams” for tips on how to do this gracefully.

Of course, this move can be done in all the same directions as the other fondus . We suggest you repeat all the fondu positions, enabling you to concentrate on the addition of the relevé each time. The art of ballet is nothing if not thorough.

Adding the retiré

In the retiré (see Chapter 6), your standing leg is straight and turned out, while your other leg is lifted, knee bent outward, with your toes touching your standing leg just below the kneecap.

The retiré is often combined with fondu exercises at the barre. From any fondu in cou-de-pied front position, straighten your standing leg, bringing the toes of the working leg (that is, the leg you’re not standing on) up your shinbone to your knee. There you have it — a fondu to retiré front.

As you can find out in Chapter 10, the relevé in retiré is the position used in ballet turns, or pirouettes. Of course, everyone seems to want to do pirouettes, and for good reason — they’re fun! But they take a lot of work to master, and this is the first step.

A complete fondu combination

Time to pick your favorite moves and put them together. To create the ultimate fondu combination, you can include different moves from earlier in this section. The constant is the fondu — you melt into a one-legged knee bend again and again. But every time you come up out of the fondu , try alternating between battements tendus, dégagés and retirés. And to add a little spice, occasionally go up on the ball of your standing foot as well (relevé ).

Hiding the seams

Within any given minute of ballet performance, the average dancer may go through 100 different moves. Of course, to the average viewer, the performance is one long, fluid, beautiful motion. The secret? Not showing the seams.

For example, in a typical relevé, the standing leg has at least two things to do: straighten the knee, and rise up onto the ball of the foot. These motions follow a specific sequence — the dancer always straightens his standing knee completely before rising onto the ball of his foot. However, these movements follow in such quick succession that they appear to be a single motion.

For the reverse motion, the same concept applies: As the dancer comes down from the relevé into the melting fondu, the standing heel touches the floor just before the knee begins to bend.

Seamless, man, seamless!

For music, we recommend any tango music. Count the music in groups of 8 counts, where each count lasts about one second.

The Pas de Cheval (Horse Step)

Horses hold a special fascination for ballet dancers, and ballet dancers are often compared to thoroughbred racehorses. Perhaps the reason is the beauty of dancers’ musculature, the leanness in their legs and long necks, or the perception that, like horses, they were simply created for graceful movement. Or perhaps the reason is that like horses, ballet dancers drink a lot of water, love to herd together, and tend to kick when provoked.

Whatever the essence of this fascination, it must be a long-standing one, because someone long ago named a step in the classical ballet vocabulary the “horse step,” or pas de cheval (“PAH duh shuh-VAHL”).

To understand the inspiration for this step, think about how a horse walks. As each hoof lifts off the ground, the ankle bends so that the hoof remains a little behind the rest of the leg. Then, as the leg extends towards the next step, the hoof comes forward to meet the ground. This is the motion used in the pas de cheval.

.jpg)

1. Lift your right foot into the regular cou-de-pied front position.

2. Extend your foot to the front as if you are going to the dégagé, and place your toes on the ground in the battement tendu front position.

There you have it — the pas de cheval.

3. Now bring your right foot back to close in front of your left, in fifth position.

It does look an awful like the action a horse makes; aren’t you glad you don’t walk like that?

Now you know the drill — repeat the step in all directions. Starting from fifth position with your right foot in front, do a pas de cheval to the side; then close in fifth position with your right foot in back. Now horse-step to the back and close. Then complete the shape of the “cross” by repeating the step to the side;and finish in fifth position with your right foot in front.

.jpg)

Wait until about a minute into the music, after the harp plays a showy little solo. Then the orchestra starts to play an “OOM-pah-pah” rhythm, and from here the beat stays steady. Count this music in groups of eight.

1. Stand in the starting position. For the first four counts, do nothing.

2. Over counts 5 through 8, do a port de bras with your right arm, from low fifth, through middle fifth, to second position.

3. Over the next 16 counts, do four pas de cheval to the front.

Coupé on one, lift your right leg toward the tendu on two, reach the final tendu position with a straight leg on three, and close in fifth position with your right foot front on four.

4. Over the next 16 counts, do four pas de cheval to the side. Close in fifth position with your right foot in front the first time, and alternate thereafter.

5. Over the next 16 counts, do four pas de cheval back.

6. Over the next 16 counts, do four pas de cheval to the side. Close in fifth position with your right foot in back the first time, and alternate thereafter.

Repeat the exercise on the other side.

Striking the Floor with Your Foot (Battement Tendu Frappé)

If you’ve ever wondered how ballet dancers can move their feet so quickly and point their feet so sharply, you’re about to find out. The ballet world has devised an exercise to hone the feet like the toughest steel: the battement frappé.

As you may gather from the name — frappe (“frah-PAY”) is French for “struck” — this step is all about striking the floor with your foot. Beginning ballet students are sometimes encouraged to strike with an extra measure of aggressiveness.

The purpose of this exercise is twofold — first, to build strength; and second, to sharpen the reflexes in your lower legs and feet. When this move becomes second nature, you can point your feet faster than you can think about pointing them.

Every dancer works to achieve this instinctive ability — along with the satisfaction that your feet are pointing, even without conscious effort, every time they leave the floor.

Getting in position

Before doing the battement frappé itself, you need to get in position.

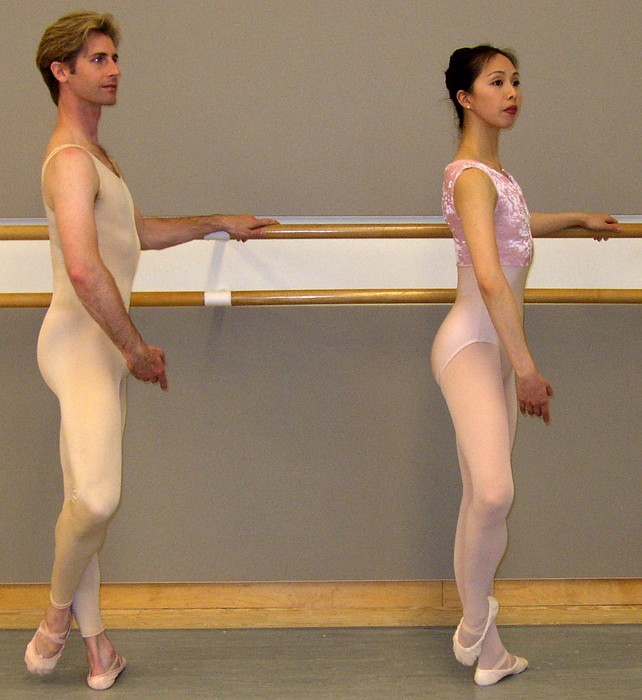

The starting position for the frappé is similar to the cou-de-pied position (see “The so-called cou-de-pied position”) — but imagine wrapping your right foot around your left leg like a snake. The French term for this is also quite similar: sur le cou-de-pied (“seur luh KOO de peeAY”) — literally, “on the neck of the foot.” If you didn’t think ballet was weird already, this may be the time to start.

Specifically, your right foot is wrapped about your left leg where the calf muscle lowers towards the heel (Figure 7-3, on the right). The position of the right foot on the left ankle stays the same whether the left foot is flat on the floor or raised up (in relevé ). Try it at the barre.

|

Figure 7-3: The sur le cou-de-pied position. |

|

As you’ve probably guessed, this move has a back version as well — the sur le cou-de-pied position in back. In that position, your right foot is in the exact same shape as when it is wrapped around your ankle, just move it to the back of your left leg (refer to Figure 7-3, on the left).

To the battement tendu

Before you add the striking motion that gives the battement frappé its fearsome moniker, see if you can do a few of the old familiar tendus, coming back to the sur le cou-de-pied position between them.

.jpg)

1. Brush your right foot to the side (battement tendu), and bring your right foot into the front sur le cou-de-pied position on your left ankle.

2. From here, do a battement tendu forward with your right foot, and then return to the sur le cou-de-pied position. Easy enough.

3. Next, try a battement tendu out to the side. When you return, bring your right foot to the sur le cou-de-pied position in back.

4. Now, of course, comes the battement tendu to the back. Return again to the sur le cou-de-pied position in back.

5. Finally, do another battement tendu to the side. Return your right foot to the sur le cou-de-pied position in front.

To the dégagé

Having mastered the preceding like a pro, you’re now ready for something a little more challenging. Time to ease into the frappé to the dégagé position, and strike the floor en route to your final destination.

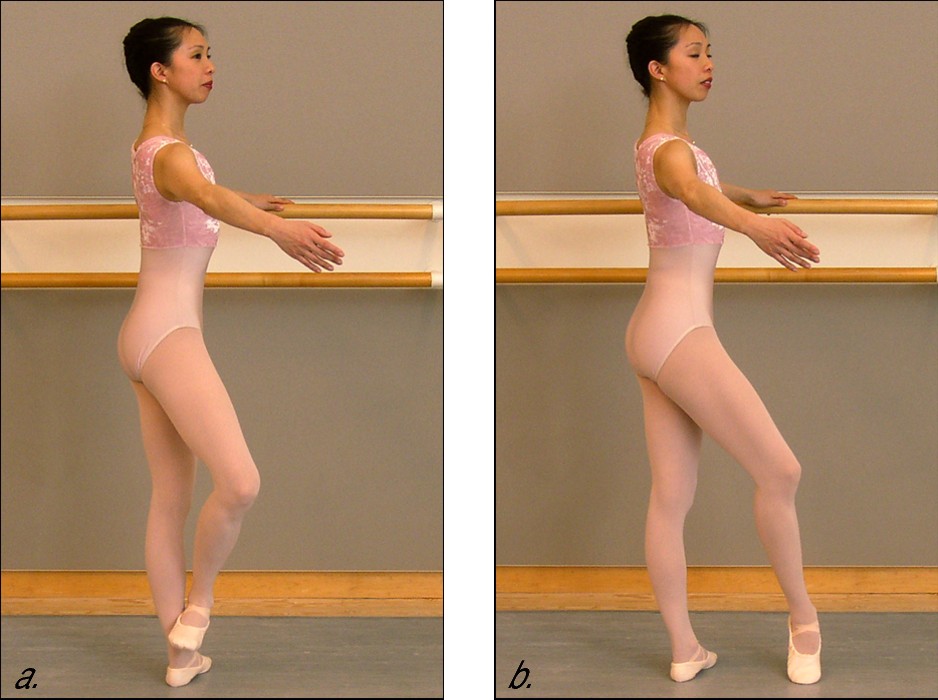

For this exercise, your legs need a new “ready” position — and this one is called cou-de-pied flexed. It’s very similar to the original cou-de-pied position you tried at the beginning of this chapter, with a twist. Literally.

Try getting into the old familiar cou-de-pied. Feel where your right pinkie toe touches the inside of your left shinbone. Now flex your right foot and touch your right heel to the same spot on the flat inner side of the left shinbone (Figure 7-4a).

|

Figure 7-4: The cou-de- pied flexed position for striking your foot in frappé, and the strike in the frappé. |

|

This position is not very balletic-looking, is it? That’s because, for practically the first time in your ballet career, you’re not trying to point your foot as it leaves the floor. The most challenging part of the frappé to dégagé is the coordination involved in alternately flexing and pointing your foot.

To do this exercise from the beginning, stand in the starting position. Now brush your right foot to the side (battement tendu ), and bring your right foot into the front cou-de-pied flexed position on your left ankle.

Now for some action! From the cou-de-pied flexed position, move your right leg out in front, as if doing a battement tendu dégagé, but a little closer to the floor. Halfway through the motion, suddenly and without warning, strike the ball of your right foot against the floor (refer to Figure 7-4b). Try to do this motion so suddenly that you surprise even yourself. Well, almost.

Actually, there is no need to use an excessive amount of force in this action — just enough to tap the floor, in an outward brushing motion. Your toes then point fully in the dégagé position.

Then return your right foot to the cou-de-pied flexed position without any floor contact — and repeat the exercise.

Now try the frappé to the side, going out to the dégagé as we show you in Chapter 6. Once again, strike the floor on the way out.

When you do a frappé to the dégagé back, the contact point of the “strike” is a little different. In order to maintain the correct turned out position of your foot, you have to strike with the pad at the inside and slightly under the big toe joint. Using the whole ball of the foot would be physically impossible. Unless, of course, you are put together quite uniquely.

Between the cou-de-pied

flexed and the dégagé positions exists an imaginary straight line, which is the path your foot must take in arriving at the end point. We hope this image will keep you out of the common trap of dipping your leg downward in the foot’s path. A dip in the middle of the motion gives the frappé a sluggish look.

Between the cou-de-pied

flexed and the dégagé positions exists an imaginary straight line, which is the path your foot must take in arriving at the end point. We hope this image will keep you out of the common trap of dipping your leg downward in the foot’s path. A dip in the middle of the motion gives the frappé a sluggish look.

You should execute the frappé with an “accent” — a sudden speeding up of the motion as your foot strikes the floor. Therefore, don’t perform this motion with a constant speed. If you were to divide the frappé into three counts, you would brush out and strike the floor on count 1, maintain the dégagé position on count 2, and close your leg back to the cou-de-pied flexed position on count 3.

You should execute the frappé with an “accent” — a sudden speeding up of the motion as your foot strikes the floor. Therefore, don’t perform this motion with a constant speed. If you were to divide the frappé into three counts, you would brush out and strike the floor on count 1, maintain the dégagé position on count 2, and close your leg back to the cou-de-pied flexed position on count 3.

Don’t forget — you are trying to develop a quicker response time for your lower legs. Your upper leg and knee remain serenely quiet and turned out as the striking takes place.

Don’t forget — you are trying to develop a quicker response time for your lower legs. Your upper leg and knee remain serenely quiet and turned out as the striking takes place.

A chocolate frappé combination

Here is a combination for practicing the famous frappé out to the dégagé positions (front, side, and back). For music, we suggest the Spanish Chocolate movement from Act II of Tchaikovsky’s Nutcracker.

This music is a very fast waltz: “OOM-pah-pah, OOM-pah-pah.” Give one count to each complete “OOM-pah-pah.” (In other words, every time you hear an “OOM,” count to the next number.) Count the music in groups of eight. After reaching 8, start over with 1 again.

1. Stand in the starting position. Over counts 1 through 4, do nothing.

2. Over counts 5 through 8, bring your right arm up through middle fifth to second position. At the same time, point your right foot and do a battement tendu to the side. Now close your right foot in the cou-de-pied flexed front position, ready to strike.

Your arm stays where it is, in second position.

3. Over the next counts 1 through 4, counts, do four frappés to the front.

Throughout rest of this combination, always reach the fullest extended dégagé position on each count, and always close back into cou de pied flexed between the counts.

4. Over counts 5 through 8, do four frappés to the side.

The first time, close your right foot in front, and alternate each time after that.

5. Over counts 1 through 4, do four frappés to the back.

6. Over counts 5 through 8, do four frappés to the side — alternating back and front.

7. To finish, close to fifth position with your right foot in front.

Or, if you’re feeling frisky, repeat the combination all around (en croix).

Now it’s time to do the exercise in reverse. Turn so that the barre is to your right, with your right hand on the barre, and repeat the whole exercise using your left foot.

Finishing with little beats (petits battements sur le cou-de-pied)

As is so often the case with ballet movements in isolation, you may find yourself asking, “Why the heck am I trying to do this?” The answer is that each exercise works as a building block for something much greater.

So it is with the little beats — petits battements sur le cou-de-pied (“puh-TEE bat-MAHN seur luh KOO duh peeAY”). The purpose of this exercise is to build up the strength and coordination needed to “beat” your legs while jumping, as if they were the wings of a hummingbird. These big jumps, usually performed by men, can make the audience gasp.

You’ve probably seen it — the Cavalier or Prince leaps into the air, flaps his legs back and forth innumerable times, and lands. Then, incredibly, he repeats that jump again and again.

.jpg)

1. Lift your right foot into the front sur le cou-de-pied position.

See “Getting in position,” earlier in this chapter.

2. Open your right leg to the side, from the knee down, so your foot just clears your left ankle.

3. Close your right foot into the back sur le cou-de-pied position.

4. Open your foot again to the side, and close it onto your left ankle in the front sur le cou-de-pied position.

If you held a pencil between the toes of your right foot during this motion, you’d scratch yourself something fierce. With enough practice, though, you could draw a narrow “V” on the floor: from the front of the ankle, to the side, and then to the back of the ankle. Then the pattern would reverse exactly, as if on a track. There you have it: Petits battements sur le cou-de-pied.

This sounds too easy to be true, doesn’t it? But the greatest challenge is not the exercise itself — it’s the speed. After ballet dancers get really revved up, they can do millions of repetitions per second. Well, at least two.

In fact, the only other body part that may legally move is your arm. And even then, your arm must have a mind of its own. While your leg moves quickly, your arm takes the slow road, most often using 8 counts to complete one full port de bras . It then takes another 8 counts to reverse the port de bras movement.

These petits battements work very well at the end of another combination. Feel free to add some to the end of your frappé combination — if you dare.

Little beats, big heart

The little beats (petits battements sur le cou-depied) may look easy, but they take enormous control. And to add even more to the challenge, they usually take place at exactly the point where the dancer would rather go lie down — the very end of a long combination.

An extreme example of this is the Grand pas de deux in Act II of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake. Odette, the Swan Queen, has just danced an enormously difficult set of adagio movements with Prince Siegfried. Now, as he strolls slowly around her, she must keep her entire body still — except for those quick beats of her right foot against the left leg.

We can tell you from personal experience that if you were in Odette’s shoes, the last thing you would choose to do is these little beats. You’re exhausted. Your muscles are screaming. And your left foot feels like it’s grinding a hole in the floor. To do these beats — and make them look as if you are a graceful swan shaking water from the tips of your wings — requires a fortitude not easily summoned.

Next time you go to Swan Lake, don’t forget to watch for this most special moment — and take pity on the ballerina and her left foot.