Johann

On the morning of September 3, 1786, so early the mist hasn’t lifted off the Töpel, and the sky shows no tender glimpse of dawn, a figure steps out of the Three Moors Hotel.

He is alone, encumbered by little more than a portmanteau and a knapsack. He walks quickly through the empty market square, and then hurries down a side street, his footsteps echoing in the quiet. He doesn’t look back once, and not until he reaches the post house does he stop, place his portmanteau beside him, and adjust the knapsack slung across his back. At this hour, in the small town of Karlsbad, he is the only one there, waiting. His presence goes unmarked by the slumbering inhabitants behind their shuttered windows; around him are empty balconies, darkened buildings, and beyond them a river unseen. It already feels like winter. And if the inclemency of the past few weeks, months even, is anything to go by, tomorrow, too, it will rain. From somewhere, a breeze lifts, brushes past him coldly, and vanishes.

In a few minutes, a post chaise draws up in a great and noisy clatter. The man climbs in, joining three other drowsy passengers, pays his fare, and when asked what name he is known by, answers gruffly, “Möller. Johann Philipp Möller.”

The driver inquires because it is needed for the records, but he casts a second glance at him, noticing the passenger’s soft cloud-gray traveling coat, with its long shoulder cape, topped by a warm velvet collar. Not many of his kind grace this humble coach. Strange, too, that he is alone, without any servants, and with so little luggage. Well, never mind all that. None of his business.

He makes to shut the door, when the traveler speaks. “How long to Egra?”

“Nine hours at most.”

With that he sits back, seemingly satisfied.

“We’re ready to leave, sir.”

“Yes,” the traveler repeats. “We’re ready to leave.”

The chaise makes its swift way southwest, in the darkness, along the fringes of Kaiserwald, the forest looming beside them, prehistoric and immense. By half past eight, they arrive at Zevoda, the day foggy but beautifully calm. The other passengers are awake now—two portly gentlemen, one with a flourishing mustache, and a young man apprenticed to a bookkeeper in Munich—talking about the weather, how they hope that, after so wretched a summer, they should enjoy a fine, dry autumn.

“Look at the sky,” exclaims the traveler in the gray coat. “The upper clouds are streaky and fleecy, while the lower ones are heavy.” He smiles. “This appears to be a good sign, don’t you think?” The others, not wishing to admit how little, to them, this observation portends, amiably agree.

Farther on they travel, descending into the valley. The landscape now alight and green, undulating before their eyes. At noon, they arrive at Egra, lying at the foot of the Fichtel Mountains, under a warm and shining sun. Here they stop for lunch. And although the friendly gentlemen invite him to join them inside the rest house, the traveler declines, and eats his midday meal alone beneath a bright sky.

At two, they continue southward. The passengers doze, despite the rutted road, lulled by goulash and beer, though the man in the gray coat keeps his gaze vigilantly turned outside. He is drinking in the air, the scenery, as though seeing everything for the first, and last, time.

Later, after entering Bavaria, they come at once upon Waldsassen, lying in a cauldron-like hollow in beautiful meadowland, enclosed on all sides by fertile heights. They marvel at the basilica—they do not stop, but take in the view of its Baroque towers, rising splendidly on either side of the narrow arched doorway.

“Is it true?” the young apprentice asks. “About the skeletons.”

“What?” says the mustached gentleman. “That they line the walls of the church?”

The young man nods, looking uneasy.

“The Holy Bodies, they’re called,” adds his companion. “Christian martyrs, exhumed not long ago from the catacombs of Rome.”

“But is it true,” the apprentice insists, “that they’re dressed like royalty? In velvet and silks and jewels?”

The gentlemen confirm this is so.

He shudders. “Is it not macabre?”

The traveler in the gray coat, silent all this while, chuckles. “Perhaps. But if I were them, I’d be greatly displeased.” The other passengers stare at him, befuddled. He continues, “To be happily buried in Rome, the capital of all the world, and then rudely awakened and installed . . . here. Despite being bejeweled for all eternity—what a fall!”

His fellow passengers appear unconvinced. Is Rome truly that wondrous?

“Yes,” he insists. “Yes, it must be so.”

“And have you been to Rome?” they inquire.

“No,” he admits, “not yet. But soon,” he adds, “God willing, soon.”

Well, when he gets there, the others declare, he must write up a report, for God willing or not, they are not planning a journey to the capital of the world anytime at all.

“I shall,” he promises, and they fall into companionable silence.

From Waldsassen begins an excellent road of firm granite, and this, coupled with the gradual descent from the plain, allows them to doze more comfortably—and travel on with welcome rapidity.

They speed onward and are at Tischengreut by five. Here the two gentlemen opt to stay the night. The apprentice and the passenger in the gray coat continue. They are in Weyda by half-past eight, one in the morning at Wernberg, half-past two at Schwarzenfeld, half-past four at Schwandorf, and finally, half-past ten at Regensburg, having covered one hundred and thirteen miles in thirty-nine hours.

They have made good time.

At Regensburg, the traveler in the gray coat books himself into the White Lamb, a pleasant three-storied corner building overlooking the Danube.

“Just you, Herr Möller?” asks the innkeeper.

He, too, steals a quick glance at the expensive clothing.

Him alone, he is informed.

“This way.”

He assigns a lad to help with the scant luggage, up to the third floor, as requested by the guest, for the views. Regensburg is beautifully situated. Outside the window, the medieval town shines in the midday light, with churches upon churches, and monasteries at every turn. Across the river, the suburb of Stadtamhof stands neatly clean and pretty.

It isn’t long before the traveler reemerges onto the streets. He heads away from the noisy market square, bustling with shipping men and vendors, and walks toward the river, the Danube flowing great and wide before him.

There he greets an old woman selling fruit.

“Any grapes or figs?”

“Not yet,” she answers, “you’ll have to head farther south for that.”

“I shall, ma’am, I shall.”

He buys a few pfennigs’ worth of pears instead, and sits on the bank, eating them, like a schoolboy, for all to see. Afterward, he walks through town, stopping at churches and towers, frequently making notes. He drops by the College of the Jesuits, where the pupils are acting in the annual play. He doesn’t stay long; the performance is tragic, unintentionally so.

That evening, he eats an early meal and retires to his room. At the table, he opens up a notebook, and writes: From now, the taste of pears will always be the taste of freedom. How long it has been! Perhaps not since I was a student, and Herder and I roamed around the villages of Strasbourg collecting folktales and folksongs, have I enjoyed such delicious liberty. Alas, too long. Some may cry coward, but I stole out of Karlsbad in secret; they would not have let me go otherwise. They could tell I wanted to get away, and they had in some degree acquired a right to detain me. However, I wasn’t going to be stopped; finally it was time.

The next day, he steps out into a morning that is cool but promises warmth.

Since the post chaise to Munich leaves at noon he ambles through town, stops for a coffee at Café Prinzess. Here he scribbles quickly: It is impossible to express how happy I am, dear one, and what I’m learning every day. Everything speaks to me and shows me its nature. He concludes his morning ramble at Montag’s bookshop, selecting Kant’s Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, a new edition of Linnaeus’s Mantissa Plantarum Altera, and finally, for some light reading, Raspe’s The Surprising Adventures of Baron Munchhausen. At the counter, he waits to pay, while the chatty bookseller tallies up the purchases and makes small talk.

“Where did you say you were from again?”

“Karlsbad.”

The bookseller stops, places his hands on the counter. “Sir, I used to work at Hofmann’s in Jena . . . and I could swear I saw you in there.”

“That would be remarkable!” the traveler exclaims and makes to pick up his purchases, but the bookseller is undeterred.

“I’m quite certain . . . you are Herr von Goethe, are you not? Author of The Sorrows of Young Werther! It is an honor, sir.”

At this, the traveler looks him in the eye. He smiles. “You do me great honor, but I’m afraid you are much mistaken. Now, how much do I owe you for these? I have an appointment to attend shortly.”

The bookseller hesitates, then apologizes. “Of course, sir, pardon me.”

He hands the traveler his change, and watches as he leaves—the bell tinkling gently as the door shuts behind him.

The traveler has not lied. He does indeed have an appointment—a visit to the Schäfferianum Museum. He clutches the books to his chest like a shield, and hurries, keeping his gaze low to the ground.

The museum is located at the residence of Pastor Schäffer, dean of the Protestant parish in Regensburg, also an avid mycologist, entomologist, botanist, and inventor, most recently, of a contraption that washes clothes, while saving on fuel, lye, and water. It is a thing of wonder!

The museum houses the pastor’s rich and extensive personal natural history collection—a cabinet of curiosities that spans shelf after shelf, floor to ceiling. Only here, while gazing at specimens of native Bavarian fungi and freshwater mollusks, several varieties of greenish quartz, the illustrated life history of the Apollo butterfly, and detailed drawings on the anatomy of the water flea, does the traveler begin to relax.

When he meets Pastor Schäffer, large of nose and regal of forehead, he introduces himself as an admirer, adding how he looks forward to perusing his latest publication, a three-volume series on insects found in and around Regensburg. The traveler was familiar already with Pastor Schäffer’s earlier botanical work A Self-Taught Botanist on Expedition: Illustrated with Woodcuts and Drawings, and his richly illustrated four-volume study on fungi.

They chat awhile about the pastor’s current undertakings and then the traveler inquires, with barely concealed excitement, about the correspondence the pastor had maintained with the great Linnaeus, “the biggest influence in my life.”

“Is that so?” remarks the pastor, and confirms that they did indeed exchange letters regularly until Linnaeus’s death a mere eight years ago. How supportive the Swedish philosopher had been! Linnaeus helped the pastor identify insects for his publications, and to expedite his membership of the Royal Society of Sciences at Uppsala.

The benefits were mutual, I’m sure, the traveler says generously.

The pastor makes to object, but admits that Linnaeus had indeed specifically requested his insect illustrations for a new edition of Systema Naturae.

“What an honor!” the traveler declares with a flourish.

They part on friendly terms, the pastor gratified by the interest and attention shown him. “The pleasure was all mine, Herr Möller,” he replies to the thanks he receives for his time.

And the traveler departs with heart uplifted not just by his visit to the museum, but by the thought of all that still lies ahead.

The post chaise fills up, packed with passengers for the big city, and makes haste, driving straight through Abbach, beyond which the Danube breaks against dramatic limestone cliffs as far as Saale, where they arrive at three o’clock. They travel on through the evening and night. As morning seeps across the sky, they arrive in Munich.

Despite the long journey, the traveler isn’t inclined to rest. He heads out from his lodgings and spends the day seeing the sights. From a fruit seller, he buys figs—but they are not yet summer ripe. He lunches at Augustine Brau, where all of Munich seem to be, such is the crowd, and then walks across to the Frauenkirche. He climbs the tower from where a young woman had leaped to her death the previous year, over love gone wrong. She was called, he’d heard, the female Werther. From up there, he hopes to catch a glimpse of the mountains of the Tyrol. But they elude him, swathed as they are in thick mist.

Later that evening, in his room at the Royal Inn, he sits at a desk, writing. I saw people in town who might recognize me—but I enjoy going among them like this, unnoticed and anonymous. Tomorrow it’s straight on to Innsbruck! I’m leaving out a lot along the way but this is in order to carry through the one idea that has almost grown too old in my soul.

For a long while, he stands at the window watching the last of the day’s sunshine catching the cathedral’s towers. Then he walks back to the table and adds: Farewell, dearest one. I think of you all the time.

He doesn’t glimpse the mountains the next morning either, early, when he leaves. The sky is clear but clouds have settled unmoving on the peaks. For a while the chaise travels along the Isar, up above it on alluvial hills of gravel, the work of old high waters. He watches the mist on the river and water meadows dissipate as the day brightens. The other two passengers, husband and wife, complain of the heat, while he looks unperturbed, even quietly delighted. When they stop to rest, he skips about, plucking at plants, sniffing at flowers, exclaiming over stones, pocketing some, tossing others aside.

Quickly, they pass through Benedicktbeuern, nestled in its fertile plain with a broad and high mountain ridge behind it.

“Look!” exclaims the traveler in rising excitement, “they are emerging from the clouds!”

The couple peer at the sky, expecting something biblical, like angels or locusts. “What is?” he is asked.

“The mountains!”

He whips off his hat and waves it energetically out the window.

“What are you doing?” the other two inquire politely.

“I’m saluting them.”

By half past four, they are at the Walchensee, where they stop briefly, for the views and a rest. Before them, the lake fills the valley, still as glass, the water so clear they can see the stones beneath. It is exceptionally quiet. Only the sound of the wind in the tall rushes, and the crunch of footsteps as the traveler walks around, deliberately, casting his eyes to the ground. He plucks several flowers, a sprig of thistle, a single gentian.

“It’s always near water that I find the new plants first,” he mutters. “I wonder why that is . . .”

The other passengers don’t query his actions; perhaps, they whisper to one another, he’s a medicine man. When he’s done, he stands by them, gazing across the lake.

“Do you know,” he says, “the name of this lake comes from a word in High German?”

“Which is?” the man asks.

“Welsche or even Walche. It means ‘strangers.’”

“Strangers?” His wife looks puzzled.

“This is what all Roman and Romanized peoples of the Alps south of Bavaria were called by the locals,” the traveler explains. “Beyond this,” he turns to face the path they’ll be taking, climbing up and through the mountains, “it is a new world.”

On the rocky road south, they soon come across two travelers, walking, a harpist and a young girl, of no more than eleven. The man hails them to a stop.

“Please, good people,” he says. “My daughter is weary from many hours walking. Would you be so kind as to give her a lift a little way?”

Space is made for the girl, and their sparse luggage. The father will walk on and meet her up ahead at an appointed spot. She sits next to the man in the gray coat, perched like a bird, with brown locks and a high delicate forehead.

“Thank you,” she says, “though it isn’t true.”

“What isn’t true?” he asks her.

“That I’m weary. I told father so. I can walk for days and days and never tire.”

“Maybe you have walked that long already, and your father is concerned.”

“Only from Munich this time. Not far.”

“Almost fifty miles, child!”

She looks at him, her chin lifted, her dark brown eyes defiant. “That’s nothing, I tell you.” She rattles off the names of places they have visited, all on foot—Württemberg, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Waldeck, Berlin, and even, she ends grandly, “Einsiedeln. To see the shrine of our lady.”

“And how was that?”

“Crowded.”

“Who did you go with?”

“My mother. We walked all the way together. My mother likes to travel.”

“And you?”

“Yes,” she said simply.

“What do you like about it?”

She looks at him, and with no hesitation says, “My mother tells me if you don’t travel you grow old.”

He laughs, heartily, and then laughs again.

“But it’s true!”

“Yes,” he says quickly, “I agree. Except I don’t think I’ve been to as many places as you.”

She considers this for a moment before declaring, “You still have time.”

“I’m relieved to hear that.”

Outside, the landscape is slowly opening up into a wider valley, the road relieved of the tight press of trees.

“And what have you been to Munich for? Another pilgrimage?”

She shakes her head. She was there, she says, to play the harp for the Elector.

“That’s very impressive!”

The smile she gives the traveler is suddenly sweet and childish. “He enjoyed it greatly, he said, and has given my father many letters of recommendation.” They travel together, performing, from one princely personage to another; so far twenty-one in all. This was how they earned a living. In Munich, they were paid more handsomely than usual, and she was permitted to buy something special for herself.

“What did you get?”

In reply, she reaches for a hatbox near her feet, one she’s placed closest. She holds it on her lap, carefully. Inside is a new bonnet—pale green, her favorite color, she says, edged with snowy ruffles and a white-ribboned bow.

“Oh, that’s pretty!” exclaims the lady opposite.

The girl looks pleased, “Thank you. I chose it myself.”

After she puts it away, she asks the traveler where he is going.

“South,” he replies. “Far south. Farther south than I’ve ever been.”

“Why?”

There’s a long pause before he replies. “Because I am tired of the cold.”

“Oh!” she says, and is immediately distracted. “What’s that?” She points out the window. It’s a tree. “It’s different,” she declares.

He smiles, pleased. “It is. How so?”

She furrows her brow and purses her lips. “Well, the other ones are straight and tall and thin . . . and pointed at the top. This one . . .”

“This one?”

“It’s spread out.” She stretches her arms to either side. “The leaves are bigger.”

“Well done. That’s because it’s a plane tree. The first one I’ve seen on this journey. Do you know what that means?”

She shakes her head, her eyes large.

“It’s getting warmer.”

“Yes. I know,” she says seriously. “My harp told me so.”

“Your harp?” At this point, the couple sitting opposite, who have been mostly dozing, also smile.

She nods her head vigorously. “It tells me about the weather . . . it’s like a . . . a . . .”

“A barometer?”

But she hasn’t heard the word before.

“Never mind, it doesn’t matter. How does your harp tell you about the weather?”

“The strings,” she replies. “If the strings go sharp it means fair weather.”

The traveler says he is pleased to accept that as a good omen.

Soon they arrive at the village where she is meant to be dropped off. He helps her out, and hands her the hatbox. She will wait at an inn for her father to arrive shortly. Her name, she says, is Greta.

“And you?” she asks.

“Johann,” he replies.

She waves him goodbye, and he climbs back into the chaise.

By half-past seven, they are in Mittenwald, where they will rest the night. The day, though, is still bright and warm. As the traveler steps out, the coachman, who’s been whistling a merry tune, attending to the horses, says cheerfully, “Good fortune to you, Herr Möller. Today was the first beautiful day this whole summer.”

The traveler smiles. “And from now, I trust it will go on.”

They leave Mittenwald early next morning. The traveler trains his gaze on the landscape—the nearest slopes dark and covered in spruce, then gray limestone cliffs, and high white peaks against the clear blue of the sky. At every angle the view changes, and for fear of missing something, he keeps himself from dozing.

When they near Inzing the sun is strong and hot. The traveler takes off his overcoat, his long-sleeved jerkin, and puts them away. On they go, toward Innsbruck, lying in a splendid position, in a broad rich valley between high rock walls and mountains. The traveler has a choice: he may stay the night here, or catch another post chaise onward. It’s only noon, there’s much to occupy him here—but he chooses to move on.

The way up gets more and more beautiful. Small settlements, painted white, lie between fields and hedges on high, sloping ground. Water plunges large and roaring down a ravine. Soon he sees the first larches, and near Schönberg, the first pines. He collects a bundle of needles, some pine cones.

It begins to grow dark, the details of the view are lost, while the mountains grow larger and more splendid, and everything shifts like a deep mysterious picture. At half-past seven, they arrive in Brenner, at the foot of the pass that marks the border between Austria and Italy. This, he decides, is where he will rest.

The next day he rises early; there’s much to do.

He sorts his books and papers—choosing what to take and what to discard. He inspects his botanical samples, carefully pressed in a folder.

I’ve acquired a great deal for my creation, he writes, but nothing yet wholly new or unexpected. Also I have been dreaming of the model I’ve been talking about for so long, which might be the only way to give you a clear picture of the thoughts I carry around with me all the time.

At noon, he lunches lightly and quickly, downstairs, and heads back to his room. When he’s almost finished, he leaves aside his packing and stands at the window. The view is dominated by mountains, circling the hamlet, opening up to the sky. He feels himself in a more expansive mood than he has been so far along this journey. Ten days ago, he turned thirty-eight, which is perhaps neither too young nor too old, but how time seems to have spun away from him. Life has been . . . unexpected, with work, with love. So much accomplished, some would say, yet he feels so much remains undone. And—this is not a question he often asks himself—what if he were unequal to the task? Only this journey could make him grow into greater maturity, he is certain, for there are parts of himself he can discover nowhere else but in Italy.

He turns back to the table to write: Up here I look back once more in your direction. From here some streams flow toward Germany, some toward Italy, and these I hope to follow soon. How strange to think that twice already I’ve stood at a similar point—St. Gotthard Pass in Switzerland, June 1775 and September 1779—rested, and not got across. I shall not believe it either till I’m down there. What other people find commonplace and easy, life makes tough for me. Farewell! Think of me at this crucial moment of my life.

Afterward, with daylight still stretching long and empty before him, he strolls out, sketchbook in hand. He perches on a nearby rocky slope, with an aim to draw the hostelry. An hour later, he heads back inside, in a mood less pleasant. The drawing has not turned out to his satisfaction. The shapes, he thinks, are all wrong. He’s no good.

At the doorway, he meets the innkeeper.

“I hope you’ve found everything to your satisfaction here, Herr Möller?”

“Yes, thank you.”

“And you wish to leave tomorrow morning?”

“At the earliest.”

“That’s easily arranged. In fact, if you wish, it could be arranged sooner.”

Oh, says the traveler, how soon?

“Now.”

The innkeeper explains that there is the small matter of him requiring the horses the next morning for another errand—so if Herr Möller is willing, they can drop him to Sterzing and be back by dawn. It works out well, if he doesn’t mind him saying so, for both parties. The traveler, after only a moment’s hesitation, agrees.

Later that evening, as the sun slips behind the mountains, he climbs into a post chaise and heads for Italy.

* * *

On the afternoon of October 29, 1786, in a top-floor room of a modest yet well-appointed hotel near Piazza Navona, the traveler stands by a window—outside is Rome. What a thrill, what a thrill! He can hardly believe it. And as much as he’d like to announce this across the rooftops, he desists, and opts to smile, widely, to himself.

He has spent five weeks in Italy, but has only just arrived the previous night in the first city of the world. The dreams of his youth have come to fruition; the first engravings he remembers—his father hung views of Rome in the hall—he sees now in reality. Everything is just as he imagined. And when he leaves here, he is certain he shall wish he were arriving instead. But no thoughts of departure! So much discovery lies ahead! And this morning, a messenger was dispatched with a note, and the traveler is awaiting the arrival of its recipient imminently.

He feels bolstered, not only by being here, but for how much he has already accomplished. Over the last few weeks, he has come to know and love Venice, the city of water—astounding, the view from the top of St. Mark’s tower, his glimpse of the sea for the first time in his life, how it pounded high against the beach, how he followed its retreat over the lovely threshing floor it left behind. So many places are not just names now—Trento, Verona, Vicenza, Padua. How much better to see something once than to hear about it a thousand times. The sight of blue grapes in the valley around Bolzano. The gigantic cypress in the Giusti Garden. The unforgettable Lago Garda. Palladio’s Renaissance buildings in the big northern cities. And where was it that the crickets sang at sunset? How easily days faded around the edges like a dream . . .

Two things, though, remain most firmly imprinted in his mind.

First, the thrill of hearing in Roveredo, for the first time on his journey, a mix of German and Italian. How happy he was that the beloved language was now going to be the language of everyday use. There, he also bought a new set of clothes and a pair of walking boots, all in the local style, suitably light and less conspicuous. From then on, the traveler blended in, almost a local.

The other, Padua’s botanical garden, with its central, subdivided compartments surrounded by a great circular wall intended to symbolize the world. He has sketched them all—the old chestnut tree, the gigantic plane tree hollowed out by lightning, and inside the greenhouse, the ginkgo with its twin-lobed leaves, a blooming magnolia, and a tall palm planted in 1585—before which he stood in awe, then collected leaves, from the small and simple to the largest fans with spiny stalks.

Although the way here from Venice felt interminable.

If it weren’t for his daily notes, he would remember little of this part of his journey. Cento and its pointed poplars, Bologna, where he ascended the Asinelli tower, and Lugano, from where he wrote, I am at a miserable inn in the company of a worthy papal officer and an Englishman with his so-called sister. In some places, the hostelries were so awful, there was little chance of even spreading out a page. Florence was a blur of an afternoon. He breezed through the Boboli Gardens, the cathedral, the baptistry, and rushed onward. He did notice the olive trees, though, around the city, wild and wonderful. On some evenings, he was outright cold and miserable, trying to warm himself in vain. Still three days to go, I feel as if I’ll never arrive.

But arrive he did.

And here he is, in this small room with a bright fire. He moves away from the window toward its warmth; he’s not cold, but he’d like to sit, he might be a little tired. Where is Tischbein? Surely he must have received his note by now? In his understanding, the neighborhood where the artist resides, near Villa Borghese, is not far. But he could be wrong. He wonders what he will be like—they have been in correspondence for a few years—in fact, thanks to his recommendation, Tischbein is on a grant that allows him to live in Rome—but they have never met. With all the time he’s spent here, three summers or more, the traveler hopes to find in Tischbein a guide—perhaps a friend.

Not long after, there’s a knock at the door. The innkeeper is back, and with him Tischbein. He rises and walks across, both swiftly and with careful measure, glad, curious, smiling.

Tischbein smiles back.

The traveler takes his hand. “Hello,” he says, “I am Goethe.”

“Yes, I know. I mean, it is a great honor.”

Goethe is silent, but still smiling.

“How was your journey?”

“Long, but worth every minute.” At this, he glances out the window. The sky is sharply, pristinely blue, the clouds so white they hurt the eye.

“Rome has been waiting for you,” declares Tischbein.

Goethe laughs, then says, “It is I who have been waiting for Rome.”

“Well, you are now here, and we are very glad for it.”

“It is a change most welcome,” says Goethe. “Up north, the winter is beginning to freeze us over already. I don’t remember the last time I saw the sun in late October. And this year, we’ve also had a wretched summer. Wet and dismal and dull.”

“I have to say I don’t miss it!”

“You will make me call you rude names already!”

They both laugh, and something shifts between them; they like each other, they will be friends. In real life, not just over letters—and anyway, what can one tell over letters, really? Nothing like meeting face-to-face and being in the same city.

“Now,” begins Tischbein, “before I hear all about your adventures, there is a small matter that begs immediate clarification.”

“And what might that be?”

“Your accommodation.”

It is settled before the discussion can even properly begin. “You simply must stay with us,” Tischbein insists, when Goethe says his intention is to spend a month or more in Rome. It is no inconvenience. They are few occupants in a house with a bedroom to spare. He will have space to himself to work, to write. Goethe acquiesces: he will move into 18 Via del Corso the next day.

The setup there is quite perfect, he finds. Smaller, of course, than anywhere else he’s lived in the last decade, back in Weimar. His beloved garden house within Park an der Ilm he has had all to himself, and the house in the center of town, a gift from the duke that he recently moved into, is spacious enough to accommodate several families. The shared apartment on Via del Corso is far from tidy, and the facilities basic, but he walks into it with a lightness he hasn’t felt in years. Perhaps it’s the golden Roman sun, streaming deliciously through the unshuttered windows. Or the sudden sense that time here lies luxuriously before him to do with what he will.

When Tischbein asks how he occupied himself in Weimar, he replies, “I’m a busy civil servant.”

“Are you saying this with gratitude or resentment?”

“Both.”

And it’s true. That was his job, his principal reason for being kept in Weimar, with no lack in material comfort, but his being a writer, a scientist, an artist, seemed to serve as a necessary though glamourous addendum.

Then there was Charlotte. And the entire impossibility of her.

Sometimes what else is there to do besides leave?

He didn’t know what to expect after he sneaked out of Karlsbad—so undramatic an exit, he’d thought. Why hadn’t he needed to chase after the carriage, take a flying leap on to it like a runaway thief? No matter. Perhaps, they were over, the days of such high-spirited shenanigans—carousing with the duke through the streets at dawn, naked swimming in the Ilm, endless flirtations at court parties. At his age, sneaking away without telling a soul was thrilling enough. And even then, some guilt, but what would he have told his friends anyway? That it was time. He had to go. He was off, searching for something, and he hoped, here in Italy, it would all be revealed. They would have laughed, detained him, or worse, teased him. As they had, a few evenings before he left—Faust, Iphigenia, Tasso, they taunted, calling out names of his works in progress, lying for years incomplete.

Goethe is given a room twice removed from the long hall—small but airy, overlooking the busy side street. It has clean, bare walls, and a timbered ceiling set with painted floral decoration in blue and red. He will like waking up here, he’s certain. Perhaps, he dares to think, even with someone by his side.

First, though, the unpacking. He sets out the rock samples he’s collected—limestone from the Apennines, travertine found near Terni—and alongside, he arranges his botanical collection—seeds, drawings, pressings, with pride of place given to a branch from a cypress in the Giusti Garden and the palm leaves from Padua. Then he drags a desk to the window through which he can see, in the distance, a clump of umbrella pines. It’s not a view he’s accustomed to. Around his garden house, he could see green fields, patches of forest, the river, and from his study in the town house, the garden, brimming seasonally with vegetables and flowers. It pleases him, though, to call this his own. Even though, of course, he is sharing the place. Friedrich Bury, a shy, quiet student, is in the room next to his own, and Georg Schütz, a young landscape painter, occupies a tiny corner next to Tischbein’s large spacious studio. Schütz is from Frankfurt, and everyone calls him “Il Barone.”

“Why?” asks Goethe.

Tischbein laughs. “Just like that.”

This is their artists’ colony. And he, of course, is most welcome. They are honored to have him stay.

Domestic affairs at 18 Via del Corso, he finds out, are well in order. The house is kept by a seventy-two-year-old coachman, his wife cooks their meals, and there is a manservant, a maid, and a cat, a fat gray cloud called Callisto.

Arrangements are such that the maid comes in to clean and tidy every day, and the landlady provides them, in the evening, with lit lanterns. She will cook what they like, and fetch groceries for them from the market.

“What do you wish to eat, signore?” she asks Goethe.

“Anything,” he replies happily.

There is also no dearth of options for dining out. This is Rome! The occupants eat out often at a variety of trattoria around town. “We’ll take you to them all,” declares Tischbein. “And show you everything!”

Later that day, Goethe sits at the table to write some letters. The sounds of the street carry up to him, loudly, easily. Back in Weimar even the bark of a dog in the distance served as a disturbance, but he must get used to this, he supposes—the daily hubbub of a bustling metropolis. The plan, among many, after all, is to catch up on his writing. Rework Iphigenia. Complete Faust. Perhaps even begin something new altogether.

Not a thought he could have easily entertained otherwise—between overseeing the silver mines, the roads and army and forestry, running the theater, and most exhausting, navigating the tangled web that was life at court, he just about manages to compose a little poetry now and then.

Why are you in Weimar? his university friends had asked at first, the ones with whom he’d shared visions of a new humanism, a better world. Where should he begin? And would they, or anyone else, understand?

For now, he needs to send news back to the people he’s abandoned. First to his employer, the duke. Forgive my secretiveness and the virtually subterranean journey here. To his other friends he’s more lighthearted, boisterous: Now I’m here and at peace with myself and, it seems, at peace for the whole of my life. For it can well be called the start of a new life when you see with your own eyes the whole thing of which you knew so thoroughly the separate parts. To his mother, joyful. I shall come back a new man and live to my own and my friends’ greater pleasure. To Charlotte, solicitous. I hope they have arrived, my notes and drawings from Venice. I want to go on writing a diary here for you. You are never far from my thoughts, dear one.

Before Tischbein takes him everywhere, he escorts him eight minutes down the road to what he deems the most important locale in Rome.

“The Colosseum?”

No.

“The Vatican?”

Not at all. Caffè Greco. Rome’s artists’ bar.

“Oh? Is it old?”

Twenty years or more. But more important, serving the cheapest wine in the city. They come here almost every evening, Tischbein tells him; it’s where they all meet before usually heading back to Via del Corso for more drinking and art talk. “More drinking than talk,” adds Schütz. It’s a grand place, running the length of the building, a large high-ceilinged room topped by a bright chandelier, a long corridor stuffed with drinking tables, and more booths to the side where one may sit and dine at leisure.

“Signor Gigi,” calls Tischbein when they’re all seated, “tonight, your best.”

“And tomorrow?” answers a smiling, portly man behind the counter, towel flung over one plump shoulder.

“Tomorrow, Signor Gigi, we might all be dead. Which is why every night, we drink your best.”

And so they do. Carafe after carafe of fragrant Frascati. They are joined by Hofrat Reiffenstein, a white-haired, shrewd-eyed diplomat, oldest of them all. The talk around the table mostly concerns their visitor’s time in Rome.

“Where should I start?” asks Goethe. What must he see first? Will the wonders of ancient Rome spontaneously unfold themselves before his eyes?

The others blink. “No,” they say, “probably not.”

“I’ll tell you what,” ventures Reiffenstein. “Don’t start with the Vatican paintings.”

Might he know why?

“If you don’t mind my saying . . . one must earn it.” He gestures with his hand. “One doesn’t just walk into the Raphael rooms or Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel . . . First one undergoes a rigorous training of the eye, and then the pathway opens to appreciate the masters.”

As the evening wears on, Caffè Greco grows more raucous. Other patrons greet Tischbein and his friends, some raise glasses at them from across the room. Before they’re joined by these acquaintances, Goethe makes an urgent plea. He’d like to remain anonymous. Not just for this evening, but for the months to come when he’s in Rome.

“But why?” asks Schütz. “I mean, you’re here now. What’s the need?”

He’d like to lead a completely private existence, Goethe explains, so he may concentrate on art and architecture and any other personal pursuits without being feted as a literary celebrity. Or condemned, as an imperial baron and privy councilor, to an expensive and time-wasting round of visits and receptions.

For this reason, to everyone else, he is Johann Möller.

“Johann Möller?” repeats Reiffenstein.

“If this is your wish, that’s enough for me,” says Tischbein.

Reiffenstein looks across over the rim of his glass. “How will you meet the people you wish to meet? The ones who require letters of introduction . . .”

Goethe shrugs. “I’ll find a way. Or I shall not visit them. I presume there’s more than enough to keep me otherwise occupied in Rome.”

“To Möller!” says Tischbein, raising his glass.

“To Möller!” they all echo, except Reiffenstein.

“You are unhappy with this?” Goethe looks amused.

Reiffenstein bows politely. “I will drink only to you.”

And with that they empty their glasses.

Over the next few weeks, Tischbein is true to his word. Every day it’s a new assemblage of sights to discover. And they walk everywhere.

“It’s the best way,” Tischbein insists, “to get to know the city.”

Goethe is pleased with this, for, he tells his new friends, here in Rome, as he’s been doing recently in his life, he wishes to practice seeing and reading things as they are, slowly, to faithfully let his eye be single, and to continue his complete renunciation of all fixed views. This is the only way to learn the truths of things.

They heartily commend his efforts, but when Schütz asks later what their guest meant by “let his eye be single,” they confess they’re not entirely sure.

“Perhaps he means focused, undistracted?” offers Bury.

Reiffenstein thinks it might be in reference to a passage in the Bible. “Wasn’t it Matthew? ‘If thine eye be single, you are filled with light.’”

The others aren’t fully convinced—“Yes, but what does it mean? And what does it have to do with being a tourist?” Next time, they could just ask.

“The problem,” says Schütz, sighing, “is that I think he expects us to know.”

They are impressed, though, by their visitor’s energy. The days are no longer summer hot, but rainless and still genially warm, and he is out from the early hours until late. Nothing is uninteresting to him—churches and villas, ruins and palaces, gardens and statues, cottages and stables, triumphal arches and columns, fountains and markets. He says delightedly that everything speaks to him and shows him its nature.

In the evenings, they usually come upon the Colosseum, when it is already twilight. Looking at it, all else seems diminished. The edifice is so vast that one cannot hold the image of it in one’s soul: “In memory,” says Goethe, “we think it smaller, and then return to it again to find it every time greater than before.” He bemoans, though, that Rome has no proper botanical garden, unlike Padua, and how this might slow down his botanical studies.

Botanical studies? His friends ask in puzzlement. But you’re a famed author, a renowned poet and playwright, an artist! What’s this about botanical studies?

In these past few years, he admits, botany has grown to be a cherished, all-consuming pursuit. Busily, quietly, he has been occupying himself with nature. It’s true that, until he moved to Weimar a decade ago, he was largely uninterested in plants. He’d lived in cities, Frankfurt, Leipzig, and perhaps his time in Alsace brought him close to the warm, wide Rhenish countryside. But only in Weimar, in the small town, thrust with the sudden responsibility of taking care of the royal parks, was he required to turn his attention to living things.

“Before that,” he says, chuckling, “I might have also been too busy falling in and out of love.” He had little choice then but to observe and learn. It helped that he was surrounded by wooded countryside, and that his garden house stood in the ducal park. “It was here I began to notice—truly notice—the living world around me. I planted a garden with beehives and linden trees, and tended to them through the seasons. I grew interested in the humble kitchen garden . . . It is extraordinary,” he adds with a smile, “how munificent the earth is, how bounteous.” He fed himself, the servants, sometimes even giving his friends fresh treats—tender artichokes, baby potatoes. At the front, he planted flowers—his favorite were rows and rows of red poppies—and every morning in spring, the view from his window changed, with buds coming into flower, flowers wilting, and others rising, shining, their faces open to the sun.

“In all this time, I’ve come to a realization . . .”

“Which is?” they ask.

“That my scientific work will be more important than the bulk of my poetry.”

At this, his friends are amused, though unconvinced. They could easily accept a scientist who wrote poetry, perhaps even a poet who wrote about science, but a poet who is also a scientist? Unlikely. Still, they humor him, and tell him there’s an impressive botanical garden in Palermo, spread over thirty acres by the sea.

Is that so? He’d quite like to see it . . .

“You’ve just arrived,” they tease, “and yet you already speak like you are thinking of leaving! Perhaps it isn’t so steadfast, this love you declare for our city.”

His protestations are incandescent—he speaks of far in the future, naturally, for now his heart is in Rome and only Rome.

* * *

“I have decided to give you a new name, Herr Möller, if you shall have it.”

They are at Reiffenstein’s villa in Frascati, just outside Rome, where they have been invited to stay for a few days. It’s early evening, the landlady has placed the bronzed lamp with its three wicks on the round table, and wished them “felicissima notte.”

Now is the time they gather for their daily art session, a practice for which credit must be given to Philipp Hackert, an artist who lived here not long before but who recently moved to Naples. Now the practice is continued diligently by the diplomat.

“And what might that be?”

“Baron gegen Rondanini über . . . the baron who lives opposite the Rondanini Palace.”

The party burst out laughing. The palace stands exactly where the title suggests. Across from 18 Via del Corso.

“And what about you?” he asks Reiffenstein. “What are you called?”

All the members of their German community have jocular sobriquets. Tischbein is the “twisted-nose phlegmatic.” Hackert is “God’s son, the redeemer of free lunches.”

Reiffenstein laughs. “Tell him.”

“God the Father Almighty,” everyone choruses.

“Exactly. And God the Father Almighty says let us begin.”

They busy themselves presenting the day’s sketches. Bury and Schütz with landscapes, Tischbein a horse grazing, and Goethe a field of maize. During the session, merits are discussed, opinions shared as to whether the objects might have been drawn more favorably, whether their true characters have been caught, and whether all requirements of a general nature that may justly be looked for in a sketch have been fulfilled. “In other words, am I any good at this?” asks Goethe.

In reply comes a raucous clamor: “Not yet.”

That night, Tischbein and his guest go for a walk. The village lies on the side of a hill, or rather of a mountain; and the prospect is unbounded. Rome spreads before them, and beyond it on their left is the sea. Under moonlight, all is dark and silver.

“If I may ask,” begins Tischbein, “why Weimar?”

Goethe laughs a small laugh and says he isn’t the only one who’s wondered.

“I mean,” continues Tischbein, “why leave Frankfurt? Or Strasbourg? Or any other center of culture with Young Werther to your name?”

“Because of that,” says Goethe. “I think I shall spend the rest of my life fleeing that book.” It is a creation, he adds, like the pelican, who feeds his offspring with the blood of his own heart. For the public, nothing he ever writes will match up to what he first wrote. No success can again be as great or as far-reaching. He and Werther are bound inextricably and forever. “Weimar offered a respite. To lead in some ways the unromantic life—I did what Werther would never have done.” Before long, he’d lost sympathy with the Sturm und Drang friends of his youth, who saw nothing revolutionary in being an administrator. “But,” he says simply, “it gives me a steady salary, and allows me to put into practice many things and not just to write about them.” Every place, he adds, gives and takes away.

They are walking along the edges of the garden, venturing not too far out into the open darkness. “And Rome?” asks Tischbein. “What does Rome give you?”

Goethe smiles. “I can only promise you this, that any answer will fall short.” Sometimes a place is more than just a place. It becomes the thing that shines like a beacon, where all your dreams and aspirations are fulfilled. It is that way with him and Rome. Does he see? The beginning and end of all his journeys, the completion of his life’s education. Yet for so long it remained a dot in the distance, receding with the years, ever out of reach. Mired as he was in a web of work and life at court, which kept him from writing, from travel. From all this and more, Rome became also an escape.

“And in this web, is there a lady?”

Goethe doesn’t hesitate before answering, “Yes and no.”

“You mean there used to be and now there isn’t?”

His friend shakes his head. “From the very beginning, it has been both.”

“And when was the beginning?”

This time, he does give pause. “Ten years.”

“My dear Goethe, time enough surely for no to turn into yes, or vice versa . . .”

Time enough, he concurs, for that and a million other things.

They have stopped at a bench, and are resting. The night is quiet around them.

“Her name,” Goethe begins simply, “is Charlotte von Stein.”

They met in the winter of 1776, when he first moved to Weimar at the invitation of Karl August, who had just come of age and been crowned sovereign duke of Saxe-Weimar. “I didn’t quite know what I was doing there to begin with, but there I was. And so was Charlotte.” Older than him by seven years, long married to a country squire, and mother of many children—four of whom had died in infancy. “When I first saw her, I remember thinking she was wounded, that she had composed herself to suffer in order to survive.”

“And had she?”

Goethe nodded. “I think so . . . or at least until we met, and became inseparable.” It was sunshine and shadow, light and dark, a crown of gold and briar. Charlotte was descended from courtiers and born and brought up among them, the embodiment of court values. “It was as though I’d left for Weimar just to find her,” he declares.

For years, she groomed him for court and courtly life. “There never was a day in this decade that I didn’t see her, or write to her, or think of her.” He made himself available to her every whim, her every fancy—constricting his life, slowly, to wrap his company around hers only. He belonged to her wholly, and yet not at all. She offered him not simply a welcome distraction from administrative duties but essential support. He’d drop by every day, for supper at the Stein household. He tutored her children and was especially close to her son Fritz. She had a favorite spot by the river, and in his garden. He even inscribed a verse for her in stone to commemorate her seat.

“I am like the English poet Spenser, writing poetry to the unattainable.”

“So it remained a . . . shall we say . . . strictly spiritual communion?” asks Tischbein.

Goethe nods, purses his lips. “Always.”

Tischbein mutters that he understands now why Goethe needed to escape.

From the start, the “friendship” was public knowledge, and Frau von Stein had no desire to be thought an adulteress.

“And the . . . husband?”

“A complaisant type. A bore. It would be more fun conversing with a doorknob.”

“Yes, I’m sure, but did he not mind this intense friendship?”

Goethe shrugged. “I think he was thankful, and probably thought it good for his wife to have someone to talk to about things that went, frankly, over his head.”

They’ve reached the edge of the garden, where a stream flows, the water so clear it’s almost invisible in the moonlight.

“Sometimes,” says Tischbein, “we are involved in something because we know it has no future.” At this Goethe is quiet. “When we are certain something has no future,” his companion continues, “it is safe.”

“Until . . .” adds Goethe.

“Until?”

“Until safe also begins to mean death.” From somewhere in the trees, an owl hoots gently. “I’m hoping this journey . . .”

“Will revive what’s dead?”

Goethe shakes his head. “Will make way for something that’s alive.”

* * *

They return to Rome a day later, just before a storm that brings rain in torrents amidst thunder and lightning. Then, when the weather clears, it’s as though the storm never happened; it’s bright and warm again, day after day.

Slowly, Goethe falls into a routine—the first few hours of the morning are spent revising Iphigenia, then he’s free to visit the sights, systematically following Winckelmann’s History of the Art of Antiquity, with Tischbein ushering him from place to place. The Pyramid of Cestius, with its brick-faced concrete covered with white marble slabs; the grand Hippodrome of Caracalla, designed for ten thousand spectators; the Palace of the Caesars on the Palatine Hill with its fabulously painted walls; and also, of course, the Vatican.

Here, for a while, they walk about St. Peter’s Square, enjoying the spacious views, eating grapes purchased in the neighborhood. They enter the Sistine Chapel—I could only see and wonder. After they look at the paintings over and over, they leave the sacred building and walk into St. Peter’s Square, receiving from the heavens the loveliest late afternoon light. They sit on the ground, finishing the last of the grapes.

“Tischbein,” says Goethe, “I have a request.”

“Anything.”

“Take me to a garden.”

Of these there are many, scattered in and around the edges of the city.

Their first expedition takes them to Monte Mario, the highest hill in Rome, lying northwest, beyond the Vatican. He has heard about its wild richness, and hires a carriage to drive them to the foot of the hill, and then they walk up slowly. In delight, Goethe stops at cork oaks and Aleppo pines, at bay trees, scrunching and sniffing their leaves. It’s too early for them to be in bloom, he guesses; their small yellow-white flowers will emerge later with warmer weather. Even in the undergrowth, the hairy garlic are yet unadorned with white-flowered umbels. Only bear’s breeches carpet the ground with their thick, vivid green leaves.

They also head to Villa Pamphili, whose grounds are much visited for amusement. Around the villa, they wander through the secret garden enclosure on its south side, the formal parterre with low, clipped hedges that slopes all the way down to the woodlands at the bottom. A large, flat meadow, unfolding before the formal borders of the villa’s garden, is enclosed by long evergreen oaks and lofty pines, and sown with daisies that turn their heads to the sun.

Here Goethe throws himself on all fours, nose close to the ground. “This is what I’m unable to see up north!” The working of a vigorous, unceasing vegetation, unbroken by severe cold. Plant life that’s constantly flourishing because the conditions are perfectly suitable. “There are no buds!” he yelps. Growth is so intense, so rapid, there is little time for this organ of in-betweenness. The strawberry is in bloom at this season, for the second time, while its last fruits are still ripening. The orange trees growing in pots farther up at the balustrades are also in flower, and at the same time bearing both partially and fully ripened fruit.

Occasionally, Goethe plays what Tischbein thinks is a botanical game. He strips a plant of its leaves and carefully lays them on the ground.

“What’s so special about this?” asks Tischbein, bending over to look.

“Nothing and everything.”

It is common groundsel, or as it’s called here, old man in spring. Goethe has arranged the leaves, pinnately lobed like a feather, covered in fine hair, in progression, as they grow on the stem, small to large, and then diminishing again. “Tell me what you see.”

Tischbein shakes his head. “A bunch of leaves.”

“For now, that is enough.”

Toward the end of November, under a too-warm sun, they visit Villa Madama, also on Monte Mario, a structure incomplete but still fine and elegant, with a monumental flight of steps and a terraced garden with views of the Tiber.

They walk among the chestnut trees and firs of the top terrace, and stop to look down over the plant beds, where spring flowers are being planted—cyclamen, crocus, anemones.

“I hadn’t imagined,” says Tischbein, “that your interest in botany ran this deep.”

It didn’t always, admits Goethe. “It began as uncertain reflection, and I still consider my botanical studies uneven and incomplete . . . but it’s true that I’ve been constantly and passionately pursuing them. This is not generally known; still less has it been accorded any attention.”

His friend throws him a quick glance. “Why so?”

“What can I say, Tischbein? Every man to his field.”

The painter sees little wrong in this but he doesn’t say so.

“The world is full of fools,” continues Goethe. “One must be either this or that . . . poet or scientist . . . not both, and not anything more. We must spend our lives inculcating one interest, specializing in one art . . .”

Tischbein hesitates. “Some would say that is the way to true knowledge.”

Goethe snorts. “True knowledge! This division lies only in our minds, Tischbein. Not in the world. The world continues to be exactly as it is.”

Around them, a brutto wind whips up, the southerly sirocco, strongest at noon, often bringing with it quick, short showers.

“I don’t know which is a consequence of which,” says Goethe quietly. “Perhaps they bolster each other . . . this obsession with specialization and the direction that science has recently taken.” When his companion remains silent, he presses on. “Everything is dead. The plants we study, the animals, the rocks beneath our feet, the clouds above us.” He shrugs. “Static. Natura naturata. Nature already created.” But how can this be, he gestures around them, when everything is alive. Natura naturans.

“Natura naturans?” asks Tischbein.

Yes, he says, nature naturing, becoming. “I’ve grown suspicious of the kind of scientific thinking that doesn’t acknowledge this.” Why, botany may be the study of plant life, but plants are treated as inanimate, immutable machines! Back in Weimar, he has friends with great knowledge and experience—Dr. Heinrich, a local apothecary who kept an immense garden of medicinal herbs; Gottlieb Dietrich, part of a family who, for generations, had collected plants and made herbaria. They were tied by their interest in Linnaean botany. They’d head out on excursions together, collecting, identifying, naming, carrying Linnaeus’s Termini Botanici, his Fundamenta Botanica and Philosophia Botanica.

Tischbein admits he hasn’t read any of these.

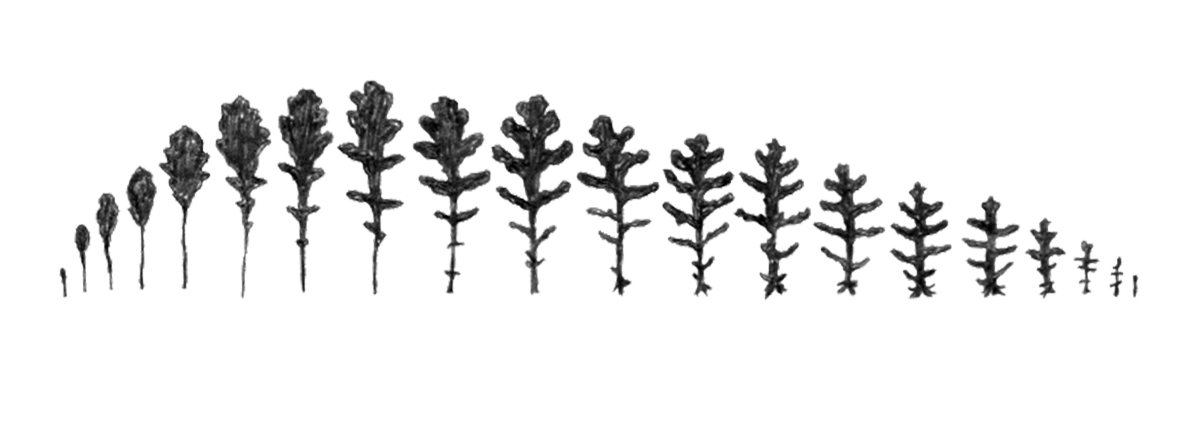

“No matter,” says Goethe cheerfully. “They are about one thing and one thing only: classifying and organizing the natural world, and I will admit in their own way they were useful to me—inspiring me to begin to see, to sharpen my eye, and they were enjoyable too . . . Indeed, some of Linnaeus’s lists I thought read quite like poetry! I was a staunch devotee at the time. Analyzing in minute detail, counting, counting . . . two stamens, three stamens, four . . . naming, labeling, systematically arranging. But to do this is to take away life, Tischbein. Everything is dead,” he repeats. “I discovered that this method lies beyond my nature. What is necessary for comprehensive and intensive systematic work is an aptitude of a special order, which I do not possess. I’ve had to find my own way . . . and I think my journey truly began when I started asking why. Why this particular way, and not any other? Was there anything natural about what was considered natural classification? And more important, was that the only way to learn about plants?” He looks out at the garden, soon to brim over with life. “About this I’ve been thinking more than ever since I’ve been in Italy.”

* * *

At this time, a young writer, Karl Philipp Moritz, also arrives in town, and is a welcome addition to their circle. Goethe is particularly pleased; he enjoys the company of the painters, but here is someone with whom literary discussions may be had.

They begin to meet frequently on walks through the city—talking about Iphigenia, and a new semi-autobiographical novel that Moritz has begun to work on. The young writer was born into poverty, and hasn’t led an easy life, with scant schooling and an assemblage of odd jobs. Goethe finds him deeply perceptive, though, with a sensitive face carved by quiet introspection. Their favorite path lies along the river—with the oaks drooping over the water, shimmering in shades of yellow and green. They stroll here, talking of books and travel and poetry, and one evening, when the sun is sliding low over the horizon, Moritz says, “I haven’t had many occasions to declare so . . . but being here, aren’t we lucky above all else?”

A small hesitation on Goethe’s part before he agrees makes Moritz ask if he feels differently.

“It is nothing,” says Goethe.

“But it isn’t.” Moritz is seven years younger, but endowed with wisdom and sharp observation.

They’ve come to a stop at Ponte Fabricio, and stand on either side of the Quattro Capi. Goethe looks out at the river. “I’m not certain I can explain it. You know how along a journey a traveler’s biggest fear . . .”

“Is not to arrive?”

“Is to arrive and find your enjoyment not measuring up to expectations.”

Moritz turns toward him, the late afternoon sun falling on his face, on the stone, on the water. “Rome isn’t quite what you expected?”

“It’s too simple to say so, and untrue.”

Moritz stays silent, waiting for him to continue.

“I could hardly confess this to Tischbein; it would hurt him so,” he says, hesitating, “but the ruins, the monuments, all this stone, they seem to me lifeless . . . I am trying hard to listen, to hear their voices, but they remain silent.”

They walk away from the river now. Down a crowded main road, stopping to allow a laden cart to pass, and then a carriage.

“Perhaps,” Moritz offers, “enjoyment of a place comes slowly, and one must pass through uncertainty, even disappointment, before appreciating a destination with any depth.”

Goethe nods, yes, there might be something to what he’s saying. For now, he’s happier in the company of green growing things. Even in their quietness they speak to him, as they stand there doing what they must, in their gloriously complex, gloriously simple way.

* * *

For many weeks now, the talk in town has centered around an eruption at Vesuvius, and it sets almost all the visitors here in motion. It seems as if all the treasures of Rome have disappeared: every stranger, without exception, has broken off the current of his contemplations and is hurrying to Naples.

Goethe, too, is keen—what if he were to continue his journey farther south? How tempting it is to stay on in Rome. Yet how tempting it is to leave.

“To wash my soul clean of the image of so many mournful ruins,” he tells Tischbein at Caffè Greco one evening.

“Your flight to Rome will then be a journey to Italy,” says the young artist.

“Yes,” Goethe responds thoughtfully, “it will indeed.”

On their way back to Via del Corso later, Goethe and Tischbein walk awhile in silence.

It is always beautiful in Rome at this hour, and tonight there’s a moon out, the wintry air is sharp and clear, and the buildings edged in silver. It is an hour that coaxes out talk on matters of the heart, and Goethe admits that something has been on his mind.

“All this while,” he says, “I’ve been telling myself it’s too early to be concerned, but I haven’t heard—”

“From Charlotte?” finishes Tischbein.

Goethe nods. “We’re well into December now; it takes sixteen days for letters to get there, maybe a little more back, but that’s enough time for her to have received my letters, even from Rome, and to reply. But nothing.”

Tischbein stays quiet, and then asks, “When you left Karlsbad, and you told no one, did that include her?”

“Yes.” If there had been enough light, Tischbein would have seen the look on his face, one of deep and anguished sorrow. “I had no choice,” he continues unhappily.

“No?” asks his friend.

“The way we were, our days, our lives so intricately enmeshed . . .” Goethe shakes his head. “It would have been impossible. I know she’d have talked me out of it. She has before, and she would have again. What wish do you speak of to spend our lives together, Johann, she would have said, if this is what you do . . . leave me alone for all this time. I’m certain she feels betrayed but what could I do? There was no other way.”

For a moment, Tischbein is quiet. “Perhaps then she hasn’t forgiven you—yet.”

“Perhaps she never will.”

“I’m certain that isn’t true, but—”

“But?”

“You do know this already.”

Goethe nods. “That all will not be as it was.”

They’ve rounded the last corner and are almost home. Beyond, at the end of their road, Piazza del Popolo lies strangely quiet and empty.

“And maybe,” adds Tischbein, “that is something to be desired.”

Later, in bed, Goethe lies awake for a long time. He recounts all the little gifts that were shared between him and Charlotte over the years—the first asparagus from the garden, a framed landscape he’d painted, some pheasant from the hunt, soft milky milchbrötchen from the bakery, and books that were bought for each other and read together. Could she not find it in her heart now to gift him her forgiveness?

* * *

With the arrival of Moritz, Goethe has new company on his botanical walks. Tischbein is pleased, perhaps even secretly relieved, and Goethe, too, for in matters concerning botany he finds the young writer a more interested and perceptive companion.

All through December, they keep up their botanical expeditions with walks out of the city. How few here are the signs of winter: the gardens planted with evergreens; snow nowhere to be seen except on the most distant hills to the north. The citrus trees against the garden walls are now, one after another, covered with protective reeds; but the oranges are allowed to stand in the open. Many hundreds of the finest fruits may be seen hanging on a single tree, which is not, as in Germany, dwarfed and planted in a bucket, but standing in the earth, free and joyous. The oranges are even now very good, but it is thought they will be still finer.

They head out often to the villas on Monte Mario, and after a few such expeditions, Moritz asks, “I notice you return always to the same plants—the laurel tree, this strawberry tree. That shrub . . . viburnum, I think. Why so?”

They’re sitting on the lawn; Moritz has a book in hand, Goethe is sketching.

“You could say,” he says, looking up at his young friend, “I’m attempting to hold a conversation with them.”

“What about?”

“Whatever they wish to tell me,” replies Goethe. He’s trying, he says, to keep what the analytical mind does at bay; its keenness to address, to swiftly determine causal relations—“which can be useful only some of the time”—and in this haste approaches a living plant as an object. What is it? How does it work? These questions are asked immediately, and the answers themselves are usually classificatory in nature.

He holds out his drawing of the viburnum. “A plant is language. Yet all we wish to do is make it speak our own.”

Later, they stroll through the circular court of Villa Madama, around which the formal gardens are arranged. On this fine day, many people have gathered outdoors. They dodge a mayhem of children laughing and running. Then Goethe comes to a stop at a row of bay laurels and gazes into their lush, unresting leafiness.

“Are you,” asks Moritz, “conversing with them?”

“Not yet,” Goethe replies in all seriousness. “I’m thinking: aren’t they each a thing of wonder—all growing things in the world!” He turns to his companion. “Back in my garden house in Weimar, in my study, I placed a potted Bavarian gentian on my table near the window. Every day, I worked and I watched it, but only after a few weeks was it noticeable, how it turned, leaves and stem, toward the light. So I’d alter its position, turn the pot around . . . And a few weeks later, I’d see again that it had changed its orientation.” Goethe looks up at the bay laurels, squinting in the sunlight. “During my botanical studies, Moritz, I’ve come to be suspicious of the notion held by some of our greatest scientists—yes, even beloved Linnaeus—that the world is out there, separate from us. In this way, sadly, we are perfecting what I’ve come to call object thinking.”

Moritz asks him what he means.

“I fear it is the primary emphasis of our culture . . . or it will grow to be, undoubtedly.” He looks around them—taking in the stretch of garden, the line of trees, in the distance the unruly woods. “Object thinking turns all this, our sensuously rich world of living nature, into generalizations, categorizations, abstractions . . . seeing it as no more than a complex mechanistic system composed of physical entities interacting on the basis of impersonal laws. In fact, it takes this notion for granted. Absurd!”

Goethe plucks a bay leaf, then crumples it and holds it up to his nose.

Moritz does the same.

“No doubt this kind of perspective gives us the ability to control and manipulate nature to a great degree. But as a consequence, it causes us to lose our close and immediate experience of the palpable world. In our minds, we are dealing with things out there”—he gestures to the sky—“a world of externality in which we share little or no involvement. We are not participants in the science we practice, the observations we make. I shudder to think of the consequences of this.”

Moritz nods, still holding his leaf.

Goethe points at it. “How does this smell to you?”

Moritz sniffs it again. “Oddly enough, of my mother’s tomato sauce . . .”

“To me, a stuffy university hall in Leipzig filled with graduates wearing laurel wreaths.” He smiles, his eyes shining. “We have rich facilities with which to absorb the world—the gift of our eyes and noses and ears—and yet often we sacrifice all these at the altar of our so-called intellectual mind.” He taps his forehead. Then he steps closer to the laurel tree. The leaves press into his shoulders, his chest. “I think one way to overcome object thinking is to approach a living being as the subject that it is . . . this calls for careful looking, thinking with the mind’s eye, Moritz . . . Anschauung . . . And then, asking one and only one question of any importance.”

“Which is?”

“What do you have to teach me?”

The laurel towers above his head, its leaves waving in the breeze.

“Do you see why, Moritz?”

His friend hesitates. “Because this invites dialogue?”

“Yes!” says Goethe, pleased. “A way by which we strive to stay close to what is being studied, to learn what the plant has to tell us, rather than to impose on it what we already believe.”

Moritz leans closer to the bush. “How does one do this?”

In Goethe’s voice, a tremor of excitement. “If we wish to behold nature in a living way, we must follow her example and make ourselves as mobile and flexible as nature herself.” With this, he detaches himself from the laurel and makes to walk away. Moritz follows.

“We must aspire, my friend,” Goethe continues, “to think like a plant.” By this he does not mean they need to learn how to purify air using the action of the sun. He laughs, pleased with his joke. “Rather, we learn from plants a way of living thinking . . . With my gentian, it struck me how, even in its apparent stillness, it was a dynamically sensitive being, forming and changing itself through dialogue with whatever conditions it met in the world . . . air, moisture, light . . .”

They clatter down the monumental stairs, and take the path that leads to the wooded slopes of Monte Mario.

“To be inspired by plants, Moritz, is to learn to drop fixed ideas, to enter into an open-ended dialogue with the world.” Goethe gazes up at the canopy, raising his arms in a gesture of embrace. “And maybe then, all will be revealed.”

* * *

Amidst all this, the writing.

Goethe isn’t one of those for whom the day is not long enough to do everything. Botanical exploration, sightseeing, dining out—there is time for all this and more, including the revision of Iphigenia. In fact, he is making good progress. The scene at the end, with the two sisters, Electra and Iphigenia, at the altar, reunited just at the point of tragedy, he thinks is especially effective—indeed, if he has succeeded in working it out well, he will have furnished a scene unequaled for grandeur or pathos by any that has yet been produced on stage. He hopes to soon send the manuscript off to Herder, to Goschen, his publisher in Leipzig, and his friends in Weimar.

But midway through the month, his peace is disrupted by a letter.

He finally receives word from Charlotte. It is cold in tone—something he’d expected, but he wasn’t quite prepared for the switch from the intimate “du” to the formal, brisk “Sei.” This is the sharpest stab to his heart, and for a moment he feels a flash of hot anger toward her.

I gave you everything, he begins to scribble, a simple and complete sharing of my life. You have needed my affirmation and I gave it to you—but you desire that it never stop or be diverted elsewhere. I gave up more and more for your sake, living at last in almost complete isolation. I have affirmed your identity by making you the only person who mattered to me. I have done my all to prove this to you, with all the richness and deprivation it brought me: how small my circle of friends, how I lack the consolations of a home and children, and a long . . . Here he stops and tears up the page. The anger is gone, and what’s left is a childish sullenness.

Just when things seemed to be settling, he writes, your letter has broken it all off for me.

His gloom is further deepened by a mishap that takes place before Christmas. In fact, it plunges all their little domestic circle into sad affliction. They spend a day by the sea at Fiumicino, and have a wonderful time—but in the evening, poor Moritz, as he is riding home, breaks his arm, his horse having slipped on the smooth Roman pavement near the Pantheon. He is carried back on a chair to his rooms in Via del Babuino, and there, after a surgeon sets his arm, he remains.

Over the following days, Goethe drops by to see him, bringing little gifts, pastries or fruit or a book or a delightful story. Like the one about Callisto, the cat, who was found, in great excitement by their old landlady, in Goethe’s room, “saying its prayers.”

“What!” Moritz is incredulous.

The cat had sprung up on a table, placed her forefeet on the breast of a cast of the bust of Jupiter, and, stretching her body to its fullest length, was licking his sacred beard. Probably for the grease that had transferred from the mold to the sculpture.

“But I left the good woman to her astonishment,” says Goethe. “She was saying how she’s long observed that the animal has as much sense as a Christian, but this was really a great miracle.”

“Amen.”

Moritz is up and about only in early January. On the day his arm is out of its cast, he is summoned to Via del Corso for a viewing. “A viewing of what?” he asks.

Outside Goethe’s room stands a colossal head of Juno.

It is a plaster copy, he’s told, of the original in Villa Ludovisi. It stands five feet high on a plinth. Goethe is tremendously proud of his outsized acquisition.

“She is my first Roman love,” he declares.

“Hopefully not the last,” teases Tischbein.

To celebrate Juno’s arrival, and Moritz’s recovered health, they head to the Greco for drinks and supper. It is a cool, crisp evening, with the sky turning a deep silvery blue. Against it, the umbrella pines in the Borghese Gardens stand like dark guardians.

After a carafe or two, Tischbein sidles over to Goethe’s side. “I had something to ask of you,” he says. “I’m thinking . . . of painting your portrait.”

“Ah, this is why I’ve noticed you closely scrutinizing me.”

Tischbein nods. “It is true.”

“And how do you wish me to pose?”

“I have a few ideas.”

“Go on.”

“As a traveler.”

Goethe smiles.

“It will be life-size, you’ll be wrapped in a cloak, sitting on an architectural fragment, an obelisk perhaps, and looking toward the ruins of the Campagna di Roma in the background.”

“Well . . .”

“I’ve almost finished the sketch already!”

“What?”

“And stretched the canvas.”

Goethe drains his glass. “Then I happily have no choice.”

“No, you don’t. And if you find yourself a lovely maiden soon enough, we could paint her by your side.”

“Alas, that is not to be fated, my friend.”

“It doesn’t seem fated with the one in the north either, and I say this for . . .”

“My own good, I know. But,” he lowers his voice, “there’s not much choice.”

“My dear Goethe, are you saying Italian women aren’t beautiful enough for you?”

“Don’t be absurd.” He glances at the others, but they’re thankfully engaged in their own discussion. “But I can’t be with women with whom services . . . come at a monetary price.”

“Prostitutes, you mean?” Tischbein grins, making no attempt to lower his voice.

Goethe glares at him. “Yes, that’s what I mean.”

His friend leans in. “Why?”

Goethe shrugs. “I don’t wish to catch anything.”

“That is a fair point.”

“And other unattached women . . .”

“For whom services come free.”

“But they don’t. Marriage is expected in return.”

“That’s Catholicism. And you, dear Goethe, are not Catholic.”

“Indeed not.”

Tischbein raises his glass. “Then we must find you someone married and willing.”

By now, the rest of the party is interested in their conversation.

“Married and willing?” asks Schütz. “What for?”

“To lift the curse of Goethe’s second pillow.”

Most of January is fine and dry, though with a cold north wind that blows through the streets. Soon the rewriting of Iphigenia is complete—i.e., it lies before me on the table in two tolerably concordant copies—and swiftly it is parceled off to Germany.

The new year brings to Goethe a sense of rejuvenation, a sloughing away of the old. He writes to Charlotte hoping for some sort of reconciliation. I’m much improved; I’ve already given up many ideas I was attached to that made me and others unhappy, and I feel much freer. But do now help me too, and meet me halfway with your love . . .