FIRST BLOOD

‘I came about vertically behind the Frenchman, dived down and got ... right on his heels. My machine gun began its monotonous tack-tack-tack. It did not take long before [he] went over onto his left side, emitting smoke ...’1

RUDOLF BERTHOLD

By October 1915, armies on both sides of the Western Front had long been dug into fortified trenches winding some 700 kilometres from Belgian coastal sand dunes in the north to mountain peaks in southeast France. But the stalemate that frustrated ground commanders for over a year did not hamper Oberleutnant [First Lieutenant] Rudolf Berthold, who flew his big two-engine biplane bomber high over British and French troops, easily out of range of soldiers’ guns. Further, he had two gunners on board to help fight off aerial opponents.

The twenty-four-year-old pilot exulted in his advantages of range and height. Writing about his bombing flights over a British barracks complex at Abbeville, France, some thirty-five kilometres east of the English Channel coast, Berthold was pleased that his adversaries must have ‘looked on in amazement when they saw the first German [G-type 2] aeroplane over their encampment …’

‘During the second flight the British soon tried to bring us down, as both of my propellers later showed traces of explosive ammunition … I also flew out over the sea. The broad sheets of water passed big and powerful below me. War and mankind were forgotten there.’3

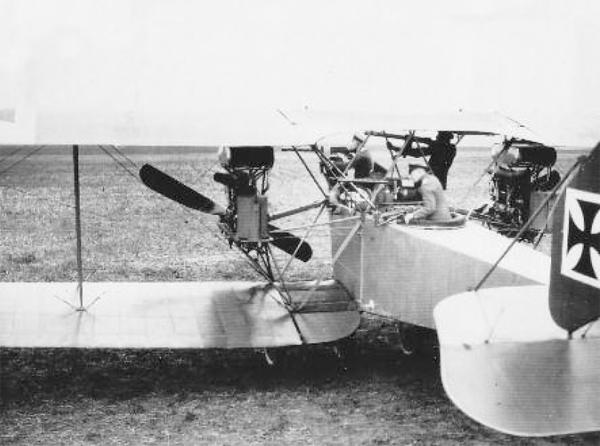

At that time, Berthold flew an AEG G.II,4 which, in the words of one German aviation expert, ‘proved to be … a most efficient bombing aeroplane, easy to fly and maintain and of a robust construction that endeared it to ... hard-working three- to four-man crews.’5 But the bigger AEGs also attracted smaller, faster and more manoeuvrable British and French aircraft whose pilots sought to shoot down the bombers before they dropped their lethal loads – or could return to their bases for more bombs and ammunition.

Combat in the Air

On the bright, clear morning of Saturday, 2 October 1915, Rudolf Berthold and his two observer/gunners headed for Abbeville again, but were interrupted by a British biplane. As the two aeroplanes drew closer Berthold recognised his adversary as a Vickers F.B.5, a rear-engine two-seat fighter aircraft in which the pilot sat behind the operator of a Lewis Mk I machine gun on a flexible pivoted mounting6 that gave it a wide field of forward fire. British flyers called the aeroplane the ‘Vickers Gun Bus’7 for good reason.

A British report for that day described the encounter:

‘Lieut. [Herbert T.] Kemp and Capt. [Cecil W.] Lane of 11 Squadron [were] in a Vickers8 when patrolling north of Arras at 9:45 a.m. at a height of 10,000 feet, [they] observed a hostile machine crossing the line three miles away. Lt. Kemp succeeded in heading off the enemy aeroplane which then turned toward the Vickers and the two machines approached each other [head] on. Capt. Lane opened fire at eighty yards’ range. The hostile aeroplane immediately dived almost under the Vickers and a drum [of machine-gun ammunition] was emptied into it while [it was] diving. The Vickers then dived down after the hostile machine, firing three more drums into it at close range. The hostile aeroplane, which was an Albatross [sic], crossed the line, diving to earth at a very low altitude.’9

The British gunner’s drums each held forty-seven rounds of 0.303-calibre (7.7-mm) ammunition.10 But the cumulative force of the four drums – more than 180 bullets – at such close quarters had a devastating effect on the German bomber. Rudolf Berthold wrote in his diary:

A Vickers F.B.5 of the type that attacked Berthold’s AEG G.II during a bombing mission. (Kilduff Collection)

‘Suddenly I see explosive tracer flashes ahead of our aeroplane. A Vickers pursues us. I would have preferred any other aeroplane to this manoeuvrable little Englishman. Nevertheless, we charge at him! He has seen us and now turns toward us. I know that if it should come to an aerial combat, I will be at a disadvantage as the handling ability of my two-engine bird is inferior. Should I fly away? No! It is preferable to be overcome in combat. After all, I have two observers who know how to shoot.

‘The enemy fires ... and I continually hear the shots hitting our wings. Then, the main fuel tank is smashed to pieces! Shards of fabric flutter from the wings and I make a banking turn. Alongside and behind me I hear my observers firing away. Suddenly, the observer to my right collapses and goes pale, as if he is hit. I realise it is also quiet in the back. I still hear the tack-tack-tack of the enemy’s machine gun. The upper part of my rear observer’s body falls onto the edge of his station.

‘Then both of my engines quit. In one moment the front of my bird is pointing downward. In the next I sideslip, at first downward, then over onto the left wing. The engines howl into life, the wings bow, the aeroplane goes almost straight down. Thank God, I got away from the opponent. Now I hold the control column tightly in my hand and the aeroplane responds to me. At a certain altitude, I pull out slowly.

This view of Berthold’s AEG G.II 26/15 on the ground shows a pilot and three observer/gunners, but he usually flew with only two crewmen. (Tobias Weber)

‘A glance to the rear shows that my observer is alive, he has just blinked his eyes, but the forward gunner is dead. Where to now? To the nearest aeroplane depot, where there is a doctor. How slowly the aeroplane seems to creep along ... Finally we come in to land! I have no idea what happened after that. The following morning, the rear observer died.

‘The [second] dead man was my dear old friend Grüner. I can barely comprehend it; he was not scheduled to fly, but he pleaded with me so earnestly that I could not refuse him.’11

Anatomy of an Air Combat

This encounter needs to be examined, as the preceding account is flawed. First, Berthold’s narratives often conveyed an overblown sense of drama. Second, this text, from Berthold’s Persönliches Kriegstsagebuch [personal diary], seems to have melded the narratives of two fights between his AEG G.II and different Vickers F.B.5 aircraft on separate occasions. The ‘diary’ summarised his activities over time; it did not chronicle daily events.

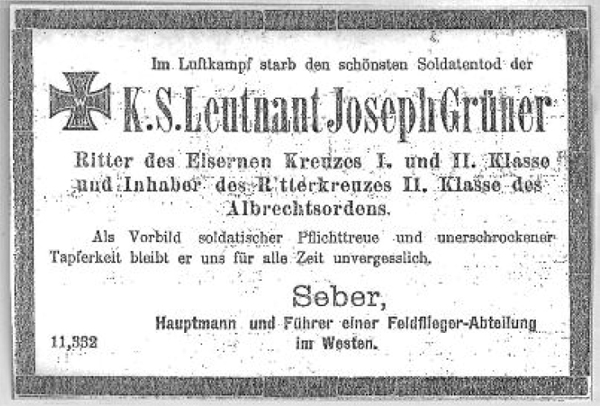

Ltn Josef Grüner, Berthold’s friend and observer/ gunner, who was mortally wounded in the air combat of 6 November 1915. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

In this case, Berthold stated that on the morning of 2 October, ‘the entire region ... lay in a dense coat of fog ... Half an hour later the fog lifted ... and an hour later I was ready to take off. As the fog still lay to the south, we flew in a northerly direction’12 from a German airfield near St. Quentin toward Arras, some sixty kilometres to the northwest. Conversely, a British source reported that the weather for that area was ‘fine all day’.13 And, while Berthold was most likely attacked that day, he escaped from his pursuer. His unit, Feldflieger-Abteilung [Field Flying Section] 23, reported no casualties that day14 – and certainly none related to either of Berthold’s observer/gunners, Leutnants [Second Lieutenants] Josef Grüner or Walter Gnamm.15

But five weeks to the day later, on Saturday, 6 November, Berthold and his crew paid for their incursion over the front lines. On a day when Royal Flying Corps weather officers reported ‘fog and clouds, with observation very difficult’,16 Ltn Grüner was fatally wounded in an air fight north of Péronne. The twenty-two-year-old observer died at Etappen-Flugzeug-Park 2 [Advanced Area Aeroplane Depot 2] at Château de Grand Priel, twenty kilometres east of Péronne.17 German records list Grüner as the only FFA 23 crewman to perish in combat that day18; there is no record of Gnamm19 or any other FFA 23 observer/gunner being wounded.20

A British report for that day noted that a Vickers F.B.5 of 11 Squadron was attacked by what the RFC crew of 2/Lt Robert E.A.W. Hughes Chamberlain and 2/Lt Edward Robinson described as a ‘Fokker biplane with [observer] and machine gun ... north of Péronne’. The pair misidentified their opponent, as, up to this time, the Fokker aircraft company produced only single-seat aircraft; however, other aspects of their account – such as flexible machine guns on the German aircraft – are consistent with features of Rudolf Berthold’s AEG G.II.

Hughes Chamberlain and Robinson stated that they did not see the German aircraft until it was 150 yards away.

‘... It [then] dived from 200 feet above them and opened fire at 100 yards. By the time [we shot at it] the enemy machine crossed in front of the Vickers at fifty yards’ range and in this position twenty-five rounds were fired at it. The [German] then circled left, passing the Vickers at 150 yards’ range, firing from the side in bursts of fifteen to twenty rounds. The remainder of the [Vickers’] first drum was fired into it and, by the time a new drum had been fitted, the range was reduced to twenty-five yards. The Vickers was [approaching] head-on and, at this range, half a drum was fired into the [German], which continued [to respond with] a rapid fire.

‘The enemy then circled ‘round for position to cross the Vickers’ front but, anticipating it, the Vickers fired one drum at the [observer] and pilot at fifty feet. The enemy machine dived steeply, followed by the Vickers and in this position another drum was got off. The [German aeroplane] disappeared in a bolt of clouds at 3,000 feet above Aizecourt ...’22

The last portion of Berthold’s narrative fits the combat described immediately above. Apparently, he managed to disengage from his intended victim over Aizecourt-le-Bas, northeast of Péronne and less than twenty kilometres from the aeroplane depot at Château de Grand Priel. But that short, desperate flight to save his comrade was in vain. Rudolf Berthold had been a reconnaissance and bomber aircraft crewman with FFA 23 since August 191423 and during many long flights over the lines – often with only a rifle or a pistol for self-defence – he had not lost a crewman. It was as if that status represented some mystical bond.

Friendship Forged in Combat

Moreover, Rudolf Berthold and Josef Grüner had much in common, which led to their becoming close friends. Both men were born in villages in northern Bavaria and earned regular army commissions as regimental officer candidates, rather than through the more prestigious Bavarian cadet system. Indeed, they had trained in infantry regiments outside of the Kingdom of Bavaria, Berthold with a Prussian unit residing in a Saxon duchy and Grüner with a regiment in the Kingdom of Saxony.24 Like Berthold, Grüner had been active in the German youth movement and showed strong patriotic feelings.25

Above all else, they shared a craving for battle action that earned them awards for their bravery. Both men earned the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class medals early in the war and Grüner was the first of the pair to receive a high Saxon award. In his case it was the Ritterkreuz II. Klasse des Albrechts Orden mit Schwertern [Knight’s Cross 2nd Class of the Albert Order with Swords], which he received on 15 July 1915.26

FFA 23’s obituary notice for Ltn Josef Grüner included the Prussian and Saxon awards he had earned. (Stadtarchiv Passau)

After Grüner’s death, however, Berthold felt a deep loss and, in a move rare for him, took home leave to mourn his close friend. He did not go to his family for solace; rather he spent time alone, perhaps to wonder whether he had been bold or foolhardy by charging at and flying so close to his adversary. Also, there was the inexplicability of survivor’s guilt: with so many enemy bullets directed at the aeroplane, why had Grüner been hit and not Berthold? He wrote in his diary:

‘I cannot rightly recall what happened in the following weeks. Almost aimlessly I wandered around Germany. Everywhere I looked I saw in my mind’s eye the cockades of the Vickers, I saw my observer hanging over the edge of the aeroplane. All I thought about were vengeance and combat! Sleep soundly, my friend Grüner, you will be avenged!’27

Berthold’s First Aerial Victory

But Rudolf Berthold had to wait more than two months for his triumph. By this time he flew a Fokker E.I Eindecker [monoplane], armed with a fixed Parabellum IMG 08 machine gun28 and synchronised to shoot 7.92-mm ammunition through the propeller arc. This gave it the forward-firing advantage of British and French rear-engine fighter aircraft – with greater speed and manoeuvrability.

A Fokker Eindecker of the type flown by Rudolf Berthold when he achieved his first aerial victory. (Kilduff Collection)

On Wednesday, 2 February 1916, Berthold and Ltn.d.Res Ernst Freiherr [Baron] von Althaus29 attacked a pair of French aeroplanes within German forward lines and shot down both of them. Consequently, Berthold’s ‘kill’, a Voisin LA rear-engine biplane brought down near Chaulnes, was officially credited as his first aerial victory. Althaus’ victim, a Nieuport Type XIV or XV two-seater,30 crashed and burned about fifteen kilometres away, near Biaches, and was recorded as his third victory.31

Berthold’s diary entry that day detailed this momentous event in his military career:

‘The weather was bad today: low clouds, rain. About 3 p.m. came an urgent telephone alert: A big French aeroplane was reported to be over Péronne [almost twenty km away]. Althaus and I were just having coffee, as the others had gone for a walk. Both of us rushed out ... and got right into our “birds”.

‘By this time it was raining again. We tore down the middle of the ’field ... and right into the rain. Althaus was off to my right. We could not see much. Then finally toward the west, over the lines; there was a big hole in the clouds! We flew at 2,000 metres altitude.

‘We were flying in a north-westerly direction, when suddenly I saw two small black spots that swiftly become bigger. They were aeroplanes! I pulled up my bird and took them on. Then they saw Althaus first as he flew lower than me ... I had not been spotted because I placed myself in front of the sun, which had fortuitously come out.

‘What happened now was a few minutes’ work! I came about vertically behind the Frenchman, dived down and got right behind him as he put himself close behind Althaus, right on his heels. My machine gun began its monotonous tack-tack-tack. It did not take long before the Frenchman went over onto his left side, emitting smoke and crashing. I went howling down after him.

‘A glance toward Althaus showed ... his opponent also going down. We had disposed of both of them. Nevertheless, we still had to be aware; one never knows where the next enemy fighter may come from … In fact, once again, my Frenchman righted himself around. Again he fired a burst from his machine gun and then he tumbled down. I saw him disappear behind a small wooded area. At the last moment, I pulled my machine up; otherwise I would have crashed into the woods.

‘There was ...a heavy mist everywhere; it was like looking into a wash basin! Therefore I flew straight and began climbing. I noticed that I was flying very far to the west. From time to time my engine quit, due to either a sticky valve or an oil-fouled sparkplug. I was in a fine mess! Should I land on the other side of the lines? Not for all the world, so I pushed on! At last my engine ran perfectly again.

‘There glistening before me was a silver stripe: the Somme river. Heading off in an easterly direction, I was not far from my airfield. I landed successfully and Althaus was waiting for me at the ’field, he had been worried. Now there were only congratulations and an account of his fight, which was extensive! My mechanics, fine fellows, were beside themselves with joy! We stuck together in happiness and sorrow: pilots, mechanics and “birds”, like a little family.

Voisin LA (serial number V.1321) of Escadrille VB 108 was brought down intact and recorded as Rudolf Berthold’s first victory. (Greg VanWyngarden)

‘Then the report came that our forward-most troops had already confirmed by telephone – the downing of both aeroplanes; they were just behind our frontlines. Half an hour later, cars were heading for them. I did not go with them, as the sight was too depressing. I walked away quietly, but inwardly I was free! My dear friend … Grüner, now you have been avenged!’32