THE FINAL BATTLE

‘Is it not a pity that such men, who risked their lives countless times over the frontlines, must perish in this way?’1

ANONYMOUS WITNESS

It soon became clear to Rudolf Berthold that his precipitous move to regain authority over Jagdgeschwader 2 – so erratic, but so typical for him – had cost him the good-will he had in the higher echelons of the German Luftstreitkräfte. Now he was back in Berlin for medical treatment, but his days as a somewhat indulged, national hero were over. The war was going badly for Germany and his superiors no longer had the time, patience or desire to accommodate his ego.

His sister Franziska, once again composing his diary entries, wrote about this development:

‘Berthold was in the hospital and followed, with growing concern, the affairs at the frontlines and at home. Soon after his last crash he was briefly informed that ... he would be assigned other service within Germany. Nothing further! He had to put part of his life’s work behind him ... He became sad and bitter that they treated him that way and dismissed him so summarily.’2

Berthold was last mentioned in the national press on 13 August 1918, when the widely-read Wolff’schen Telegraph-Bureau news service included his last two aerial victories in that day’s summary.3 A final courtesy from the Luftstreitkräfte came when he was apprised that, on 31 August, command of JG 2 had passed to twenty-five-year-old Oblt Oskar Freiherr von Boenigk, a highly-decorated regular army officer, long-time flyer and twenty-one-victory ace.4 After that, Berthold had to rely on newspaper accounts to learn about the war. Out of a sense of patriotism, news articles of the period tended to magnify Germany’s success and downplay its defeats. Those accounts were generally accurate, but lacked the candour of the battlefront reports to which Berthold was accustomed.

Back to Ditterswind

Rudolf Berthold completed his treatments at Dr. Bier’s clinic in early October. His arm pain was alleviated and he was sent home to his family in Ditterswind to continue his convalescence. Franziska, who remained in Berlin, noted that: ‘in the forest of his homeland, in beautiful Franconia, he gradually regained his inner equilibrium, although he was no longer as physically robust.’5 She made no further mention of his drug addiction.

An old postcard view of Ditterswind shows the pastoral beauty in which Rudolf Berthold tried to find peace at war’s end. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

In any event, Rudolf had not lost his capacity for big dreams – or delusions. On 14 October, he wrote to Franziska:

‘I am eager to get going again! Externally, the consequences of my last crash have been overcome. Unfortunately, my right arm remains paralysed. But in the spring and summer I shot down aeroplanes with it. The will and the skill must still be there! I want to have my Jagdgeschwader 2 once again ...’6

Just over a week later, Berthold was encouraged by a newspaper account about the thirty-fifth aerial victory scored by his protégé Ltn.d.Res Josef Veltjens.7 His joy ceased, however, on reading the 23 October article devoted to US President Woodrow Wilson’s third reply to the German government about peace proposals.8 That news was disastrous to Berthold, who returned to keeping his diary. He wrote:

‘Wilson has responded. We are going on the downward path again. I want to go back out to the frontlines! I sit ... and wait. If only I had my healthy bones – but I can still do it. As long as the battle rages ... everyone with experience belongs out there ...

‘These days I am in the confines of my hometown near Bamberg. It is a beautiful patch of German soil. In the splendid German forest, the solemn spruce trees seem to me to be more melancholy than before – indeed, sad. They mourn with me the weakness and humiliation of our people ...’9

The news of 6 November was more depressing. Reports of mutinies of Imperial Navy forces in Hamburg, Kiel and Lübeck10 led Berthold to compare those uprisings with events in Russia of a year earlier. He wrote:

‘Bolshevism continues to spread ... and, to add the final touch to this measure of shame, the troops are going over in clusters to the revolutionaries. The dress uniform jacket that I wore with pride for so long is now disgraced. How difficult it is, how hard it will be for me to continue to live.’11

A day later, Rudolf Berthold tried to describe the destruction of the old public order and the collapse of the military establishment and civilian support for the kaiser – all social systems to which he remained totally committed:

‘It has happened! Revolution has broken out. Fate, now go your own way! How paralysed the thinking is. Hopefully, the reckoning will come soon for the villains who have used our misery [for their gain]. The kaiser and the princes have been deposed ... The mind cannot grasp how terrible it all is ...’12

The tumultuous events of November 1918 – the Armistice, armed clashes in the streets between German civilians and police – brought with them miserable times for Rudolf Berthold. He admitted to being so sad that, for a while, he could not even pour out his despair to his diary.13 Meanwhile, he also learned that many other military veterans joined private paramilitary units known as Freikorps [free corps], encouraged and supported financially by the central government to counter Arbeiter-und Soldatenräter [Workers’ and Soldiers’ Councils] that were perceived as being in league with the Bolsheviks. There was turmoil in the cities, but in the Bavarian countryside, the hours dragged on for Berthold and, even in the Christmas season, he wrote that the ‘bells ring so sadly, as if they were tolling only to awaken memories of peoples’ woes ...’14

The new year brought reports of street fighting in Berlin involving rifles, machine guns and light artillery. The left-wing ‘Spartakus’ revolutionary movement tried to bring down the government of Social Democrat Chancellor Friedrich Ebert and was finally suppressed on 15 January 1919 by army and Freikorps troops.15

A New Beginning

Despite the turmoil that swept Germany, 1919 seemed to offer hope to Rudolf Berthold. Within the new government in Berlin were many people from the old régime, including people in the new Reichswehr [armed force] who remembered Berthold. Consequently, he was summoned to the German capital for a physical examination to release him from disability leave and qualify him for an aviation-related active duty posting.

A Reichswehr position seemed to be an honourable use of Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold’s professional military training. On 24 February, he was assigned to command Döberitz Airfield on the southeast edge of Berlin.16 Being back in uniform raised his spirits and ‘enabled him to endure any bitterness’.17 Berthold soon had the once bedraggled airfield and its hangars looking like a military facility again. He knew how to motivate men and build such trust that even resentful Workers’ and Soldiers’ Council members worked willingly for him. It was noted that ‘they trusted the one-armed flyer with the Pour le Mérite. His appearance, resolute and brooking no contradiction, impressed them.’18

But that brief idyll came to an end when Berthold was ordered to close the airfield and dismiss the workers. His diary notes that he ‘saw great danger in pushing the destitute and unemployed men into the arms of the Spartakus movement,’19 but he lacked the power to change such a potentially-disastrous social development.

All around him signs, placards and newspaper articles proclaimed ‘Deutschland in Not’ [Germany in peril]. That message became the harshest reality in April 1919, when Munich, the capital of Rudolf Berthold’s Bavarian homeland, was taken over first by socialists and anarchists,20 and then by Communists, who proclaimed a Bavarian ‘soviet republic’.21 Order was restored on 3 May by a combined force of 9,000 Reichswehr troops and 30,000 members of various Freikorps – after fierce street fighting resulted in over 1,700 civilian casualties.22

Berthold Joins the Freikorps

The putsch [coup d’état] in Munich and its subsequent suppression by Freikorps units was a defining moment for Rudolf Berthold. He felt drawn to a form of service he now considered to be higher than that of the Reichswehr and, following his own sense of mission, he joined the Freikorps.23 One of his comrades, Hans Wittmann, wrote:

‘Berthold ... put out a call to patriotic Bavarian youth, especially in the Franconia area, to enlist in the Freikorps unit that was being established not far from Bad Kissingen in the former army training ground in Hammelburg. Enthusiastic young Bavarian men responded in large numbers. Especially numerous was the amount of big, brawny Franconian farmers who reported in ...

‘Within a short time Berthold had at his disposal 1,200 men in a unit that he named the “Fränkisches Bauerndetachement Eiserne Schar Berthold” [Franconian Farmers’ Detachment – the Iron Troop Berthold]. Absolute obedience to the leaders and iron discipline were the foundations of the group.’24

Berthold promised his men hard work in a worthy cause and they responded enthusiastically. They cleaned up the barracks and rehabilitated the old training ground. Unlike regular army soldiers, however, Berthold’s troops ‘did not swear an oath of allegiance and anyone could be let go at the leader’s discretion’.25 But, just as he had led his pre-war youth groups by the force of his strong personality, Berthold continued to inspire his men to want to remain with him in service to Germany.

Berthold’s men completed their training at the end of May and headed south by train for Munich, which already had enough Freikorps units to dissuade any further unrest. The troops were kept busy with long marches and sports activities. Without a purpose in Germany, in early August they answered the call for Freikorps volunteers in the Baltic states to fight Bolsheviks.

Gaunt and weary beyond his twenty-eight years, Berthold posed in his new Freikorps uniform with the identification patch of the Iron Troop Berthold on his left sleeve. Note he tried to conceal his paralysed right hand. (Lance J. Bronnenkant)

Berthold’s men left Munich for a northward journey that ended a month later when they crossed the border into Lithuania.26 There, the Iron Troop Berthold joined the Iron Division, a large, mostly German, volunteer force keeping Red Army forces out of newly-independent Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia. The division, led by Major Josef Bischoff, eventually found itself fighting against local troops that wanted Russian and German forces out of their countries. The conflict was marked by brutality on all sides.

Berthold’s unit, officially the 3rd Company of the 2nd Kurländisches [Courland] Regiment,27 was in combat at Mitau and the Latvian capital, Riga. Berthold’s disability kept him from active fighting, but he rallied and inspired his men as they endured harsh weather and fierce fighting. By the year’s end, a combination of defeats and orders from Berlin – at the request of victorious wartime Allies – to leave the Baltic area and return to Germany led Berthold’s men to a camp on the Lithuanian-German border. There were no honours for the men, only harsh criticism in the German press that reviled them as ‘Baltic criminals’.28 For the moment, though, the Iron Troop Berthold enjoyed the ‘luxury’ of a three-week rest before their return to Germany. Rudolf Berthold knew his unit would be disarmed and disbanded – and possibly further dishonoured29 – and he planned to resist that dissolution.

Commemorative badge of the Iron Troop Berthold Freikorps unit. (Greg VanWyngarden)

On New Year’s Day 1920, Berthold and his men were in the Lithuanian port city of Memel [now Klaipe•da] and feeling much refreshed. He had received orders to proceed by train to Stade, a city on the Elbe river, west of Hamburg, and to remain there pending further directions. Some of his men would have preferred to go south to Bavaria, but Berthold exercised his iron discipline and reinforced that they would go where they were ordered.30 It was an enormous logistical undertaking to move all the men and equipment of the Iron Division, which had not yet been ordered to disband, and this only added to a general public nervousness.

Return to Germany

Finally, Berthold’s unit moved to locations in the area near Stade. The presence of Freikorps units so close to the city created a delicate situation at a time when neighbouring communities had varying allegiances. People in conservative communities wanted to restore the old social order; those of a liberal persuasion wanted a fully-democratic society. There was great fear of a right-wing military-backed putsch in Berlin. Such anxiety was stoked when it became known that Berthold’s unit had been ordered to proceed to a military campsite at Zossen, just south of Berlin, to be demobilised on 15 March. That location was already home to the 6,000-man 3rd Marine-Brigade,31 commanded by Korvettenkapitän [Lieutenant-Commander] Hermann Ehrhardt, a fervent nationalist and a Freikorps founder.

Initially, officials in Stade requested that Berthold’s men be disarmed. As an expression of good faith, he agreed to turn over ‘a portion’ of the unit’s weapons to the local armoury.32 Then, on the morning of Saturday, 13 March 1920, it was the Iron Troop’s time to head for Zossen. Berthold ordered his force – now down to some 800 men, equipped with 300 rifles and a few machine guns33 – to form up for the eighteen-kilometre march from their camp in Drochtersen to Stade. They would travel the rest of the way to Zossen by train.

On their arrival in Stade, however, Berthold and his men learned that a military-backed putsch had been launched in Berlin against the government of Chancellor Friedrich Ebert. Now it became imperative for Berthold to reach Zossen. He claimed to want no role in the insurrection, even though he acknowledged being responsible to General Walther Freiherr von Lüttwitz, Reichswehr commander in Berlin and one of the putsch leaders.34

At this point, Germany teetered on the brink of civil war, as General von Lüttwitz and political right-wing activist Wolfgang Kapp called for order to be maintained by Reichswehr and Freikorps units. Chancellor Ebert countered by urging Germany’s workers to launch a general strike to thwart the take-over. When Berthold’s men tried to board the train, they felt the sting of the strike, as the train crew at Stade refused to get under way. Berthold then ordered his men to occupy the city’s post office, telegraph office, city hall and train station; and they spent the night in the local girl’s high school.35

The following day, Berthold was determined to use the train to move his men and equipment to Zossen. His comrade Hans Wittmann summarised the next course of action: ‘Therefore, the watchword for us became “help yourself!”’36 And the Iron Troop, which had already voted to support the putsch, took over the train and forced the crew to transport them and their equipment eastward. In response, other striking railroad workers turned off all signal lights on the rail line, requiring the train to proceed slowly and cautiously to avoid a collision on the rails. It was dark when the commandeered train rolled into the small community of Harburg, southeast of Hamburg, at about 9:00 on Sunday night. Berthold ordered the train to halt.

Town officials in Harburg, alerted that Berthold’s unit was heading their way, arrested the commander of Pionier-Bataillon 9 [combat engineer battalion], to neutralise his 900 Reichswehr troops.37 Harburg was governed by Independent Socialists, who were bent on obstructing Berthold’s plans, and were prepared to use their own armed force to do so. When Berthold met with town officials, he was assured his troops could be housed safely in the Heimfelder Middle School, its residence facilities and adjacent buildings in the Woellmerstrasse – but that assurance was a ruse.

Clash in the Streets

By the following morning, Harburg was on high alert. Local trade union leaders tried to motivate the resident Reichswehr soldiers to convince Berthold to disarm his men and leave peacefully.38 But the soldiers were wary of disobeying orders of their officers, who supported the putsch. Labour leaders then armed their own men to face the battle-hardened Freikorps members.

Berthold overplayed his hand and stubbornly refused Harburg Oberbürgermeister [Lord Mayor] Heinrich Denicke’s offer of safe passage. By noon on Monday, 15 March, groups of armed workers approached the school area. There are several versions of what happened next, but all agree that Berthold’s men demanded the crowd clear a path in front of the school – and sent a burst of machine-gun fire over the heads of the civilians. Instead of being frightened off, men in the crowd returned fire and Berthold’s men withdrew into the school buildings. The citizens militia encircled the school area and many shots were exchanged, eventually resulting in fatalities on both sides: ‘Thirteen civilians and eleven military personnel, of whom three fell in actual fighting, the remainder were murdered after being disarmed.’39

The stand-off lasted into the late afternoon. With little ammunition left, Berthold ordered a white flag be shown and called on the mayor for further negotiations. Denicke and other town leaders steadfastly offered only assurance of safe passage back to Stade for all Freikorps members who were disarmed. Realising he was defeated, Berthold gave in. Then, at about 6:00 p.m., as Berthold’s men began to file out of the school buildings, the crowd – not part of the negotiations and now outraged at the sight of their own dead – attacked the Freikorps men. More shots rang out.40

Berthold and some of his men sought refuge back inside the main school building. By one account, Berthold escaped through a back door and moved safely down a side street when a civilian spotted the Pour le Mérite medal around his neck and called out to his comrades. An angry mob chased Berthold down and, as he disappeared from sight, more shots were heard. It was reported that, with his one good arm, Berthold pulled out a pistol to defend himself, but lost it in the struggle and was shot with his own sidearm.41

When Hans Wittmann arrived at the spot, as he later wrote, he saw only:

‘In the dirt of the street lay, lifeless, Hauptmann Berthold, his shoes and his overcoat robbed from him, his face crushed into a formless mass by the mob’s feet, his paralysed arm torn out of its socket, his bloody body punctured by gunshot wounds ...’42

The putsch in Berlin ended the following day and, when cooler heads prevailed in Harburg, the unarmed Iron Troop men were taken to an area military base. Berthold’s body was removed to a hospital in Wandsbek, a suburb of Hamburg, where an autopsy confirmed that he died from gunshot wounds – two to the head and four to the chest.43 Upon learning of Berthold’s death, two old flying comrades in nearby Hamburg, former Leutnants Lohmann and Tiedje, rushed to the hospital.44 They awaited the arrival of Franziska Berthold, who confirmed she was travelling from Berlin to claim her brother’s remains and personal effects. Meanwhile, decorations stolen from Berthold’s corpse – his Pour le Mérite, Iron Cross 1st Class and pilot’s badge – were retrieved from a rubbish heap at an ironworks in Harburg.45

Another Funeral in Berlin

Friends and former comrades gathered first at a chapel in the Wandsbek hospital, while arrangements were made for Berthold’s funeral to be held in Berlin. In addition to helping plan that ceremony, Lohmann and Tiedje negotiated for Berthold’s men to be released from Harburg46 to a more friendly Reichswehr facility in Altona, closer to Hamburg. Then they proceeded to Berlin, where, despite the collapse of the putsch, people remained wary of events involving armed uniformed men.

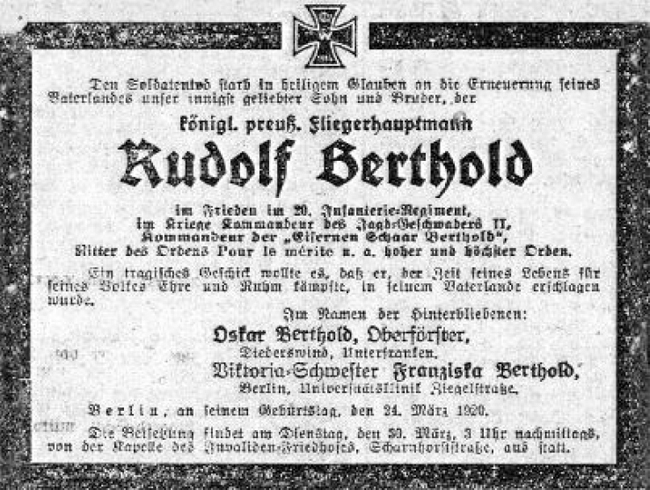

The Berthold family announced Rudolf’s death and funeral arrangements in this Berlin newspaper obituary. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

Thus, at about 3:00 p.m. on Tuesday, 30 March – six days after what would have been Rudolf Berthold’s twenty-ninth birthday47 – he was buried in the Invalidenfriedhof, the national heroes’ cemetery. Protocol called for his pall bearers to be of Berthold’s rank, but his family requested that members of his cortège be sergeants from his Iron Troop.48 His wish to be buried with his comrades49 was honoured and his remains now lie in a triangular arrangement next to the grave of onetime JG 2 pilot Ltn Oliver Freiherr von Beaulieu-Maconnay, whose plot abuts that of Berthold’s best friend, Hptm.d.Res Hans Joachim Buddecke.50

Many long speeches were made over Berthold’s grave, but a simpler tribute came from an anonymous woman from Bremen who was in Harburg during the street battle. She wrote to a friend in Erlangen:

‘Berthold was killed in the fighting. You will read about it in the newspaper. Is it not a pity that such men who risked their lives countless times over the frontlines must perish in this way?’51

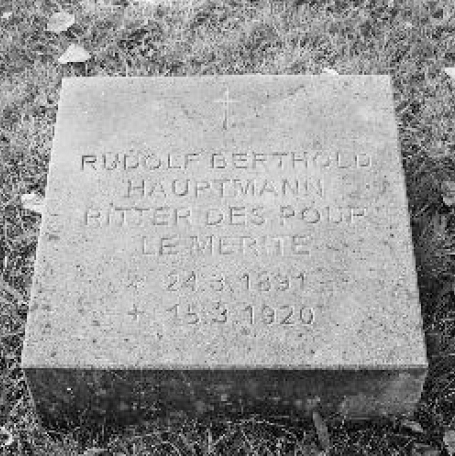

Originally, Berthold’s grave had an ornate cover decorated with his flying sword insignia and a Pour le Mérite likeness. Reportedly, it disappeared about a year before the infamous Berlin Wall was erected around the eastern part of the city. (Lance J. Bronnenkant)

Responding to complaints that Rudolf Berthold had been the victim of lynch mob justice, police in Stade investigated the events of 15 March 1920. The following February, two men were charged with murder: Johannes Bremer, a thirty-six-year-old coppersmith from Harburg, and forty-year-old fishmonger Otto Noack from Hamburg.52 Both men were put on trial and were acquitted. Bremer later gained a minor post in the local Social Democratic Party. After Adolf Hitler’s National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP) came to power in 1932, Bremer was arrested and spent time in several jails. He ended up in Buchenwald concentration camp, where, on 1 December 1937, he was killed while reportedly attempting to escape.53

Now, Berthold’s grave is marked by a small stone monument. (Kilduff Collection)

Even though Rudolf Berthold held conservative views and favoured a restoration of the monarchy – which was anathema to the NSDAP – his life and achievements were lionised during the Third Reich period. He was touted as a nationalist hero, whose sacrifices were held up as worthy of emulation. Various cities named streets in his honour. Two noteworthy examples are Rudolf-Berthold-Strasse in Bamberg, where he attended school, and Hauptmann-Berthold-Strasse in Wittenberg, where he joined the army. After World War II, however, the streets were renamed.

Berthold’s historical legacy suffered a further blow in 1960. Officials in, then, Communist-dominated East Berlin altered the Invalidenfriedhof, which straddled its border with West Berlin. The eastern government ‘cleared’ many of the historic gravesites on its side to reinforce its defences by gaining an unobstructed view of the border. Thus, Rudolf Berthold’s plot lost its once ornate gravestone, which has not been recovered. Four years after Germany was reunified, in 2003, independent donors paid for Berthold’s grave to be restored and for a modest stone grave marker to be erected there.

Perhaps Rudolf Berthold – the tempestuous Iron Man of early German fighter aviation – has finally found the peace that eluded him in life.