PISTOLS TO MACHINE GUNS

‘I view the aeroplane ... as a living thing that must be as one with me. Only he who handles his the way a rider handles his horse would have such ... a bond with his bird that he would never feel so close to it as he does when he leaves the ground and roars over the countryside.’1

RUDOLF BERTHOLD

In October 1914, the area around Etappen-Flugzeug-Park 2 was an island of relative tranquillity amidst the war raging at the frontlines. The men at EFP 2 felt secure behind a barrier of fortifications, artillery and ground troops – and under the leadership of an outstanding pre-war military aviator, Hauptmann Normand Knackfuss.2 To the men at the park, the thunder of artillery fire some twenty-five kilometres to the west was a minor distraction to the activities of their daily lives. Thus, Rudolf Berthold was able to complete his pilot training quickly and uninterrupted. An entry in his diary reflected the positive developments:

‘Fortunately, I was assigned to be instructed by one of our earliest peacetime flyers, Ernst Schlegel.3 His greatest quality was that he … tried to get into the innermost thoughts of his pupils in the aeroplane ... I have Schlegel to thank that I view the aeroplane not as an unfeeling, dead heap; but, rather, at all times as a living thing that must be as one with me.

‘Only he who handles his aeroplane the way a rider handles his horse would have such ... a bond with his bird that he would never feel so close to it as he does when he leaves the ground and roars over the countryside. He who works the control column with a rough hand will never fully be in the soul of the aeroplane and trust it. That is really the first prerequisite for a good flyer.’4

While at EFP 2, Rudolf Berthold became friends with twenty-four-year-old Leutnant der Reserve [Second Lieutenant, Reserve] Hans Joachim Buddecke, who had learned to fly in the USA and returned to Germany after the war began. Buddecke5 had been commissioned in the Leibgarde-Infanterie-Regiment (1. Grossherzoglich Hessisches) Nr. 11 5 – one of the oldest regiments in the German army6 – but, rather than return to that unit, he was qualifying as a military pilot. He confided to Berthold that he had ‘problems’ with his commanding officer, Hptm Alfred Keller7 of Feldflieger-Abteilung 27.

Keller forbade Buddecke from practicing tight turns and other aggressive air combat manoeuvres, and refused his request to fly a monoplane fighter aircraft.8 Hence, Buddecke asked Berthold to urge Hptm Vogel von Falckenstein to request him for FFA 23. Berthold did not have to work hard to persuade his superior to accept such an experienced pilot as Buddecke.

Berthold wrote in his diary:

Staff and student pilots at Etappen-Flugzeug-Park 2 enjoyed the amenities at Château de Grand Priel. Attendees at a pleasant weekend outing were, in the top row, Hptm Normand Knackfuss (fourth from left) and Ltn Rudolf Berthold (sitting on the banister). In the lower row, Ltn.d.Res Hans Joachim Buddecke (far right) and (second from right) an unidentified observer from FFA 32. (Tobias Weber)

‘Of all the comrades [at EFP 2], Buddecke is the closest to me. Loyal and sincere, he is a daredevil to the point of recklessness; tenacious and with no consideration for himself, yet he is also full of empathy and is so modest. We have at all times stuck together and will remain good friends in the future.’9

Just as friendship bonded Berthold to Buddecke, admiration linked him to his civilian flight instructor Ernst Schlegel, about whom he wrote:

‘Only a few ... flights with Schlegel were enough to inspire me with trust for my aeroplane. One day I just flew alone. It was so obvious that I did not feel any insecurity for even a moment; on the contrary, I was never so proud and happy as I was on the day of my first solo flight. After the first smooth landing, I would have preferred to continue flying if Schlegel, exercising his authority, had not stopped me ...

‘In rapid succession ... I flew all of the aircraft types that were then in use at the frontlines. In early January 1915, I reported to my abteilung that from this time forward I would like to be deployed as a pilot.

‘Shortly before my return to the abteilung, Schlegel became ill and I had to take over for him in performing acceptance flight tests of new machines [arriving at EFP 2]. How proud I was that such trust was placed in my flying skill ... furthermore, test flying the machines offered the great advantage of further improving my training. By dismantling new machines one may encounter one or two little flaws that would otherwise hardly be noticed ... If one overlooks the smallest flaws, then the aeroplane will crash. For me, these testing flights were the best way to probe the airworthiness of the aeroplane ...’10

Pre-war pilot Ernst Schlegel (left) presented this signed photo to Rudolf Berthold (right) as a memento of their flying experiences at EFP 2. (Greg VanWyngarden)

Berthold was anxious to return to his unit, but he departed from EFP 2 with conflicted feelings about the war. He confided to his diary:

‘Yes, it was a beautiful time ... at the Flugpark! No discord ever disturbed our being together; our comrades were all happy, yet serious-minded... [and] we passed many carefree hours together. How cosy it was to sit by the big officers’ mess window after lunch ...

‘During the evenings, from time to time, we took a little stroll to St. Quentin; we also wanted to see people again. Here and there in passing one caught a fiery glance – mostly filled with hatred – from a pretty little French woman … And, evidently, that is how we were viewed by some of the inhabitants, as nothing more than feared “barbarians” ...

‘There we were joyously happy for the moment. Perhaps one would be dead in the morning. That was the emotional relationship between seriousness and joy, between duty and freedom; both righteous, both understanding.’11

A Leader Falls

Sunday, 10 January, 1915 started out as a marvellous day for Rudolf Berthold. He had fulfilled his qualifications at Château de Grand Priel and headed back to FFA 23 to complete a few final requirements for the Militär-Flugzeugführer-Abzeichen [military pilot’s badge],12 which would be a proud addition to his uniform. But, as he wrote, the day turned out to be dreadful:

‘How I looked forward to rejoining my old abteilung. Instead, the return was one of the hardest days of my life. For, our leader, Hptm Vogel von Falckenstein, to whom I was loyally devoted, had not returned from a combat mission on the day I arrived … After that, it always seemed to me that I had to search for him. My only thought was how to wipe his loss out of my mind. I flew and worked until I was so tired that I collapsed, and then struggled to my feet again with one thought always in mind: “He did not return from a combat mission.”’13

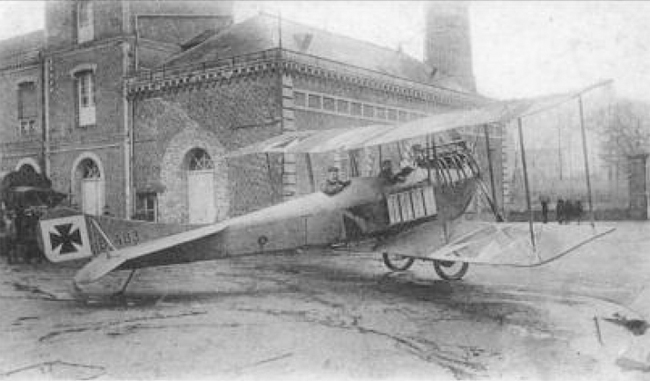

Upon Rudolf Berthold’s return from EFP 2 he learned that Hptm Otto Freiherr Vogel von Falckenstein had been forced down and killed in this aircraft, Rumpler B.I 483/14. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

Fierce ground fighting had taken place that morning as German forces defended their positions at La Boisselle, northeast of Albert,14 in the Somme sector. FFA 23 was ordered to provide aerial reconnaissance of the area. Serving as observer this time, Hptm Vogel von Falckenstein undertook the mission in a new biplane, Rumpler B.I 483/14. His pilot was a man new to the abteilung, Oblt Franz Keller.15

The German flyers’ mission took them over French territory, west of Albert, where they were spotted by the crew of a two-seat French Morane-Saulnier Type L high-wing monoplane. The two aircraft were evenly matched in terms of firepower – the Rumpler’s observer was armed with a rifle16 and his French counterpart with a carbine17, but the latter had an advantage: the pilot, Sergent Eugène Gilbert,18 was a seasoned pre-war flyer who, by this time, had already participated in downing two German aircraft.

Gilbert and his observer, Lieutenant Alphonse Bros de Puechredon, closed in to do battle. Gilbert manoeuvred into a favourable position and his observer fired shots that forced their adversaries to land at Rainneville, southeast of Villers-Bocage. The German pilot was wounded and taken prisoner; his observer had been killed.19

FFA 23’s Hptm Vogel von Falckenstein and Oblt Franz Keller were brought down by a Morane-Saulnier Type L monoplane of the kind seen here. (Volker Koos)

A French account of the 10 January aerial combat, filed by the Reuters news agency, appeared later in the month in Germany:

‘No doubt with the intention of ramming his adversary, the German flyer turned his aeroplane and fired in a direct line at the Frenchmen. A sharp turn saved the latter from the, apparently inevitable, catastrophe. The French observer now fired four well-aimed shots.

‘The first bullet hit the German observer Captain von Falckenstein in the heart, the second smashed the upper arm of the pilot, the third wounded him in the neck and the fourth penetrated the radiator of the engine. Despite his severe wounds, the pilot succeeded in bringing his machine to the ground intact. The landing of both machines occurred within French lines ...

‘And what happened next was a scene that made an unforgettable impression on the men looking on: slowly the German pilot climbed out of his machine, approached and offered his uninjured hand to the French observer and said in flawless French: “Although the battle turned out to be not in our favour, I am still proud to have duelled with so worthy an adversary.”’20

While the German pilot’s gallant tribute to the French crew may have been true, it was among a number of early World War I aviation-related anecdotes that gave rise to a myth that combat airmen on both sides were members of an élite flying fraternity that was bound by a chivalric code of honour. In fact, most combat flyers, including Rudolf Berthold, understood warfare and were intent on destroying their enemies.

Vogel von Falckenstein was succeeded in command of FFA 23 by thirty-one-year-old Hptm Karl Seber,21 who had reported to the unit in October 1914, while Rudolf Berthold was back in Germany, taking delivery of a new aeroplane. Seber quickly established himself as a tenacious aerial combatant. During one mission, he and his pilot, Oblt Gottfried Glaeser, dropped bombs on the rail yard at Amiens and apparently shot down a French two-seater. Although they may not have been victorious, as there was no corresponding French casualty,22 the following July, Seber and Glaeser were honoured for their actions during that fight.

Hptm Karl Seber, an observer and FFA 23’s second commanding officer, later helped to found the Finnish Air Force. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

They received the Kingdom of Saxony’s Ritterkreuz des Militär-St.-Heinrichs-Orden [Knight’s Cross of the Military St. Henry Order], the first of four steps in a series of honours that comprised the highest Saxon bravery award (which was also the oldest military order of all the German states).23 Seber’s citation for the award makes an interesting, but inaccurate, Saxon claim to the unit:

‘Leader of the Royal Saxon Feldflieger-Abteilung 23 ... Hptm Seber performed heroically as an observer on many occasions. He carried out an especially gallant act on 18 November 1914, when, with Oblt Glaeser, he forced down a superior French aeroplane with shots from a pistol on their return from Amiens.’24

A Pilot at Last

Meanwhile, on Monday, 18 January 1915, Rudolf Berthold completed his flying qualifications, which included a flight over the frontlines. Once again, his personal sense of mission prevailed when he described that accomplishment:

‘I am a pilot! Yesterday, I passed the final test. As of today I wear the Militär-Flugzeugführer-Abzeichen! Finally, I have attained what I had strived for in peacetime. Now I am a fully-qualified flyer, independent of the will of another person in the aeroplane. There are good reasons why I pressed on to become a pilot … Over the course of time my activities as an observer did not completely satisfy me. It was just as if I were only flying for fun. Also, my pilot did not suit me at all … Now it has turned out well: I feel like a victor, so inwardly liberated!’25

Now in control – rather than in charge – of the aeroplane, Berthold could be more aggressive during combat flights and perhaps even use his hand-held sidearm to help bring down an opponent. FFA 23’s old aeroplanes had been replaced by much better Rumpler B.I and Albatros B.II biplanes. Berthold was familiar with the latter, having flown them with his flight instructor, Ernst Schlegel, and he was happy to have been assigned one. To further improve the situation, in mid-February, Berthold was paired with an eager and energetic observer, Ltn Josef Grüner.

After the French report of Hptm Vogel von Falckenstein’s death became public knowledge, Berthold was certain that he had seen the French pilot responsible. He meant to avenge his former commanding officer, as he noted in his diary:

‘A French monoplane often crosses over Amiens. I know the fellow well, as my Abteilungsführer was his victim. Woe unto him if he comes in front of my pistol!

FFA 23 airmen posed for this view with a new aeroplane. Standing are (from left): Ltn Trentepohl, pilot; Ltn Hans-Joachim Freiherr von Seydlitz-Gerstenberg, pilot; Oblt Franz André Paul Souchay, observer; Hptm Karl Seber, abteilung leader; unknown; Hptm Eberhard Bohnstedt, observer; Oblt Fritz Böhmer; Ltn.d.R Anton Hirsemann, observer; Oblt Friedrich Schueler van Krieken, observer; and Ltn.d.Res Erwin Tütschulte, pilot. Seated are (from left): Ltn Walter Gnamm, observer, and Ltn Rudolf Berthold, pilot – others unknown. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

I challenge him almost daily. He always appears quite suddenly, soon sits behind me or close above my aeroplane so that I cannot see his face.

‘As we still do not have machine guns in our aeroplanes – only rifles and pistols have been issued – I prefer to rely on making aerial manoeuvres until I have him at a disadvantage. One time I succeeded in flying right above him. I shouted to my observer: “Shoot him!” The shot thundered. The other observer threw his hands into the air and the French machine went straight down. But, as it turned out, we had not hit the aeroplane.’26

Following the French and British counter-attack along the Marne in September 1914 and the advent of static trench warfare, German forces concentrated on outflanking the Allies’ northern wing. Thus, there was heavier fighting in Flanders, much to Berthold’s disappointment, as seen in his comments about lighter activity in April and May 1915:

‘In recent months the frontlines have been, and are still, fairly quiet. The flyers’ reports are almost always the same. Opposite Paris, nothing had changed. We photographed much of the area. Often, I flew over enemy territory, with the area around Amiens as my target. I tried to go as far as possible behind enemy lines; for, only in that way does one gain a clear view of the opposition ... Only a few of our aeroplanes have succeeded in crossing over all the way to Amiens. I am proud that on every flight I made at least some turns over Amiens. Moreover, I never flew without bombs. The target was always Amiens ...’27

In response to these attacks, grouped French bomber units flew over German-held territory and targeted airfields. In turn, on Wednesday, 26 May, German 2nd Army headquarters ordered its sector’s Feldflieger-Abteilungen to bomb French airfields and aviation depots.28

Aside from the light combat activity, Berthold was content with his success and certainly with the quality of the men with whom he served. In June, he reflected:

‘I succeeded in having Buddecke transferred to my abteilung. Now we have all splendid fellows, such as: Oblt Fritz Böhmer; Leutnant der Reserve Anton Hirsemann; Ltn.d.Res Erwin Tütschulte; Rittmeister [Cavalry Captain] Friedrich Schueler van Krieken29 and Ltn Josef Grüner – all forceful officers of the good, old style, firm as iron in performing their duties and in service overall.

‘In terms of distances flown and numbers of combat missions, each crew seeks to surpass the others. True flying spirit. All for one and one for all! Moreover, we have the splendid ... Hptm Karl Seber [commanding officer] and Hptm Eberhard Bohnstedt30 [executive officer] at the head of the abteilung. Both constantly strive to keep us all out of trouble, the emphasis and attitude is always refreshing and the same spirit is raised among the non-flying mechanics and non-rated men. They do not have it easy, but they do the job.

‘Ltn Hans-Joachim von Seydlitz-Gerstenberg31 – or, as I call him “Seidenspitz”32 – is, to be sure, the most superb of them all. Although severely wounded in an air fight and not yet completely healed, he fled from the military hospital and tried desperately to be able to continue to fly; to do that, he had to be lifted into the aeroplane.’33

Berthold knew that it took more than iron will to prevail during defensive or offensive aerial combat. When FFA 23 received the weapons it needed, he wrote in his diary:

‘At last ... our reconnaissance aeroplanes are being equipped with machine guns. The French already had them even in peacetime ... Machine guns for our aeroplanes came only sporadically. Now, a year after the war began, many aeroplanes still have only pistols. We cry out for machines that attack – we do not want aircraft that retreat.’34

The delay in equipping German aircraft with machine guns is inexplicable. In 1920, the pre-war aviation organiser and chronicler Major Georg Paul Neumann35 wrote:

‘Even before the war, thought had been given to using the capability of the air-cooled machine gun as the best suited ... weapon for aerial combats, which, admittedly, were hardly anticipated. But testing was not completed, despite several recommendations, including having the fixed machine gun controlled by the engine [i.e., able to fire through the propeller arc], patents for which existed before the war...

‘Above all, the aeroplane was seen as a strategic means of long-range reconnaissance flights, and aerial combats were not considered ... Thus, it was [not until] the spring of 1915 that the air-cooled Parabellum machine gun was installed, initially for the observer, for defensive purposes ...’36

Berthold’s observer had an opportunity to use his new swivel-mounted machine gun on Tuesday, 8 June, when French forces attacked the German 52nd Infantry Division on the Somme sector. In response, Feldflieger-Abteilungen 23, 27 and 32, supported by the Bavarian FFA 1b,37 were out in force, photographing French positions and engaging enemy aircraft. But Berthold garnered no individual glory that day, which may have frustrated him. He was a rather highly-strung individual and had a pressing need to be in action continually. A short time later, the otherwise robust Berthold collapsed, perhaps due to anxiety, about which he wrote:

‘As to my nervous system, I have not changed much; I am still the same old fellow, I feel as fresh as before. My collapse in June was probably of a serious nature, but soon resolved. Only my stomach nerves are not holding up. At first, the doctor thought it was dysentery, but after two weeks I was back to my old self.’38

Fighters and Bombers Arrive

Further, Berthold may have been comforted by news about a new German machine gun development. Forward-firing and synchronised to fire through the propeller arc, the gun was installed on the new Fokker Eindecker [monoplane] fighter in May 191539 and such guns could be fitted to two-seaters used by units such as FFA 23.

Meanwhile, the abteilung had begun using AEG G.II two-engine bomber aircraft and Rudolf Berthold had been sent to the factory at Hennigsdorf, near Berlin, to take delivery of one. It was among Germany’s largest aircraft: with a wingspan of 52 feet and 6 inches, length of 29 feet and 10 inches and a loaded weight of 5,434 lbs.40

AEG G.II 21/15 seen shortly after Berthold delivered it to FFA 23. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

In August 1915, Berthold wrote in his diary:

‘For months we have flown the Grosskampfflugzeug, which we call the “Big Barge”. It has two engines that together produce 300 horsepower. It has places for two to three observers, two machine guns and can carry a bomb-load of 200 kilograms. I have flown it in combat and it is well suited ...’41

At about the same time, Berthold contended that he ‘passed’ on the opportunity to fly one of the nimble little single-seat Fokker fighters. He stated: ‘In July, I was supposed to receive a Fokker Eindecker. I gave it up in favour of Buddecke, who asked me to do so. He was familiar with the type from his time in America ...’42

But there is more to the story. In the summer of 1915, the synchronised machine-gun-armed Fokker was unique to aerial warfare and, while German commanders were pleased by its success, they also feared its capture. A German 3rd Army air commander spoke for his peers in other army groups when he reported: ‘These aeroplanes go up only to repel [enemy] aircraft that have broken through [our defences]; they have orders to not cross the lines under any circumstances.’43

Most likely, that restriction caused the ever-aggressive Berthold to have second thoughts about flying FFA 23’s first Fokker Eindecker. As he wrote in his diary:44

‘I do not want a Fokker yet, as one may not fly over the frontlines ... and I do not want to be a rear-area flyer. The little bird is indeed good in attacking, but it is flown too little at the Front; it would be ideal if I had both [my AEG and the Fokker] and could fly each as needed. It is unfortunate that one cannot attack with the G-type, but it is too unwielding for that purpose. Controlling the long wings, which are like arcs, takes a great effort in terms of flying.’

Hinting at the real reason he received the new fighter aircraft, Hans Joachim Buddecke wrote: ‘... finally I got my Fokker, which scarcely anyone else wanted’.45

Buddecke was not bothered by constraints, as he knew British and French aircraft would venture over German-held territory. And Berthold was happy, for the moment, that he could attack Germany’s adversaries within their own lines.

Consequently, it was supposed to be a routine event when, on Wednesday, 15 September 1915, Rudolf Berthold took off in AEG G.II 21/15 on a bomb-dropping mission over French lines. The sudden appearance of heavy storm clouds, however, compelled him to cancel the flight and return urgently to his airfield at Roupy. But no sooner had the big bomber touched down when it nosed over. The long wings and double landing gear, one under each engine, made landing the AEG G.II difficult at times and this type of accident was not uncommon. In any case, neither Berthold nor any of his crew had been injured, but the aeroplane was badly damaged and had to be dismantled and sent back to Germany by rail.46

Dutch-born aircraft manufacturer Anthony H.G. Fokker and an early unarmed model of the monoplane that, when equipped with a synchronised machine gun, gave Germany an advantage in early aerial combats. (Volker Koos)

Berthold could only return to flying two-seat reconnaissance aeroplanes.