THE FIGHTER ACE ERA BEGINS

‘Berthold always had big plans, so he was never at a loss for words. His thoughts were already far ahead, on the first gust of wind, the first shot of anti-aircraft fire over the lines... he could already envision ... how to manoeuvre the approach.’1

HANS JOACHIM BUDDECKE

While Rudolf Berthold carried out reconnaissance flights from Roupy, reports began to circulate within the Fliegertruppe of two Fokker Eindecker pilots from Feldflieger-Abteilung 62 who were gaining success and recognition by individually shooting down hostile aeroplanes. By this time, FFA 62’s Leutnant Oswald Boelcke had scored two aerial victories while flying one of the diminutive and deadly Fokkers2 and his comrade Ltn Max Immelmann had two confirmed ‘kills’ and claimed two others3 with his Fokker. Then, on Sunday, 19 September 1915, Berthold’s best friend in FFA 23, Ltn.d.Res Hans Joachim Buddecke successfully brought down a British two-seater for his first air combat triumph4 – also while flying a Fokker Eindecker.

Berthold celebrated an achievement of another sort when, on 21 September, he was promoted to Oberleutnant.5 A few days after that, he was off to Germany to take delivery of FFA 23’s replacement bomber, AEG G.II 26/15.6 Given the short time he was away from the unit, Berthold must have flown – or been flown – about 800 kilometres to the AEG factory and then returned in the new aeroplane. At a normal cruising speed of about 100 kilometres per hour, the journey by air would have taken a day and a half, with re-fuelling stops; the journey by rail could have taken from several days, including stops and train changes.

Due to intermittent bad weather at the end of September 1915,7 Berthold first flew AEG G.II 26/15 in combat on Friday, 1 October. The mission was a flight of over 100 kilometres each way from Roupy, west of St. Quentin, to a major British barracks complex at Abbeville and back. Capable of a maximum speed of just over 145 kph8 and including time to circle over the target, the AEG could make the entire flight in just over two hours – longer if there were strong head winds. Berthold was accompanied by his favourite observer/gunners, Leutnants Josef Grüner and Walter Gnamm.

Returning from Abbeville during favourable weather the following day, Berthold and his crew were attacked by a Vickers F.B.5,9 and eluded it. The crew made almost daily bombing and reconnaissance flights over hostile territory – on 4 October, for example, they dropped 200 kilograms of high explosives on the Abbeville barracks.10 But Berthold surely regarded the abwehr [air defence] missions they flew on 15, 18 and 22 October as highly desirable.11 During those sorties, their AEG served as a well-armed gunship, ready to deal with hostile aircraft. In that capacity, they bolstered flights ordinarily assigned to FFA 23’s Fokker Eindeckers.

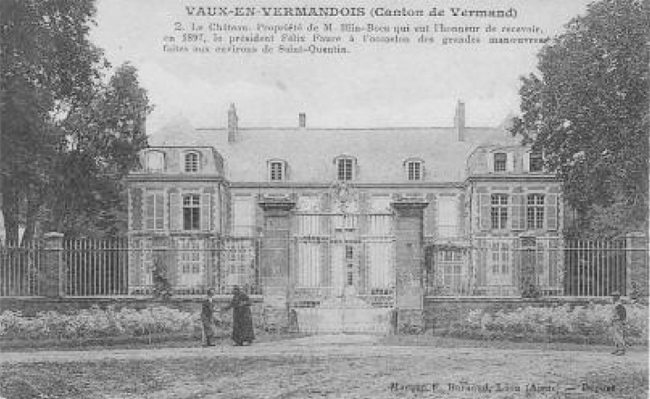

The château at Roupy was expropriated for housing and its spacious grounds became an airfield for FFA 23 in 1915.

Royal Visitors

Berthold and his crew reported no aerial combat during those flights, but they had a harrowing experience on Saturday, 23 October. That afternoon, FFA 23 prepared for an inspection visit by high ranking officers and dignitaries on a battlefield tour to boost troop morale. This group included Prince August Wilhelm of Prussia, the twenty-seven-year-old fourth son of the kaiser, and Duke Ernst August of Braunschweig. Berthold was scheduled for a flight to Abbeville, after which he would be on hand to welcome the visitors.

On the way out to his aeroplane, Berthold encountered Hans Joachim Buddecke, who recalled:

‘Berthold always had big plans, so he was never at a loss for words. His thoughts were already far ahead, on the first gust of wind, the first shot of anti-aircraft fire over the lines; even before the hours that would bring him over Amiens to the coast, he could already envision the encampment at the mouth of the Somme river and how to manoeuvre the approach. He was angry ... as he always was up to the moment of success. In the meantime, his nervous tension proclaimed itself in exquisite expletives, which he discharged too easily at his two observers – even during the most difficult moments in the air ...

‘[Before take-off] you look at every flyer – you will always find something ... even the bravest person has his own little superstition. Usually it manifests itself in the clothing, but often in other actions, such as before each flight when a comrade urges his observer to rub the propeller for luck.

‘Whether it was a superstition with Berthold or something else ... first he put on his regimental uniform jacket, which was actually worn out, even though he had it only since 1914 ... Over the jacket Berthold wore a fur coat, then a scarf, horn-rimmed glasses on his face and a large pair of flying goggles over them, then a thick wool balaclava helmet around the head and ... the crown in the form of an oily brown leather beach hat.[His orderly] Bart had washed this talisman – in hot water, of course – and it shrank and was no longer any sort of head covering. That did not matter. The hat had to be there when Berthold flew...’12

The bomber took off and other members of FFA 23 went about preparing for the inspection. The distinguished guests were scheduled to arrive at Roupy airfield at 2:00 p.m. But suddenly, at 1:45, Buddecke was dispatched to nearby St. Quentin to intercept a hostile aircraft heading their way. Soon thereafter he was joined by Ltn.d.Res Ernst Freiherr von Althaus in a second Fokker Eindecker. Just after the fighter pilots left, Berthold returned in the AEG – somewhat the worse for wear, according to Buddecke:

‘Many shreds of fabric hung out from the rear observer’s seat. Following the attack on Abbeville, a piece of shrapnel from a big shell had passed between the observer’s legs without hitting anything. It was a glorious event that the brave lads had survived ...’13

Oblt Rudolf Berthold’s AEG G.II 26/15 was the focal point of visitors viewing an aerial combat overhead, as during the event on 23 October 1915. (Tobias Weber)

Buddecke pursued his quarry, a British B.E.2c two-seat bomber, down to 100 metres’ altitude, within sight of Roupy. The newly-arrived guests joined others at the airfield, watching as the hapless two-seater continued downward. Then, its tail reared up and the biplane plunged to the ground, just short of the airfield.14

German soldiers soon arrived at the crash site and removed the bodies of the twenty-seven-year-old pilot, Captain Cecil Hoffnung Marks, and his observer, Second-Lieutenant William George Lawrence, age twenty-five. The observer was a younger brother of Captain (later Lieutenant-Colonel) T.E. Lawrence, best known as Lawrence of Arabia. Subsequently, both British airmen were buried at St. Souplet, northeast of St. Quentin.15

The afternoon’s display of flying skill and bravery must have impressed Duke Ernst August of Braunschweig, as he took a moment to express his appreciation. A few words to his aide-de-camp produced the necessary tokens of gratitude. At the end of the day’s events, Buddecke wrote:

‘As the highnesses climbed into their cars and gave all of us good, sincere handshakes, the duke presented three of his crosses with their beautiful blue and yellow ribbons. It was truly splendid.’16

Ernst August bestowed a trio of his Duchy’s third-highest military decoration, the Kriegsverdienstkreuz [War Merit Cross], an honour that he had authorised a year to the day earlier.17 They went to Buddecke and Althaus for ‘protecting a high personage from an enemy bombing attack’.18 As a noted German World War I aviation awards expert, the late Neal W. O’Connor, wrote: ‘protocol would [have] required the duke to recognize [FFA] 23’s leader [Hptm Karl Seber, by also] handing out the cross [to him] on this occasion.’19 Having already received high honours, Rudolf Berthold could appreciate what a fine moment it was, but he probably wondered when his time of glory would come again.

A Deadly Encounter

Berthold and his comrades returned to routine bombing raids until Wednesday, 3 November, when they again shared abwehr duties with FFA 23’s two Fokker Eindeckers.20 The AEG crew returned to Roupy with no success for their efforts, but, three days later, their luck changed when they spotted a Vickers F.B.5 over enemy-held territory and went after it. A Royal Flying Corps communiqué reported: ‘When north of Péronne, the [F.B.5 crew] were attacked by a Fokker [sic] biplane with passenger and machine gun. Unperceived till within 150 yards, the Fokker dived from 200 feet above them and opened fire at 100 yards.’21

The British crew misidentified their opponent but, through skilful flying and proficient aerial gunnery, they drove off their attacker. Again citing the RFC communiqué: ‘The ... [F.B.5 crew] are convinced that the observer of this [German] machine was put out of action and other serious damage was done.’22

In fact, the British gunner, 2/Lt Edward Robinson of 11 Squadron, RFC, had mortally wounded his German counterpart, Ltn Josef Grüner. Despite Berthold breaking away from the fight to rush his friend to medical facilities at the nearby air depot at Château de Grand Priel, Grüner could not be saved. He died the next day.

Berthold sunk into a deep melancholy over Grüner’s death. Perhaps recalling Berthold’s delicate emotional state in June, Hptm Seber granted the pilot a few weeks of home leave to recuperate. Seber knew that, when in top form, Berthold was a courageous and valuable member of FFA 23 and now his fragile emotional state needed to heal.

During his time away from the unit, Berthold apparently recovered from this episode of what in today’s parlance would be called post traumatic stress disorder. He returned to FFA 23 in a better frame of mind, but now – more than ever – he felt compelled to become a fighter pilot.

A Fokker E.II with a 100-hp engine23 arrived in October, but Berthold was still on leave and so the aircraft was assigned to Buddecke. Oblt.d.Res Ernst Freiherr von Althaus, a newer pilot, but senior to Berthold in date of rank,24 flew Buddecke’s relatively ‘old’ Fokker to a nearby aviation facility and received a newer Eindecker.

Berthold understood how he missed that opportunity to be assigned an Eindecker and continued to fly the AEG G.II without complaining. But the lingering memory of Grüner’s death inspired in him an even more resolute sense of his duties. He wrote in his diary: ‘Now I insist on flying a single-seat aeroplane. I want to be alone. And I will get a single-seater. It will be an older machine, but that is all the same to me. I want only to fly ... alone!’25

Until Berthold’s wish could be fulfilled, he and other AEG crews had significant roles in taking defensive actions against British and French aircraft over the Somme sector, which would become so important in 1916. Joint flights by FFA 23’s AEG and its two Fokkers26 gave the unit’s Eindecker pilots time to refine their skills. Royal Air Force historian H.A. Jones commented on Eindecker tactics during the autumn and winter of 1915:

‘The tactical use of fighters was still obscure, and the Fokkers were undoubtedly robbed of their full effectiveness by being allotted in small numbers to various flying units ... to take on what came their way. Their method of attack drew inspiration from the hawk. The Fokker pilot would cruise at great heights ... and await the passing of suitable victims. He would then swoop down from behind, coming when possible out of the sun so that his opponent might have no warning before he was startled by the rattle of a machine gun. One long burst of fire came from the Fokker as it dived past ... If the British [or French] aeroplane was not shot down and persisted in its work, the German pilot would climb again and repeat his swift diving attack ...’27

Hans Joachim Buddecke was a successful practitioner of the swift-diving tactic. He shot down three enemy aeroplanes from September through November.28 Early in December, however, Buddecke was transferred from FFA 23 to an air unit in Turkey to demonstrate his air-fighting skills for Germany’s allies in the Ottoman Empire.29 With that development, Berthold’s luck changed. By virtue of his experience, Freiherr von Althaus received a newer Fokker and Berthold was assigned an older machine. He still had to learn how to master the nimble little monoplane, but at last he was a flying alone in a true fighter aeroplane.

Initially, Berthold remained scoreless and his promise to Grüner was unfulfilled. When Althaus shot down British two-seaters on 5 and 28 December,30 however, Berthold flew with him,31 continuing to gain valuable operational experience in a Fokker Eindecker.

Birth of a Fighter Unit

In late 1915, various German army group headquarters began to deploy monoplane fighters as operational sub-units to protect reconnaissance and bombing aircraft. Thus, a system of Kampfeinsitzer Kommandos [single-seat fighter detachments] – abbreviated KEKs – was established on the Western Front.32 As part of that effort, on Tuesday, 11 January 1916, a KEK was formed at an auxiliary airfield at Vaux-en-Vermandois,33 a short distance from FFA 23’s main airfield at Roupy. As he had more overall flying experience than other pilots in the unit, Rudolf Berthold was designated as officer in charge of the temporarily-assembled KEK Vaux, as the detachment became known. He and Althaus represented FFA 23 and, after more Fokker Eindeckers arrived, they were joined by pilots from other Feldflieger-Abteilungen to form a dedicated fighter unit.

Berthold was pleased with his new circumstances, now that he had the means to aggressively attack enemy aircraft, and he wrote in his diary about his work at Vaux:

‘Located about a half hour away from our Feldflieger-Abteilung base, Château Vaux reposes in a big, old park, far away from the main traffic route. When I received my AEG aeroplane last August and I needed space for a big hangar, I decided to use the grounds in the vicinity of the château as an airfield, with the château itself to be our living quarters ... A big barn was converted immediately to house my bird. The fields in front of the barn were transformed into a landing field.

‘The whole place was ideal for our purpose, only thirty paces away from where we would stay. We formed a small Kommando [detachment] of six officers and thirty men. We were independent and yet at all times linked to the respective abteilungen.

KEK Vaux took its name from another expropriated château at Vaux-en-Vermandois where German flyers were housed. The adjacent flat landscape made an ideal airfield. (Heinz J. Nowarra)

‘Gradually the G-type aeroplanes disappeared from all of the combat aircraft units [whose members made up KEK Vaux] and thus the observers were also reassigned. It became lonely at our place for a short time, but I endured it. When more single-seat fighter aeroplanes came to the [2nd] Army, I assembled my Fokker Kommando. Thus, now we had five single-seaters and, as we flew daily, we held back the French flyers ...

‘Single-seaters can be at the Front continuously only, to some extent, during favourable weather, so in January the ... [opposition] was somewhat restrained. The month ... was difficult, and it almost demoralised me. I flew and flew, but did not have an opportunity to fire my guns. I built a dummy aeroplane on the ground and attacked and shot at it diligently. It helped me feel more secure about myself and my ability.’34

The new, overly cautious approach to single, and double, aircraft flights over the lines, which had been so successful for Allied airmen, can be attributed to the increasing ‘kill’ scores recorded by Fokker Eindecker pilots. Reacting to that situation, RFC headquarters ordered on 14 January:

‘Until the Royal Flying Corps are in possession of a machine as good as or better than the German Fokker [monoplane] ... a change in the tactics employed becomes necessary ... In the meantime, it must be laid down as a hard and fast rule that a machine proceeding on reconnaissance must be escorted by at least three other fighting machines ... From recent experience ... the Germans are now employing their aeroplanes in groups of three or four, and these numbers are frequently encountered by our aeroplanes. Flying in close formation must be practised by all pilots.’35

After the most successful Fokker Eindecker pilots, Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann, had each shot down eight aeroplanes, on 13 January 1916 they were presented with the Orden Pour le Mérite.36 Officially the highest bravery award of the Kingdom of Prussia, the decoration became, de facto, the German Empire’s highest military honour. Attaining it also became keenly desired by most German airmen.

Rudolf Berthold and his ground crew posed uneasily by his Fokker E.III 411/15 at KEK Vaux. (Greg VanWyngarden)

On Wednesday, 2 February, medals were not on Rudolf Berthold’s mind as much as the weather: intermittent rain and low clouds did not offer much hope for aerial combat. While other KEK Vaux pilots were out looking for targets, Rudolf Berthold and Ernst von Althaus were inside the château at Vaux, warmed with mugs of coffee. But a telephone call at about 3 p.m. sent them running for their aeroplanes. An enemy aircraft had been spotted over Péronne, a short distance away.

It began to rain again as they took off, but after attaining 2,000 metres’ altitude, they found a hole in the clouds. Within that space they saw a pair of French two-seat reconnaissance aeroplanes and headed for them. A short fight ensued and Berthold shot down his opponent, a Voisin LA biplane.37 Later, he was officially credited with his first aerial victory. His quarry came down intact in a field in Chaulnes, some thirty-five kilometres west of St. Quentin. The French pilot, twenty-nine-year-old Caporal [Corporal] Arthur Jacquin,38 was unharmed and taken prisoner; the observer, Sous-lieutenant [Second-Lieutenant] Pierre Ségaud,39 age thirty-seven, was killed during the fight. Later, Berthold said he felt he had avenged the death of his observer/gunner, Ltn Josef Grüner40 – ‘an eye for an eye’ ...

Freiherr von Althaus pursued a Nieuport two-seat biplane and set it on fire with his incendiary ammunition. It crashed and burned near Biaches, a few kilometres outside of Péronne.41 Both crewmen were killed. Althaus was credited with his third confirmed aerial victory.

Berthold’s Second Victory

The following Saturday, 5 February, Berthold wrote:

‘Today I brought down my second opponent, this time an Englishman. Over Bapaume, I took him out from a formation of five aeroplanes. It did not take long; he was all done after the first shot.’42

Berthold’s account overly simplifies his actions in forcing B.E.2c 4091 of 13 Squadron, RFC, to land between Grévillers and Irles. As was commonly done, an examination of the aircraft by a German ground unit determined that the two-seater sustained numerous ground-fired hits. Nevertheless, a 2nd Army Senior Command report concluded: ‘The aeroplane ... was shot down by a Fokker of Feldflieger-Abteilung 23, [piloted by] Leutnant Berthold.’43

The British pilot, 2/Lt Leonard John Pearson, was unwounded and taken prisoner. His observer, 2/Lt Edmund Heathfield Elliott Joe Alexander, suffered a ‘shot in the right forearm and hand’44 and was taken to a first-aid station before being turned over to the German Feldgendarmerie [field police] for transport to the rear area and processing as a prisoner of war.

Berthold Shot Down

Berthold thought he had his third victory in his gun-sight when he and another Fokker pilot dived on three B.E.2c aircraft – one serving as a reconnaissance machine and the other two as escorts – on the morning of Thursday, 10 February. One RFC source noted that the first ‘single-seater Fokker ... opened fire at seventy-five yards, gradually closing to twenty yards, and [his] tracer bullets were seen to hit the [British] machine. The German dived and at the same time a second Fokker attacked.’45 2/Lts C. Faber and R.A. Way in B.E.2c 4132 of 9 Squadron, RFC,46 were hit, but ‘Lt Faber recovered, righted the machine, climbed to 3,000 feet, and landed ... safely on the [squadron’s] aerodrome.’47

The other two British aircraft concentrated on Berthold in the second Fokker. Lt R. Egerton and his observer 2/Lt B.H. Cox opened fire ‘and clearly saw tracer bullets enter the cowl of the Fokker, which dived steeply and landed safely in a field south of Roisel.’48 2/Lts V.A.H. Robeson and T.E.G Scaife ‘in the reconnaissance machine also fired at this Fokker and saw him dive to the ground’.49

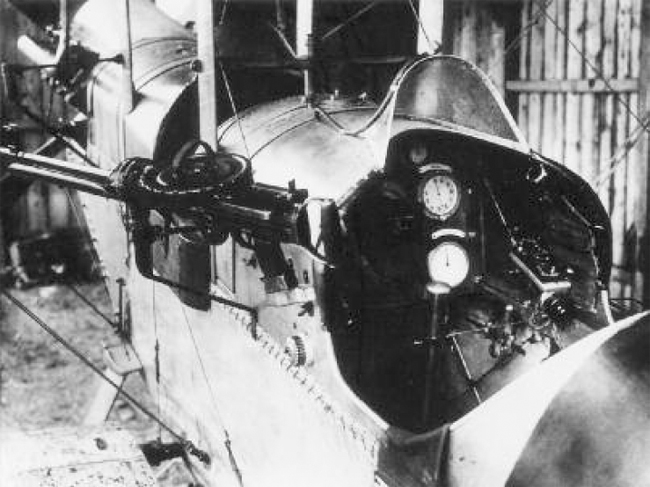

The observer’s flexible machine gun on a Royal Aircraft Factory B.E.2c, the type that sent Berthold down on 10 February 1916. (Volker Koos)

Berthold was lucky to survive that fight. As it was, he received ‘numerous hits, including two in the fuel tank ... [and] was forced to land near Bernes, west of Hervilly; he slightly injured his left hand’.50 There is no doubt that Berthold tangled with the trio of 9 Squadron B.E.2c aircraft, as he landed near Bernes, a few kilometres from Roisel, where the British airmen last saw him.

In any event, Berthold’s injury was of little importance – or, at least, he did not let it affect his flying – as he flew one of FFA 23’s two-seat biplanes during a night-time bombing raid. On the evening of 20/21 February, Berthold dropped some 230 kilograms of high explosives and incendiaries on railway stations and other military objectives in Amiens and, farther east, in Lamotte-en-Santerre.51

Also on the morning of Monday, 21 February, a massive German artillery bombardment of fortifications at Verdun52 in north-eastern France opened one of that war’s most horrific battles. Rudolf Berthold was far removed from that fighting, but would become involved in another carnage-laden onslaught: the Battle of the Somme.

Berthold’s courage and perseverance were recognised on leap year day, 29 February 1916, when he was honoured by his Bavarian homeland. He was presented with the Militär-Verdienst-Orden 4. Klasse mit Schwertern[Military Merit Order 4th Class with Swords]. Berthold became one of only twelve aviation recipients of the 4th Class award throughout the war. And, as medals became the acknowledged currency of bravery and honour recognition, Berthold could take pride in knowing that he joined such illustrious company as Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann.53 Berthold was the sole FFA 23 recipient of this decoration.

FFA 23’s fighter detachment began to enjoy the success of the Fokker supremacy, as Berthold and two other KEK Vaux aircraft proved on Monday, 13 March, when they dived on a reconnaissance flight from 8 Squadron, RFC. According to a British report:

‘The 3rd Army reconnaissance [flight] was attacked by three Fokkers … At Moeuvres two … Fokkers attacked from behind, opening fire at about 200 yards. Almost immediately one of the escort machines (2/Lt Orde54 and 1/AM Shaw [in] B.E.2c 4151) turned and began to spiral down. The Fokkers were engaged by all of the remaining machines of the reconnaissance [flight] and eventually driven off.’55

Orde’s aeroplane came down at Bourlon. It was confirmed as Berthold’s third victory.56

Berthold’s Fourth Victory

Berthold’s next air combat claim, on Saturday, 1 April 1916, is not as easy to prove. And confirming aerial victories was (and still is) important for fighter pilots; for, in addition to fulfilling patriotic duty, combat pilots understood that higher ‘kill’ scores generally resulted in greater rewards. In tracking these combats as completely as possible, historians seek to assemble reports and other accounts to reasonably propose which airmen were involved in which air fight – essentially, who shot down whom. With that research interest in mind, throughout this book the author will propose names and information about Allied airmen who Rudolf Berthold very likely opposed in air combats.

In the case of the 1 April 1916 air battle, Berthold contended that he shot down a Farman two-seat biplane near Lihons, just over thirty-five kilometres west of St. Quentin. The aircraft is said to have ‘plunged to the ground burning, part on our side of the lines, part over enemy lines’.57

Based on existing historical evidence, the best match among French losses that day was a Farman F.40 reconnaissance aircraft from Escadrille MF 54, crewed by Sgt Louis Paoli58 and his observer, Lt Alfred Braut. As MF 54’s airfield at Savy-Berlette59 was less than sixty kilometres north of Lihons, it is reasonable to assume that Paoli could have flown that distance and fought with Berthold. However, a contemporary French magazine reported that, while ranging artillery fire, Paoli’s aeroplane ‘took a direct hit, killing the observer, [and leaving] Paoli ... badly wounded. Nevertheless he was able to bring his aeroplane back to our lines, but died a few hours after landing.’60

As a practical matter, if Paoli’s wood-frame, linen fabric-covered aeroplane had taken ‘a direct hit’ by an artillery shell, it would have been turned into confetti. On the other hand, ‘a direct hit’ by Berthold’s machine gun could have left the Farman F.40 damaged, but reasonably able to return to its airfield. In any case, available evidence convinced Berthold’s superiors that he had attained a fourth aerial victory.

The fuselage of a Farman F.40, a type that Berthold claimed on 1 April 1916, shows the gunner’s access hatch and his single Colt-Browning 0.30-calibre machine gun. (Kilduff Collection)

Exactly two weeks later, on 15 April, Rudolf Berthold received his highest military honour thus far when the Kingdom of Saxony presented him with its Ritterkreuz des Militär-St.-Heinrichs-Orden [Knight’s Cross of the Military St. Henry Order].61 The award citation noted: ‘During the campaign, Ltn Berthold was one of the most successful fighter pilots. In the period 5 February to 13 March 1916, he was one of the first to fly the new Fokker machine and won several air battles as a member of Royal Saxon Feldflieger-Abteilung 23.’62 In addition to the handsome medal, Berthold received a conferral document signed by King Friedrich August III.63

Berthold’s Fifth Victory

As if to further validate the award, the next day, 16 April, Berthold shot down a British two-seater that was directing artillery batteries against German forces east of Albert. He was so determined to halt this source of deadly messages to his enemies that he braved his own anti-aircraft fire while attacking his target. In the informal tradition that arose spontaneously among aviators on both sides of the lines, after attaining a fifth victory Berthold became acknowledged as a ‘fighter ace’, an honour that earned him high respect among his peers and people at home looking for heroes. This latest victory was soon confirmed, as Berthold’s shots hit the pilot, whose aeroplane – B.E.2c 2097 of 9 Squadron, RFC – came down within German lines south of Maurepas. According to a British report:

‘2/Lt W.S. Earle64 (pilot) and 2/Lt C.W.P. Selby65 (observer) were bought down in the German lines east of Maricourt as the result of a fight in the air. The machine was apparently on fire. Lt Earle was killed and his observer severely wounded.’66

Rudolf Berthold became an ace when he received confirmation for his fifth aerial victory, B.E.2c 2097, seen here after it crashed. (Rainer Absmeier)

No doubt due to the severity of his wounds, Selby was later repatriated to Britain, where he recounted his fateful encounter on 16 April 1916:

‘Our machine was attacked by a Fokker at 10:05 a.m. while the [German] AA guns were still firing … My pilot was killed by the first ... [bullet] fired, but the machine remained in control long enough to allow me to fire a drum [of ammunition], luckily hitting the attacking pilot in the leg. This I learnt when I was in the same hospital as him at St. Quentin.

‘When the machine began to [lose] control, I climbed back to the pilot’s seat and endeavoured to regain control, but found the rudder wires shot away. The machine then fell, controlled only by the elevators. I luckily managed to get clear, falling about fifty feet from the machine, thus escaping any fatal injuries.’67

Selby was lucky to have survived such a fall at a time when aeroplane crews were not equipped with parachutes. While he may have fired a machine gun at Berthold, he did not hit the German ace and send him to the hospital. Rather, within a fortnight Berthold was brought down by something as prosaic as engine failure over his airfield. But he ended up in the main military hospital in St. Quentin, where the patient in the next room was 2/Lt Selby. It would be the first of several hospital stays for Berthold and, in this case, would keep him out of action for the next four months.