LEADERSHIP IN THE AIR

‘There were no pilots in the staffel who would have hesitated to shoot down an opponent in aerial combat. This was not my doing; I had merely trained and properly led them against the opposition...’1

RUDOLF BERTHOLD

Failures in the Battle of Verdun led to major changes within the German military structure. On 29 August 1916, General der Infanterie Erich von Falkenhayn, chief of the general staff and proponent of the Verdun offensive, was relieved of command and later retired. He was succeeded by Generalfeldmarschall [Field Marshal] Paul von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg, the renowned Eastern Front commander. The shift at the highest level benefitted the Fliegertruppe, as Oberstleutnant [Lieutenant Colonel] Hermann von der Lieth-Thomsen, the chief of field aviation, was a protégé of Hindenburg’s chief of staff, General der Infanterie Erich Ludendorff.

With Ludendorff’s support, von der Lieth-Thomsen (generally called Thomsen) was able to alter and improve the deployment of German aircraft and units. His efforts came to formal fruition on 8 October, when Kaiser Wilhelm II proclaimed that: ‘the growing importance of the air war requires uniting the entire air combat and air defence capabilities of the army, in the field and on the home front, into one entity.’2

The Luftstreitkräfte Emerges

With that action, the Fliegertruppe was transformed from a loose organisational structure into a unified command. Generalleutnant Ernst von Hoeppner, a thirty-seven-year-old military veteran and non-flyer,3 was appointed Kommandierende General der Luftstreitkräfte [commanding general of the air force] or Kogenluft in abbreviated form. To assure that the Luftstreitkräfte was included in major war developments, Hoeppner reported directly to Hindenburg at the Oberste Heeresleitung [Supreme High Command].

Oberleutnant Rudolf Berthold enthusiastically embraced the new Luftstreitkräfte’s evolution, but he saw a greater need for massed German efforts to stop enemy aircraft. He recorded in his diary:

‘My ambition was to concentrate the air units into larger entities, which ... would be guided by one hand. I proposed the use of Geschwaders [large formations or air wings] ... as a collective opposition.’4

As part of the reorganisation that led to development of the Luftstreitkräfte, individual Armee Stabsoffiziere der Flieger [army aviation staff officers] were elevated to Armee Kommandeure der Flieger [army commanders of aviation] – abbreviated Kofl – and given greater responsibilities.5 Hence, in January 1917, Berthold met with Hauptmann Bruno Volkmann, the Kofl for Armee-Abteilung A, and in great detail proposed broader use of massed air units. His discussions with Volkmann were in vain, but, as Berthold noted in his diary:

‘... In spite of all failures, I continued to fight for my idea and, later, found support and understanding for my efforts from Hptm Wilhelm Haehnelt [5th Army Kofl], a far-sighted and forward-striving old flyer. But even he could not get through to a higher authority. Nevertheless, completely independent of other armies, he introduced this kind of organisation within his unit.’6

When Generalleutnant Ernst von Hoeppner was appointed to command the Luftstreitkräfte his highest award was Prussia’s Order of the Red Eagle 2nd Class with Swords, worn at the neck. Later he received the Pour le Mérite. (Kilduff Collection)

Jasta 14 Early Victories

On Saturday, 3 February 1917, Berthold received satisfaction from his work with Jasta 14 when the unit recorded its second aerial victory. Leutnant der Reserve Adolf Kuen shot down a two-engine Caudron G.4 bomber near Emberménil, less than twenty kilometres from its own airfield at Lunéville.7 The two French crewmen were killed and credit for the victory was awarded to Kuen.8 Berthold was gratified that the bomber had been stopped before it got too far into German-held territory.

Jasta 14’s third victory occurred on Sunday 11 February, when Oblt Berthold and Offizierstellvertreter [Warrant Officer] Hüttner patrolled over Parroy forest. Again, they were not far from the French airfield at Lunéville when they attacked five Nieuport XVII single-seat fighters. Despite the odds, the staffel record shows: ‘Hüttner forced one of the Nieuports to land ... The [enemy] aeroplane came down within German territory and was later repaired by the staffel. Berthold held off the other four and chased them away.’9 Hüttner was credited with his first victory,10 and the pilot of downed Nieuport XVIIbis No. 2405, Brigadier [Corporal] Lambert of Escadrille N 506, was taken prisoner.11

Four days later, Berthold received a distinctive honour from the chief of field aviation: a one-litre silver goblet known as the Ehrenbecher [cup of honour].12 Bearing the inscription ‘Dem Sieger im Luftkampf’ [To the Victor in Aerial Combat], the goblets were presented to combat flyers who shot down enemy aeroplanes; the first recipients were Oswald Boelcke and Max Immelmann, who had six and seven victories, respectively, when they were honoured on Christmas Eve 1915.13 The 20-cm tall goblets were produced by Godet, an exclusive jeweller in Berlin.14 Berthold received his Ehrenbecher after his eighth victory, but, in coming months, he and other air unit leaders would present the goblets to officers and enlisted men alike after they had scored their first air combat successes.

Oblt Rudolf Berthold was a constant presence at Jasta 14’s airfield at Bühl, assuring that his men understood the high standards he had set for the unit. (Greg VanWyngarden)

Berthold is seen climbing out of Nieuport XVIIbis No. 2405, which was captured after a fight in which he participated. (Lance J. Bronnenkant)

An example of the Ehrenbecher that Berthold received from the Chief of Field Aviation. (Kilduff Collection)

Jasta 14’s Albatros D.I and D.II aircraft were soon replaced by the improved D.III model. The type’s sleek appearance – with its pointed nose and streamlined, plywood-covered semi-monocoque fuselage – led to its being nick-named the haifisch [shark]. Fitted with a new high-compression engine15 and twin machine guns, the sleek fighter had speed and killing power, just like its voracious namesake.

Plans to transfer Jasta 14 in February raised hopes that the unit would leave the relative quiet of Alsace for greater challenges to the west. However, as Berthold wrote in his diary:

‘...the move meant we were only half satisfied [as] we did not go to face the British in Flanders; [rather] we went to Laon in the Aisne sector. I found ... such sad conditions there that I would not have considered them possible. We did not find suitable living quarters in any of the communities ...

‘Luckily, I had flown ahead by myself and left orders that the staffel should be prepared to relocate only after it received my orders by telegram. For two weeks I worked alone with the people responsible for providing quarters. I constantly received orders that my staffel had to move, but I always sent one answer: First, there must be quarters for my staffel and not before. Finally, the move went forward ...’16

Berthold did not know of high-level German plans to capitalize on the inhospitable environment he complained about. As the Royal Air Force historian H.A. Jones pointed out: ‘On the 3rd of March the Germans captured an important staff memorandum of [Général Robert Georges] Nivelle which fully revealed the French commander-in-chief’s strategy’17 for the coming French offensive in the Aisne sector. Thus, as another historian noted: ‘... the Germans had ample time to convert ... natural barriers into a veritable fortress.’18 German planners carried out a strategic withdrawal to what they called the Siegfried Line, named after the legendary Germanic hero who had been popularised in Wagnerian operas.

Berthold test-fired the guns in the newly-arrived Albatros D.III 2182/16. This aircraft is believed to be the first fighter on which his personal emblem was applied to the natural wood finish of the fuselage. Appropriately, he chose the winged sword of an avenging angel. (Greg VanWyngarden)

After Jasta 14 settled into its facilities at Marchais, Berthold’s Albatros D.III 2182/16 (centre) received final attention before he flew it in combat. (Greg VanWyngarden)

In mid-March Berthold felt that Jasta 14’s new facilities were ready for the unit and he ordered a caravan of lorries to journey over 200 kilometres southwest from Alsace to the Aisne. The new airfield was at Marchais, a town outside Laon and about forty kilometres from Berthold’s old airfield at Roupy. He recorded in his diary:

‘Within twenty-four hours of its arrival at the new airfield my Jasta was completely ready for combat ... There was a magnificent spirit in the staffel! Fourteen aeroplanes had been off-loaded from transport vehicles, assembled, test-flown and had their gun sights checked. Workshop, carpentry shop, office and quarters set up with the help of only 125 men – it was a masterly achievement...’19

On the staffel’s first full day at Marchais, Saturday, 17 March, it recorded its third victory. An Albatros ‘haifisch’ flown by Vizefeldwebel Otto Gerbig shot down a two-engine Caudron outside of Paissy. Demonstrating the close proximity of the aerial adversaries’ operating areas, the French bomber went down in a field less than twenty kilometres south of Jasta 14’s new airfield. The bomber was Gerbig’s first ‘kill’.20

A factory-fresh and unmarked Farman F-1, 40b-Type 61 two-seater, a type that Berthold claimed on 24 March 1917. (Christophe Cony)

A week later – on 24 March, Rudolf Berthold’s twenty-sixth birthday – he scored the unit’s fourth victory. With Ltn.d.Res Georg Michaelis flying cover, to assure his leader was not surprised from behind, Berthold attacked a Farman Type 61 two-seater between Aizy and Vailly-sur-Aisne. The French aeroplane was no match for the fast and manoeuvrable Albatros, which sent it down onto Folemprix Farm, southeast of Ostel. The Farman was ‘completely smashed to pieces ... [and] both crewmen21 were dead’.22 Kogenluft records listed this downed aircraft as Berthold’s ninth victory.23

Berthold’s Tenth Victory

Even before Général Nivelle’s offensive began, the east-west road from Laon to Soissons attracted the interest of French reconnaissance aircraft. On Thursday, 6 April, Berthold spotted a big two-engine Caudron R.4 near the road and shot it down over La Malval Farm in the town of Braye-en-Laonnois. The staffel reported that ‘two [of the French] crewmen were killed and one [most likely, the pilot] was wounded’.24 The downed aeroplane was confirmed as Berthold’s tenth aerial victory.25 It also had intelligence value, as noted in a Kogenluft report:

‘Oblt Berthold of Jasta 14 shot down a two-engine ... Caudron on 6 April 1917. The pilot’s seat has 8-mm thick galvanised iron armour in the shape of an armchair, [behind it] a carapace-like protective shield three-quarters of a metre high, a shield beneath the [pilot’s] derrière, and a shield on each side of the [pilot’s] thighs. According to the account of a French prisoner, this type of aeroplane is called ... Caudron “Cuirasse” [body armour]. The observer and the aerial gunner, however, are not protected by armour. The engines are also not armour-plated. The aircraft are said to be used for long-range flights.

Rudolf Berthold commanded Jasta 14 at the time the second Sanke card (No. 423) was issued. This time, he was depicted wearing his actual Pour le Mérite. (Kilduff Collection)

‘After an aerial combat with a ... Caudron, a Jasta 14 pilot [Berthold] saw that the aerial machine gunner sitting in the rear was slumped lifeless over the gun-mount, while the aeroplane flew on undisturbed. According to Jasta 14, only attacks from the front or hits to the engines have a chance of disabling [the aircraft]. The subsequent firing tests against the armour of the captured Caudron, however, revealed that tracer bullets penetrate the armour at 150 metres, and SMK [steel-cored pointed bullet] ammunition at 155 to 300 metres.’26

On 11 April, the hard-driving Berthold fought with an equally determined French pilot southeast of Laon, where he and Off.Stv Hüttner encountered a pair of single-seat SPAD S.VII fighters. After an extended fight, Berthold slipped behind his opponent and sent him down south of Corbeny.27 But then Berthold had to land at nearby St. Paul Ferme due to engine problems,28 possibly damage inflicted by his recent adversary. In any event, he was credited with his eleventh aerial victory.29

Beginning at about 11:30 a.m. on Saturday, 14 April, Berthold and three comrades patrolled near the main road southeast of Laon and initiated several air combats. First to attack was a twenty-two-year-old Berthold protégé, Ltn.d.Res Josef Veltjens, who went on to become a leading German World War I fighter ace. Over Craonne, Veltjens shot down a SPAD S.VII, the first of his eventual thirty-five confirmed aerial victories.30

A short distance away, Berthold pursued a Sopwith 1A2 (French-built version of a British two-seat) reconnaissance and bomber aircraft; he sent it down over Beau Marais Wood. The downed aircraft, attached to Escadrille N 15,31 was confirmed as Berthold’s twelfth victory.32

The two-seat Sopwith 1½ Strutter was built under license in France and designated the 1A2. Berthold claimed a 1A2 as his 12th victory. (Volker Koos)

On the ground, German combat engineers facilitated the withdrawal prior to the Nivelle offensive. According to H.A. Jones: ‘With a ruthlessness that exceeded their military needs, the [German armies] laid waste the countryside as they went. They fell back on defensive systems from which they could, at their wish, develop a counter-stroke at any moment.’33

While wrecking their former facilities, German forces destroyed the living quarters that Berthold and his comrades used a year earlier. The elegant châteaus at Roupy34 and Vaux were levelled. This destruction created an emotional conflict for Berthold. After flying over the area, he confided to his diary:

‘Below us we saw the abandoned territory. It looked terrible; a vast wasteland. Also our dear old Vaux had to be seen to be believed. The beautiful piece of land that we had tended so well became a heap of rubble. We [flyers] did not smash it to pieces, destroying other people’s property; we sought to protect it, even though the necessity of war disconnected our emotions to it ...’35

Berthold Wounded Again

The German air casualty report of Tuesday, 24 April 1917 reported that ‘one officer [was] killed, three severely wounded and two injured in emergency landings’.36 Among airmen wounded that day was Oblt Rudolf Berthold, who ‘had a fierce dogfight with a Caudron R.9. During the attack, Berthold was shot ... in the right lower shin and had to break off firing at the enemy, who then went back over the lines in a dive.’37

The incident occurred a day short of the anniversary of Berthold’s bad crash in a Pfalz Eindecker. Yet, with typical bravado, he wrote about the latest incident in his diary: ‘... luckily, it was a clean shot that passed right through [my shinbone]. Actually, it is quite remarkable, as my first wound was to my left leg and now [one to] the right leg; I have not yet been hit in the right arm – but I do not even want to think about that.’38 The wound was serious and, after Berthold left the field hospital, he was sent home on recuperative leave from 23 May to 15 June.39

Initially, Oblt Rudolf Berthold remained with Jasta 14 after he was wounded on 14 April. This photo, taken a month later, following the staffel’s move to La Neuville, also shows Vfw Gerbig (second from right), Vfw Bredow (behind Berthold) and Ltn.d.Res Veltjens (behind Bredow). (Lance J. Bronnenkant)

By the time Berthold left France, the overall conflict – known as the Second Battle of the Aisne – had come to a horrific end with high casualties on both sides. French losses were ‘augmented by the destruction of ... morale in widespread mutinies ...’40

Despite the ground war pause during Berthold’s absence, Jasta 14 found targets in the air and accounted for eight enemy aircraft.41 Upon his return, Berthold was initially pleased with those results and wrote: ‘My staffel works very well, it lacks only enemy flight operations to attack. It is quite something else with the British up in Flanders ...’42

Then, inexplicably, Berthold’s mercurial mood flipped from buoyant to sour and he saw his men in a negative light: ‘Gradually the joy of flying began to wane; I felt more and more that ... the attitude of the staffel was becoming lukewarm. The ambitious ones remained only because they did not want to abandon me.’43

To Berthold, the solution was obvious: he could not lead his men from the ground; he had to return to flight status and lead his men in the air. The first days of August 1917 offered no promise of victories for Jasta 14, so Berthold took the only action he could. Perhaps under the guise of going home on leave, he returned to Germany and found a sympathetic physician at the aviation replacement unit, Flieger-Ersatz-Abteilung 6, in Grossenhain, the same facility from whence he had gone to war three years earlier. There, he was pronounced fit to fly, even though the notice did not come through until 18 August 1917.44

Transferred to Jagdstaffel 18

The journey back to Saxony had been unnecessary, as the Luftstreitkräfte bureaucracy finally responded to his earlier requests to become more actively involved in the air war. During Berthold’s time away from Jasta 14, orders arrived, transferring him to command Jasta 18, which was assigned to Army Group Wytschaete with the 4th Army in Flanders.45 He took up his new post on Sunday, 12 August, and later wrote in his diary:

‘As so much was going on in Flanders, I requested to be transferred there. Up to the last moment I had hoped that the entire Staffel 14 would be allowed to go with me, but then came the order that I was to be the leader of Jasta 18 ... and so with a heavy heart I departed from my people and once again headed out alone toward an unknown destination.’46

Despite his emotionally-dramatic note, Berthold did not travel by himself. His arrival at Jasta 18’s airfield in Harlebeke, Belgium was recorded in another diary, that of twenty-three-year-old Ltn.d.Res Paul Strähle: ‘Oblt Berthold ... takes over the staffel and brings several pilots and mechanics with him.’47 The seasoned pilots accompanying Berthold were: Ltn.d.Res Josef Veltjens and Vfw Otto Gerbig, a civilian flyer before the war,48 and Vfw Hermann Margot, another former FFA 23 comrade. In return, a like number of Jasta 18 pilots49 and mechanics were sent to Jasta 14.50

Oblt Rudolf Berthold succeeded Rittmeister [Cavalry Captain] Karl Heino Grieffenhagen in command of Jasta 18. Grieffenhagen, commissioned into Dragoner-Regiment von Wedel (Pommersches) Nr. 1151 before the war began, later served with two-seat and single-seat fighter units and led Jasta 18 since it was formed on 30 October 1916.52 After being injured in a forced landing with Jasta 18, Grieffenhagen left frontline service to lead the Kampfeinsitzerschule [Single-Seat Fighter School] in Paderborn, Germany.53

Following their failed Aisne offensive, Allied planners shifted their efforts to the British Front in Flanders.54 Thus, Berthold arrived at Jasta 18 at a critical time, during the Third Battle of Ypres, in which British forces advanced steadily eastward. Although the staffel was an already-experienced and battle-trained unit, Berthold wanted to lead it his way.

He wrote in his diary: ‘In Flanders the British dominated the air; good fighter pilots were needed there. First I had to make my new staffel thoroughly prepared to fly. During the [rest] of August, we flew only practice flights ...’55 The last sentence is a misstatement, however, as Paul Strähle’s diary records daily air combats in good and bad weather during the early days of Berthold’s command of Jasta 18.

One element of flight that might be considered as training occurred on Thursday, 16 August, when Berthold insisted that all of the aircraft in the early afternoon flight take off in formation. Strähle commented that the simultaneous take-off was ‘a wonderful sight, but a little dangerous’.56 Following a minor lull, ground ‘fighting at Ypres re-intensified’57 and, overhead, Jasta 18 logged its first victory under Berthold. Off.Stv Johannes Klein, who had arrived at the staffel a few days before Berthold, drove down a SPAD near Passchendaele, northeast of Ypres; he received credit for his first victory.58

After Rudolf Berthold’s first meeting with his immediate superior, Hptm Helmuth Wilberg, the 4th Army’s Kommandeur der Flieger, he wrote in his diary:

‘I have found a new ally for my idea in Kommandeur [Wilberg]. At my recommendation, four staffeln were combined into so-called Jagdgruppen [groups] and each of these units was placed under the leadership of an old reliable officer who was also a proven fighter pilot. We still lacked them in even higher command positions over these gruppen, but we have taken a big step closer to the goal. We still do not have such excellent aircraft as our opponents have, so we will have to fight to win air superiority and we will do that only when a unified spirit reigns.’59

Grouping fighter units was not a new development. Four Jagdstaffeln had been combined to form Jagdgeschwader 1 [Fighter Wing 1] on 23 June 1917,60 also in the 4th Army sector. That assembly of Jastas 4, 6, 10 and 11 – each led by a noted fighter pilot – was commanded by Germany’s highest-scoring fighter ace, Rittmeister Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen, and it capitalised on his prestige as the Red Baron. But, as noted by Luftstreitkräfte Commanding General Ernst von Hoeppner, lesser known groupings of newly-emerged Jagdstaffeln had already taken place in the 5th Army sector61 after Berthold brought his ideas to that army’s Kommandeur der Flieger, Hptm Wilhelm Haehnelt. So it was fitting that, when the 4th Army announced a ‘formation of Jagdgruppen by combining Jagdstaffeln’, Berthold was assigned to command one of them, Jagdgruppe 7, comprising Jastas 18, 24, 31 and 36.62

For all of the success that Berthold then enjoyed, another aerial victory seemed to elude him. During an early evening flight on 17 August, he led the charge against a formation of British artillery spotters and their fighter escorts, but all he had to show for it was ‘several bullet holes’ in his aeroplane.63

During the kaiser’s review of forces at Courtrai, Rittmeister Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen (centre) headed the aviation contingent. The first row behind him included three other Pour le Mérite airmen, from left: Oblt Paul Freiherr von Pechmann, Oblt Eduard Ritter von Dostler and Oblt Rudolf Berthold. (Lance J. Bronnenkant)

Berthold’s fortunes improved on 20 August, when he was invited to participate in Kaiser Wilhlem II’s troop review of 4th Army units at nearby Courtrai.64 He was in good company with Rittmeister Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen and other Pour le Mérite flyers. Returning to Harlebeke, Berthold found he had received a photo and personal note from Prince Eitel Friedrich of Prussia, the kaiser’s second son and a commander in the 1st Guards Infantry Division. During the war, the monarch’s six sons were in uniform and most sent such mementoes to high-performing military officers to reinforce their mutual interests in service to the nation. In this case, Berthold had met the prince a few weeks earlier at a Sunday lunch near the 7th Army frontlines and found him to be ‘a basic and unaffected man with a stern view of things’65 – the same values Berthold considered himself to possess.

Berthold’s Thirteenth Victory

The following morning was also a fine occasion for Berthold, as he added to his aerial victory score. At 7:25 a.m., he led five of his men on a patrol over the Ypres salient and up to Roulers and Thourhout. Paul Strähle’s diary notes that, just over half an hour later: ‘A SPAD two-seater passed above us. Berthold attacked him. I followed and also attacked; finally, Berthold shot him down near Diksmuide ...’66

Once again, the heat of battle led to some confusion about the type of aerial adversaries encountered. Strähle identified Berthold’s target, later credited as his thirteenth victory,67 as a big French two-seater – in an area of all-British operations. Most likely, Berthold shot down a big British two-seater, Airco D.H.4 A.7577 of 57 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, which was then conducting aerial reconnaissance between Menin and Roulers, southwest of Diksmuide. Later, a German aeroplane dropped a message within British lines stating that the downed aeroplane’s pilot, twenty-year-old Lieutenant Cecil Barry68 and Second-Lieutenant Frederick Ewan Baldwin Falkiner, MC,69 age twenty-two, were both dead.70

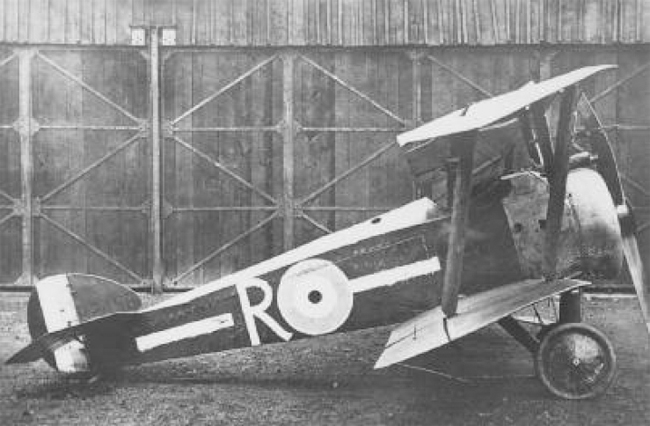

Berthold’s thirteenth victory was most likely an Airco D.H.4 two-seat reconnaissance aircraft, the type seen here. (Volker Koos)

Berthold’s First Double Victory

Despite making daily flights, it was almost two weeks before Berthold scored again. During an early morning patrol over Ypres on Tuesday, 4 September 1917, he attacked a lumbering R.E.8 two-seat artillery spotter. Considered to be ‘an easy mark for enemy fighters’,71 under the force of Berthold’s bullets it went crashing down on the northern edge of the city. A British source claimed the aeroplane was hit by German anti-aircraft fire, but no flak [anti-aircraft] units claimed a victory that day.72 Hence, it is reasonable to conclude that R.E.8 B.3411 from 7 Squadron, RFC, was counted as Berthold’s fourteenth victory.73 Both of its crewmen – nineteen-year-old 2/Lt Thomas Ernest Wray74 and his observer, 2/Lt Wilfred Stuart Lane Payne,75 age twenty-four – were killed in the fight.

At about 5 p.m. that day, Berthold was with two other Albatros D.IIIs when he dived on an R.E.8 over St. Jean, a few kilometres north of Ypres. According to a British report, the aeroplane was ‘attacked and shot down’ and the pilot, 2/Lt G.N. Moore of 9 Squadron, RFC, was wounded.76 However, Moore managed to return to British-held territory with his observer, who was uninjured.77 Apparently, Berthold’s fifteenth victory was confirmed on the basis of Germans who saw the badly stricken R.E.8 going down, although within its own lines.78

The following afternoon, Berthold and his comrades were patrolling near Roulers when they attacked British two-seaters approaching nearby Gitsberg. One of the two-seaters eluded the German fighters, but Berthold caught another, Airco D.H.4 A.7530 of 55 Squadron. After an eastward chase of less than twenty kilometres, he sent it down near Thielt. The crewmen – Lt John William Fraser Neill and 2/Lt Thomas Milligan Webster79 – were wounded and taken prisoner.80 The aircraft was credited as Berthold’s sixteenth victory.81

Jasta 18’s victory score continued to rise and on the afternoon of Saturday, 15 September, Berthold added to it by shooting down a British reconnaissance aircraft near Zillebeke lake, southeast of Ypres. There is no question that he prevailed over a two-seater in this area and it was confirmed as his seventeenth victory, but the Nachrichtenblatt [Kogenluft’s weekly intelligence summary] listed the British aeroplane as a ‘Sopwith’,82 while the 4th Army’s weekly operational report has it as an R.E.8. More likely, Berthold’s opponent that day was Airco D.H.4 A.2130 of 55 Squadron, RFC. The crewmen – Lieutenants Eric Edward Foster Loyd and Thomas G. Deason – were uninjured and taken prisoner.83

Of Rudolf Berthold’s 44 confirmed aerial victories, five were Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.8 two-seaters like the one seen here. (Volker Koos)

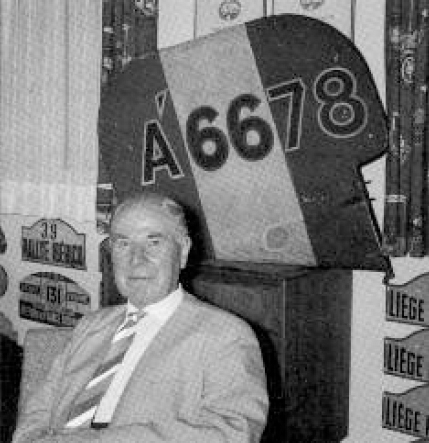

Ltn.d.Res Paul Strähle posed alongside 1 Squadron, RFC Nieuport 17 A.6678, which he brought down on 25 May 1917. (Greg VanWyngarden)

Berthold’s Second Double Victory

The next day, Berthold shot down a pair of R.E.8s. At about 6:00 p.m., he and his patrol – including Oberleutnants Harald Auffarth and Ernst Wilhelm Turck, and Ltn.d.Res Josef Veltjens – were near Ypres when, to the east, Berthold went after R.E.8 A.4693 of 6 Squadron, RFC. Following a short fight, he sent it down over Glengorse wood near Becelaere, killing both crewmen, 2/Lt Herbert Haslam84 and Lance Corporal Alfred John Linay.85 86 Some twenty minutes later, Berthold and his comrades split up and each singled out a two-seater in the area to attack. Berthold’s target was another R.E.8 – A. 4728 of 4 Squadron, RFC – which he shot down northwest of Becelaere. His shots hit the crewmen, Second-Lieutenants Leslie Glendower Humphries87 and Frederick Laurie Steben, killing the former and wounding the latter.88 In addition to Berthold’s nineteenth victory, each of his comrades was credited with an aerial victory that day.89

By this time, and no doubt following the example of Manfred von Richthofen and his gaudily-painted aircraft, Rudolf Berthold ordered his staffel’s aircraft to be painted dark blue on the fuselages and wings, and bright red on the engine areas. These unit markings were a tribute to his roots in the infantry, which for parade dress ‘wore red collars on their dark blue tunics’.90 As he wrote in his diary:

‘... in September ... the British knew the blue birds with red noses of Jasta 18 – my old Jasta in improved circumstances ... There were no pilots in the staffel who would have hesitated to shoot down an opponent in aerial combat. This was not my doing; I had merely trained and properly led them against the opposition. Their splendid performance showed what a ... spirit there was in the entire unit and in each individual pilot ...’91

Berthold’s Albatros D.III (left) in his new blue and red colour scheme with his flying sword insignia. The third aircraft from left, with the white arrow marking, was flown by his protégé, Ltn.d.Res Josef Veltjens. (Greg VanWyngarden)

At about 10:00 a.m. on the morning of Wednesday, 19 September, Oblt Rudolf Berthold attacked an R.E.8 on a photo reconnaissance flight east of Ypres and sent the two-seater down over German-held Becelaere. He was credited with his twentieth aerial victory.92 Only one R.E.8 – B.3427 of 4 Squadron, RFC93 – went down in that area; the crewmen were nineteen-year-old 2/Lt John Syers Walthew, whose body was not recovered, and Lt Michael Charles Hartnett, age twenty-one, who was buried near Jasta 18’s airfield at Harlebeke,94 a few kilometres north of Courtrai.

Even though he was, at last, flying and fighting in the active combat environment he seemed to crave, Berthold remained dissatisfied. He wrote in his diary:

‘As it was a year earlier, during the Somme offensive, once again we had to go into battle [in Flanders] with an inferior fighter aeroplane. The British and French continually improved theirs. They had already brought to the frontlines the third improved versions of their aircraft, however, our pilots are far better.’95

When the author visited Paul Strähle in May 1967, the former Jasta 18 pilot noted that his staffel leader was often given to wide-ranging mood swings. Strähle related:

“Berthold would fly into a towering rage over some small point and then, in an instant, be overjoyed with everything. Later, we learned that medical personnel were providing him with a narcotic for the pains he continued to suffer from his crash over a year earlier and the leg wound he received after that. At the time, such drug use was accepted, as we did not realise the effects of addiction caused by them.”

Fifty years later, when discussing Rudolf Berthold with this author, Oberst der Reserve a.D. Paul Strähle still had the Nieuport’s rudder as a souvenir of his fifth victory. (Kilduff Collection)

Ever since Rudolf Berthold’s bad crash in April 1916, he had complained of chronic pain. Suffering a gunshot wound a year later aggravated the condition and that is when he probably began to seek pain relief. World War I historian and physician Dr. M. Geoffrey Miller cited the 1915 Encyclopaedia of Medical Treatment when he told the author:

‘Three painkillers or narcotics were given at this time. These were morphine, given by mouth or injection; codeine, which is methyl morphine, given by mouth or injection; and opium, given by mouth. Morphine was used frequently and, of course, was addictive ... It was the main painkiller during the war ... but habituation and addiction to morphine cause constant somnolence [drowsiness]. The latter suggests Berthold used cocaine, which is likely to give mood swings and agitation. It causes increased activity and keeps one awake.’

Seven More Victories

During the successful days of September, Jasta 18’s older Albatros D.III fighters were replaced or augmented by improved Albatros D.Vs and new Pfalz D.IIIs.96 Irrespective of Berthold’s mood, during the next ten days of relentless effort, he increased his personal score. On Friday, 20 September, during ‘low clouds, strong wind and rain’,97 at about 9:50 a.m. German time (8:50 a.m. Allied time), while flying southeast of Ypres, Berthold attacked a single-seat fighter and shot it down between Wervicq and Menin. Due to the weather, the adversary was initially identified as a SPAD single-seater, but it may have been a similar Airco D.H.5. (A.9179) that was lost in that area. The aeroplane, from 32 Squadron, RFC, was described in a British report as ‘last seen about 9 a.m. when [the] machine was apparently hit by a shell from the ground98 and fell into our barrage ... pilot [2/Lt William Oliver Cornish,99 was] killed in action or died of wounds ...’100 Most likely, Cornish was Berthold’s twenty-first victim.101

Line-up of Jasta 18 pilots, from left: Ltn Hugo Schäfer, Ltn Richard Runge, Oblt Ernst Wilhelm Turck, Ltn Walter Dingel, Ltn.d.Res Josef Veltjens, Oblt Rudolf Berthold, Oblt Harald Auffarth, Ltn.d.Res Arthur Rahn, Ltn.d.Res Paul Strähle and Ltn Otto Schober. (Paul Strähle)

Other than its backward staggered wings, the rotary-engined Airco D.H.5 could be confused with other Allied fighter aircraft. (Volker Koos)

The weather improved throughout the following morning and Berthold was flying west of Menin when he encountered and shot down SPAD 7 B.3533 of 19 Squadron, RFC, and killed twenty-four-year-old 2/Lt Frederick William Kirby. At first, the victory was listed as ‘noch nicht entschieden’ [not yet determined],102 but after several weeks of reviewing numerous German victory claims, Kogenluft staff awarded Berthold official confirmation for it.103 As British airmen later recorded, their ‘high’ formation of six SPADs and two S.E.5s ‘suddenly encountered many [enemy] scouts ... [and] a general fight ensued ... Lieut. [Norman] McLeod ... thinks he saw fifteen enemy aircraft altogether in this fight.’104

On the morning of 22 September, Berthold and his patrol were over Ypres when they spotted British two-seaters in the area. Berthold went after one, a Bristol Fighter, an aircraft with a reputation for being ‘strong, fast and manoeuvrable’.105 Berthold avoided the pilot’s forward-firing gun and, after a short duel with the observer and his flexible machine gun, he shot down Bristol F.2B A.7205 of 22 Squadron, RFC, east of Zillebeke lake. Both crewmen – 2/Lts Elvis Albert Bell and Roger Emmett Nowell – were killed in the fight.106 It was his twenty-third victory.

During an early-evening patrol near Ypres on 25 September, a British fighter was making a dangerous low-level ground patrol east of the city. Amazingly, the aeroplane was unescorted – and vulnerable. Berthold dived on the single-seater and sent it down near Gheluvelt along the road from Ypres to Menin and thereby scored his twenty-fourth victory. His target, SPAD 7 B.3520 of 19 Squadron, RFC, was flown by nineteen-year-old Lt Bernard Alexander Powers,107 who paid the ultimate price for his devotion to duty. A squadron report stated: ‘A message was received that [German] troops were massing for an attack on the [British] 10th Corps front. Lt Powers, after studying the position on a map ... jumped into his machine (which had been made ready for him) and left the ground a ... few minutes after the message was received in order to fly over the sector of [German] lines in question and to try to bring back information. He did not return.’108

The French-built SPAD S.7, seen here in RFC markings, was used successfully by 19 Squadron and other British fighter units that Berthold encountered. (Volker Koos)

While British forces continued to advance east of Ypres on the morning of 26 September, a patrol of five Sopwith Camels from 70 Squadron set out on a low-level trench-strafing mission. 2/Lt C.G.V. Runnels-Moss later reported that ‘after firing [their] ammunition off, the machines returned toward our lines as fast as they could, but the formation was rather split up, and at one point [Runnels-Moss] turned to the north while most of the others went towards the south ... It is very difficult to make out what happened – in fact, we have no idea. It is possible that some enemy machines saw our patrol flying low and attacked it after its ammunition was all spent. At that height, a single shot in a vital part of any of the machines could force [it] to land in enemy territory.’109 2/Lt Runnels-Moss and Lt G.R. Wilson110 made it back to their airfield; the other three Camel pilots were reported as missing.111 One of the aircraft – B.2358 piloted by a twenty-four-year-old Canadian, Lt Walter Harvey Russell Gould112 – most likely was shot down and killed by Rudolf Berthold near Becelaere. It was his twenty-fifth victory.

At mid-day on 28 September, eight two-seat Bristol Fighters of 20 Squadron, RFC were sent on a photo reconnaissance flight over Menin, which was less than fifteen kilometres from Jasta 18’s airfield at Harlebeke. The British airmen reported encountering ‘about 25 Albatros scouts’,113 which included units of Berthold’s Jagdgruppe 7. Bristol Fighter crews claimed to have shot down two Albatroses, but Berthold’s men came through unscathed. In fact, three Jasta 18 pilots each claimed a two-seater. But 20 Squadron reported only two losses: Bristol F.2B A.7210 and the crew of Capt John Santiago Campbell and Private G. Tester;114 and F.2B A.7241 crewed by 2/Lts Harry Francis Tomlin and Harold Taylor Noble,115 all of whom were killed. Berthold claimed his victim south of Zillebeke lake, over British lines; Oblt Harald Auffarth gave a location of south of Wervicq, within German lines; and Ltn.d.Res Josef Veltjens stated east of Hollebeke, over British territory. None of these victories was announced in the regular September listing; rather, they appeared in an August-September supplement, issued five weeks later. All three Jasta 18 pilots were credited with a victory, Berthold with a Martinsyde (none of which were lost that day116), for his twenty-sixth victory, and his comrades each with a vaguely-defined ‘British two-seater.’117

Rudolf Berthold claimed to have shot down only one Sopwith 1F.1 Camel, of which a captured example is seen here. (Volker Koos)

There was a brief celebration and Berthold’s Albatros D.III was decorated with a wreath to commemorate his 25th victory. (Greg VanWyngarden)

Just before noon on 30 September, Berthold led a patrol that arrived over the lines in time to save a German two-seat reconnaissance aircraft under attack by a flight of Sopwith Pup single-seat fighters. An account of the fight appears in British records:

‘A patrol of 66 Squadron pursued a hostile two-seater when they were dived at by a [German] formation. The [British] pilots, though taken at a disadvantage, fought well and one of the enemy machines was destroyed by Captain [Tone Hippolyte Paul] Bayetto, while another was driven down out of control by Lieutenant [Walbanke Ashby] Pritt. Two of our machines were lost on the other side and two were forced to land in our territory, while several of the other machines were shot about, one coming back with a cylinder completely shattered.’118

German fighter units reported no casualties that day,119 but Jasta 18 likely accounted for the loss of the two 66 Squadron Sopwith Pups: B.2185 piloted by 2/Lt Joseph Gordon Warter,120 who was reported ‘coming down in a spin just south of Geluwe’ and was killed, and B.1768, flown by Lt J.W. Boumphrey, who was also last seen descending over Geluwe and was later reported taken prisoner.121

Once again, these two victories were not confirmed in the regular bimonthly Nachrichtenblatt listing and appeared in an updated accounting weeks later. When the Jasta 18 combat reports were sorted out, victory credit for shooting down ‘Sopwith single-seaters’ was granted to three pilots at different locations: Oblt Berthold at Deûlémont, his twenty-seventh victory; Oblt Auffarth at Wambeke and Ltn.d.Res Veltjens at Ploegsteert wood.122 The three crash locations are between ten and eighteen kilometres away from Geluwe, where the two British Sopwith Pups were last sighted. Present-day historians can only wonder how Kogenluft staff arrived at these determinations, awarding credit where due, and offering leeway to some pilots but not others.

Jasta 18’s September successes – all attained with no casualties to the unit – may have been so invigorating that they slightly inflated Berthold’s ego. On the last day of the month, Berthold’s diary entry gives a glowing account which is not supported by existing documentation:

The Sopwith Pup downed by Berthold on 30 September 1917 may have been repaired and ended up like the trophy seen here. Admiring this Pup was Oblt Fritz Otto Bernert, a Berthold comrade from their KEK Vaux days. (Volker Koos)

‘End of September 1917. Today is the fourth time that Jasta 18 has cleaned up in the unassailable force of the British bombing squadrons. My three Jastas brought down seventy-three enemy aeroplanes in September.’123

The Nachrichtenblatt report for that day showed relatively light British casualties claimed overall. Further, September victories for Berthold’s Jagdgruppe 7 tally only fifty-five aircraft and no captive observation balloons, as follows: Jasta 18 – thirty aircraft, Jasta 24 – ten aircraft, Jasta 31 – five aircraft, and Jasta 36 – ten aircraft.124

The flurry – to say nothing of the fury – of his six weeks at Jasta 18 may have taken their toll on Rudolf Berthold. He would never have admitted to such an unavoidable personal failing and continued to act as if his body were as iron as his will and totally invulnerable.