BEGINNING OF THE END

‘I am pleased to express my appreciation and gratitude for your fortieth victory in aerial combat ... We hope for new successes that will accrue to the glory of you and your branch of service and to the salvation of the German Fatherland.’1

GENERAL DER INFANTERIE JOHANNES VON EBEN

The German Luftstreitkräfte suffered a severe blow to its morale on Sunday, 21 April 1918. During a noontime aerial combat over the Somme sector, Germany’s leading fighter pilot – the eighty-victory ace Rittmeister Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen – was shot down and killed behind British lines. Many tributes were written and Richthofen was buried with honours by his foes. But Hauptmann Rudolf Berthold took the death of this legendary German as a personal loss, one he, again, felt compelled to avenge, even in the face of overwhelming odds. Written in his diary was this self-challenge: ‘Richthofen has fallen, comrades fall daily, the British have surpassed us; I must show young people that duty stands above all else.’2

Berthold willingly and eagerly tried to carry out that promise, even while continuing to suffer great pains from his most recent wounds. He described his misery, at times in great detail, in letters to his sister Franziska, to apprise her of his medical condition. Some years later she provided those texts to the German military writer Werner Schulze von Langsdorff,3 whose early research is the source of a letter dated 25 April 1918, describing a medical treatment Berthold required:

‘The evening of the [23 April], a bone splinter protruded from my lower wound. My very capable medical orderly came immediately with a pair of tweezers, and with much skill and force, he removed [it] ... by the light of day. I passed out during this violent procedure. The pains were horrific. But the lower wound is beginning to close. Only the upper wound still festers very heavily.

‘When the bone splinter was being withdrawn it broke into pieces, as the opening was too small and the splinter was snagged in the flesh, and so he had to probe and extract each piece. Out here one cannot ask for too much and my medical orderly believes that if we do not find a wound specialist, it would be pointless to consult with other doctors – as the orderly knows as much as they do about this problem.’4

In the same letter, Rudolf also shared other concerns with Franziska – worries that hinted at his precarious mental state:

‘I have so much worry and trouble, as I must let three staffel leaders go. It is a hard blow. Now that Richthofen is dead, I am the very last [Geschwader commander]. And instead of cooperation, one finds difficulties. It is ugly and wears one down. The staffel leaders had formed a sort of conspiracy to overthrow me. I will be ruthlessly hard. In the coming days, I want to fly again. The “boys” should be ashamed of themselves and I will get rid of these disruptive brothers. The death of Richthofen has been very depressing. Now I have to move on as one of the “old guard”. Maybe I will also be killed.’5

That letter was another by-product of Berthold’s increasingly black moods, which could have been caused by chronic cocaine usage. So it should be noted that, first, he was not the last (or only) air wing commander; Richthofen had designated a successor at Jagdgeschwader 1, Hptm Wilhelm Reinhard, to assure a smooth transition in the event of his death. Second, there is no evidence that Berthold’s leadership was ever challenged by his subordinates. For the most part, his men admired and even idolised him, despite his outbursts of temper and fits of loud swearing. And, third, there was no mass exodus among JG 2’s staffel leaders. Over the next three weeks, in the normal scheme of things, three of his four staffel commanding officers moved on to newer units that needed combat-experienced leaders.

Even though Rudolf Berthold did not fly during the first five months of 1918, he had a new Pfalz D.IIIa in readiness. Here, it is seen at right, at Balâtre Airfield in early April. (Greg VanWyngarden)

After learning of her brother’s continual severe pains, Franziska Berthold understood that he needed the pain relief offered by drugs, if even at the frightful personal cost of a descent into paranoiac delusion. To quote an entry in the diary she maintained for him:

‘Under his leadership, his Geschwader ... performed magnificently ... But his vigour was gone. The constant discharge from his wounds and the nerve pain wore down the body more and more. In order to work [in the air] and have inner peace again, he had to be given [drugs]. He would not relinquish his newly begun work, as he saw how every part of it was needed. His old faithful comrades were all dead or back home. The young ones no longer understood him and that, for him ... probably remained the greatest pain.’6

Not informed of his mental state, but very aware of his perverse desire to return to flying, Berthold’s superiors increased his administrative duties to keep him busy. On 8 May he was appointed to coordinate all fighter aviation within the 18th Army sector.7 But, when the second German drive (the Lys Offensive) also failed to achieve strategic success and was followed by a third drive (the Aisne Offensive), beginning on Monday, 27 May,8 Berthold could no longer stay out of the fight.

His units had soldiered on with rapidly aging Albatros D.Va aircraft that experienced wing design difficulties and Fokker Dr.I triplanes plagued by production problems, but the rugged tubular steel construction of the new Fokker D.VII biplane fighter offered German airmen the best hope of protecting their skies. Indeed, Berthold was so anxious to fly the aeroplane – even though technically forbidden to fly at all – that he borrowed one from JG 1. He liked the aeroplane very much and noted that ‘it flies very nicely. Above all, the control column is so light that I could work it even with my right arm.’9

More Berthold Victories

On the morning of 28 May, Berthold ordered his new Fokker D.VII rolled out at Le Mesnil (Nesle) Airfield for his first combat flight since leaving the hospital almost three months earlier. As he told his men during the pre-flight briefing: ‘We are not here to carry out cavalier aerial combats at 500 metres’ altitude. The infantry is out there in the mud, waiting for us, and we have to help them.’10 He and a patrol of Jasta 15 fighters headed southeast, toward the most active lines.

At about 11:15 a.m., Berthold and his wingman, nineteen-year-old Ltn Oliver Freiherr von Beaulieu-Marconnay, dived on a pair of French SPAD XVI two-seaters that were attacking German positions near Crouy, northeast of Soissons. Berthold wrote in a letter:

‘After a few shots, [my] opponent was finished ... The second was shot down by [von Beaulieu-Marconnay]. It is a ray of hope. Above all I have a better grip on my Geschwader and can tell the people at Kogenluft the truth [about my capabilities].’11

The two aircraft from Escadrille Sop 27812 were counted as Berthold’s twenty-ninth victory and his companion’s first.13

Despite having to fly in a heavy mist the following evening,14 JG 2’s pilots must have felt that ‘the old Berthold’ was back in action. Beginning at about 6:30 p.m., he scored a double victory, hitting first a SPAD XIII single-seat fighter and then a two-seat Salmson 2A2 reconnaissance aircraft15, which he described almost incidentally: ‘I shot down my thirtieth and thirty-first within ten minutes, one of them over his own airfield. I almost stayed over there ... as I shot up [my] propeller ...’16 The mangled propeller caused his engine to run unevenly. Berthold turned it off, glided away from his falling second opponent and made an emergency landing within forward German lines south of Soissons.17 He wrecked the Fokker D.VII, but suffered no injury to himself.

In late May, Berthold resumed combat flying in the first of several Fokker D.VII aircraft in markings that have since become iconic. (Helge K.-Werner Dittmann)

Berthold received a new Fokker D.VII a few days later and used it on the evening of Wednesday, 5 June. According to JG 2’s war diary, he shot down an Airco D.H.9 two-seater in flames near St. Just-en-Chaussée,18 less than twenty kilometres southwest of Montdidier. A British casualty report noted that a D.H.9 (C.6203 of 103 Squadron, RAF) was ‘last seen going down in spirals, attacked by four [German aeroplanes] over the woods between Warsy and Lignières, apparently under control.’19 After that sighting the aeroplane crashed and the crewmen, Capt Henry Turner and 2/Lt George Webb,20 were found dead. The D.H.9 was recorded as Berthold’s thirty-second victory. 21

Even though very successful at this point, Rudolf Berthold relied on drugs to an obvious, but discreetly mentioned, extent. Nineteen-year-old Ltn Georg von Hantelmann of Jasta 15 mentioned it to his sister, Anna-Luise, who later wrote about Berthold:

‘He had [the use of] only one arm, so his skill was all the more admirable; but he sought physical relief from pain through the use of morphine [more likely cocaine], which unfortunately often made personal dealings with him very difficult. So, despite the great respect that was accorded to him, he was not very popular in many instances.’22

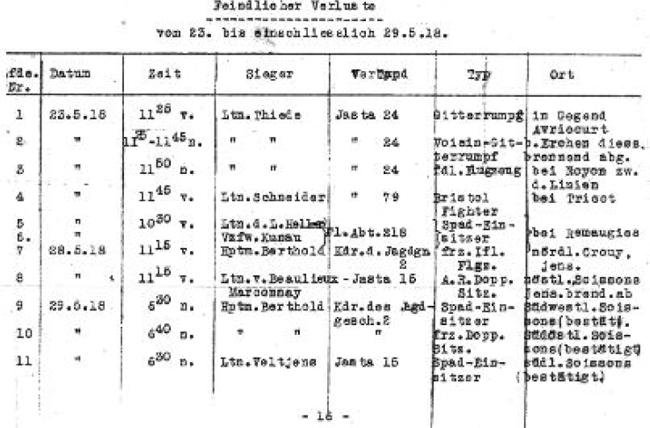

Berthold’s double victory of 29 May 1918 was included in the 18th Army Air Commander’s weekly report. (Kilduff Collection)

An Airco D.H.9 in the markings of 103 Squadron, RAF, showing a crew that could have faced Rudolf Berthold on 5 June 1918. (Cross & Cockade International)

But the course of the war overrode all other considerations. As part of the fourth German drive (Noyon-Montdidier Offensive), on 9 June, General der Infanterie Oskar von Hutier’s 18th Army ‘attacked from the Noyon-Montdidier sector... [but] were soon stopped by French counter attacks.’23 JG 2 aircraft were in the middle of this fierce battle and fought against a variety of Allied aircraft in hopes of helping to sustain the German advance. On Tuesday, 11 June, Berthold shot down a low-flying two-seater in the sector, while his comrades fought with British Sopwith 1.F1 Camels that were protecting the ground strafing aircraft. Confirmed as Berthold’s thirty-third victory, in the heat of battle, it was identified only as a ‘French infantry support aircraft’.24 It was one of several brought down that day by Berthold’s Geschwader.25

The following day, 12 June, German forces anticipated a French attack from Compiègne to their south and, while good weather held in the morning, JG 2 aircraft were out and scored three victories. A rainy afternoon curtailed flight operations and the airmen of Jasta 15 were confined to their Kasino at Mesnil-Bruntel Airfield. It was still raining at about 6:00 p.m., when Hptm Rudolf Berthold appeared in the doorway and announced:

‘Meine Herren [gentlemen], get ready! The staffel takes off in ten minutes. I will lead. At the frontlines, northwest of Noyon, French bombers are pounding our artillery positions to smithereens and we are sitting here, drinking coffee. The weather is bad, so if the staffel becomes separated, each one of you will attack individually. I ... do not need to tell my flight that each of you will remain at the frontlines until the last drop of fuel [is expended]. The enemy advancing on the ground is also a worthy target.’26

Each pilot knew he had enough fuel for eighty minutes of flight time, according to Ltn Joachim von Ziegesar, a member of this flight.27 Over the battlefield, there was a wild mêlée of German and French aeroplanes chasing each other through the mist. Berthold was seen attacking several adversaries.

After an hour into the flight and with only twenty minutes’ of fuel remaining, the patrol formed up to return home. But then von Ziegesar saw Berthold go after another French aeroplane. The others waited briefly, but, with only ten minutes’ of fuel left, they flew back to Mesnil-Bruntel. They landed with nearly dry fuel tanks. There was no sign of Berthold and an anxious time began, as von Ziegesar later wrote:

‘We sat awake for a long time. Nobody thought of going to sleep without knowing, for certain, the fate of our leader. Finally a furiously angry telephone call comes in the early morning hours [of 13 June]. Hauptmann Berthold vanquished his opponent and, with an empty fuel tank and his machine all shot up, he landed within the lines of our forward infantry units.’28

The daring landing and the damaged aeroplane meant little to Berthold, who the following day wrote to his sister:

‘Today, unfortunately, I cannot fly, as my engine was riddled with bullets in an aerial combat yesterday. The “boys” have plucked me clean in recent days. There were always too many of them. I shot down my thirty-third opponent … out of a [flight of a] hundred enemy aircraft …I have never seen so many opponents at one time ...’29

Berthold’s target was most likely a SPAD XIII of Escadrille Spa 96 flown by twenty-one-year-old Caporal [Corporal] Jacques Monod, who was badly wounded in the fight and died the following day.30

Vfw Albert Haussmann of JG 2’s Jasta 13 posed with a French SPAD XIII of Escadrille Spa 89. (Volker Koos)

On Tuesday, 18 June, Berthold scored his fourth double victory, but it received brief mention in a letter to his sister a day later:

‘Today we have rain. Thank God, for otherwise it would have been impossible for me to fly with [the Geschwader]. My arm has worsened. Beneath the still open wound it is … badly swollen and inflamed. I think the bone fragments are forcing their way out, as the cyst that formed is quite hard. The pains are just awful. Yesterday, during my aerial combat, in which I shot down two British single-seaters in flames, my thirty-fifth and thirty-sixth victories,31 I screamed loudly in pain ...’32

Capt John Steele Ralston, MC, an American pilot attached to 84 Squadron, RAF, was in that fight over Villers-Bretonneux. According to his combat report, at about 10:55 a.m.:

‘I observed one formation of four E.A. approaching from the east a few hundred feet above, and one flight of about five E.A. at around 1,000 feet below. I concentrated on those above and when they dived I swung ’round, but was only able to drive off one of three which attacked Lieut. Nielsen, who was flying on my left rear...’33

Surely, Ralston saw Rudolf Berthold among the German fighter pilots attacking Lt Peter Nielsen in an S.E.5a (C.1923). It is likely that the JG 2 commander shot down Nielsen, who was last seen ‘in combat with two E.A. northeast of Abancourt’, as well as a second S.E.5a (D.259) flown by 2/Lt Robert Joss Fyfe, ‘southeast of Abancourt’,34 and was credited with their destruction. Both men died.35

Following that victory, Berthold was out of action for over a week. He simply needed a rest. After nearly four years’ work with battlefield casualties, his sister had gained great insight into combat-related wounds and she blamed the military establishment for her brother’s continuing service as a fighter pilot. She wrote: ‘... when [his] name surfaced repeatedly, no army dispatch reported that in the victorious aircraft sat a sick man, who operated his aeroplane with his left hand, with his mouth and with his feet.’36

Clearly, Rudolf Berthold was not operating any part of a Fokker D.VII with his mouth but his sister’s bitter hyperbole is understandable. She may have felt that he functioned as an aerial automaton, showing no emotion and reacting only to physical pain. But when he wrote to Franziska, he probably wanted to spare her grim details of combat and comment only on his medical condition, as seen in his letter of 28 June:

‘Yesterday I flew again for the first time since shooting down my thirty-sixth opponent and have since shot down my thirty-seventh in flames. The arm is still not good. Since the lower wound has opened up again, the pain has subsided a bit and the swelling has gone down. I have screamed in pain, sometimes frantically. It seems to have been only a bone splinter ... I know that every pain hurts at least two or three times as much since I was wounded because I have not had time to get my body back to its old robustness. And ... of course, the war has greatly sapped my strength. But I must persevere, no matter what the cost. After the war, we can slowly bring the old bones back together again.’37

Berthold’s thirty-seventh opponent was a Bristol F.2B (C.935), which he sent down out of a formation of two-seat fighters from 48 Squadron, RAF. The British patrol claimed destruction of several of the ‘twenty Fokker biplanes’38 that attacked it and observed that two of its own aeroplanes fell in flames during the fight. Berthold’s victims were most likely twenty-eight-year-old Lt Edward Alec Foord and Sgt Leonard James, age twenty, both of whom were killed.39 There were no JG 2 losses that day.

A Death in Berlin

Early July was a relatively quiet time for Jagdgeschwader 2 and Berthold was able to leave the frontlines to attend the latest Typenprüfungen [aircraft type tests] held at an airfield in Berlin and administered by the Flugzeugmeisterei [aircraft test establishment].40 Beginning on Wednesday, 3 July, the tests enabled competing fighter aircraft manufacturers to have their new models test flown by some of Germany’s best fighter pilots. Berthold was accompanied by Ltn Walter Dingel, a valued comrade from their days together in Feldflieger-Abteilung 23 and now JG 2’s technical officer.

The tests got off to a bad start, however, when the Zeppelin-Lindau D.I prototype fighter41 lost the top wing in a dive and crashed. The dead pilot, Hptm Wilhelm Reinhard, had succeeded Manfred von Richthofen as commander of JG 1.

While Berthold was in Berlin, Jagdgeschwader 2 was preparing for a brief move from the Somme sector to the Champagne sector. Berthold arrived at the new airfield at Leffincourt, northeast of Reims, in time to greet Luftstreitkräfte Commanding General Ernst von Hoeppner, who inspected area aviation units on 13 July. The following day, the 3rd Army’s air commander, Hptm Hermann Palmer, Berthold’s old boss in FFA 23, visited Leffincourt to discuss deployment of fighter aircraft42 during the fifth German drive set to be launched on 18 July.43 But the last German drive – also called the Aisne-Marne Offensive – came too late to stave off ultimate German defeat.

A Salmson 2A2 of the type shot down by Berthold on 19 July. The aircraft shown was from the American 1st Aero Squadron, which Berthold would subsequently engage. The unit marking, aft of the observer’s station, was a US flag. (Colin Owers)

JG 2 had hardly arrived at the 3rd Army sector, when, on the second day of the offensive, half of its units, Jastas 15 and 19, were deployed westward to provide air cover for the 7th Army. Berthold’s other two units, Jastas 12 and 13, covered the 1st Army.44 German ground and air units had to re-deploy quickly in the face of a stiff American, French and Italian counter attack. Berthold flew with Jasta 15 and added to his victory score on 19 July, when he shot down a Salmson 2A2 two-seater from Escadrille Sal 40 over Soissons. He killed the pilot, Capitaine Henri Denis, but the observer, Lt Chappius, managed to land the aeroplane and survive.45 Berthold was credited with his thirty-eighth victory.46

On Saturday, 20 July – amidst a record-making 100 combat flights carried out by JG 2 – Berthold scored his thirty-ninth victory; he shot down what was described as a ‘SPAD two-seater southeast of Dormans (Marne).’47 French records show no such SPAD casualty, although several other two-seaters were lost48 and Berthold’s victim may be among them. But victory came with a price that day. His aeroplane was badly shot up and he was forced to land at St. Gemme, north of Dormans, in the 7th Army sector. A newly-arrived subordinate, Vizefeldwebel Gustav Klaudat, was directed to fly his own Fokker D.VII to the stranded Geschwader commander, so the ‘boss’ could return to Leffincourt. But on landing back at his own airfield, Berthold flew into turbulence so strong that it flipped his aeroplane over and totally wrecked it. Luckily, Berthold emerged unhurt but another new Fokker D.VII was lost.49

Four days later JG 2 moved again, this time from the 3rd Army to Chéry-lès-Pouilly Airfield, north of Laon, in the sector of the newly reconstituted 9th Army.50 As a parting gesture, the 3rd Army’s commander-in-chief, Generaloberst Karl von Einem, issued a command-wide citation commending JG 2’s role in the recent battles and noted, in particular, Berthold’s most recent victory.51

A day later, unbeknownst to Rudolf Berthold, he was highlighted in the French weekly aviation magazine La Guerre Aérienne Illustrée as one of Germany’s highest-scoring living fighter aces. It is a tribute to Allied intelligence gathering that the publication listed Berthold’s score as thirty-eight confirmed victories,52 a level he attained only six days before the magazine appeared in news kiosks.

The pilot of Berthold’s likely 40th victory, lst Lt William P. Erwin (right), poses with another observer, 1st Lt Arthur J. Coyle, by a Salmson 2A2 of the 1st Aero Squadron, USAS. Erwin was uninjured in the fight and made it back to Allied lines. (Clifford E. Andrews Collection via NMUSAF)

On the fourth anniversary of the beginning of World War I, Thursday, 1 August 1918, Hptm Rudolf Berthold achieved his fortieth aerial victory.53 He had equalled the tally of his pre-war flying school comrade and the first aviation Pour le Mérite recipient Hptm Oswald Boelcke. It was JG 2’s only victory that day and was listed as a ‘French two-seater’ that went down ‘northeast of Château-Thierry, near Fère-en-Tardenois (on the other side of the lines).’54 Most likely, Berthold’s opponent was from the 1st Aero Squadron, US Air Service, which reported that one of its Salmson 2A2 photo reconnaissance aircraft flying in the area was involved in ‘heavy combat with Fokker D.VIIs, [which was] shot up [and] forced to land.’ Of the two American crewmen, First Lieutenant William P. Erwin was uninjured and First Lieutenant Earl B. Spencer was wounded in the fight.55

Two days later, General der Infanterie Johannes von Eben, commander-in-chief of the 9th Army issued a citation that surely validated Berthold’s sacrifices and appealed to his innermost vanity:

‘I am pleased to express my appreciation and gratitude for [your latest] and fortieth victory in aerial combat. The 9th Army views with pride the most capable combat flyer who at this time battles in its ranks and in its service. We hope for new victories that will accrue to the glory of you and your branch of service and to the salvation of the German Fatherland.’56

But it seemed that no amount of valour could forestall relentless Allied attacks on hard-won German gains. Eliminating or at least reducing three German salients improved: ‘lateral railway communications along the Allied front and facilitated future operations.’57 The attack on the last such salient, at Amiens, led to a ‘great Allied victory [which] caused [German General Staff Chief Erich] Ludendorff to call 8 August 1918 the “black day” of the German army, since, for the first time, entire units collapsed.’58

Amidst reports of ‘heavy clouds and mist along the entire [Western] Front’ on 9 August, the daily Nachrichtenblatt heralded the role of Germany’s leading fighter aces in responding to the jarring events of the previous day. That day’s chronicle noted that, among others: ‘Oblt Loewenhardt attained his fifty-second and fifty-third [victories], Hptm Berthold his forty-first and forty-second, Ltn Udet his forty-eighth and forty-ninth …’59

Flying with Jasta 15, at about 6:00 p.m., Berthold shot down an ‘enemy two-seater’ near Fricourt. It crashed south of Montdidier, which was a focal point of the French advance that day. Half an hour later, Berthold downed another two-seater near Beaucourt-en-Santerre, some twenty-five kilometres north of his previous triumph. His opponents were, most likely, a pair of SPAD XVI reconnaissance machines from Escadrille Spa 289, based at Poix-de-Picardie,60 west of the second fight. The two crews perished.61

A German source reported that ‘under varying cloudiness, [there was] heavy activity over and on the broad battlefield’ on Saturday, 10 August.62 Jastas 12, 13 and 15 took off for the frontlines and soon found a large and concerted British raid going on against ‘the stations at Péronne and Equancourt on the Bapaume-Epéhy railway.’63 The fifteen German aircraft were vastly outnumbered, facing twelve D.H.9 two-seat bombers from a combined force from 27 and 49 Squadrons, RAF. The bombers were escorted by a mix of S.E.5a single-seaters from 32 Squadron64 and Bristol F.2B two-seaters from 62 Squadron, which were later joined by seven S.E.5as from 56 Squadron.

A pilot from 32 Squadron, 2/Lt John Owen Donaldson, referring to himself in the third person, reported that that he:

‘... observed nine Fokker Biplanes, at 13,000 feet, over Péronne, at 11:30 a.m., dive on three S.E.5s. Pilot [Donaldson] came to their assistance, fired 150 rounds into first E.A. at close range, E.A. turned over on its back, and went down in a flat spin ...

‘Pilot observed Lieut. Macfarlane fire at one E.A., and saw it fall side by side with the E.A. shot by pilot, [from] about 10,000 feet.’65

Lt Peter Macfarlane in S.E.5a C.8838 probably shot down one of three Fokker D.VIIs hit in that fight; all landed within German-held territory and suffered no loss of life. But then Lt Macfarlane was shot down, very likely by Rudolf Berthold, as his forty-third victory was confirmed as a ‘British single-seater that went down in flames’.66 It crashed near Licourt, south of Péronne but Macfarlane’s aircraft was not recovered; consequently, he has no known grave.67 The other S.E.5a lost in that fight, D.6921 piloted by Lt William Ernest Jackson,68 went down southwest of Péronne, and was confirmed as the second victory of Ltn.d.Res Hans Joachim Borck of Jasta 15. According to British records, Lt Jackson survived his crash and was rescued, uninjured, by forward area French troops.69

Turning away from the falling S.E.5, Berthold spotted a D.H.9 bomber and went after it. The British two-seater crew resisted fiercely, but after ten minutes they were finished. The JG 2 history notes that Berthold’s last glimpse of the bomber – his forty-fourth and final aerial victory70 – was the dust cloud it kicked up as it hit the ground.71

Then, while surveying the hits to his own aircraft, Berthold was horrified to see how effective the British observer-gunner had been. One of the Englishman’s shots had severed the Fokker’s control column and, when Berthold tried to pull the aeroplane upward, he held only the top part of the now useless handle in his hand. He was at 800 metres’ altitude and quickly heading for the ground.

For a split second it must have seemed like the end to Berthold. Then his basic, cool-headed military discipline prevailed. His aeroplane was equipped with a static line-activated parachute, but that life-saving device required two hands to operate and Berthold’s paralysed right hand could not help him in this crisis. At 600 metres, he tried to level off using the controls that still worked. But he continued his downward rush. Then, a village came into view and momentum carried him just over the rooftop of one house – and straight into another house. The Fokker hit with such force that the engine tore loose from its mountings and plunged right down to the cellar.

Rudolf Berthold had come down in Ablaincourt, close to where the D.H.9 had crashed. Nearby German soldiers pulled him out of the rubble. Like his last opponents – 2/Lt H. Hartley and Sgt O.D. Beetham of 49 Squadron, RAF72 – Berthold was still alive, but wounded.73 Then he fell into unconsciousness.

He awoke at Feldlazarett 10 in the 2nd Army sector. Army doctors were amazed that he survived. But his, still unhealed, upper right arm bone was broken again and at the old fracture site. No one in the field hospital had the courage to tell Berthold that his air combat days were over.

Berthold’s 44th and final aerial victory was an Airco D.H.9, the type seen here. (Volker Koos)

As it turned out, 10 August 1918 was a disastrous day for German fighter aviation. In addition to Rudolf Berthold’s injuries, the Luftstreitkräfte marked the loss of the fifty-four-victory ace and Jasta 10 leader, Oblt Erich Loewenhardt, whose Fokker D.VII collided with a staffel-mate’s; Loewenhardt attempted to use his parachute, but it malfunctioned and he fell to his death.74 And Ltn Paul Billik, a thirty-one-victory ace who commanded Jasta 52, was shot down and taken prisoner that day.75

But Berthold clung to the hope of flying again. To emphasise the point, on the evening of 12 August he showed up at Leffincourt Airfield. With his usual air of entitlement, Berthold had persuaded a driver at the field hospital that he needed to return to JG 2 to resume his responsibilities. Once inside Jasta 15’s pilots’ mess, he announced: “Here, I am the boss.” The newly-appointed Geschwader commander, Rittmeister Heinz Freiherr von Brederlow, who had seniority and administrative experience, but only one victory to his credit, reportedly ‘acquiesced and left’ the room. Berthold said he would return to bed and give orders from there.76

He was so convincing that the Geschwader war diary entry for the day noted:

‘The Berthold luck has proven itself once again. He is under the care of one of Professor Bier’s assistants, who is at Kriegslazarett 19E in Montcornet, and will spend his recovery time here.’77

The next morning, however, Berthold’s condition worsened. He ran a high fever and was wracked by excruciating pains. A doctor was summoned and he ordered the wounded ace sent back to Montcornet – over fifty kilometres away – immediately. Given Berthold’s high visibility within the Luftstreitkräfte, news of his latest escapade travelled quickly and to the highest levels. Upon hearing it, ‘der Oberste Kriegsherr’78 [supreme warlord – Kaiser Wilhelm II] ordered swift action to prevent a recurrence. On 14 August, the commanding general of the Luftstreitkräfte sent a telegram to JG 2 staff officers at Leffincourt to clarify how Berthold’s future convalescence would progress:

‘The commander of Jagdgeschwader 2, Hauptmann Berthold, is to submit to official orders to be conveyed immediately in hospital care and is to remain there until properly discharged. Confirmation of the name and location of the requested hospital is to be wired [to Kogenluft] via the commander of aviation, 9th Army. Geschwader leadership will be assumed by Leutnant Veltjens until further notice.’79

The officer in charge of 9th Army aviation, Hptm Genée, a pre-war flyer and early wartime unit commander,80 was not susceptible to Berthold’s charms. He would assure these orders were carried out to the letter.

Two days later, on Friday, 16 August, Berthold protégé ‘Seppl’ Veltjens assured that his mentor was made comfortable on a train that took him from the battlefield rear area in France to the quieter and more accommodating Viktoria-Lazarett Universitäts-Klinik in Berlin.

Germany’s deteriorating war effort was rapidly losing heroes and needed to retain its older renowned veterans for propaganda purposes, if not for humanitarian reasons. For the foreseeable future, Rudolf Berthold’s battles would be against his own impatience and self-dissatisfaction while he continued to nurture impossible dreams of further glory.