TWO

Little Dorothy, Little Shirley

So here we were, Polly, Robert and me, living in Bexhill, just a couple of miles westward along the coast from my home town, Hastings, where I had lived for the first eighteen years of my life.

I know I have a good memory, after all I can remember the words of a few hundred songs. But I wonder, how truly personal are those earliest memories, are they really mine or are they what have been recounted to me by my parents and grandparents?

But I'm sure I remember the Christmas (I was probably three or so) when we still lived in our ‘old’ house on Emmanuel Road, on the West Hill, Hastings. I'd been so excited to get a china doll as a Christmas present that I tossed it up and up in the air. I was told to stop, warned that it would break if I dropped it; but I couldn't stop, and of course it fell and smashed on the lino floor. I can see myself at the age of four, rummaging in the neighbours’ dustbins for discarded flowers, then trying to sell them from door to door. Another time, I persuaded the assistant in the shoe-shop on the corner of the next street that my mother said I could have the pair of blue shoes that I'd spotted in the window display, and coveted. She let me take them away, but soon followed after me to ask Mum (Dorothy Florence Collins) if this was the case. It wasn't, and the shoes were taken away again. But how, I wonder, did I get out of the house? I don't think my mother was careless or unwatchful. In a notebook of hers that I found after she died, she had written some of her memories down, and it said that I'd open the front room window, climb out onto the sill and fall down into the garden. Soon after this, Dad (George Leonard Collins) nailed the window shut!

I have a photograph of me at perhaps a year old, sitting on the grass in our unkempt back garden, scowling at the sun. We had a tortoise called Fu; I was fascinated by how slowly he blinked his eyes, how deliberately he munched and gulped lettuce leaves, and how he appeared to move his legs sideways and backwards in order to move forward. We had a large ginger cat, Mickey, that Dad had brought back as a kitten from a farm, a gift from a customer on his milk round. Mostly he was given dead rabbits, so this made a nice change and Mickey stayed with us for fourteen years.

I can still recall the smell of the savoury braised heart that Mum cooked when Granny and Grandad came down on Friday evenings for supper, followed by a game of cards. My sister Dolly and I sat on either side of Grandad begging for tastes.

At our infants’ school on the West Hill, we always had a nap after lunch, lying on the floor on individual oval rush mats – no complaints from any of us how hard they were, just obedience to the ritual. It was a pleasant and sensible thing for pupils and teachers. It worked in schools then, so why not nowadays? Why has time become so compressed?

I just about remember my great-granny, Mary Ann Easton, who lived on the top floor of our tall house (or so it seemed to me), at the top of dark stairs which we had to climb up to visit her. She's important to me as it was she who sang ‘The Cuckoo is a Pretty Bird’, which was one of the songs I sang on my album Sweet England (1958) recorded by Alan Lomax and Peter Kennedy. I have a clear picture of her, however, only from her presence in the photograph of my parents’ wedding. She was tiny, shaped like a bell, in her long, full skirts with a high toque hat and dressed entirely in black ever since she had lost her son George Cyril Easton (my mother's uncle) in the First World War. He served in The Royal Flying Corps, and was shot down over Italy on 5 August 1918 aged eighteen and a half. At first he was reported missing, but the story came down through the family that on that night his mother awoke to see her son standing at the foot of her bed. He said to her, ‘Don't worry, mother, I'm alright’. Then he turned to the door, waved a hand in farewell and raised his head; his mother saw that it was a skull. Next day the telegram came telling of his death.

I have the bronze plaque his parents were presented with after the war, a beautiful thing in its way, with Britannia holding her trident in one hand, and an olive wreath – or is it a laurel wreath? – in the other, a lion padding at her side, and with two leaping dolphins circling around her. HE DIED FOR FREEDOM AND HONOUR is inscribed around it, and it's set in a solid wooden circular frame. The letters that form his name are a little rubbed, and I picture his mother touching them over and over. When I hold it, I feel such pity and anger for her, and for the many thousands of other grieving mothers, wives, sisters and sweethearts, and wonder how they found the courage to endure their losses. I also have the memorial book that Great Granny made for him, full of cuttings and verses from newspapers and magazines – such sentimental platitudes, and such hypocrisy it seems to me now – though not on her part. It must have been a consolation for her, a comfort, albeit, surely, a bitter one. On the first page is this from a local newspaper:

WAR CASUALTIES – 2nd Lieut. George Cyril Easton R.A.F. was reported missing on 5th August, and no further news has been received. Lieut. Easton was a boy in our choir; he has done well, and thoroughly deserves the position he has won for himself in the army.

Deserves what?! Lying dead somewhere in Italy, shot out of the air!

His mother placed these words in the local paper: ‘In loving memory of our only son Lieut. Easton R.A.F. killed in the air on August Holiday 1918.’ All deaths in this conflict were unbearable, but somehow it seems extra cruel to lose your child so close to the end of the war.

There was such pride in him at first. He had, unsuccessfully, tried to join the army when he was sixteen; his father followed him to the recruiting office and hauled the under-age boy home. But at eighteen he successfully enlisted. Although but an under-gardener, his natural intelligence was noticed, and he was sent for a short while to Oxford University. As his nephew Fred FC Ball sardonically wrote, some 45 years later, in his book A Breath of Fresh Air:

What had happened was that the war had got in a tangle and the government had decided, to the dismay of some regular officers, that certain men from the ranks should be commissioned. So Lance-Corporal Uncle Cyril was interviewed to see whether he could be taught to speak an officer's version of the King's English. And, needing a little practice, had been sent to Oxford University for three months as a cadet in the Royal Flying Corps.

Great Granny survived until 29 January 1938, missing, mercifully, yet another world war; so I would have been two and a half when she died. My memories of her are faint now; all I can recall is the tiny celluloid bath with metal taps she gave me one Christmas, with a celluloid doll and a scrap of cloth for a flannel. I never knew her husband, George Easton, who had died before I was born. My mother told me he had been a builder and decorator, part-owning the business until his partner made off with all their money. He then had to join the work force and at one point had a job at the Woolwich Arsenal, ‘helping to make widows and orphans.’ He had been a lay preacher, but his troubles ruined him financially, and led him to drinking heavily. He became increasingly irascible, disgusted with the social set-up, and deeply affected by the loss of their son in the Great War; they received a small pension for this – he called it ‘blood money’. They had to move from their rented house into two rooms, and from there into one room and were evicted even from that because of his temper. Uncle Fred remembered him as a fiery man, and a cynic: ‘A cynic is a man who takes comical things seriously, and serious thing comically.’ George died in 1931 following a fall in the street in which he broke his hip, and at this point my parents, newly married, gave his widow a home and took care of her.

My own maternal grandparents I remember clearly. I see Grandad drinking his tea from a saucer. Of course, it was given to him in his large special cup, and he'd pour it into his saucer, blow on it and slurp it into his mouth. But when Dolly and I attempted to follow suit, it was forbidden. He had his own knife, with which he did everything from whittling wood to cutting cheese – always with the knife blade towards him, as did Granny when slicing a loaf of bread held against her pinafored bosom. Our favourite trick of Grandad's was peeling an apple in one go, ending up with a beautiful long curling peel – if it was intact you could make a wish. He held his thumb against the back of the blade, which was worn to a sliver; it was a knife he had used for a very long time.

We were given tasks by our grandparents. With Granny, we helped cut apple rings and thread them on string to be hung up in her scullery to dry; we trimmed runner beans from Grandad's garden to salt away in big stone jars, but we also had to scrape the big blocks of salt – and that was painful. You couldn't help grazing your knuckles and you couldn't keep the salt from them. Grandad grew tobacco in his greenhouse, and we'd help him slice the leaves as finely as we could before packing them into bowls to have black treacle poured over them – he called it a sweet-cure! We'd sit and watch while granny darned our socks over her wooden mushroom, and patiently help unravel old jumpers, winding the wool into balls ready to knit scarves and mittens. We loved them both absolutely. Every Christmas we'd buy Grandad a small pot of Gentlemen's Relish, the rather expensive (we thought) anchovy paste. How could anyone like anything so salty and fishy! And Granny's Christmas treat was pickled walnuts – even the tiniest nibble gave me heartburn. What odd creatures grown-ups were. Still, Granny did always have a glass jar of striped mint humbugs on hand.

I was fascinated by the way Granny did her ironing; she'd cover the kitchen table with a blanket that was mottled with scorch marks, wrap a wad of cloth around the handle of her flat iron and heat it on the kitchen range, testing its readiness by spitting on the iron until it sizzled. We children were forbidden to spit… another example of what adults could do, but children mustn't. In our house, Mum plugged her electric iron into the light socket overhead. No wonder she was nervous of electricity – much like Thurber's cartoon of his Grandmother worrying about it leaking all over the place!

I've often told of my grandparents singing to Dolly and me as we lay in their Morrison shelter during World War II. Grandad sang a couple of songs – ‘The Bonny Labouring Boy’ was one of them. Granny sang ‘Barbara Allen’ and mostly sentimental Victorian or Edwardian songs… What were we supposed to make of these songs I wonder now? There was one about two little girls – one rich, one poor. The two of them are sitting under a tree, and the rich girl, whose daddy is a gentleman, mocks the poor one because her daddy is clearly not.

And that's all I remember until the verse when, as the little rich girl is about to get run over by a carriage, the poor girl's father dashes into the road, saves her, is crushed by the horses and dies… and the last chorus, sung first by the rich girl goes:

And the poor girl…

Then the other girl replied ‘God bless you!

So that's alright then…

The other memorable cheery song of Granny's had a chorus that ran, ‘For we all must die like the fire in the grate.’

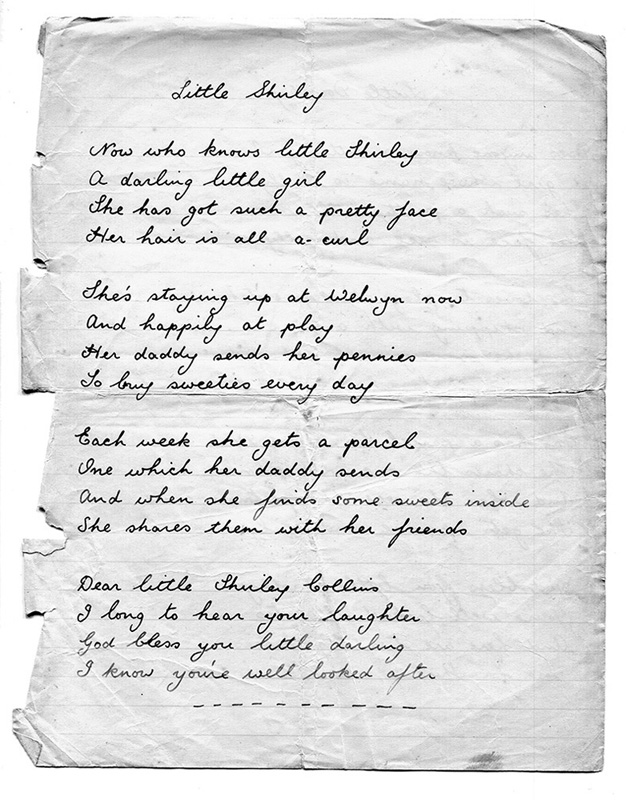

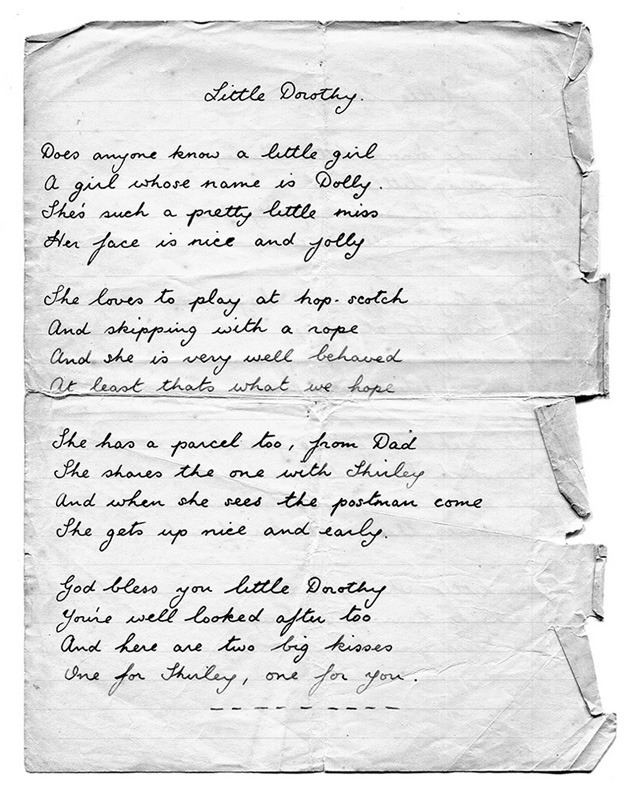

My Dad served in the Army in the Second World War, and while he was gone, Dolly and I were evacuated from Hastings to Welwyn Garden City – the whole primary school was sent, with our teachers, but without Mum. I have a rather touching photograph (opposite) of Dolly and me in our wellington boots taken in the school playground at Welwyn; Dolly has a protective arm around my shoulders, and an anxious smile on her face. Obviously, we have both been told to stand up straight – our arms are held firmly at our sides! Mum said that she and Dad came to visit us once, when he was on leave, but I have no memory of it. What I do have, from a book of poems written by him while on active service, are these two simple verses; doggerel, if you will, but I treasure these pages written in Dad's hand, the paper now dog-eared and foxed.

The entire system of evacuation seemed chaotic to say the least, for the extraordinary thing was that soon after we were taken away, Mum was sent two evacuees, young boys from London's East End. They were so impressed when Mum cooked fish and chips, as they'd only ever had shop-bought. They arrived with fleas, and in the following years Dolly and I would sit patiently on Sunday evenings our heads bent over newspaper, while Mum worked through our hair with a fine-toothed flea comb, just to make sure. We were away for just a few months before being returned to Hastings, united with Mum again. Not long after this we were evacuated, this time with Mum, to Llanelli in Wales for a few weeks. But soon after we had been sent back to Hastings again, an incendiary bomb hit the house next door on Emmanuel Road and took half of ours with it; luckily we were out at the time.

So Mum, Dolly and I moved up to 27 Canute Road in Ore village to share Aunt Grace and her husband Cyril Winborn's home, with their children Bridget and Lesley. Their railings and iron front gate had long since been officially requisitioned ‘to help with the war effort.’ We weren't free from bombing or strafing raids from German planes. Many nights we slept in the broom cupboard under the stairs on eiderdowns; three children, a baby and two adults (Uncle Cyril was in the Fire Brigade and out on duty most nights). The front door was blown in by the blast from a bomb that landed two streets away and brought down our ceilings, covering us with plaster. Dolly and I were strafed one day as we walked down Alfred Road pushing baby Lesley in her pram. We saw a huge grey plane coming straight up from the sea, realised as we saw the black cross on the underside of its wings that it was German, and flung ourselves, and the pram, under a hedge, and watched machine-gun bullets tear up the road.

Uncle Cyril had been a snob – a cobbler – in civilian life and still had his iron last. He mended all our shoes, paring away the leather on the soles, his thumb firmly pressed against the blade of the knife, and hammering in the blakeys, the metal studs that made your shoes last that bit longer, which also were great for striking sparks on hard pavements. He made sure our shoes were polished, too. He kept rabbits in hutches in his side garden; we loved playing with their soft ears. Aunt Grace was a very good cook; she'd gone into service at fifteen, and had risen from maid-of-all-work to become cook over the years. She could conjure meals out of very little; she made the lightest pastry and her rabbit pie was memorable. Wartime, with its food rationing, was not the time for sentiment.

So deprived were we of sweets during the War that one day, when I spotted a bar of chocolate on the mantelpiece, I took it and ate it all. The theft was discovered, and retribution was speedy; it turned out to be a bar of Ex-Lax – yes, the laxative. When things had calmed down, Mum stood me in a corner with a piece of cardboard tied round my neck with the word THIEF written on it – a double humiliation. I didn't quite learn my lesson though. That punishment was repeated when I polished off a half-full tin of sweetened condensed milk that I found in the larder, and which the grown-ups were saving to sweeten their tea. We weren't punished often; just the threat of ‘a clump’ or a ‘thick ear’ would sort us out. The worst was being sent to bed without any supper, although generally Mum relented and would bring up a bowl of ‘bread-and-milk’, cubes of white bread soaked in warm sweetened milk. Very comforting. There were so many things to be alarmed about, too – bombs and doodle-bugs; spiders and thunderstorms; attacks by lurking strangers. Mum insisted that we walk down the middle of the road if we were walking down to Granny and Grandad's after dark – an impenetrable dark due to the blackout – no lights were allowed anywhere. She warned us that someone might jump out at us if we walked close by the hedges! And after the War, if there was a thunderstorm during the night, she'd wake us and take us downstairs to sleep under the table.

At the end of the War Mum rented a house at 117 Athelstan Road, two doors down from Granny and Grandad at 121. One day, she told us that Dad was coming home, he had been ‘demobbed’ – what did that mean? I scarcely remembered what my father looked like as he'd been in the Army during the war, rarely coming home on leave, although we did have a photo of him (above) in his uniform. Dolly and I were playing outside one day after school, our bikes leaning up against the wall, when a man appeared, walking down the road – a man I didn't recognise, although Dolly, being two years older than me, did, and ran to meet him. I hardly knew what the word ‘Dad’ meant. And yet I still can picture a smiling, curly-haired man in a navy suit that was just a little too tight for him – the ‘demob’ suit that all returning soldiers were issued with. I still have his ‘demob’ suitcase, a wooden one with a simple but very secure metal fastening. A couple of faded green labels are still stuck on it, one ‘British Railways Local’ and the other ‘4d paid.’ It sits in my study and is full of Dolly's compositions and arrangements, holding about a tenth of her work.

It took a while for all of us to get used to being together again, and the joy of having Dad safely home didn't last. Mum had a job as a bus conductress. She'd worked on the trams in Hastings towards the end of the war, and had battled to be paid a man's wages. She now seemed to fight everybody. Dad wanted her to stop work, he wanted to be head of the household again, but Mum refused; she was used to earning her own living and she wasn't going to give that up. So the love that these two people had once felt for each other was now replaced by loathing. Here's one love-song to her from Dad's wartime book of poems.

She is to me a gem of beauty, never was one so fair

The sunlight fades to nothingness in the gleam of her golden hair

The stars of heaven their utmost try to dim her radiant eyes

Her smile so gay, like dancing beams mirrored from April skies

And who could help but fall in love with her whom my heart seeks

The softest winds of eventide just stay to kiss her cheeks

And murmuring on, swell to a hymn to praise her wondrous grace

Their reunion wasn't the happy one told of in so many folk songs, lovers re-united despite the great odds of a soldier returning safe home after serving abroad for seven long years ‘fighting for strangers’.

And here is the ring that between us was broken

In the depths of all danger, love to remind me of you

And when she saw the token she fell into his arms

Saying ‘You're welcome lovely William from the Plains of Waterloo’1

By now Mum was scornful of Dad for what he had become – a mildly conservative man, joining the Ratepayers’ Association (perhaps to annoy, or spite Mum), and also because he was a Football Pools agent, something she didn't approve of. I can still feel the paralysing misery of meals together in the kitchen, the tension: Dolly and me sitting on the wooden bench on one side of the scrubbed pine table, not daring to move, Mum and Dad on the other. Mum would bang the dishes and plates down hard on the table – a habit she retained all her life – then throughout the meal complain that she couldn't put up with the way Dad ate, gobbling up his food she'd say, being a noisy eater; then him retaliating by pushing his plate away and leaving the table – and the house – before he'd finished his meal.

Dolly and I were caught between the two of them, and often sought refuge at Gran and Grandad's, needing to be with grown-ups who loved each other as well as us. We knew that something horrible was happening, but we didn't understand why. Granny told me how fond they had become of Dad over the years, although initially they had taken against him because his grandparents were Irish and lived outside Ore village in Red Lake. The match wasn't approved of, as Red Lake was considered to be a bit of a rough district. But Dad was a pleasant, intelligent, straightforward man, handsome, too, with thick, curly dark hair. Mum had fair, wavy hair. (Dolly got Dad's colour but Mum's wave, while I got Mum's colour with Dad's curls.) And when I see photos of a young Dolly I think of the lines in the song ‘Rolling in the Dew’: ‘with her red rosy cheeks and her coal-black hair.’

Naturally Dolly and I had grown to love our father again and we were just happy to have him at home. He took a job with a laundry firm, delivering to customers out in the country – the rural route. He'd take us out sometimes in his delivery van. He was a genial man, and his customers liked him, giving him presents of eggs, rabbits and teenagers’ magazines for Dolly and me. When he took us ‘down town’ or to the seafront, he'd buy us ice-cream wafers instead of cornets (they weren't called ‘cones’ then), and that felt much more grown-up. He'd take us into amusement arcades on the pier to play on the penny slot machines, an activity of which Mum really disapproved. But surely it was harmless fun in those days and to me, thoroughly enjoyable, as you could – though rarely – win prizes of sweets, or sometimes a little packet of cigarettes, though both would have been too stale to either eat or smoke. Even more exciting were the times he took us to speedway racing at the Pilot Field to watch Split Waterman, so dashingly clad in his black leathers; how handsome he was with his dark hair and elegant moustache, thrilling us as he screeched at speed round the bends, his bike almost horizontal to the track, one booted foot dragging on the ground. The noise was so exciting and the air was charged with the smell of a unique combination of hot fuel and the burning cinders of the track.

Before too long, though, the situation between Mum and Dad became intolerable. He left home and moved in with a red-haired widow and her two children who lived close by. Dolly and I would see them out as a family together, leaving us not only bewildered and bereft, but having to live with an embittered mother, now faced once again with bringing up two children on her own. Not only were Dolly and I sad, we felt ashamed, too. I thought this was only happening to us, but I'm sure it must have been repeated in many families although it was never spoken about, not with Mum or Gran, nor our friends at school.

Then Dad moved away from Hastings, and settled in Shirley, a district of Southampton. How could a place be named Shirley? Was it done to spite me? And I remember a story my mother had told me – quite recently – that when I was born, my parents hadn't thought of a name for me. And while they were at Granny and Grandad's one day, showing them the new baby, Dad looked out of the window, and noticed the bungalow opposite was named Shirley. Problem solved! At least, I thought, Mum could have pretended I was named after the Charlotte Brontë novel.

I only saw my father once more in my life; he turned up at a concert Dolly and I were giving in Southampton when we were in our thirties. He had brought us a quarter pound box of Milk Tray chocolates each, and spoke to us almost as if we were still the school children he had abandoned – or been driven away from.

So what do I remember of my Dad? His hazel eyes, his tanned arms on the steering wheel as he drove his van and his own father's name, Leonard Collins, on the World War I memorial outside the church in Ore Village.