Gyalwa Gendun Gyatso wrote a verse work on the theme known in Tibetan as ta-cho-gom, or “view, activity and meditation.” The text reveals his direct and quintessential approach to spiritual issues. “View” refers to the reality of emptiness of all things, the great void nature that is the highest essence;

“activity” refers to the manner in which we experience the world; and “meditation” refers to the yoga that integrates spiritual methods and ideas with our ordinary life.

The colophon to the text states that Gendun Gyatso penned it while living in meditation retreat in the Olkha Mountains. As no date is mentioned in regard to it, and as he made pilgrimage to these sacred hills almost annually throughout his adult life, there is no way to establish a time line. However, it does reveal considerable maturity, so we can presume that it was written during his later years.

To the feet of my holy teacher constantly I bow down;

And I bow to the feet of the great master Lama Tsongkhapa,

A thought of whom destroys the terrors of samsara

And in a single moment bestows all needs, ultimate and mundane.

The view which understands things as they really are, the deepest mode of being,

Is a meditative experience divorced from mental dullness and agitation.

In action it perfectly unites wisdom with method And it spontaneously produces the fruit of buddhahood’s three perfect bodies.

As for the object of the view,

It is not made artificial by conditions; in essence it is unchanging.

By nature it is pure, it is beyond concepts of good and evil.

It is all-pervading, the ultimate nature of everything And is the quintessence of the essence;

And, understanding it, one passes beyond the bounds of entanglement.

This world we see is a painting

Born from the brush of discursive thought,

And within or upon it nothing truly existent can be found.

All things in samsara and nirvana are but mental labels and projections.

Knowing this one knows reality; seeing this one sees most true.

Understand clearly the natures of both

The limitless diversity and the one-tasteness of things,

And make this understanding firm as the very King of Mountains.

This is the key that opens the door of a hundred samadhis.

Meditative focus which abides firmly and without motion,

And insight which reasons precisely to the underlying nature of all things:

By combining these, the seeds of the two Obscurations are forever abandoned.

He who does just that is known as a great meditator.

In essence, from the very beginning

No difference can be found between samsara and nirvana;

Yet good and evil actions invariably produce according results.

The Great Way in action is the practice of the six perfections On the basis of this understanding.

The inseparability of emptiness and the manifest Is the basis of the view;

The path to be practiced is the twofold collections of goodness and wisdom;

The result is the spontaneous birth of buddhahood’s two kayas. These are the view, meditation, action and attainment Most pleasing to the Enlightened Ones.

This selection from the Second Dalai Lama’s many writings is an essay he wrote on the meditative lineage brought to Tibet from Indonesia by Atisha, and popularized by the Kadampa School under the name lojong, or “mind training.” This tradition speaks of the path to enlightenment as comprising two principal applications: the cultivation of the aspiration to buddhahood based on universal love and compassion; and, secondly, the cultivation of the wisdom of emptiness. It calls these two jangsem nam nyi, or “the two enlightenment minds.” I follow the lead of the late Mongolian master Geshey Wangyal in translating the Tibetan term jangchub kyi sem as “bodhimind.

The colophon to the essay simply states, “Written by the Buddhist teacher Gyalwa Gendun Gyatso at the request of the female practitioner Kunga Wangmo.” This was one of the Second’s many female disciples.

Homage to the lotus feet of Atisha

Who is inseparably one with incomparable Tsongkhapa.

Herein I set forth a simple string of words Briefly explaining how to meditate Upon the two types of bodhimind—

Conventional and ultimate—

The essence of their teachings.

Meditation upon the conventional bodhimind—the aspiration to attain buddhahood oneself as the best means to benefit all sentient beings— begins with meditation upon love and compassion. This forms the basis of the meditation known as “giving and taking,” the principal technique used [in the Atisha/Tsongkhapa tradition] for arousing the conventional bodhimind.

Sit upon your meditation seat in a comfortable posture and visualize your mother of this life sitting before you. Contemplate how she carried you in her womb for almost ten months, and how during this time she experienced much suffering and inconvenience for you. At your actual birth her pain was as intense as that of being crushed to death, yet she did not mind undergoing all this misery for you, no matter how great it was. And, when you finally emerged from her womb, looking like a naked and helpless worm covered in blood and mucus, she took you lovingly in her arms and placed you to her soft flesh to give you warmth; gave you milk from her own breast, prepared food for you, cleaned the mucus from your nose and the excrement from your body, looked with a smiling coun-tenence upon you and at night sacrificed her own comfort and sleep for you. Throughout your childhood she would rather become ill herself than permit you to become ill, and would even rather die than permit harm to come to you. As you grew up, the things that she treasured too dearly to use herself or to give to others she gave to you: the best of her food she gave to you, as well as clothing, both warm and soft. She was willing to do anything for you, even at public disgrace to herself. Ignoring her own happiness in this life and the causes of her happiness for future lives [i.e., good karma], she thought only of how to provide for your comfort, happiness and well-being. But her kindness did not end even there. That you have met with the spiritual guides and now have the opportunity to study and practice the holy Dharma—and thus to accomplish peace and happiness for this life and beyond—are purely a result of her kindness.

Meditate in this way until you appreciate her more than anything else, until your heart opens to her with love, and the mere thought of her brings joy to your mind.

Then contemplate how this mother of yours has the burden of the sufferings of birth, old age, sickness and death placed upon her body and mind, and that when she dies she must wander helplessly into the hereafter, perhaps even to the lower realms of existence [hell, hungry ghost or animal worlds].

If you meditate in this way long enough and with sufficient concentration you will spontaneously give birth to a sense of compassion toward her as great as that felt by parents who witness their only child being tortured in a pit of fire.

You should then think, “If I do not accept responsibility to produce the beneficial and to eradicate the harmful for my own mother, who will accept it? If I do not do something, who will?”

But exactly what harms her? Suffering and negativity. Moreover, suffering is the immediate cause of harming her, whereas negativity is the indirect cause. Think: “Therefore it is these from which I should separate her.”

Contemplate thus; and as you breathe in, visualize that together with your breath you are inhaling all her present sufferings and unsatisfactory conditions as well as the negative karma and distorted mental conditions [attachment, aversion, etc.] that are the causes of all her future suffering. These peel away from her body and mind and come to your heart in the form of a black cloud drawn in by your breath. Generate conviction that she is thereby set free from suffering and its causes.

Similarly, exactly what benefits her? Happiness and goodness [i.e., positive karma]. Moreover, happiness immediately benefits her whereas goodness indirectly does so. Think: “Therefore, it is these that I should give to her.”

Meditate thus, and as you breathe out, visualize that together with your breath you are exhaling a white cloud of happiness and goodness/ This enters into her heart and satiates her with a wondrous mass of happiness, virtue and goodness, and causes her to progress toward buddhahood.

Then, just as was done above by using your mother as the object of meditation, consider how all friends and relatives, having been your mother again and again in previous lives, have shown you the same kindness as has your present mother. In a previous life, they, as your mother of that life, have shown you all the kindness of a mother. In that respect they are every bit as deserving of your love and appreciation as is the mother of this life. Contemplate over and over how they were kind mothers, until the mere sight of any of them fills your heart with joy and appreciation.

Then consider how, enmeshed in suffering, they are barren of true happiness. Continue meditating in this way until compassion, unable to bear their pitiable state, arises.

When both love and compassion have been generated, engage the meditation technique called “giving and taking” as previously explained.

When this has been accomplished, visualize before you three people: a person whom you dislike, a friend, and a stranger [i.e., someone toward whom you have no emotion]. Although their memories may be clouded by the continued experiences of death, the intermediate state [between death and rebirth] and rebirth, in actual fact each of them has been your mother in countless previous lives. On those occasions each of them has shown you the same kindnesses as has your mother of this life, benefiting you in limitless ways and protecting you against whatever threatened your well-being. Generate love and compassion for them as before, and then use them as the object of meditation in “giving and taking.”

Next meditate upon how all beings of the six realms have repeatedly been your mother in lifetime upon lifetime. Engender love and compassion toward them, and engage the practice of “giving and taking.” Through inhalation take away all their sufferings—the heat of the hot hells; the cold of the cold hells; the starvation of the hungry ghosts; the merciless brutality and so forth of the animal world; the sufferings of birth, sickness and old age, etc., of mankind; the violence of the antigods; the misery of death and migration of the lower gods; and the subtle, allembracing suffering of the higher gods. Then through exhalation,

meditate on giving them all that could make them happy: well-cooled breezes to the hot hells; warmth to the cold; food to the hungry ghosts; etc.

Finally, visualize any enemies or people who have harmed you. Contemplate how, obscured by ignorance and by the effects of repeated birth, death and transmigration, they do not recognize that they have many times been your mother, and you theirs; but, overpowered by karmic forces and by mental obscurations, they are blindly impelled to cause you harm in this life. However, if your kind mother of this life were suddenly to go crazy, verbally abuse you, and attack you physically, only if you were completely mindless would you react with anything but compassion. In the same way, the only correct response to those who harm or abuse you in this life is compassion.

Meditate like this until love and compassion arise, and then meditate upon “giving and taking”—taking the immediate and indirect causes of their anger, distortion and unhappiness, and giving them the causes of peace and joy.

In brief, with the exception of the buddhas and one’s personal gurus one should meditate upon “giving and taking” with all beings, even tenth-level bodhisattvas, shravaka arhats and pratyekabuddhas, who have the faults of subtle stains of distorted and limited perception still to be abandoned. There is no purpose, however, in visualizing “giving and taking” with the buddhas, for they, having exhausted all their faults, have no shortcomings to be removed or qualities to be attained. As for one’s personal teachers, it is improper to use the meditation of “giving and taking” with them as the object because it is incorrect for a disciple to admit a fault in his/her teachers. Even if one of one’s teachers seems actually to have faults, the disciple should not visualize removing them. To the buddhas and one’s teachers one can only make offerings of one’s goodness and joy.

At this point in the meditation you should ask yourself, “However, do I really have the ability completely to fulfill the needs of all living beings?

Answer: Not only does an ordinary being not have this ability, even a bodhisattva of the tenth level does not.

Question: Then who does?

Answer: Only a fully and perfectly enlightened being: a buddha.

Contemplate this deeply, until you gain an unfeigned experience of the aspiration to attain the state of complete buddhahood as the supreme method of benefiting all living beings.

Sometimes the thought of “I” suddenly arises with great force. If, at these moments, we look closely at how it appears, we will be able to understand that although from the beginning this manifest “I” seems to be inherently existent within the collection of body and mind, in fact it does not exist at all in the manner in which it seems to exist because it is a mere mental imputation.

The situation is like that of a rock or tree seen protruding from the peak of a hill on the horizon. From a distance it may be mistaken for a human being, yet the existence of a human in that rock or tree is only an illusion. On deeper investigation, no human being can be found in any of the individual pieces of the protruding entity, nor in its collection of parts, nor in any other aspect of it. Nothing in the protrusion can be said to be a valid basis for the name “human being.”

Likewise, the solid “I” which seems to exist somewhere within the body and mind is merely an imputation. The body and mind are no more represented by the sense of “I” than is the protruding rock represented by the word “human.”

This “I” cannot be located anywhere within any individual piece of the body and mind, nor is it found within the body and mind as a collection, nor is there a place outside of these that could be considered to be a substantial basis of the object referred to by the name “I.”

Meditate in this way until it becomes apparent that the “I” does not exist in the manner it would seem.

Similarly, all phenomena within cyclic existence and beyond are merely imputations of “this” and “that” name, mentally projected upon their basis of ascription. Other than this mode of existence they have no established being whatsoever.

Meditate prolongedly upon this concept of emptiness. Then in the post-meditation periods maintain an awareness of how oneself, samsara and nirvana are like an illusion and a dream. Although they appear to the mind, they are empty of inherent existence.

Because of this non-inherent nature of things, it is possible for creative and destructive activities to produce their according karmic results of happiness and sorrow. They who gain this understanding become sages abiding in knowledge of the inseparable nature, the common ground, of emptiness and interdependent origination.

This then is an easily understood explanation Of the glorious practices of higher being That plant the imprint of the two Buddhakayas.

I urge you to practice it,

The pure essence of the Great Way.

To close this chapter, I am including a brief verse work by the Second Dalai Lama that he wrote on tantric practice.

Although all Dalai Lamas have followed and taught a union of the sutra and tantra teachings of the Buddha, the Second, Fifth and Seventh wrote most extensively on the tantric way. The Second’s commentaries to the Six Yogas of Naropa and also the Six Yogas of Niguma, two tantric systems popular with all sects of Tibetan Buddhism, are famed for their directness and clarity, and have retained their popularity over the centuries. He also wrote extensively on lesser known tantric systems, such as the lineages of the Zhichey and Zhicho traditions.

In the following text he summarizes the essence of tantric application. A commentary to it could run into hundreds of pages and still not exhaust all its implications.

The guru is the source of all tantric power;

The practitioner who sees him as a Buddha Holds all realizations in the palm of his hand.

So devote yourself with full intensity To the guru in both thought and deed.

When the mind is not first well trained In the three levels of the exoteric path,

Then any claim to the profound tantric yogas Is an empty boast, and there is every danger That one will fall from the way.

The door entering into the peerless Vajrayana Is nothing other than the four tantric initiations.

Hence it is important to receive these fully And thus plant the seeds of the four Buddhakayas.

One must learn to relinquish the habit of grasping At the mundane way in which things are perceived,

And to place all that appears within the vision Of the world as mandala and its beings tantric forms.

Such are the trainings of the generation stage yogas,

That purify and refine the bases to be cleansed.

Next one stimulates the points of the vajra body And directs the energies flowing in the side channels Into dhuti, mystic channel at the center,

Thus gaining sight of the clear light of mind And giving rise to wisdom born together with bliss.

Cherish meditation on these completion stage yogas.

The actual body of the final path to liberation Is cultivation of the perfect view of emptiness;

The gate entering into illumination’s Great Way Is the bodhimind, the enlightenment aspiration;

And the highest method for accomplishing buddhahood Is meditation on the two profound tantric stages.

Hold as inseparable these three aspects of practice.

This poem summarizing the key points of tantra Is here composed by the monk Gendun Gyatso For his disciple Chomdzey Sengey Gyatso

While residing at Drepung, a great center of Dharma knowledge.

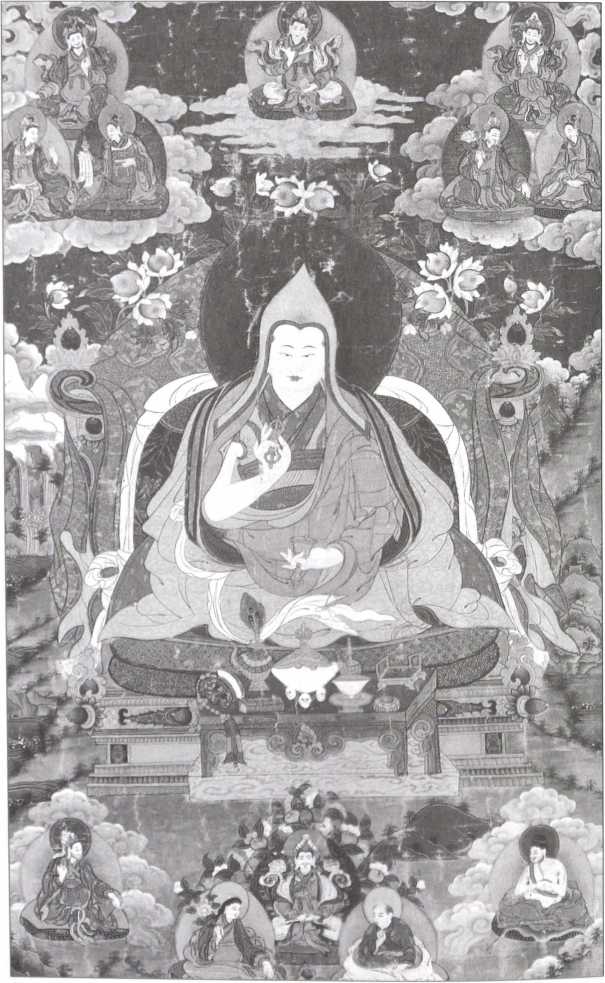

Sonam Gyatso, the Third Dalai Lama. Photo from Neg. No. 336307, 70.2-87-2. Gourtesy of the Department of Library Services, American Museum of Natural History, New York.