the devil always shits in the same place

Why work, or even gamble for that matter, when there are fareasier ways of enriching yourself?

lipoushka (Russian) a stick with a gluey end for stealing money from a counter (literally, flypaper)

butron (Spanish) a type of jacket with inner pockets worn by shoplifters

levare le scarpe (Italian) to steal the tyres from a car (literally, to take someone else’s shoes off)

rounstow (Scots) to cut off the ears of a sheep, and soobliterate its distinctive marks of ownership

bait (Arabic) incentive or motive

egg (Norwegian, Swedish) knife edge

gulp (Afrikaans) to slit, gush, spout

guru (Japanese) a partner in crime

plaster (Hebrew) deceitful or fraudulent

roof (Dutch) robbery

Although once you step over that line, who knows what company you may be forced to keep:

ladenlichter (Dutch) a till-robber

pisau cukur (Malay) a female hustler who cons men into giving her money

harza-duzd (Persian) someone who steals something of no use to him or anyone else

adukalipewo (Mandinka, West Africa) a highway robber (literally, give me the purse)

belochnik (Russian) a thief specializing in stealing linen off clothes lines (this was very lucrative in the early 1980s)

Considerable skill, experience and bravado may be required for success:

forbice (Italian) pickpocketing by putting the index and middle fingers into the victim’s pocket (literally, scissors)

cepat tangan (Malay) quick with the hands (in pickpocketing or shoplifting or hitting someone)

poniwata (Korean) a victim who at first glance looks provincial and not worth robbing, but on closer scrutiny shows definite signs of hidden wealth

komissar (Russian) a robber who impersonates a police officer

And sometimes even magic:

walala (Luvale, Zambia) a thieves’ fetish which is supposed to keep people asleep while the thief steals

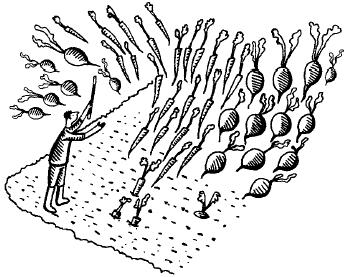

za-koosirik (Buli, Ghana) a person who transfers the plants of a neighbour’s field to his own by magic

In their eagerness to move into and conquer new markets, many huge Western companies forgot to do their homework. When the name Microsoft was first translated into Chinese, they went for a literal translation of the two parts of the name which, unfortunately, meant ‘small and flaccid’.

Pepsi’s famous slogan ‘Come Alive with Pepsi’ was dropped in China after it was translated as ‘Pepsi brings your ancestors back from the grave’.

When American Airlines wanted to advertise its new leather first-class seats in the Mexican market, it translated its ‘Fly in Leather’ campaign literally, but vuela en cuero meant ‘Fly Naked’ in Spanish.

Colgate introduced in France a toothpaste called Cue, the name of a notorious pornographic magazine.

Coca-Cola was horrified to discover that its name was first read by the Chinese as kekoukela, meaning either ‘bite the wax tadpole’ or ‘female horse stuffed with wax’, depending on the dialect. Coke then researched 40,000 characters to find a phonetic equivalent – kokou kole – which translates as ‘happiness in the mouth’

Their trains and tubes are punctual to the nearest second; equal efficiency seems to characterize those Japanese who take criminal advantage of such crowded environments:

nakanuku, inside pull-out: to carefully slip one’s hand into a victim’s trouser pocket, draw out the wallet, flick it open, whip out cash and credit cards, close it and slip it back into the victim’s trouser pocket

oitore, walking next to a well-dressed victim, plunging a razor-sharp instrument into his attachÉ case and cutting the side open

okinagashi, put and flow: those who climb on a local train at one station, grab bags and coats, cameras and camcorders, and then jump off at the following station

takudasu, kindle and pull out: to drop, as if by mistake, a lit cigarette into a victim’s jacket or open shirt, and then, while the victim is frantically trying to locate the burning butt, come to his aid, helping him unbutton and frisk through jacket, shirt and undershirt, taking the opportunity to lift wallets and other valuables out of pockets and bags

Nor does this fine vocabulary dry up when describing the activity of Japanese burglars: maemakuri, lifting the skirt from the front, means they enter through the front gates; while shirimakuri, lifting the skirt from behind, describes entry through a gate or fence at the rear of the house. One obvious hazard is the gabinta, the dog, that starts barking or snarling at the intruders (the word literally means ‘this animal has no respect for its superiors’). There is only one way to deal with such an obstacle: inukoro o abuseru, the deadly pork chop, otherwise known as shūtome o kudoku, silencing one’s mother-in-law. Once at the door you confront the mimochi musume, the lock (literally, the pregnant daughter), who must be handled with the softest of touches, unless of course you are in possession of the nezumi, the mice (or master keys).

As for the crooks themselves, they come in all varieties. There is the sagarigumo, or descending spider, the man or woman who braves the slippery tiles of the roof to reach their target; the denshinkasegi, the telegram breadwinners, who get there by shinning up telephone poles; the shinobikomi, thieves who enter crawling; the odorikomi, who enter ‘dancing’, i.e. brash criminals with guns; the mae, or fronts, debonair thieves who simply walk up to the main door; or the super-sly ninkātā, who leaves no trace: the master thief.

There is the ichimaimono, the thief who works alone; and the hikiai, those who pull together, i.e. partners in crime. There are nitchūshi, broad-daylight specialists, and yonashi, night specialists; even miyashi, shrine specialists. There are akisunerai, empty-nest targeters, those who specialize in targeting unattended houses; neshi, sleep specialists, the men who target bedrooms after the loot has been assembled and packed; and even evil tsukeme, literally, touching eyes: thieves who barge into bedrooms to rape sleeping victims.

Not content with colourful descriptions of robbers, the Japanese have an extensive vocabulary for cops too: there are the gokiburi, the cockroaches, policemen on motorcycles, who can follow burglars over pavements and through parks; the kazaguruma, the windmill, an officer who circles the streets and alleys, getting closer and closer to the area where the criminals are working; the daikon megane, the radish with glasses, the naive young officer who’s not going to be a problem for the experienced crook; or the more prob-lematic oji, the uncle, the dangerous middle-aged patrolman who knows all the members of the gang by name and is liable to blow the whistle first and ask questions later.

As if that wasn’t enough, policemen on those overcrowded islands can also be described as aobuta (blue pigs), en (monkeys), etekō (apes), karasu (crows), aokarasu (blue crows), itachi (weasels), ahiru (ducks), hayabusa (falcons), ahōdori (idiotic birds, or albatrosses), kē (dogs), barori (Korean for pig), and koyani (cat, from the Korean koyangi). Officers even turn into insects such as hachi (bees), dani (ticks), kumo (spiders), mushi (bugs) and kejirami (pubic lice).

‘Punishment,’ say the Spanish, ‘is a cripple, but it arrives.’ Criminals may get away with it for a while, but in the end justice of some kind generally catches up with them:

chacha (Korean) the disastrous act of each gang member dashing down a different alley

afersata (Amharic, Ethiopia) the custom, when a crime is committed, of rounding up all local inhabitants in an enclosure until the guilty person is revealed

andare a picco (Italian) to sink (to be wanted by the police)

cizyatiko (Mambwe, Zambia) to make a man believe that he is safe so as to make time for others to arrest him

panier à salade (French) a salad shaker (a police van)

annussāveti (Pali, India) to proclaim aloud the guilt of a criminal

All except the perpetrator are happy to see that anyone taking the immoral shortcut to personal enrichment ends up in a very bad place:

obez’ yannik (Russian) a detention ward in a police station (literally, monkey house)

butabako (Japanese) the cooler, clink (literally, pig box)

bufala (Italian) a meat ration distributed in jail (literally, she-buffalo – so called because of its toughness)

And society may exact its just deserts:

gbaa ose (Igbo, Nigeria) to rub in pepper by way of punishment or torture

kitti (Tamil) a kind of torture in which the hands, ears or noses of culprits are pressed between two sticks

dhautī (Sanskrit) a kind of penance (consisting of washing a strip of white cloth, swallowing it and then drawing it out of the mouth)

ráhu-mukhaya (Sinhala, Sri Lanka) a punishment inflicted on criminals in which the tongue is forced out and wrapped in cloth soaked in oil and set on fire

barathrum (Ancient Greek) a deep pit into which condemned criminals were thrown to die

tu-tù (Vietnamese) a prisoner ready for the electric chair

vodoi nye pozolyosh (Russian) water can’t be separated

aralarindan su sizmaz (Turkish) not even water can pass between them

entendre comme cul et chemise (French) to get along like one’s buttocks and shirt

uni comme les doigts de la main (French) tied like the fingers of a hand

una y carne ser como (Spanish)/como una y mugre (Mexican Spanish) to be fingernail and flesh/like a fingernail and its dirt