THE SCREAMING EAGLES

Hearts and Minds: An Author’s Note

On an early October morning, I climbed into a waiting Black Hawk helicopter for the two-and-a-half-hour flight from Baghdad to Mosul. I was with my long-time Green Beret friend and Iraq traveling companion, Russell Cummings, on our way to the headquarters of COL Joe Anderson and his “Screaming Eagles,” the 101st Airborne.

The Baghdad outskirts flashed below me, miles and miles of crops and date palms growing in the Euphrates and Tigris fertile valley, helped along by a huge irrigation program. An hour out of Baghdad, we passed over Tikrit. Below us, we could see the palaces in the city of Saddam Hussein’s youth.

Huge rocks and endless sand covered the ground below—a veritable no-man’s-land of desolation. I thought of the Green Berets of the 10th Special Forces Group (Airborne) who, a few months earlier, had landed in Bashir. They must have been discouraged at best, with their shot-up airplanes flying over such desolate territory.

I was certainly happy to be in a functional Black Hawk as we approached our landing at the helipad, owned presently by the 101st Airborne Division. You had to be a tiger in the air to survive this area, surrounded as it was by such inhospitable wasteland. Yet, as we settled into the helipad, I could see the grand palaces that defied the hardscrabble city surrounding them.

We landed in Mosul and were met by a delegation from the Strike Brigade and “Strike Six,” COL Joe Anderson. We were quickly whisked away with our impedimenta, and taken to the HQ of the 101st Airborne Division, a palace complex that had been looted by the Iraqis, and then made functional again by the 101st. Our first stop was the palace that had been acquired by the officers in charge of the Air Force contingent.

The usual group of Public Affairs Officers (PAOs) greeted us. They had managed to set up their offices in the finest areas of the most luxurious palace available. We were introduced to the various commanders of the Mosul units, after which we were taken by MG (Major General) David Petraeus to a briefing on the Screaming Eagles and their activities as they tried to create order from a greatly disordered city. I’m afraid that I, having Parkinson’s and the dry irritable eyes that accompany this affliction, had to close my eyes for a few minutes of the briefing. I assure the reader (and the general) that I not only absorbed every word of the briefing, but made sure to include them in the following pages.

After his presentation, we took our leave of the general, and walked to the HQ palace where COL Joe Anderson was waiting for us. I immediately felt a kinship with the colonel. We discussed some of his group’s exploits over the past three months since the Screaming Eagles had invaded Iraq from Kuwait via the outskirts of Basra.

The most recent newsworthy event of the war at that time was claimed by Anderson’s brigade, when only months before, they had located and dispatched the two sons and a grandson of Saddam Hussein in Mosul.

Before the briefing, CSM (Captain Sergeant Major) Jerry Lee Wilson introduced himself to me. He was obviously close friends with the colonel; much more so than the ordinary bond of an NCO and his commander.

In the course of getting to know each other, COL Anderson showed me some photographs of himself and his activities since his arrival in Mosul. There were videotapes taken from the inside of the cars and humvees that they drove around in.

“Weren’t you afraid of getting shot at by the pro-Saddam Iraqis and their Al Qaeda friends?” I asked.

“No,” the command sergeant major answered. “We kept our eyes open and were prepared to shoot our way out if we had to.”

It didn’t surprise me that the troops weren’t particularly worried about the terrorists in the area. I noticed that almost every soldier I met in Iraq wore a black bulletproof vest in addition to their camouflage flak jackets, and they usually carried an M16A2 assault rifle, frequently with a 40mm M203 barrel mounted underneath for firing grenades. I, too, had taken to wearing the black bulletproof vest as a matter of course, although civilians were not allowed to carry machine guns. My particular vest had been loaned to me by my friend COL Bob Morris; it was the same one he wore when traveling in foreign countries where the population was suspect.

I spent the rest of the afternoon and evening talking to “Smokin’ Joe” Anderson, as he was known by his friends. Listening to his war experiences, fighting his way up from Basra to Mosul for four weeks, I was completely fascinated with the baldheaded colonel. We both decided that if a movie were made of the war, the perfect actor to play the part of him would be Yul Brynner. Unfortunately, Brynner had died in 1985 from cancer, caused by smoking.

I had hoped that perhaps “Smokin’ Joe” would invite Russell and me to go out with him on his nightly foray looking for the bad guys. He said he had just received some information about two terrorists and their Iraqi friend who were in the area and were going to be causing trouble that night.

However, COL Anderson did not ask me to go with him on this trip for the obvious reason that I was carrying a cane, and my Parkinson’s could have thrown me off balance, thereby endangering the whole operation. Looking at it from Joe’s point of view, I could see why he would not want a seventy-eight-year-old parkinsonian to be sitting in a humvee with him if he got into a firefight with a few pro-Saddam insurgents or the Al Qaeda. We were later informed that at about 0400 hours, Anderson and his soldiers had indeed found, engaged, and shot the Al Qaeda and Hussein loyalists.

After I had returned to the United States, it was with great sadness that I picked up a newspaper and learned that CSM Jerry Lee Wilson had been assassinated by a group of terrorists who cornered his jeep and sprayed him with AK-47 fire. The newspapers said that the bodies had been dragged from their vehicle and desecrated by anti-American Iraqis.

When I asked Joe about this by e-mail, he assured me that was not the true story. The attack had taken place unexpectedly and the terrorists who had fired the shots had killed him but then had immediately disappeared. To this day, I do not know the whole truth of the matter. It has brought to light the great effort of the military to suggest to the American public, through the press, that the soldiers in Iraq were winning the hearts and minds of the people there. More importantly, they tried to show that the local residents did not appreciate the work of a few terrorists. This entire “hearts and minds” subject, which I had dealt with in Vietnam on two visits, was something everybody talked about, but had not really seen too often—just as the terrorists had emerged from nowhere to kill Jerry Lee, the Viet Cong had struck and disappeared back into the indigenous population in Vietnam. Many of us in Vietnam and in other terrorist areas agree that “if you get them by the balls, their hearts and minds will surely follow.”

The Associated Press (AP), FOX News, Reuters, and other news agencies had reporters embedded with troops at many of the sites, and even with the Special Forces. War is won with information as well as fighting, and the war could not be won if the Iraqi people and the rest of the world, particularly the Arab world, could not see the “ground truth” firsthand.

In October 2003, at the Sheraton in Baghdad, I met Dana Lewis, who had been in Iraq previously, reporting for NBC TV, and later, for FOX News. Dana had been an embedded reporter with the 101st Airborne, from before the time they crossed the Kuwaiti border until they had entered Baghdad. Dana was great friends with COL Anderson, and told me much about the Strike Brigade and his journey with them into Iraq. We exchanged contact information, and kept in touch after I returned to the States. Dana has kept me abreast of the continuing situation in Iraq, and is still there as of the date of this book’s publication.

Back Stateside, I asked for Dana’s view of the story—the war as seen through his eyes. Part of what follows in the next section is Dana Lewis’s “War Diary,” which documented his experience and tells the stories of the Screaming Eagles in Iraq better than anyone else could hope to. Dana rolled all the way into Baghdad with the 101st, witnessing the events from the military side, but through civilian eyes. Here is his story, re-created from the pages of his daily journal and written interviews.

The Beginning

[DANA LEWIS]

We had just finished a week of chemical/biological training, and another week of battlefield survival skills. The instructors had gone so far as to suggest Iraq may be too dangerous, but somehow it really didn’t register with me. I had covered wars in Afghanistan, Kosovo, and the Middle East. It didn’t register until my producer delivered my Army-style dog tags.

“Dana Lewis; NBC; blood type and allergy to penicillin.”

The thing was—there were two of those tags to wear around my neck.

“Why two?” I had asked.

“Well, one stays with your body, and the other is for Army records if you die,” she said.

I never went to Iraq to die.

I had promised my wife and family that I was a survivor, and would come home. But everyone knew the risks were real; the chances of getting wounded were extremely high. What I know is that every dangerous assignment always seems worse when you’re thinking about going. I kept telling myself, “Once you’re on the ground, Dana, you feel your way, you feel your feet on the ground and it’s not so scary or difficult.”

I thought this time I was kidding myself. It was scarier and more difficult than anything I had ever done.

The Screaming Eagles

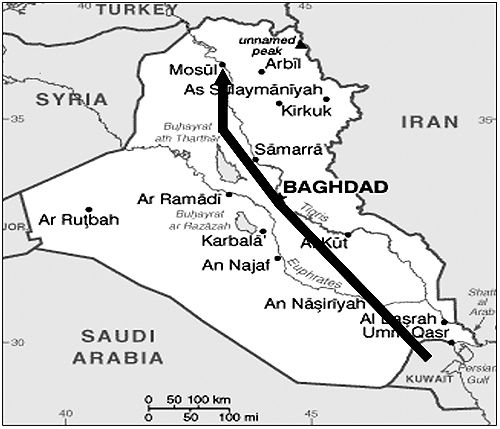

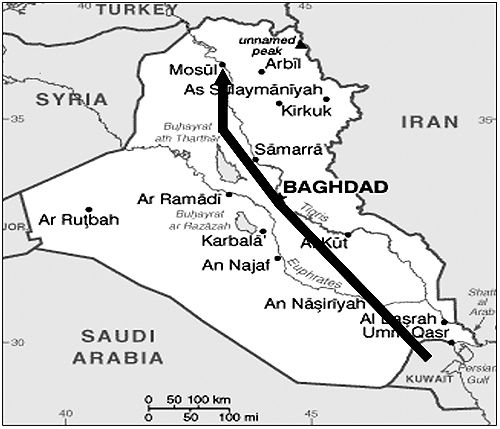

The 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) was commanded by MG David Petraeus. Known as “the Screaming Eagles,” they performed two of the longest air assault missions in history as they fought their way up the gut of Iraq during Operation DESERT EAGLE II, making their way through Baghdad, and ending up in the city of Mosul, where they took over the northern city from Task Force VIKING’s Green Berets. Courtesy: CIA World Factbook 2003

Kuwait

COL Joe Anderson is the commander of Strike Brigade, the second of three brigades of the Screaming Eagles, 101st Airborne, based out of Fort Campbell, Kentucky. He’s known to those around him as “Smokin’ Joe.” When asked, Joe explained to me, “That [moniker] started as a boxer at West Point and continued as a LT and CPT because of my fitness, aggressiveness, and personality. As a Ranger Company Commander, I led the Joint Special Operations Task Force main effort in [Operation] JUST CAUSE (B Co, 2-75 Ranger Regiment). [Operation JUST CAUSE was the invasion of Panama, which deposed Manuel Noriega in December 1989.]

“We combat airborne assaulted onto Rio Hato to fight the Macho de Monte Company (Panamanian Rangers) and a motorized company. Both of these companies were loyal to Noriega and responded to the coup in the fall of ’89—that is why they were the main objective for the invasion. We then moved downtown to secure the U.S. Embassy and then took control of the town and area of Alcalde Diaz. I was one of six Bronze Star recipients for the 2nd Ranger Battalion—those medals weren’t given out like they were for DESERT STORM or OEF/OIF.”

Joe is a friend. I first met him in Kosovo when U.S. forces rolled tanks into previously Serb-held areas. I liked him because he didn’t just welcome reporters, he understood that we are the first draft of history, and COL Anderson felt if the U.S. Army is making history, someone ought to be there to report it.

We lectured together at the Naval War College one year before. He had invited me, believing young officers needed to know about the media, and how it could even change the shape of a war.

His gift to me was the book We Were Soldiers Once … And Young. It was written by a U.S. colonel and a reporter who together went to Vietnam and wrote it all down. That colonel wanted the bravery and honor of his soldiers told to the world, as did “Strike Six,” Joe Anderson.

Despite the debate about the freedom of embedded reporters, I had agreed to go with the 101st because my friend the colonel promised me “open skies. Don’t give our positions away, but you could broadcast what you want when you want it,” and that’s pretty much the way it turned out.

The 101st was deployed to the war late in the game, just weeks before the conflict began. That meant I arrived in Kuwait before the Screaming Eagles ever got there, so I was waiting at the port when their first of half a dozen ships arrived. The pace was frantic. If the 101st wanted to make the war, they would have to move fast, off-loading a massive amount of equipment to arm some fifteen thousand soldiers, about five thousand of them in the 2nd Brigade. The equipment included two hundred and seventy helicopters: Black Hawks, Apaches, and Kiowas—which make the 101st an Air Assault (AASLT) division.

The ships were late leaving the United States, and the 101st was under intense pressure. As it turned out, all of the needed gear, including humvees and artillery and ammunition, didn’t reach the port of Kuwait until just a couple of days before “G-Day,” the beginning of the ground war. And as we moved out, the Strike Brigade was still receiving its battle gear up to the very last minute, and in the nick of time.

The Desert

The 2nd Brigade was assigned to a temporary staging area in the Kuwaiti desert, appropriately named Camp New York. COL Anderson, a native New Yorker, had me phone the governor’s office in New York and ask for a city flag to be mailed out to our Kuwaiti bureau ASAP.

NBC delivered the flag to Camp New York. COL Anderson carried the flag into battle in honor of those who died in the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001.

The camp was a sprawling series of tents sheltering up to sixteen soldiers. I moved into one tent, with my team of three: producer, cameraman, and engineer Sam Sambeterro.

Sam’s “baby,” as we called it, was a six-foot portable satellite dish that would allow us to feed our video material and go live whenever NBC wanted us to. It also had six New York telephone lines.

Word quickly spread across Camp New York that we would allow free use of the phones, and soldiers who had not seen or talked to their families since leaving the United States lined up to phone home.

Right next to the phones, I had a picnic table that I used to write my stories for NBC. I will never forget those nights under a star-lit sky, listening to young men talk to wives and children and mothers and fathers. There was no way not to listen. It left me with a lump in my throat hearing one young man whose wife was just days away from giving birth to their first child, trying to calm her fears, and another whose father was sick in the hospital.

It still strikes me how wide-eyed and baby-faced the soldiers from the Screaming Eagles appeared while they phoned home.

All of them came to thank me after those calls. Many would tell me they didn’t look forward to war, just the hope it would be a short conflict and they would soon be heading back to the United States.

Missiles

Dressing for war was a complicated balance between not taking enough and getting worn out from carrying too much. One little waist bag I tried never to leave behind was my gas mask. Inside it were self-injecting needles with antidotes to nerve agent (atropine) and antidotes to biological weapons.

The Velcro cover of that bag was worn out within a matter of several frightening days in Kuwait.

The first siren at Camp New York sounded at 1245 hours in the afternoon. We had already practiced the drill of getting into above-ground concrete bunkers, but nothing prepares you for the real thing. You have just nine seconds to get a gas mask out of your bag and put it on, while on the run for that bunker.

As an Iraqi missile screamed over the desert, our hearts raced, wondering if we’d be hit with deadly chemicals, or as one soldier put it—“human insecticide.”

There was silence in the bunker as soldiers waited and wondered and feared. I don’t know what they thought as I tried frantically to call NBC News, and started reporting live as we were under attack.

Over the course of the same day, there were four more Iraqi missile attacks. In one hour, three sirens.

I quickly decided that I would try to stay out of the bunker and report live, which I did, for NBC. It was a personal choice, my reasoning being that if the missile hit our bunker, which had no doors and was open to the outside, we wouldn’t survive anyway. My producer hid in the bunker, and only with a bit of coaxing did I manage to get cameraman Bill Angelucci to come out.

Over the next few days, the rush of adrenaline was followed by fatigue and frustration when the “all clear” signal came. It wore on everyone.

I went from fear to anger; from not wanting to mask-up at all to reminding myself there could be chemical weapons in one of those warheads, which, while falling harmlessly in the desert, could be blown into our camp with lethal consequences.

My producer, who had decided to stay in the bunker, told me she saw one young soldier, tears visible through the gas mask eye pieces. The 3rd Mechanized had passed into Iraq. We were sitting ducks until the word would come for us to move out and into Iraq.

Camp Pennsylvania

Getting psyched up to go into combat is a lifelong pursuit for commanders training young soldiers: how to turn fear into something that motivates. The attack on Camp Pennsylvania, just down the road from our base, bruised the morale of many in the 101st. It was an attack from one of their own, and one of the most confusing sequences of events I had witnessed in the Kuwaiti desert.

An American soldier was alleged to have thrown grenades into three of his commander’s tents. He also opened fire as a soldier tried to come out and investigate the source of the blasts. One soldier lay dead, while nineteen were injured, including the commander.

At Camp New York, there was pandemonium as first word spread of the attack and then another explosion erupted into the night sky. I looked up and saw a huge orange fireball slowly falling to earth not far from our camp. Then the alarm sounded for us to put on gas masks. Soldiers, believing there was a coordinated terror attack on the Camps, took up defensive positions, crawling on the ground around our tent and aiming their weapons at the perimeter fences.

As the hunt was underway for the wanted American soldier at Camp Pennsylvania, in an unrelated incident, one of the camp’s Patriot missile batteries mistakenly identified a British fighter jet as an incoming missile, and launched. We heard the launch, and the fireball I saw turned out not to be a downed missile as we first reported, but the aftermath of two British pilots being blown out of the sky.

Unrelated events, but in the end connected. As soldiers rushed into bunkers, the wanted American soldier who had carried out the attack was seen in a bunker with blood on his clothes, tackled, and arrested.

Despite the obvious news value of the attack, some questioned our reporting, because it actually delayed the departure of the 3rd Brigade. COL Joe Anderson, who attended the memorial ceremony the next day at Camp Pennsylvania, left us behind at Camp New York. His view was, “The story is a day old; we have a war to fight. I can’t imagine why you’re still reporting that.”

The colonel never tried to stop us from reporting, but the incident demonstrated one way of controlling reports coming from embeds. The Army won’t censor your material, but they can control what you have access to. We relied on their transportation, their good will to take us where we wanted to go, and sometimes they weren’t interested in allowing us to see what we thought was news.

Mission Planning

It deserves to be written now that overall, during the war, I was provided remarkable access by the 101st. Not all commanders were as open as COL Anderson. He trusted me as a professional, enough so that I was privy to witnessing the actual mission planning as it happened. I was allowed to walk in and out of what is known as the TOC, or Tactical Operations Center. Inside there were computer screens with real-time information on troop movements. In battle planning, we heard when troops would move before they did. I also saw American intelligence estimates showing the estimated strength and locations of Iraqi forces. All of this helped me cover the war for the American public in a most efficient manner as an embedded reporter.

Because of his confidence in me not to report mission plans, which would surely cost American lives, I can say that the embed process allowed me a deep understanding of the war from beginning to end. I did not consider it a compromise to not report something the moment I knew it. And it was because of COL Anderson’s trust that I came to know that complicated mission plans were often turned upside down.

Almost daily, the 101st received changes in battle plans, and planners became deeply frustrated. 101st MAJ Mike Hamlet, who led mission planning, told me, “I have never seen anything like this in war planning.”

As an example, one day, the 2nd Brigade was tasked to take Saddam International Airport. Another day it was a target code-named BEARS—the road leading out of Baghdad to Saddam’s hometown of Tikrit. In the end, the Strike Brigade was never tasked to take those targets. The 3rd Infantry Division moved faster than anyone imagined and mission plans went up in smoke.

Final Dinner

“Easy Company,” the famous company of soldiers from World War II profiled in movies and TV programs like Band of Brothers, was part of the 101st.

Soldiers from Easy Company told me that when waiting for paratrooper missions in England, they never knew when they would be sent to fight—except for one signal: the night before combat, they were given a special meal. That meant they would go to war the very next day. There were so many canceled missions after these meals that they seemed a mixed blessing.

In a dining tent set up for hundreds, at Camp New York, we lined up for our special meal. Steak and lobster were served to soldiers who now knew they were being deployed to Iraq.

Soldiers from other bases got wind of the menu, and decided they deserved a good dinner, too, so as a result, the lines were so long I never actually tasted the steak. But the lobster tail was the last good meal I would eat for weeks. In the dining hall, soldiers were wearing their chemical (MOPP) suits; the call to move out early the next day had come. There are many stories of the tricky intricate planning in wartime; now I know it goes right down to the last lobster tail served up with melted butter in a tent in the middle of the Kuwaiti desert!

Road to Iraq

The 101st has a saying about how quickly it can deploy: faster, deeper, further. Light infantry, rapid-deployment airborne units can move much faster than heavy, mechanized divisions that need monstrous amounts of supplies to keep them going. We didn’t cross the border first, but when the Strike Brigade moved, it was fast. Traveling only in humvees, we crossed the border into Iraq. Being in the back of a cramped humvee with a cameraman was about as comfortable as being squeezed into a tin can.

Excluding a few fuel stops and eating Army food on the hoods of our vehicles, we drove north toward Baghdad for a straight thirty hours. It was exhausting and nerve wracking. The danger and fear were that Iraqi forces would launch a preemptive assault on our convoy of several hundred vehicles. Humvees are not bulletproof. They are “soft” vehicles and offer little protection, so much of the time we drove at night. No lights. All the while, the drivers were wearing night vision goggles and trying not to fall asleep or run into the vehicle in front.

It is difficult to describe the massive amount of U.S. military supplies moving north. For example, we were told the 3rd ID was literally running out of gas. Huge tankers, convoys of thirty and more, raced up the highway to refuel tanks waiting to assault Baghdad.

One tanker overturned in front of us, when a convoy was told there was intelligence that an Iraqi attack might occur on their roadside base, and they moved out too quickly.

On the road, we saw dizzying amounts of burned-out Iraqi vehicles. And, while it received little media attention at the time, we also saw burned-out U.S. M1A1 Abrams tanks. Soldiers were shocked because no U.S. tanks had been destroyed by Iraqi forces in the last Gulf War, yet outside Baghdad alone we saw three of them damaged beyond use.

The First Mission

The Strike Brigade’s first mission involved relieving mechanized units from the Iraqi town of Kifil, a little town with a very large battle.

Kifil, south of Baghdad and near An-Najaf, is a gateway across the Euphrates River, and where the Iraqis put up a major fight. As we entered the town, the first bridge had been half exploded. We drove across what was left only to find out a few days later there were explosives under the bridge that luckily didn’t detonate as we crossed.

When the 3rd ID quickly pressed forward to Baghdad before us, they often skirted towns and cities, leaving them still occupied by Iraqi Army units and paramilitaries.

Our first meeting with the mechanized units took place on the north side of town, and it ended in mayhem. Iraqi forces, knowing our location, fired mortars on our position.

My cameraman, Bill Angelucci, jumped into a crater left over by the Coalition air campaign, and took cover. I was stuck outside. I first ran for cover beside a building, but then thought the wall might come down on top of me. I ran out into the open, praying the shells now landing 150 feet away wouldn’t kill us.

Within seconds, the Army wisely signaled that we were moving out.

But it wasn’t over. As we drove down the road, enemy sniper fire was directed at soldiers guarding the road. This time I took cover next to a ditch while the soldiers frantically searched for the source of the sniper fire.

All the fears of urban warfare were suddenly realized: The sound of fire echoes off buildings and there’s no way to tell where it’s coming from. You take cover and scan the buildings but often the gunman fires and moves before troops can return fire.

Members of the 101st shook their heads at the damage done by tank fire to the town of Kifil. There was barely a storefront or home along the main street that wasn’t bullet ridden. The bodies of Iraqi paramilitaries shot to death in their vehicles remained. It was a gruesome scene, as starving dogs fed on the bodies.

I will never love dogs quite the way I used to.

Kifil Soda

Kifil, a town most Americans have never heard of, soon became famous among the Coalition troops. The 101st Airborne (AASLT) took over a soda factory as its temporary base. Huge stockpiles of apple-flavored soda, orange soda, and cola soon started appearing on military units moving toward Baghdad. Some soldiers would probably drink that soda before long, in Baghdad!

The Army told us they planned to write a check to the owner of the factory—if he ever turned up.

The Kifil soda factory also bottled water. After days of 100-degree heat, wearing chemical gear that felt like a sauna, we had our first showers. One of the soldiers used a plastic laundry tub and placed it on a second-floor platform inside the soda factory. With a hose as a shower head, and gravity working to draw the water down to the first floor, I was able to get sixty seconds of water.

Ten seconds to get wet and soap up.

Fifty seconds to wash off.

The water was freezing cold.

Still, that soda factory proved to be one of the most comfortable nights we had in Iraq.

Sleeping

When we slept, most of our time was spent on the ground, under the stars, in humvees, or on portable cots—if we could get them.

There were times that we left our gear behind, believing we’d be back to a temporary base—only to be stuck in an area of conflict with nothing. I will never forget the searing daytime heat of Iraq followed by the freezing nighttime temperatures.

In the city of An-Najaf, I slept for two nights on the ground behind a school. With only my clothes and a bulletproof vest to keep me warm, I spent the night miserable and shivering, dreaming the “heater,” or Iraqi sunrise, would come soon. My bulletproof vest often doubled as my pillow. Not very soft, but enough to keep my head off the ground, where I worried about scorpions.

In the end, I only saw one scorpion next to my bedroll, which didn’t bother me. It was a spider that decided I was good enough to eat. For two weeks after the war, I suffered stomach swelling and eventually underwent surgery for the poisonous bite.

An-Najaf—Mines!

An-Najaf is a holy city to the Iraqi Shi’ia, housing the Tomb of Ali, the son-in-law of Mohammed, who the Shi’ia believe was the Prophet’s true successor. An-Najaf was one of the places the Shi’ia rose up against Saddam Hussein after the first Gulf War, only to be slaughtered by Iraqi forces. Soldiers from the Strike Brigade took the city from the north while other members of the 101st fought their way into the southern half.

I stood and watched LTC Bill Bennett from the 101st call in his artillery strikes. The first artillery shells were smoke, to shelter the hundreds of U.S. soldiers moving into residential areas, then came the actual artillery fire directed at the rooftops that were used by the pro-Saddam loyalists to resist the Coalition attack.

Suddenly, out of the smoke we saw a Shi’ia man emerge and approach commanders. He was speaking Arabic while signaling that there was something on the ground we were walking on: land mines!

We had walked onto a minefield, and now we had to get back out. Mines are buried and designed to hide just below the topsoil, until someone steps on them with devastating results. Two of our tanks had already crossed the field safely, so we quickly moved onto those tracks, cautiously walking our way through the danger.

When we got to the other side, our cocky COL Anderson remarked: “Ha! I think that there were no mines—that guy just told us that so we wouldn’t spoil his field.”

Not ten minutes later, there was an explosion as a humvee crossed the field and ran over a mine. Luckily, the passenger seat was empty. The vehicle was destroyed by the blast, but the two soldiers inside the vehicle were unharmed.

LTC Bennett and the others noted how incredible it was the Iraqi risked his life to warn us. It was a sign that the “welcome mat” was out for U.S. forces. But it was also a sign there would be resistance—a lot of it. It was not until months after President Bush declared an end to major hostilities in Iraq that anyone would know how fearsome and costly that resistance would be.

In the streets of An-Najaf the soldiers were guarded. They worried that the residents might try to attack. But as we crossed the road to talk to Shi’ia residents, I was welcomed and surrounded by smiling locals. I was asked for food and water, which the Army couldn’t provide. It was hard to tell people we barely had enough water for ourselves. The Army promised that once the fighting stopped, they would help repair An-Najaf’s water system to win the hearts of the people.

I asked the colonel on camera: “When will you get these people electricity and water?”

“Not our job right now,” he said. “Our goal is regime change; then we’ll see.”

Off camera, the colonel said, “What the fuck was that all about. Why were you bothering me with that?”

But later, U.S. commanders would come to realize that making life return to some normal level in Iraq was critical to winning the long-term battle for Iraqi hearts and minds, and the U.S. government would have to make an investment of tens of billions of dollars in order to do so.

Highway to Hell

An Army commander told me it was going to be a demonstration mission, just a show of force not even worth watching. U.S. soldiers from the 101st, led by tanks from the 2-70 Armor unit, were to drive north from Kifil to distract Iraqi soldiers, while the 3rd Mechanized Division, east of us, would push toward Baghdad.

The plan was called a “fade,” or diversion, so that the Iraqi forces would concentrate on the 101st, while the 3rd ID hit them to the east. No one expected much resistance. They were wrong.

As the tanks pushed north of Kifil, just south of the town of Al-Hillah, Iraqi troops waited in ambush. As one tank commander described it, a “rain of rocket-propelled grenades and machine gun fire” hit the column.

U.S. forces returned the fire and soon artillery exchanges came into play; the big guns from both sides fired 105mm shells, leaving huge craters in the road where they fell. One soldier from the 101st died when he was struck by a bullet while on top of a tank.

A commander told me he hoped he would get a Silver Star from the heroics that day. There were plenty of heroics: the enemy fought hard, and several quick moves limited the U.S. death toll to one. But the next day I was able to talk to soldiers from the 2-70 Armor element. I was surprised at their description of the fight.

One major just shook his head, saying: “It was terrible, a bloodbath, no one wanted to be in that kind of fight.” Tanks were forced, he said, to “open up” on men running at them armed only with AK-47 assault rifles. “We had to shoot dozens and dozens, it was a bloody shooting gallery,” he said as he described the battle.

The 101st Airborne put the death toll on the Iraqi side at two to three hundred. The 2-70 Armor said it was more like one hundred. I wanted to see it for myself.

To get to the scene, I left the 101st and asked the 2-70 Armor to take me north. When we arrived, the carnage on that highway was unforgettable. Burned trees stood as eerie symbols of the death that enveloped everything on the road. There were dead animals that had been caught in the crossfire. The dead bodies of Iraqi soldiers hung out of trucks and jeeps, and were being eaten by insects.

What I will never forget is the smell of death. Many of the Iraqis were killed by tank fire as they fired from buildings. Their bodies remained in those buildings in the hot sun, and the smell hit me like a steamroller.

We witnessed the aftermath of a battle that was seen very differently by the soldiers who fought it. For some it was victory over an enemy. A battle fought and won with honor. But other soldiers told me, “This is not what we trained for.”

Tank commanders who spent their military careers preparing to fight enemy tanks had been forced to cut down an enemy who was driving cars, and in one case, a dump truck.

Make no mistake about it, those cars and trucks and the Iraqis inside them were a threat. They had weapons that threatened tanks, and they killed one American soldier. But it’s just that the fight was one-sided, American forces were so easily outgunning the enemy. Some of the soldiers from the battle will never boast about the fight.

A commander from 2-70 Armor, who didn’t hope for a Silver Star, later got one for that battle.

The Danger

The danger was ever present as we moved through Iraq. In Karbala, as we got ready to join a U.S. infantry patrol to clear pockets of resistance in the city, RPGs (rocket-propelled grenades) were fired at Bradley Fighting Vehicles just a few feet away from my position. The Bradleys returned fire with their 23mm cannons, and I watched as part of the front of a building crumbled before my eyes.

On patrol we often heard sniper fire along with the explosions. That particular day in Karbala, the temperature climbed to over 100°F. We marched with the patrol for six hours. It was almost unbearable. I wanted to drop my bulletproof vest and take off my helmet, but we all knew that just one stray bullet and we would wish we’d had it on. So, I drank as much water as I could and pressed onward.

In Karbala, we had just rounded a bend on the way to a command post, when tanks and soldiers opened fire on a house. The Army was pumping grenades into the front of the house, which was being used as a shelter for Iraqi paramilitaries. The intensity of American firepower was awesome. Soon, the house was burning, and Kiowa helicopters were called in to track the enemy on the rooftops.

Kiowas

The Kiowa is basically a Bell Jet Ranger helicopter, packed with weapons like rockets and machine guns, and electronics that can spot and track enemy positions. They are scouts, though, and are not normally supposed to be the stars of the helicopter war. That’s left to the Apache gunships.

Throughout the Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, though, we constantly saw the fast-moving, low-flying Kiowas flying over and taking the fight to the enemy. The Apaches were, in fact, grounded from night flying by the commander of the 101st. The Apaches often flew on the edges of cities, but because they proved so susceptible to small arms fire in the early stages of the war, rarely did they venture over the urban warfare environment.

We heard several commanders voice their disappointment that the Apaches wouldn’t engage the enemy in urban fighting, all because a general had decided he didn’t want to lose any more to ground fire.

The Kiowas flew directly over the enemy. Kiowa pilot LTC Stephen Schiller of 2-17 Cavalry, and his copilot CW4 Douglas Ford, told me that their helicopter had taken several bullets, including one that lodged directly under Schiller’s seat. He still carries the bullet as a good luck charm.

We couldn’t fly with the 101st’s combat helicopters, but we did have them take one of our cameras along. We aired the video and spoke to enough pilots to realize that the Apaches didn’t have a starring role in the war. The Kiowas won the part, and LTC Schiller received the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Baghdad

Twenty miles outside Baghdad, the 101st was told to stop. COL Anderson expressed frustration with the mission planners back in their bunkers in Qatar, who couldn’t keep up with the battle. Baghdad was being looted and burned, and we could have entered a day earlier than we did, but we had to spend the night at a former Iraqi missile base, waiting almost twenty-four hours before getting the green light to move forward.

Was there a pause in the war? Officially, the Pentagon said “No.” But in the prewar planning, sitting in Kuwait inside the 101st’s Tactical Operations Center (TOC), we had heard about the “pause” over and over again. As U.S. forces approached Karbala Pass, the so-called “trigger point” where Saddam might use chemical or biological weapons, war plans had called for a twenty-four-hour pause, where Hussein would be given a final chance to step down and leave Iraq.

In the end, as we lingered on the edge of Baghdad, there was a pause. But because the war had happened so quickly, and Saddam might already be dead, that “last chance for Saddam” was never issued. But the pause was forced. One 101st Airborne officer confirmed that they “had to pause.”

The Coalition, and the 3rd ID (Mechanized) in particular, had pushed too fast too far, and were out of fuel and ammo. “We, the 101st, had to give them some of our artillery and other stocks so they could push forward. The pause was about resupply, and in the middle of it, sandstorms had swept across Iraq making any further progress impossible,” explained the Screaming Eagle officer.

But, in any event, there was a pause, and battle planners will have to admit one day that the supply lines got strung out, disorganized, and vulnerable to attack. That doesn’t stop the campaign from being anything but a fast victory in anyone’s mind, but it wasn’t quite the ballet Washington had made it out to be.

When we got inside Baghdad, we saw huge crowds of looters on the road, pulling, pushing, dragging, and carrying everything they could from nearby factories and businesses. The 101st did nothing to discourage the looters. The initial decision was made to ignore civil disorder and concentrate on finding the enemy.

We went to one of Saddam’s palaces near the International Airport. We videotaped looters taking toilets, chandeliers, window frames—anything they could pry loose and fit into a car or truck, or carry on their backs. Again, the 101st decided that civil disorder was outside of their mission. It would be several days until the order came to start clamping down on looters.

In Baghdad, the 101st’s lead element claimed a water treatment facility as its new temporary headquarters. Every few days we had taken over schools or factories or slept out in sand dunes; now it was a water plant. It had the first real toilet that we had seen in weeks—no small luxury!

At night in the outskirts of Baghdad, the shooting never seemed to stop. You went to sleep hearing it. I sometimes awakened to explosions coming very close. These sounds remained in my dreams for weeks after I left war-torn Iraq.

Several days into our stay, our compound was fired upon. I was getting ready to go on air—live, with a group of soldiers who had been ambushed the day before, when suddenly automatic machine gun fire sounded over the wall.

Our interview was off. The soldiers began returning fire over the wall at Iraqi gunmen, who shot at the American forces. Incredibly, the fight wasn’t about control of the city; the Iraqi gunmen were involved in a rent dispute. The lawlessness of Baghdad had landed on our doorstep.

The embed process was not perfect. It was, at times, a select but limited window on the war. But it’s important to stress again that we were never censored or stopped from reporting. And all of those small windows from embeds add up to a very big picture, a picture called the Iraq War. It is a picture that without the existence of embeds would never have been provided to the American public.

101st LTC Darcy Horner told me that before the war, when he heard reporters were coming to sleep and eat and live with the military, he responded, “Well, why don’t we just invite enemy soldiers into our bases, too?”

In the end, he saw the media wasn’t the enemy after all.

A young captain from the Strike Brigade turned to me after a day of patrols and fighting in Karbala, and said, “Dana, it’s been an honor to have you with us.” I was surprised. In the first days of the embeds, the soldiers told me they didn’t like the media. Now, after weeks of living together and weeks of facing the same dangers, they had come to see us as friends.

When I told the Strike Brigade I intended to leave them and Iraq, no less than a dozen soldiers told me they couldn’t believe I was leaving. We had become their link to the outside world, and the outside world’s link to the soldiers’ well-being. Their families could know where they were and that they were okay, by watching the news.

The embeds were, and are, the Army’s greatest engagement. Units and soldiers showed how great they could be. Reporters were allowed to slip away from the PAOs (Public Affairs Officers) and get one-on-one with American soldiers, who were well trained and well intentioned.

After seven weeks of being embedded with the 101, I had to admit I felt honored to have had a ringside seat, as gallant and courageous young American soldiers went to war.

I left Iraq and the 101st at the end of April 2003. Soldiers were talking of “mopping-up operations.” The worst was over, or so they thought. The 101st was moved north, to the city of Mosul. In comparison to the fighting, Mosul seemed at first like it would be a cakewalk.

Broke-down Palace

[ROBIN MOORE]

“This is another type of warfare.

New in its intensity; ancient in its origin.

War by guerrillas, subversives, insurgents, assassins.

War by ambush, instead of by combat.

By infiltration, instead of aggression.

Seeking victory by eroding and exhausting the enemy, instead of engaging him.”

—JOHN F. KENNEDY

The 101st Airborne Division (AASLT) entered Mosul on April 22, 2003. The 10th Special Forces Group (A), about a battalion strong, left when the Screaming Eagles arrived, and they pulled out of the area quickly. There was tremendous looting after the collapse of the security forces in Mosul, and one of the early challenges that the 101st had was to reestablish the shattered security.

“It was a fairly chaotic situation when we got here,” said MG David Petraeus, the 101st’s commanding officer.

There had been a riot in Mosul a few days before the 101st arrived. Close to a dozen Iraqi civilians were killed in the riot, after the riot apparently threatened part of the battalion-sized USMC unit that was also here. The riot moved toward the airfield the Marines were guarding, and they felt the airfield was being threatened. Once their duties of securing the airfield were over, the Marines were redeployed back to their ship in the Mediterranean Ocean, and the 101st Airborne took over the AO.

The 101st Airborne is headquartered on the northwest side of Mosul; the airport is on the southeast side of the city, diagonal to it. Initially, the HQ was at Mosul Airfield, but the commander of the Screaming Eagles wanted his men out of “tentage” and into a “hard stand,” because he felt they would be there for a while.

The only place large enough was the palace area of Mosul. Initially, the 101st occupied a small area of the palace complex, which still had residents, or “squatters,” as MG Petraeus referred to them. Internally displaced people, living in bungalows, were given money for relocating before the area was cleaned out.

When the 101st arrived at Saddam’s palace, it had been completely looted. The only things that remained were piles of trash, which were at least ankle deep most everywhere. Everything else was gone. Every light in the place was gone; anything that could be taken had been taken, or had been smashed and destroyed, right down to the toilets and heating systems. Even the copper wire had been pulled through the walls. There was not a single pane of glass left in the entire palace when MG Petraeus and his men arrived. Determined, the 101st rolled up their shirtsleeves and after six months of hard work, the palace was once again organized and functional.

Law and Order

The first month in Mosul was focused on regaining order in the city. The first day, April 22, the 101st met with city leaders and worked out a plan of action. They helped to get businesses open again, put some police forces together and back out onto the streets, and persuaded a retired police chief to take over. “He lasted about a month,” MG Petraeus recalled.

The second police chief lasted only a month, too. As of late October, the third police chief was still there.

The schools and universities were then reopened, and the streets were cleaned. There were private armies and gangs, which needed to be disbanded. It seemed as if every local leader had pickup trucks full of thugs with weapons and heavy machine guns following them around. Before the war had started, all of the power in Iraq was concentrated in the central government. Little, if any, power had been given to the governors of the provinces. They were now scrambling to get whatever they could in the shadow of Saddam’s toppled image.

There were a lot of self-proclaimed “governors,” and with the enormous vacuum in power and the huge number of people vying for control, the 101st came up with a solution. They ran an election, which started in late April and finished on May 5. The election was an intense, ten-day process, and convened 271 delegates for positions on a “Province Council.” Then, the council elected a governor from within their delegates. Sometimes called the mayor, he is “double-hatted” as the province governor and the mayor of Mosul.

The results of early democracy have been great, MG Petraeus said. “It’s quite a representative organization of the people.” The governor was a general who had been forcibly retired in 1993, when his brother and cousin were killed by Saddam. The vice-governor is a Kurd, who was born in Mosul. He did leave the country in the 1990s and returned to Mosul after it was liberated. There are two assistant governors; one is a Syrian Christian, the other is a Turkoman. Two other Kurds are on the Province Council; one is from the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and one is from the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), and there are a number of Syrian Christians on the council, as well. There are sheiks on the council, businessmen, a bishop—really a good cross section of the province.

There are many Arabs both inside and outside of Mosul. The ones inside the city seem to be more technocratic, with the chancellor of the university sitting on the Province Council, along with many doctors, lawyers, dentists, and retired generals. There are actually over eleven hundred retired generals in this province; they made up an important interest group, and had to be represented in the city council.

An important question had to be asked: since these were all Saddam’s generals at one time or another, at what point did they fall out of favor with Saddam? This was key, with regard to their loyalty.

As soon as they saw an Iraqi face as head of their council, the people of Mosul began to take charge of their own destinies, control of their lives, and the rebuilding of their city. “They have a lot of initiative,” MG Petraeus explained. “The governor has already traveled to the UAE [United Arab Emirates]. He’d been to Syria twice, and he helped broker a resumption of trade with Syria that was critically important to northern Iraq’s recovery and reconstruction.”

Major General Petraeus

[ROBIN MOORE—INTERVIEW WITH MG DAVID PETRAEUS]

“Well, fire away!” MG Petraeus, the commander of the 101st Airborne Division exclaimed as the author sat down and pushed the “record” button on his microcassette recorder.

“It’s a fascinating place … I’m not the one to tell how Mosul fell, or the north fell, 10th (Special Forces) Group can tell that far better than I could. The Peshmerga are indigenous to the area above the ‘green line,’ to the east, and northeast of [Mosul]. The Pesh did come down here initially, all around Mosul and all around the Syrian border … cities like Sinjar, and they did in fact secure the huge hydroelectric dam that is to the northwest of Mosul, on the lake.

“There were thousands and thousands of Peshmerga in Ninevah Province when we got here. One of the tasks was to get them back into the Iraqi Kurdish area. In many cases they were, at the very least, an intimidating force to the non-Kurdish population in the areas they were occupying. The Kurdish leaders smoothly coordinated that with the 101st; it took us probably about a month to coordinate the withdrawal of the Peshmerga when we got here.

“The Screaming Eagles had a horrible week in July. Ironically, it was also the time of one of their greatest successes,” MG Petraeus said.

The same week in July that Uday and Qusay Hussein were killed, the 101st lost six soldiers in ambushes planned and financed by former regime leaders. A week or so before the interview, three MPs bearing the Screaming Eagle patch, but detached from the unit and working in the Karbala region, were also killed—supposedly by Shi’ia militia.

The money for ambushes on Coalition troops was abundant in Iraq. An estimated $1.3 million in Iraqi dinars, U.S. dollars, and valuables was found with the bodies of Uday and Qusay. Two nights later, soldiers picked up a Fedayeen Saddam colonel with $350,000 on his person. A massive amount of money was stolen from the Iraqi people, according to MG Petraeus; it is this money that keeps the RPG attacks, bombings, shootings, and improvised explosives used against Coalition troops so prevalent, even now. The one-hundred-dollar reward to shoot an RPG round at some U.S. troops was a month’s pay to most Iraqis, so the offers are tempting, especially for the criminals. Saddam had emptied all of his jails before the war started; the criminals were freed and the prisons were looted. Rebuilding and repairing the prisons of Iraq was another task the Coalition had to master. Moreover, all of the police stations had been burned or completely looted, so the Coalition had to repair or rebuild the stations themselves, in addition to issuing new uniforms, vehicles, weapons, radios, and all of the other equipment a modern police force needs.

In September 2003, a well-armed gang of looters tried to break into a grain warehouse, guarded by Iraqi Security Protection Forces and supplemented by a squad of 101st paratroopers. One of the Americans was killed.

Regardless, MG Petraeus was confident that the Coalition’s mission in Iraq would succeed. “The most important factor is money,” he said.

As of November 2003, there were over twelve thousand Iraqis on the payroll, and the momentum had to be kept up on the reconstruction projects as well. There had been more than thirty-eight hundred different reconstruction projects in the 101st’s sector of Iraq, with costs totaling $29 million through fall of 2003. “Those [projects] are enormously important in the winning of the hearts and minds [of Iraqis],” MG Petraeus said.

Coalition forces anticipate that the various Iraqi Ministries will soon take over part of the financing and payroll, which will alleviate some of the strain on Coalition budgets and help to build Iraqi independence.

An emerging Iraqi independence is evident in the decrease of Coalition presence in some areas—a sign of trust in the new Iraq, and a feeling that Iraqis are able to rebuild and protect their cities and society without a Coalition military presence to back them up. By way of example, for every two ammo dumps still guarded by Coalition troops, there are three that are now guarded solely by the Iraqis. The ratio will only improve over time. “They [Iraqi guards] have been shot at a couple of times, and they shoot back; they do a good job,” MG Petraeus said.

The Coalition presence in police stations has also lessened, from fourteen joint police stations, to just three in November 2003. The rest are Iraqi-run. Gradually the infrastructure is being built up for larger military base camps, so that many of the base camps around Mosul can be broken down and combined into a few larger ones. This will reduce the “footprint” of the Coalition presence on Iraqi soil, and may help ease the frustrations of the Iraqis. The consolidation of base camps also makes it easier for a relief force to take over.

For the Iraqis, training the Iraqis will only become more refined as time goes on. There are two police academies: an interim academy that lasts three weeks and an advanced academy that runs eight to nine weeks. A Primary Leadership Development Course for Iraqi military and police NCOs (Noncommissioned Officers) will be starting up as well.

In MG Petraeus’s opinion, most of the future work to be done will be “repairs,” i.e., the replacement of Iraqi officers, soldiers, guards, or policemen with qualified and properly trained personnel, when they are killed, fired, or injured.

The Iraqi police force was long feared and reviled by the citizens of Iraq for its use of torture, its corruption, and manipulation by Saddam’s regime to do his bidding. The notions of honor, integrity, and selfless service, along with the American police motto, “To protect and serve,” are being indoctrinated in the new Iraqi police. The policemen are now paid a “decent” $120 per month salary when they complete the interim course.

“Is there anything you’d like to ensure is in this book?” the author asked of MG Petraeus as the interview came to a close. “It’s a historical account, and we’d like to have everything in there…”

“Well, just the fact that Screaming Eagle soldiers came in here with a rifle in one hand and a shovel in the other, if you will,” the general replied.

“And I think they’ve maintained, achieved a good balance between killing or capturing bad guys and reconstruction. There’s been a tremendous sensitivity to the need to win hearts and minds. Every operation we do, for example, we test it by asking whether it will create more bad guys than it takes off the street by the way we conduct it. After we conduct an operation, we go back to the neighborhood the following morning, and explain what we did and why we did it, what the results were, ask them what their needs are, hand out Beanie Babies, which are given to our chaplain by the thousands by some supporters on the Internet. Or soccer balls with the Screaming Eagle patch on them, or water, or whatever.…

“Our lawyers have done a phenomenal job, we have a fantastic legal team in everything we’ve ever done … helping to open an international border, or whatever … it’s always done in accordance with UN Security Council resolutions, and all the relevant legal documents out there at any given time. I think again, our commanders and our soldiers work very, very hard to be seen as an army of liberation rather than as an army of occupation. The latest thing that we’re doing right now is we’re conducting about forty-five of what we call ‘goat grabs.’

“A goat grab is basically a local tradition of having a big long table where they put out platters of rice, vegetables, and literally hunks of sheep that have been on a spit, roasting and so forth. You just dig in, you grab sheep or lamb, or fish, or what have you. But we’re doing them, every battalion commander is doing at least one of them, some are doing more. Those are great events for maintaining the engagement with the locals.

“This part of the world is all about personal relationships, and you have to invest in those. We’ve been fortunate to be in the same place for about six months to be able to build those relationships. So, when we have a crisis, we’re more going to meet the Imam for the first time, or the Muktar, the neighborhood clerk.

“We actually brief all of the neighborhood clerks for Mosul, for example, there are a huge number. We do the left bank, and then the right bank, over the course of a two-day period every month. We have biweekly meetings with the Imams, and a biweekly meeting with the Christian bishops. We have a biweekly interfaith council; we have engagement at every level. There’s somebody responsible for everything. You name every function, and there’s somebody responsible for it. There’s medical: the Division Surgeon, and the combat support hospital. If it’s the Telecommunications Ministry, it’s the Signal Battalion … a university has one of our aviation brigades. The school system had … elementary and high schools, separate from the university, had the Corps’ Support Group commander. The Assistant Division Commander of Support does airfields, trains, and taxis and buses. Everybody is overlaid on something …

“We have Civil Affairs battalions, too, and they overlay on these areas in the peace … [Take] a captain, or maybe a major, of a CA battalion, who is doing education—he might be a teacher back home, and now he’s interfacing with a fifty-five- or maybe sixty-five-year-old chancellor of a university of eighteen thousand. And now we take the old colonel, aviation brigade commander, and add him to that mix, and again now, he brings helicopters that can fly this guy to and from Baghdad, he can get him into the office with the CPA [Coalition Provisional Authority] adviser to that ministry. There’s a lot more he can do, plus he has the assets of these command emergency reconstruction programs because he’s an O-6 commander. All of that makes a big, big difference.

“The Division Support Commander does youth activities in most of Ninevah Province. Basically, every ministry activity, we have someone laid on top of, and … ideally, with expertise in it, but if you don’t, then you just put a good guy in and tell him to get after it.

“Because the number one winner, in our slide of winners and losers in Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, are flexible, adaptable leaders and troopers. I don’t know how we get that, but I think it’s partly the American culture. I think it’s partly our military institutions and school systems, and it’s partly just the experience that a lot of our soldiers have had. I mean, a lot of us have done this stuff before. I just came from Bosnia last summer; we were taking command of a division where I spent a year doing this kind of stuff, and also doing counter-terrorism, which is ideally suited for what we’re dealing with when we’re going after the bad guys. That’s really the way we’re doing this. This is not. These are all targeted, intelligence-driven, provided by interagency … fusion. Targeted raids—they’re not dragnet operations, they’re not street sweeps or search-and-destroy or anything like that. They are targeted, focused, and as precise as possible, operations.

“And, by the way, we take the Iraqi police and the Muktars with us whenever we can. We don’t [search] mosques, the police will [search] a mosque for us … that was said in the slide briefing yesterday. We don’t [search] women; we have women soldiers who do that, or again, the police … it’s just an extraordinary team of people to have in the 101st, and all the additional assets given to us. And then, the great Iraqi partners, who have really stepped up to the plate, and so forth. And really, again, I just can’t say enough about the team that has been provided to us here, and how fortunate we are to have such talented people, at all levels.

“But you’ve got to go after the bad guys at the same time, because they are trying to come in and take down what is, you know, arguably a success story for Iraq. Certainly the Iraqis here feel that they are leading the way for the rest of Iraq. They are ‘setting the standard,’ to use a military term.”

HVT #2 and HVT #3

The second and third most-wanted Iraqis, HVT (High-Value Target) #2 and HVT #3, were none other than Uday and Qusay, the two sons of Saddam Hussein. For months before the raid that killed the sons, U.S. forces, and in particular a super-secret Special Operations Task Force (SOTF), had been hunting high and low for the fugitives, chasing down false leads and keeping intelligence efforts at full force.

Uday Saddam Hussein was, at one time, the infamous chief of the Fedayeen Saddam, the Iraqi Olympic chairman, and an Iraqi National Assembly member. His torture of Olympic athletes, documented in Sports Illustrated magazine, was especially cruel, and gave the world a glimpse into his realm of power and horror. Reports have described Uday as punishing athletes who lost a game, with severe jail sentences during which they were beaten and tortured. One particularly gruesome method of torture was to have athletes dragged across pavement or a rocky surface, then dipped in blood and sewage to ensure infection.

During Operation IRAQI FREEDOM, Uday was known as “the Ace of Hearts,” and his picture was in the hands of every Coalition soldier with a deck of playing cards issued by United States Central Command.

Uday founded the Fedayeen Saddam, “men of sacrifice,” in 1994 or 1995 (reports vary) to support his father against domestic opponents and crush potential dissenters. The Fed-ayeen also performed anti-smuggling operations and patrols, and their ranks were filled with young, promising, idealistic soldiers from pro-Saddam regions of Iraq.

According to intelligence reports, Uday was relieved of command in September 1996 when his father discovered that he had been transferring high-tech weapons from elite Republican Guard units to his Fedayeen militia. Control was passed to his brother Qusay. Not only were the Fedayeen Saddam royal guards, but the thirty thousand to forty thousand martyrs reported directly to the Presidential Palace instead of the army command, and were well trusted and politically reliable.

Qusay Saddam Hussein was designated “the Ace of Clubs.” In 1996, he took the reins of the Fedayeen from his brother, which added to his power and control of Iraqi intelligence. Qusay was also the supervisor of Al Amn al-Khas, or Special Security Service (SSS), and the deputy chairman of the Ba’ath Party’s Military Bureau.

The SSS (also called SSO—Special Security Organization, or the Presidential Affairs Department) was described as “the least known but most feared Ba’athist organ of repression.” Its official function was to protect the Ba’ath leadership, most importantly Saddam. Unofficially, according to reliable sources, including Jane’s Intelligence Review, the SSS secretly set up a network of front companies to acquire special equipment and materials used in the production of chemical, nuclear, and biological weapons during the 1980s.

The SSS also conducted surveillance on members of the Iraqi military and intelligence officers with sensitive positions. They were the most trusted of Saddam’s elite, and held a special position with special rewards—especially the SSS members who survived and protected the leader during an assassination attempt. The only people that Saddam trusted enough to supervise these highly secret organizations were his own sons. That alone granted them status as Numbers Two and Three on the Coalition’s target list.

* * *

On June 29, 2003, Uday and Qusay Hussein arrived at the door of a huge stone and concrete home in the Falah district of Mosul. The two sons arrived with five others; they were all wearing traditional off-white Arab dress, called dishdashas. Uday had shaved his head and sported a curly “Quaker-style” beard without a moustache. Qusay sported longer hair and the early growth of a new beard. Also with them was a man named Summet, believed to be a bodyguard, and Qusay’s fourteen-year-old son, Mustafa.

The party arrived in two separate vehicles: an extended-cab, four-door white Toyota pickup, and a black Mercedes-Benz. The next day, the Toyota’s Baghdad license plate was changed to a Tikrit one. According to the tipster who ratted on the infamous brothers, the license plates were swapped frequently.

When the tipster came to the 101st, he provided quite a lot of information. Initially, the 101st didn’t believe all of it: it was just too good to be true. The informant told of Uday’s and Qusay’s requests for him to steal another car and get more weapons, and explained how the brothers were plotting to send a car packed with explosives into the Ninevah Hotel in Mosul. They also wanted the tipster to score them some phony Syrian passports.

COL Joe Anderson, 2nd Brigade’s commander, immediately contacted Task Force 20, the secret operations group tasked with hunting down Saddam and his two sons. The brothers had already been holed up in the house for about three weeks longer than they originally told the source they had expected to be. Letters were brought back and forth between the sons and people on the outside, and the source claimed that he had heard conversations he believed were with Saddam Hussein himself.

The sons of Saddam and their henchmen brought bags and pieces of luggage with them. One bag alone, about two-by-two feet in size, was stuffed full of American dollars and Iraqi dinars, totaling $500,000. Another bag full of jewelry was found under the bed that Qusay had been sleeping in. Additional bags contained five assault rifles and one RPK light machine gun.

For three weeks, Uday and Qusay remained holed up in the house, and according to the tipster, sometimes stayed up all night long plotting attacks against U.S. forces. On July 19, Qusay’s son, Mustafa, left the house, walking from the hideout with another of the henchmen, a man named Munam. Munam was Summet the bodyguard’s brother, and the former manager of Saddam’s palace in Baghdad. Mustafa and Munam returned the next day with a white four-door Toyota, and two bags of clothing.

The Raid

The operation began on July 22, 2003, at precisely 1000 hours. The cordon was in place; the 101st’s 2nd BDE (Brigade) had a support-by-fire position on the south side of the building and a support-by-fire position on the northeast side of the building. There were additional troops situated on the road parallel to the target house.

The assault force from Task Force 20 was standing by, three buildings over, ready to move around and storm into the target house when the time came.

An interpreter with a bullhorn was used to contact the targets from a position right next to the garage, the entranceway to which was situated near the front door. Vacant lots were on either side of the house, and the Bashar Kalunder mosque was located diagonally to the house, across the street.

This was a wealthy neighborhood. From the air over Mosul, green lawns could be seen behind the high, gated stone and stucco walls that surrounded most of the houses. All of the houses had two stories, with patios on the flat, low-walled roofs. Also worth noting was the width of the streets, with large sidewalks and multiple lanes. This was a neighborhood of privilege.

The only people in the target house at the time of the assault were Uday and Qusay, the bodyguard, and Mustafa’s son. The owner of the property, Nawaf al-Zaidan, owned a total of five houses. He purportedly was a self-proclaimed cousin of Saddam Hussein; a lie that led to his being jailed years ago. But he did have business associations with the family, under the auspices of the UN Oil-for-Food program, which eventually led to Uday and Qusay seeking refuge in his house.

At 1010 hours, Task Force 20’s assault force came around the northern, rear side of the house, into the carport. They had just begun working their way into the building when they came under fire from either assault rifles or light machine guns.

Four soldiers were hit; three were Task Force 20 operators on the way up the stairs, and one was a 2nd BDE trooper in the street, felled by a round from the Hussein bodyguard, who fired from an upstairs bedroom window.

A Black Hawk medevac chopper dusted off from a nearby field to evacuate the four men wounded in the firefight. The first entry was botched.

At 1030 hours, the 101st opened up on the hideout with their vehicle-mounted, .50 caliber machine guns to soften the fugitives, so that Task Force 20 could attempt another entry. Again, the return fire from inside the house held them at bay.

At 1045, COL Anderson cranked up the heat. AT-4 rockets were eagerly pulled from rucksacks, and the air rang with the clacks of charging handles from the vehicle-mounted Mark-19 automatic grenade launchers that surrounded the residence. The Screaming Eagles started to “prep” the hideout a little more before TF 20 moved in for another go at it. Even light antitank rockets and 40mm HE grenades weren’t enough, however; return fire from the house continued.

By 1100, COL Anderson had called up a team of two Kiowa Warrior helicopters on the radio. The Kiowas flew from an airfield about an hour’s drive south of Mosul, zeroed in on the target house, and armed their weapons systems. The lightning-fast gunships came from southeast to northwest, screaming toward the house as they let four 2.75-inch rockets and their belt-fed .50s loose. One rocket struck pay dirt, while three arced wide and to the left, missing their mark.

“It was unusual for this many rockets to miss,” Anderson said. “But this is July, and they hadn’t fired any since April.”

Also, the Kiowa is very unstable when firing, because of its slight stature. Kiowa pilots prefer not to fire their weapons systems at all while hovering.

The Kiowas made one more gun run before the QRF (Quick Reaction Force) platoon was called in. A platoon from the “Widow Makers,” 3/502nd (3rd Battalion, 2nd Brigade) of the 101st, was in position downhill by the river, and moved up at 1150 hours. A tactical Psychological Operations (PSYOPS) team and the Military Police’s QRF team were also on the move. Blocking positions were set up along the south of the house to hold back the crowds gathering to watch Targets Number Two and Number Three make their last stand. Later in the day, one of the people in the crowd fired at the American soldiers.

At noontime, shots rang out from a two-story pink building across the street, which had a store below and some apartments on top. Five minutes later, Task Force 20 made another move. They moved in the same way as before, and again took fire when they topped the stairs inside the house. This time, Task Force 20 retreated to the north, to a home across a parking lot.

Next, COL Anderson ordered “Prepping, Phase Two” on the holed-up Hussein sons—.50 calibers and Mark-19s were again on the menu. Fifteen minutes later, TOW (Tube launched, Optically tracked, Wire guided) missiles—among the heaviest weapons they had—were launched. Volley fires were aimed at the house, and eighteen TOWs flew in from every which way, impacting the mansion and punching holes through the structure’s two-foot-thick concrete walls.

The goal of the eighteen-missile volley was, according to COL Anderson, “A combination of shocking them if they were still alive, and damaging the building structurally so that it was unfeasible to fight in.”

Task Force 20 had reported that there had been a stronghold-type safe room near the bedroom, probably specially reinforced and designed with a “last stand” in mind. On their first entrance attempt, there was movement from a sitting room and a room by the corner. When Task Force 20 soldiers once again entered the house, there was no movement at all.

All four inside were dead. Blasted furniture was everywhere, and the walls were pockmarked and gouged with bullet holes, or completely blown out altogether by grenades, rockets, and missiles.

The house was bulldozed the next day, because the building was not structurally sound after all the explosions. Columns that had framed the front of the house were now skeletons of rebar and wire. Also, the razing of the structure would keep souvenir hunters out of the area, where they could potentially get hurt.

In a later interview with COL Anderson, he talked about the raid that resulted in the deaths of Uday and Qusay: “We had a tip they were in the house. But we had many tips like that before. I just knew we had some bad guys when our soldiers approached the house and they opened up from the balcony. They fired on some of our soldiers, wounding several.”

However, did the Coalition want to kill Uday and Qusay, or capture them alive? To this question, a senior officer in the 101st ABN (AASLT) replied, “We just kept ramping it up in response to them. They obviously were not going to give up. I had wounded men. They fired; we fired back. I brought in more and more soldiers. They fired more. I ramped it up more. Eventually, we put antitank missiles through the window. That was that.”

The officer also stated that violent raids such as the showdown with Uday and Qusay might have been a mistake by those above (i.e., Administrator L. Paul Bremer III) to attempt to very quickly alienate the former Ba’ath Party members. Many of them had felt disenfranchised by the new Provisional Authority. With no promise of a new future, Ba’athists eagerly helped in the insurgency. “The important question is, What are your intentions now?” Bremer had said. “Based on certain professions, there was a big pool of Ba’ath (like schoolteachers); you just can’t say the guy was Ba’ath. It’s, What does that mean now?” Bremer explained. “Were you a dues-paying member, or an active supporter of the [Saddam] regime?”

By the end of the year, Bremer had softened his stand on Ba’ath Party members, allowing them to join the new Iraq Army and the police force in what the United States dubbed the “de-Ba’athification” of Iraq.

A Touch of Home

The morale of the troops in any war zone is absolutely vital. It is said that an army marches on its stomach, but an army in good spirits can go hungry in a pinch, and can succeed where others would fail, often against overwhelming odds.

The war in Iraq had generated mixed reaction among the Democrats and Republicans, the liberals and the conservatives. But when the commander in chief makes the decision to put our soldiers’ lives on the line on a new front in the Global War on Terror, the public should be behind these brave servicemen and -women 100 percent. By their very nature, our troops are without opinion; they must follow orders, and do their best in the situation they have been given. Thus, troop morale is of the utmost importance.

The confidence of the troops can be raised in many ways—mail from back home, and care packages full of candy and treats do much to warm the spirits. But when mail call is held one day a month, if the troops are lucky, there is often the fearful anticipation of a “Dear John” letter, or none at all. Some soldiers would rather not hear from their loved ones at all, until they are home safe in the arms of those they cherish. It is often too much to bear, and too distracting when on the front lines of combat.

But one thing that the soldiers would never complain about is a good old-fashioned USO-style concert. Any celebrity who could entertain the troops while they are at war would boost their spirits and be burned in their fondest memories until their final day. And one of the toughest parts of being a soldier is the uncertainty of not knowing just when that final day will be.

People in the public eye may have ulterior motives for wanting to visit Iraq, and the American public is not blind—the crossed fingers of young soldiers while shaking the hand of Hillary Clinton can attest to that. Some people may have criticized President George W. Bush for landing on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln to announce the ending of open warfare against Saddam’s regime, but it will forever bring a smile to the faces of those who were there serving their country, and that is most important.

As this is being written, President Bush’s father has planned to parachute out of an airplane to celebrate his eightieth birthday. This won’t be the first time—the former president was shot down south of Japan in World War II and parachuted to safety, by necessity. But in 1997, thanks to publicist and media whiz Linda Credeur, Bush Sr. was inspired to do it once again, finally bringing closure to the bad memories. The former president’s eightieth birthday, on June 12, 2004, will hopefully mark the third jump he has made since his bailout during World War II.