Jackson Pollock in his studio in Springs, New York

Photograph by Hans Namuth (1915 – 90)

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner Papers, ca. 1905 – 84

Jackson Pollock in his studio in Springs, New York

Photograph by Hans Namuth (1915 – 90)

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner Papers, ca. 1905 – 84

In the popular imagination, artists are romantic, exotic beings who live glamorous lives far removed from the ordinary ones the rest of us experience. This impression is reinforced by the tradition of formal portraiture staged by professional photographers for mainstream publications: artists usually pose in their studios, work tools at hand and surrounded by their art, as though the creative muse could fall upon them at any moment. Such portraits of artists paradoxically combine a sense of gravity and ephemerality, their apparent seriousness and materiality balanced against the evocation of transcendence, of expression unfettered by conventionality.

Carefully planned, these photographs once pictured artists dressed in berets and sculptor’s smocks or, more recently, in denim overalls and paint-smeared work shirts. Sometimes incongruous props appear: vases of flowers, brocade tapestries, a table piled with books. The artists lean jauntily or stand heroically, staring intently at the camera or gazing out a window as if at some distant vision, all to build or conform to an image of the character we have come to know as “artist.” With the rise of hand-held cameras, which replaced the portrait photographer’s large studio cameras on tripods, the iconic image became an action shot, which happily coincided with the birth of action painting. We have only to give it a little thought to conjure up a mental picture of one of the images Hans Namuth made of Jackson Pollock flinging paint onto a canvas. Here is Pollock, caught by the camera in mid-gesture, his brow furrowed in the anguish of creation: the quintessential portrait of the artist in the mid-twentieth century. In our own time, learning how to present oneself to the camera has become a part of every artist’s skill set.

Consider, however, another look at Jackson Pollock in photographs. Judged by the number of snapshots now in collections at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, the Pollock family, especially the brothers Jackson and Charles, must have had a camera present nearly full-time as they grew up in the western United States in the 1920s.1 In 1945, when Jackson and his wife, the artist Lee Krasner, moved from New York City to the east end of Long Island, a camera came, too. Domestic photos of Jackson and Lee (it remains for us to guess who might have wielded the camera) are guileless and revealing, as are the images of Jackson outside his studio with his two dogs, horsing around in the backyard, or on the beach with his friends (a group that includes the influential critic Clement Greenberg and his girlfriend of the time, the painter Helen Frankenthaler). These snapshots have a backstage glamour all their own, as clear an everyday picture of the artistically famous as we might hope to have.

— 1927 —

Jackson Pollock cutting the hair of his father, LeRoy Pollock

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, ca. 1905 – 84

— 1950 —

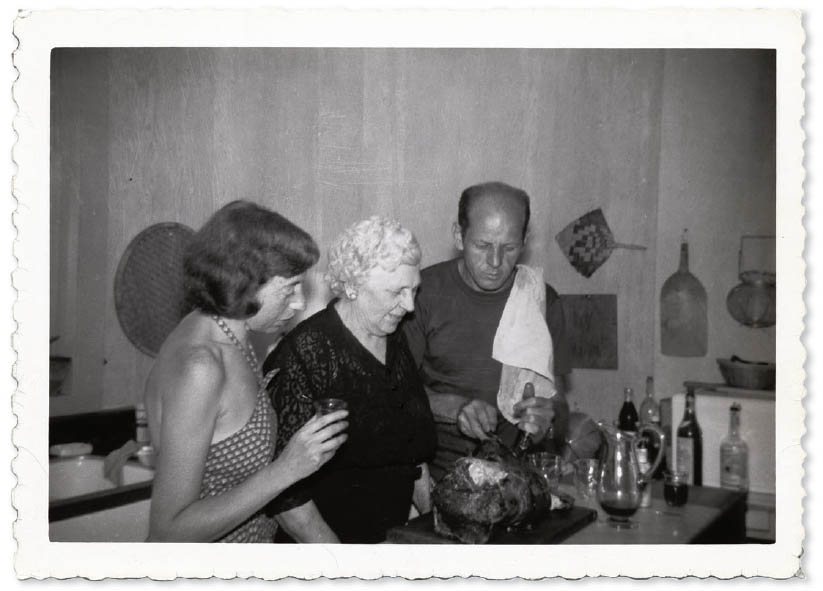

Lee Krasner, Stella Pollock, and Jackson Pollock carving a turkey

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, ca. 1905 – 84

The early twentieth-century advent of the Kodak Brownie—considered by most historians to be the first snapshot camera—made photography accessible to a widespread public for the first time (a feat of cultural diffusion magnified many times over in our time by the introduction of smartphone digital cameras). In the parlance of vintage Kodak advertising: you pressed the button, and they did the rest. Formal portraits taken by professionals were supplemented in the vaults of memory by family albums filled with snapshots taken by untrained but earnest hobbyists. As photography became more and more an everyday activity, everything and anything became a worthy target for the camera. By the middle of the twentieth century, amateurs began to see their picture taking as a way not only to document themselves and their families, as well as the places and things most important to them, but also to define and even transform themselves. For artists it was the same.

There is no question that snapshots can be compelling and complex, even unintentionally. After years of being neglected by historians of photography, snapshot images have become objects of aesthetic fascination, cultural nostalgia, and critical discourse. In our digital age they have been the focus of a number of substantial publications and exhibitions.2 The postures we adopt, the gestures we pantomime, the camera’s odd tilts, and the images’ arbitrary croppings—all are part of what has become known as the “snapshot aesthetic.”3 These images are both familiar in format (most of us have snapshots of one kind or another tucked away) and alien in content (while we might recognize the conventional pose of a family gathered around the picnic table on the Fourth of July, the faces are unfamiliar). They provide historical access—if not always factual—to cultural, political, and social trends (the rise of the middle-class family and outdoor recreation, say), while they encourage the viewer to construct a story to describe the people or events in the picture (why was that little girl on the left crying?).

The mostly casual, unassuming snapshots in the collections of the Archives of American Art offer a special genre of artist portrait, as well as (for those involved in charting art history) surprising insights into artists’ personal lives. They depict families, friends, and lovers. They picture celebrations and parties that mark proud public moments and intimate private ones. They show artists being silly, thoughtful, and showing off. With them we visit the world of studios and galleries. We know the identities of these pictures’ subjects and often where the images were made, which is frequently not the case with the snapshots in our own family albums. Armed with such information, we use the lens of retrospection to consider these subjects in the context of what happened later, long after the snapshot was made. Snapshots offer entry into the biographies of artists.

The photographs selected for this book—most from the golden age of film-and-paper snapshots, the 1920s through the 1960s—include those taken informally by artists in the company of other artists, in their studios, and at events that give us a sense of the art world of previous generations. These photographs, rich in connections and implications, might find their way into art-history texts in the future.

This book is loosely arranged around four themes, assigned to four chapters, “Work,” “Play,” “Family & Friends,” and “This is Me!,” based upon the various situations and impulses common to the images.

“Work” captures artists in unguarded moments in their studios, outdoors at their easels, at the art colony. Or at the art gallery, where the activity of openings—artistic work of a certain sort—and the boisterous celebrations that follow are frequently captured by the camera. These unguarded moments give us a real, if brief, look at the artistic process.

The snapshots in “Play” provide rare glimpses of what artists did in the privacy of their homes and how they played when they were away. Through these images, the lives of artists become available to us. For a moment, we feel connected to these people and their lives, which are not so different from ours.

The snapshots in “Family & Friends” emphasize a narrative about connection, community, and interaction. Recording the family for posterity is one of the most common motives of snapshot photography. Kodak advertisements from the early twentieth century stressed photography as a means to record activities and moments of family togetherness and to counter the failure of memory.4 Just like the rest of us, artists have filled their family albums with images of children, vacations, and the gatherings of friends and relatives for celebrations. Perhaps these are particularly valuable for artists, who so often live in a peripatetic world: snapshots are a way of creating stability through the memories they hold. From artists, however, the sentimental forget-me-not messages of ordinary snapshots often are more like a “Here I am!” declaration. What matters is the documentation of the occasion; the picture-taking act itself has become a part of the ritual of meeting and greeting.

Every photograph marks an instant in time. It both confirms and recalls the reality of that moment. It declares on behalf of both photographer and subject, “This is me!” The images in the fourth and final section embody those messages, from Ansel Adams’s forthright Photomatic self-portrait to early snapshots of the abstract expressionists, which provide fresh views of their then-new and radical work. In the extensive snapshot archives of gallerists Colin de Land and Pat Hearn, we trace day-to-day details that combine to form visual diaries not only of the couple’s personal lives, but also of an entire artistic community. Their self-conscious and insistent use of a camera comes close to being a conceptual art project.

In the hundred years this survey encompasses, snapshots have gone from novelties documenting the experience of a fortunate few to the currency of everyday experience, now omnipresent and inescapable in the form of smartphone photos, circulated almost at the moment they are made—sped-up Polaroids for the digital age. Snapshots have transformed from signs of artists’ common humanity to part and parcel of what art is and what artists are. What has stayed the same through all this change is the beguiling charm of the pictures themselves: whether they represent offhand moments or implicate artistic intention, the snapshots you are about to see have a purchase on the viewer’s imagination that simply won’t go away.

1. Several family collections contain Pollock family snapshots: see the Charles Pollock Papers, 1902–90; Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner Papers, circa 1905–84.

2. This book is based on the exhibition Little Pictures, Big Lives: Snapshots from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, July 1 – September 31, 2011. A list of recent books and exhibitions about the history and culture of the snapshot includes: Thomas Walther and Mia Fineman, Other Pictures: Anonymous Photographs from the Thomas Walther Collection (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000); Sarah Greenough and Diane Waggoner with Sarah Kennel and Matthew S. Witkovsky, The Art of the American Snapshot, 1888–1978 (Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 2007); Marvin Heiferman, Nancy Martha West, Geoffrey Batchen, Now Is Then: Snapshots from the Maresca Collection (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2008); Elizabeth W. Easton, ed., Snapshot: Painters and Photography, Bonnard to Vuillard (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2011); and Catherine Zuromskis, Snapshot Photography: The Lives of Images (Cambridge, MA: The mit Press, 2013).

3. John Szarkowski uses this phrase in discussing the work of Garry Winogrand. John Szarkowski and Garry Winogrand, Winogrand: Figments from the Real World (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1988). According to Matthew S. Witkovsky, writing in The Art of the American Snapshot, the origins of the term in literature of the mid-1960s have yet to be pinpointed (288).

4. For a full discussion of the role of Kodak advertisements and the development of snapshot culture, see Sarah Kennel, “Quick, Casual, Modern: 1920–1939,” in The Art of the American Snapshot.