Two early twentieth-century studio photos made in a casual, snapshot style describe the interests of Allen Tupper True (1881–1955) and Newell Convers (N. C.) Wyeth (1882–1945), fellow students of Howard Pyle at his Wilmington, Delaware, school of illustration. The romance of the West inspired both young men. Their studios were full of cowboy costumes and Native American artifacts, many of which wound up as details in their paintings and drawings. Wyeth, who was best known as an illustrator of American subjects for magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post, even worked for a time as a cowboy, returning east with cowboy costumes and Native American artifacts to feature in his work. True, who became a mural painter, specialized throughout his career in Western themes.

— ca. 1901 —

Allen Tupper True in his Delaware studio

Allen Tupper True and True Family Papers, 1841 – 1987

— ca. 1905 —

N. C. Wyeth in his Delaware studio with Allen Tupper True modeling as a cowboy

Allen Tupper True and True Family Papers, 1841 – 1987

This spontaneously posed picture shows the painter Andrew Dasburg (1887–1979, left); an unidentified visitor; and possibly Roland Moser (right), Dasburg’s studio mate, cleaning dishes after a meal in Dasburg’s Paris studio, at 115 rue Notre Dame des Champs. The image suggests the makeshift life of an American artist in Paris circa 1910. Like many aspiring American painters, Dasburg sought out experience in the then-capital of the art world. In fact it was a return home for Dasburg, who was born in France and taken to the United States as a young child. Returning to New York City after only one year, Dasburg became prominent in New York art circles and was among the youngest artists to exhibit at the International Exhibition of Modern Art in 1913. He also showed his work at Alfred Stieglitz’s 291 gallery. In 1916 he made the first of many visits to Taos, New Mexico, settling there permanently in 1930.

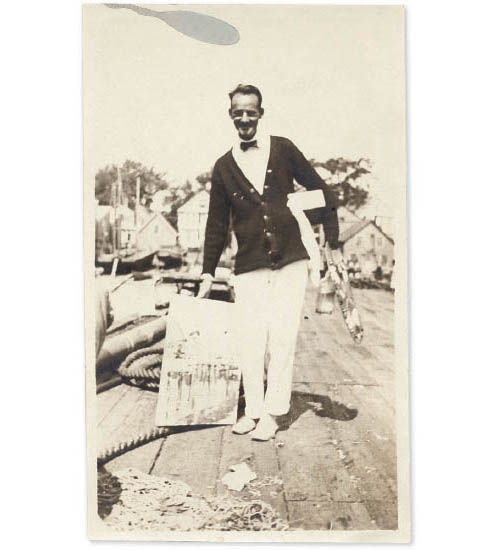

Presenting objects for a camera is something all of us do. Usually these objects are a source of pride—a shiny new car, the big house we just bought, the treasure we just found at the flea market. Think, too, of all the snapshots of new babies held up for the camera by proud parents. Artists’ most prized possessions are usually their own artwork; sometimes they relate to their creations as if they were their children. Sometimes the artwork is a performance of the self that is put on show for the camera, a visual reminder of the artist’s presence.

— ca. 1910 —

John Robinson Frazier carrying a painting

John Robinson Frazier (1889 – 1966) was a painter, illustrator, and art school administrator. He served as president of the Rhode Island School of Design from 1955 to 1962.

John Robinson Frazier Papers, 1920 – 69

— undated —

Gertrude Abercrombie sitting on steps with her artwork

Gertrude Abercrombie Papers, 1880 – 1986

— undated —

James Penney holding a painting on a roof

James Penney (1910 – 82) was a landscape painter, muralist, and educator who taught at Hamilton College from 1948 to 1976.

James Penney Papers, 1913 – 84

Robert Mangold in his New York studio

Robert Mangold (b. 1937) is a painter best known for minimalist, abstract works of architectural scale.

Fischbach Gallery Records, 1937 – 77

— ca. 2000 —

Unidentified individual holding a Polaroid

Colin de Land Collection, 1968 – 2008

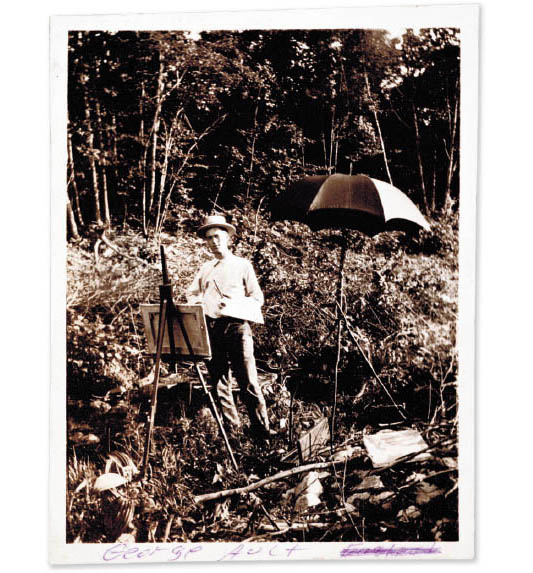

The majority of snapshots worth saving combine good intentions and good luck with engaging subjects. Most of the time, we can never know exactly what occasioned their making. The unguarded moments snapshots reveal of artists at work in their studios, outdoors at their easels, or teaching give us behind-the-scenes glimpses of the artistic activity that some may call work and others play; in the best instances, snapshots tell us something about both the artist and the art.

— ca. 1920 —

George Ault painting outdoors

George Ault (1891 – 1948) was an American painter whose style was shaped by his interest in a curious mix of the avant-garde, realism, and folk art.

George Ault Papers, 1892 – 1980

— 1911 —

Walt Kuhn painting outdoors in Ogunquit, Maine

Walt Kuhn, Kuhn Family Papers and Armory Show Records, 1859 – 1978

In 1932 Grant Wood (1891–1942), Edward Beatty Rowan (1898–1946), and Adrian Dornbush (1900–1970) founded the Stone City Art Colony near Cedar Rapids, Iowa. With little more than a hundred dollars they leased ten acres of land, which included buildings for sculpture and painting studios. For living quarters, the camp boasted wooden icehouse wagons, many of which were imaginatively decorated by the artists. The colony lasted only two years—perhaps the wagon arrangements had something to do with this—but Stone City, led by Wood, still assembled a distinguished and enthusiastic population.

— 1933 —

Students and faculty at the Stone City Art Colony

Grant Wood and John Steuart Curry (1897 – 1946) are in the front row.

Edward Beatty Rowan Papers, 1929 – 46

— ca. 1933 —

Grant Wood putting the finishing touches on his ice wagon

Edward Beatty Rowan Papers, 1929 – 46

Born in Japan, painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi (1893–1953) immigrated to America in 1906, stopping first in California and then moving east to attend the Art Students League of New York, where he would also become a teacher. To supplement his income he did commercial photography—mostly shooting artwork for galleries and catalogs. He moved to the Woodstock art colony with his first wife, artist Katherine Schmidt, in 1927. They built a house and enjoyed the relaxed community of artists. His friend and Woodstock neighbor, painter and photographer Konrad Cramer (1888–1963), also shot his friends’ artwork and commissioned portraits, as well as informal photographs such as this one of a smiling Kuniyoshi. No photograph of Cramer by Kuniyoshi can be found, but perhaps the two were enjoying an afternoon of photography, taking turns as subject and photographer.

— ca. 1940 —

Yasuo Kuniyoshi taking photographs

Photograph by Konrad Cramer

Konrad and Florence Ballin Cramer Papers, 1897 – 1968

The tilt of this lively picture mimics the motion of a Calder mobile in space. Agnes Rindge Claflin (1900–1977), the author of an authoritative book on sculpture published in 1929, was an art historian at Vassar College and had just been named director of the Vassar College Art Gallery when she visited her friend Alexander Calder (1898–1976) in his studio at the Calder farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut. The mid-1940s were an important time for both the scholar and the artist. In 1943 Claflin became an assistant executive vice president of the Museum of Modern Art. In the same year the museum organized an exhibition of Calder’s sculpture, a project that included a film, Alexander Calder: Sculpture and Constructions, written and narrated by Claflin. Could the push she seems to have just given the mobile be something of a test for her film project?

— ca. 1942 —

Alexander Calder and Agnes Rindge Claflin in Calder’s studio in Roxbury, Connecticut

Agnes Rindge Claflin Papers Concerning Alexander Calder, 1936 – ca. 1970s

In the aftermath of World War II, even as the art world’s center shifted from Paris to New York, students and artists such as Esther Rolick (1922–2008) descended on Paris and the art capitals of Europe in search of inspiration and a connection to the past. They were also motivated by a sense of nostalgia for the experiences and achievements of the Lost Generation of the 1920s, which had been drawn to the Old World’s tolerance for experimentation and artistic freedom. After Rolick’s return to New York, her work appeared in exhibitions that included a one-person show at the Jacques Seligmann & Co. gallery in 1953. And, perhaps most importantly, she taught art, imparting the joys of artistic freedom to young American artists. Her course “Black Music and Art,” taught at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, New York, in the early 1970s, was full of insights she gleaned from interviews she conducted with a generation of African American artists.

— sept. 1948 —

Esther Rolick on board the SS Saturnia

On the backs of these three snapshots, Esther Rolick wrote: “My first trip to Europe.” How many American artists were thrilled to be able to make this simple claim?

Esther G. Rolick Papers, 1941 – 85

— 1945 —

Sculptor Wessell Couzijn and Esther Rolick in Rolick’s New York studio

During World War II, the studio of painter Esther Rolick was a sanctuary for artists such as sculptor Wessell Couzijn (1912 – 84), who had been forced to flee Europe by the Nazis.

Esther G. Rolick Papers, 1941 – 85

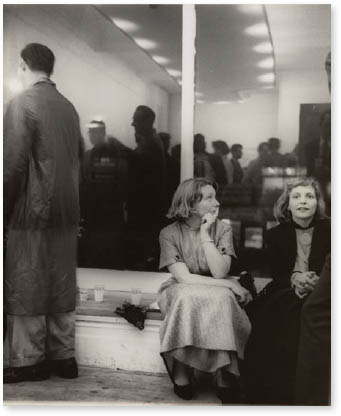

What a wonderful moment: Elaine de Kooning (1918–89) holding forth at the center of a circle of male artists during a 1956 opening at the Tanager Gallery in New York City. Maybe the conversation was about her inclusion that year in the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition Young American Painters, an event that certainly marked her as one of the boys. The Tanager, which operated on East Tenth Street from 1952 to 1962, was among the group known as the Tenth Street Galleries, a community of artist-run, generally low-budget galleries and studios that opened and closed throughout the 1950s and ’60s. Making exhibition space available to a wide range of painters and sculptors, with a number of older, more established artists such as de Kooning’s husband, Willem de Kooning; Franz Kline; and Milton Resnick as neighbors in nearby studios, these venues were an avant-garde alternative to the more conservative uptown galleries. Then, as now, artists’ neighborhoods such as Tenth Street were places to meet and mingle. Evening openings were a mix of famous and not-so-famous artists, poets, writers, curators, and collectors.

— ca. 1952 —

Tanager Gallery opening

Photograph by Maurice Berezov (1902 – 89)

Tanager Gallery Records, 1952 – 79

— 1956 —

Gathering on the roof of the Tanager Gallery

Joellen Bard’s, Ruth Fortel’s, and Helen Thomas’s Exhibition Records of “Tenth Street Days: The Co-ops of the 50s,” 1953 – 77

The name Edith Gregor Halpert (1900–1970) figures prominently on the résumé of many of the most important American artists of the twentieth century. From the late 1920s through the 1960s, her Greenwich Village establishment, the Downtown Gallery, introduced or showcased such contemporary and future art stars as Stuart Davis, Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Jacob Lawrence, Charles Sheeler, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, and Ben Shahn. She was brilliant at using marketing and advertising to get her artists included in museum exhibitions and public collections. As one brochure stated, the Downtown Gallery had “no prejudice for any one school. Its selection is driven by quality—by what is enduring—not by what is in vogue.” By the mid-1960s, when this snapshot of an exultant Halpert was taken, exhibitions of modern American art from her collection were touring throughout the United States and Europe.

Una Hanbury (1904–90) was born in England. After World War II she and her family moved to the United States, first settling in Washington, D.C., and then moving to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where she maintained a studio until her death. She used a variety of materials for her work, but she is best known for bronze portrait busts. Hanbury must have had a way of charming famously difficult people. Though she would not move permanently to Santa Fe until 1970 and most likely had not previously known America’s most famous—and most notoriously reclusive—woman artist, the relaxed pose of the sitter and the casual attire of the sculptor depicted in this photo suggest an afternoon spent on the patio in easy conversation between two old friends. Whatever transpired, the result was a cast bronze portrait bust of Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986) now in the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Painter Honoré Sharrer (1927–2002), whose colorful, realistic paintings documented the daily experiences of ordinary working people, often used the camera to collect images for her paintings. Over many years she made hundreds of snapshots of people, animals, and architectural details and kept them in white envelopes labeled by subject, such as “Dogs,” “Teenage Boys,” and “Cars.” She often asked her subjects to strike particular poses or wear particular costumes, and many of these figures can be found reproduced exactly in her paintings. In later years, her husband, historian and University of Virginia Professor Perez Zagorin (1920–2009), was often Sharrer’s model in her makeshift photo studio.