A few publicity snapshots of three famous French artist brothers was what Walt Kuhn was after when he wrote in December 1912 to his friend Walter Pach, who was in Europe lining up artists for the Armory Show, scheduled to open in New York City early the next year. “A snapshot of the Duchamp-Villon brothers in their garden…will help me get a special article on them,” declared Kuhn. In January Pach arranged for the brothers to be photographed outside the adjoining studios of Jacques Villon (1875–1963) and Raymond Duchamp-Villon (1876–1918) in Puteaux, a Paris suburb adjacent to Neuilly-sur-Seine. Younger brother Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) took the train from Paris with Pach—the two would ultimately become close friends—and joined them. Following the February 18 opening of the exhibition, an article on all three brothers appeared in the April 6, 1913, issue of the New York Sun. It was good publicity for the traveling exhibition, but none of the exhibition’s organizers, not even Kuhn or Pach, anticipated the enormous succès de scandale created by Duchamp’s painting Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), which marked a decisive turning point in the development of American art.

— 1913 —

Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon, and Raymond Duchamp-Villon with dog Pipe in the garden of Villon’s studio, Puteaux, France

Walt Kuhn, Kuhn Family Papers and Armory Show Records, 1859 – 1978

Dorothy Dehner (1901–94) and David Smith (1906–65) met in 1926, shortly after each arrived in New York City (Smith from Washington, D.C., and Dehner from California) to live their lives as serious artists. Both attended the Art Students League of New York, the most prestigious school of art in the city. They married in 1928. Though they later divorced, Dehner happily recalled those first days together in an oral-history interview with the Archives of American Art at the end of her life: “He was terribly interested and very vital, and I remember, as a reaction from his spats-and-derby kind of dressing, he would go home and get into a pair of old slacks and some things he called romeos—they were great, flapping bedroom slippers with rubber sides, you know. And he would wear those to the [Art Students] League, and this made him distinctive.…He was terribly cute and very, very tall and skinny and quite a personality in the group there.”

William Glackens (1870–1938) was a painter and illustrator in Philadelphia and New York City, focusing on scenes of city life and street crowds. In 1908 he participated in the groundbreaking exhibition of the group of American artists known as The Eight at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City. His son, writer Ira Dimock Glackens (1907–90), was born in New York City and raised in his father’s world of artist friends and colleagues. He published two books about his father: William Glackens and the Ashcan Group: The Emergence of Realism in American Art (1957) and William Glackens and the Eight: The Artists Who Freed American Art (1984).

— 1937 —

William Glackens with his son, Ira, and their poodle in Stratford, Connecticut

Ira and William Glackens Papers, ca. 1900 – 89

When American art collector Chester Dale (1883–1962) visited artists Diego Rivera (1886–1957) and Frida Kahlo (1907–54) in Mexico sometime in the early 1940s, the two had just recently remarried and moved back into the Blue House, Frida’s family home in Coyoacán, a borough of Mexico City. Their marriages, both first and second, were passionate but difficult, and each carried on numerous extramarital affairs. By 1940 Rivera was an international celebrity in the art world, known for his monumental murals painted in Mexico and the United States. Kahlo was on the verge of great success and acclaim despite having suffered lifelong health problems and enduring numerous back surgeries and recoveries. Her bedroom became her studio, and her bed became the place from which she held court with lovers, husbands, and, on this day, an art collector eager to meet the (at least temporarily) happy couple. In 1945 Rivera completed a portrait of Dale, now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

— 1942 – 45 —

Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, Coyoacán, Mexico

Photograph by Chester Dale

Chester Dale Papers, 1897 – 1971

How this snapshot of Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) and his daughter Maya (b. 1935) came to rest among the papers of American abstract expressionist William Baziotes (1912–63) is—like the undocumented journeys of many snapshots—a bit of a mystery. Likely made in Paris, where Picasso remained during World War II, the image captures one of the best-known artists in the world standing as a proud papa with the nine-year-old Maya, the only child of his relationship with his mistress Marie-Thérèse Walter. Likely the photo first belonged to Samuel M. Kootz, who in 1946 organized a show of Picasso’s works at his Kootz Gallery in New York City. In the years following, Kootz and his wife, Jane, became quite close with Picasso, as Kootz did with some of the younger artists he represented, including Baziotes.

Marcel Breuer (1902–81) designed and built the house in this snapshot in collaboration with his mentor Walter Gropius (1883–1969) in the late 1930s. Gropius had recently accepted an appointment as chairman of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, and Breuer had followed to become a member of the Harvard faculty. With the mock seriousness that snapshots can display, the individuals—perhaps the homeowners themselves?—are arranged as modernist actors in an architectonic tableau. Their forms interrupt and possibly comment on the rectilinear rigor of the Bauhaus vocabulary developed by Gropius, Breuer, and their fellow modernists. If form follows function, then the function of these three carefully positioned figures is to remind us that space is made to be inhabited.

The scene is familiar. The party’s over; it’s late, but it’s still too early to go home. Gathered at what looks like an all-night cafe is an intriguing assemblage of modernists who seem to have enjoyed a festive, if tiring, evening together. Joining architect Marcel Breuer (fourth from right) is painter Mercedes Matter (1913–2001; far left), an original member of the American Abstract Artists organization, and the German architect Konrad Wachsmann (1901–80; third from left). Wachsmann immigrated to the United States in 1941 and collaborated with Walter Gropius on the Packaged House system, a kit that, the architects boasted, could be assembled in nine hours. On the far right, artist Alexander Calder expresses an irreverent comment on the night.

— ca. 1950 —

Marcel Breuer, Mercedes Matter, Konrad Wachsmann, Alexander Calder, and others

Marcel Breuer Papers, 1920 – 86

This lively cafe gathering boasts at least three famous mid-twentieth-century modern architects: Walter Gropius (second from left), Marcel Breuer (right foreground), and Le Corbusier (1887–1965; background, right, with head turned away). Because the back of the snapshot is stamped “unesco,” the gathering may have been connected to a Paris meeting of the United Nations agency. Le Corbusier had participated in the architectural development of the United Nations headquarters in New York City, which was then under construction. Former Bauhaus director Gropius, however, was excluded from the design team, along with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, because of his German origin; perhaps this gathering was meant to patch over that slight. Tellingly for the period, in this illustrious gathering of architects only one woman appears—at the front of the photo, obscured in a cloud of smoke.

Philip Pearlstein (b. 1924) was, like his friend Andy Warhol (1928–87), born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Both graduated from the Carnegie Institute of Technology. Though Pearlstein was older, having returned to school after a stint in the Army during World War II, the two were good friends and shared classes. Along with another student, Dorothy Cantor (b. 1928; later became Pearlstein’s wife), they rented a studio in a barn in the summer of 1947. Immediately after graduation the three moved to Manhattan, following in the footsteps of another Carnegie classmate, George Klauber, who had made connections with commercial illustration companies. It isn’t certain who made these student snapshots, but they are evidence of an often-present camera.

— ca. 1948 – 49 —

Arthur Elias, Philip Pearlstein, Andy Warhol, and Leonard Kessler in a painting studio at the Carnegie Institute of Technology

Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

— ca. 1948 —

Dorothy Cantor, Andy Warhol, and Philip Pearlstein on Carnegie Institute of Technology campus

Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

— ca. 1948 —

Andy Warhol on campus at the Carnegie Institute of Technology

Photograph by Philip Pearlstein Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

— ca. 1948 —

Philip Pearlstein on grass at the Carnegie Institute of Technology

Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

— ca. 1948 —

A party in a studio of the arts building at the Carnegie Institute of Technology

Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

Just a few weeks after their graduation from the Carnegie Institute of Technology in June 1949, Philip Pearlstein (who took these snapshots), his soon-to-be wife, Dorothy Cantor, and his young friend Andy Warhol moved to New York City. They rented an sixth-floor walk-up tenement apartment on St. Mark’s Place and Avenue A for the summer. Pearlstein’s snapshots suggest that an afternoon on the beach at Fire Island must have been a nice way to beat the city heat, though we might question Warhol’s beach attire of turtleneck and long pants. Taken before either artist was famous, before pop was hot, Pearlstein’s snapshots evoke a time of youthful fun and friendship in a world of artistic potential.

— ca. 1949 —

Andy Warhol in New York City

Photograph by Philip Pearlstein Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

— ca. 1949 —

Andy Warhol, Dorothy Cantor, Corinne Kessler, and Leah Cantor on Fire Island Beach, New York

Photograph by Philip Pearlstein Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

— ca. 1949 —

Andy Warhol and Corinne Kessler on Fire Island Beach, New York

Corinne Kessler (b. 1924 and known as Corky) was the sister of Andy Warhol’s Carnegie classmate Leonard Kessler (b. 1921). She was a modern dancer and a close friend of Warhol.

Photograph by Philip Pearlstein Philip Pearlstein Papers, 1949 – 2009

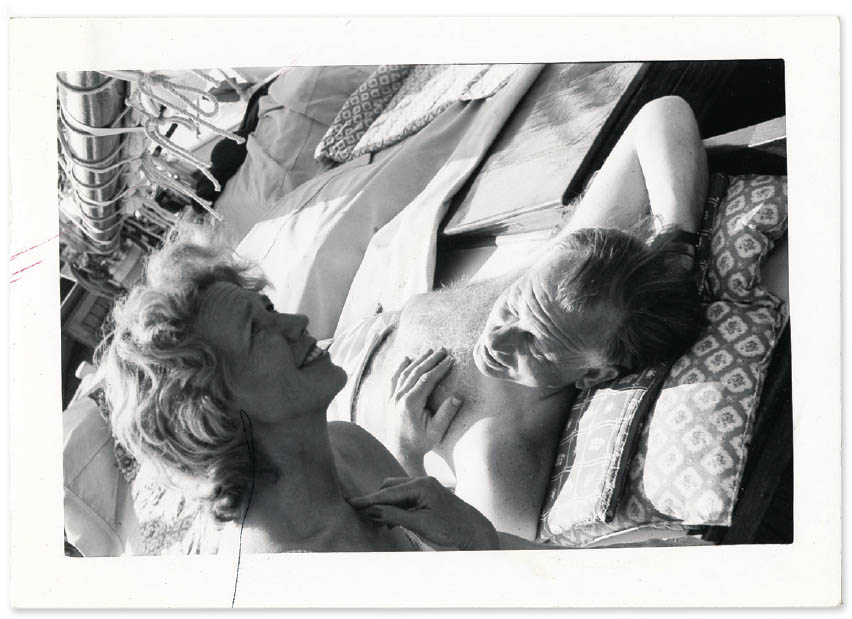

Though these pictures feature the casual style and off-centered framing shared by many everyday snapshots, the subjects of these photographs are anything but everyday sorts of people. Aline Bernstein Saarinen (1914–72) was one of the nation’s best-known critics of art and architecture when in 1954 she married her second husband, the noted Finnish-born architect Eero Saarinen (1910–61). They met when she traveled to Detroit to research a story about the new and acclaimed General Motors Technical Center and to interview the young man who was its architect. For the two, it was love at first sight. Though their time together was short (he died of a brain tumor seven years after they wed), they enjoyed a celebrated life, seemingly encapsulated by these snapshots of a sunny day of boating.

— ca. 1955 —

Aline and Eero Saarinen

Aline and Eero Saarinen Papers, 1906 – 77

The Little Paris Group was a Washington, D.C., organization of African American women—mostly teachers and government workers—who met regularly to exchange ideas and practice their art. The best-known members of the group, Loïs Mailou Jones (1905–98) and Alma Thomas (1891–1978), enjoyed long and successful careers as both teachers and artists. This image, perhaps taken after one of their regular sketching sessions, is stamped on the reverse “Kay-Dee Photo.” Possibly it was an outtake from a more formal group portrait session. Among those pictured are Barbara Buckner, Céline Tabary, Delilah Pierce, Elizabeth Williamson, Bruce Brown, Barbara Linger, Frank West, Don Roberts, Richard Dempsey, Russell Nesbit (model), Loïs Mailou Jones, Alma Thomas, and Desdemona Wade.

— 1958 —

Little Paris Group in Loïs Mailou Jones’s studio in Washington, D.C.

Photograph by Kay-Dee Photo Alma Thomas Papers, 1894 – 2000

Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–77) was known in Chicago, where she spent most of her life, as “queen of the bohemian artists.” A painter and illustrator who crafted a style out of both European surrealism and native realism, her work was inspired by Chicago jazz. Abercrombie was also a gifted improvisational pianist. She and her second husband, music critic Frank Sandiford, held Saturday-night parties and Sunday-afternoon jam sessions at their home with musician friends, including Sonny Rollins, Sarah Vaughan, and Charlie Parker. Dizzy Gillespie (1917–93), shown celebrating his birthday, performed at Abercrombie and Sandiford’s wedding.

— oct. 21, 1964 —

Gertrude Abercrombie with Dizzy Gillespie on his birthday

Gertrude Abercrombie Papers, 1880 – 1986

A note on the back of this snapshot indicates that it was made by art critic and Warhol chronicler David Bourdon (1934–98) on June 5, 1971. Even so, there is no way of knowing what was being celebrated by John, Yoko, and Andy (the posed familiarity of the photo suggests that everyone was on a first-name basis) on that early-summer evening at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York City. Whatever the occasion, the gallery would have been a likely place for these three art celebrities to meet up. Opened at 4 East Seventy-Seventh Street in 1957, it had by 1971 become the international epicenter for pop, minimalist, and conceptual art. Yoko Ono (b. 1933) was a well-known member of the avant-garde, most notably for being a member of the Dada-inspired Fluxus group. Warhol was already a member of the Castelli stable. And John Lennon (1940–80), besides being a Beatle, could claim art-world connections as Ono’s husband. Perhaps the photo marks the trio’s first visit to Castelli’s recently opened outpost in Manhattan’s downtown SoHo district. The snapshot itself suggests something of a performance. Is this a demonstration of pop music embracing pop art?