While it may not be a snapshot in the strictest sense, this image of Alexander Calder pretending to wrangle a herd of bulls on a Paris rooftop embraces the informal charm of the best snapshots. Calder lived in Paris between 1926 and 1933. During these years the young American created one of the most beloved works of modern art, a miniature circus that includes more than seventy small acrobats, tightrope walkers, and performing animals. Calder made each character by hand and designed many of the figures to move and interact with one another, sometimes staging performances for friends and family. Like his circus menagerie, these bulls were made to move; each appears to be equipped with a small wheel, all the better to evade the lasso of the artist.

— 1927 —

Alexander Calder wrangling toy bulls

Photograph by Lyman Studio Alexander Calder Papers, 1926 – 67

Today photobooths have almost disappeared in deference to digital selfies, but in the early decades of the twentieth century, photobooths could be found almost anywhere and were enjoyed by almost everyone. In train stations, subways, and department-store lobbies from New York to Chicago to Los Angeles, people waiting for trains or looking for a break from their everyday chores loved entering these magical spaces and pulling the curtain. Alone making faces or sharing looks or kisses with friends, the experience was for many both special and intimate. The small strip of images that result from the personal photo session seem almost like a bonus by the end of the intimate process.

In 1934 a special kind of photobooth appeared. Rather than producing strips of images, the Photomatic produced single images with a metal frame; each even came with a built-in stand for display. Like the inexpensive tintype images of an earlier photographic era, these portraits were made for exchange among friends, a form of personal communication and appreciation.

— ca. 1945 —

Gertrude Abercrombie kissing an unidentified individual

Gertrude Abercrombie Papers, 1880 – 1986

— ca. 1945 —

Gertrude Abercrombie and unidentified individual

Gertrude Abercrombie Papers, 1880 – 1986

— ca. 1945 —

Gertrude Abercrombie and unidentified individuals

Gertrude Abercrombie Papers, 1880 – 1986

— ca. 1945 —

Gertrude Abercrombie and unidentified individuals

Gertrude Abercrombie Papers, 1880 – 1986

Katharine Kuh (1904–94) and Ansel Adams (1902–84) met shortly after she opened her gallery in 1935—the first devoted to avant-garde art in Chicago. It was also the first Chicago gallery to show photography as art, including an exhibition of work by the young Adams. During the 1930s Adams made several trips from his home in San Francisco to New York, probably stopping over in Chicago. It is only speculation, but perhaps on his way to or from his 1936 solo exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery An American Place, Adams and Kuh took a moment in Union Station to say hello or good-bye and to make a record of their friendship.

— 1936 —

Katharine Kuh

Katharine Kuh Papers, 1875 – 1994

Why we keep some snapshots and lose others—and how the ones we keep merge into the accumulation of the papers of our lives—is often a mystery, even to ourselves. Sometimes a photograph is of someone we wish to remember or simply of someone we have been amazed to know. Sometimes a photograph is just so curious—such as this one of John Dos Passos (1896–1970) walking a dog—that we keep it for amusement alone. Painter Abraham Rattner, from whose papers this snapshot comes, and Dos Passos, one of the major novelists of the post–World War I Lost Generation, knew each other briefly in Paris during the 1930s. Rattner, himself a member of both the American and European avant-gardes, illustrated an article for Dos Passos in Verve magazine in 1931, just as the author’s major work, U.S.A. (a trilogy portraying America as two nations, one rich and privileged and one poor and powerless), was being published.

— 1940 —

John Dos Passos walking a dog in New York City

Abraham Rattner and Esther Gentle Papers, 1891 – 1986

Many snapshots are spontaneous performances of character. Southern California–based artist Helen Lundeberg (1908–99), in partnership with her husband, the artist and teacher Lorser Feitelson (1898–1978), is best known for founding in 1934 the movement they termed “subjective classicism,” later referred to by art historians as “post-surrealism.” Unlike European surrealists, who were concerned with analyzing their dreams, Lundeberg wanted to make art that revealed meaning, psychological or otherwise, through careful design. Even this snapshot (captured on a day’s outing in the countryside east of Los Angeles) suggests a deeper motive as the leaf and the shadow it casts represent a moment when body and mind were psychologically bridged.

— oct. 1943 —

Helen Lundeberg at Mount Baldy, San Bernardino County, California

Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg Papers, ca. 1890s – 2002

By the end his life, American painter, sculptor, printmaker, photographer, and performance artist Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008) had become one of the most celebrated artists of the twentieth century. Throughout his career he experimented with new materials and styles to challenge traditional art-making methods. It is tempting to read both pride and brashness in this backroom snapshot, likely taken during preparations for Rauschenberg’s first solo exhibition at the Leo Castelli Gallery, then on East Seventy-Seventh Street in New York City. The artist stands in front of one of the earliest and most ambitious of what he termed his “combine paintings.” Measuring more than nine feet wide, it combines oil paint, color reproductions, fabric, wood, and metal. Departing from his usual practice of leaving his work untitled, Rauschenberg gave this big, new painting a name: Charlene (1954).

Ellen Hulda Johnson (1910–82) was one of those rare combinations of dedicated scholar and popular professor. It was well known at Oberlin College, in Ohio, where Hulda taught for nearly thirty years, that if you wanted a seat in one of her lectures on the history of art, you had better show up early. She was a scholar of modern masters such as Cézanne and Picasso, but her most significant cultural contribution was her support of post-1945 American artists. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s she curated exhibitions and wrote many articles that helped to establish the careers of young artists involved in the pop art movement. Perhaps she brought a camera on her studio visits with artists such as Jasper Johns (b. 1930) as a form of biographical note taking for her contemporary art history, perhaps as a form of personal remembrance, or perhaps to document the nature of artistic temperament for her eager students.

— 1963 —

Jasper Johns in his New York studio

Photograph by Ellen Hulda Johnson

Ellen Hulda Johnson Papers, 1939 – 80

It is hard to believe that this brooding artist is Jim Dine (b. 1935), one of the most witty and imaginative members of the pop art generation. Along with artists Claes Oldenburg, Red Grooms, and others, Dine staged many of the first performances known as Happenings. His paintings from that period, which included tools and pieces of clothing collaged onto the canvas, were an equally irreverent break with tradition. At the time that art historian and early pop art supporter Ellen Hulda Johnson took this snapshot, Dine was fast becoming a recognized artist. He would soon have solo shows at the prestigious Sidney Janis Gallery in New York City.

— mar. 1963 —

Jim Dine in his New York studio

Photograph by Ellen Hulda Johnson

Ellen Hulda Johnson Papers, 1939 – 80

Painter Kenneth Noland (1924–2010) is shown inspecting one of his paintings in his studio in Shaftsbury, Vermont. Noland, who pioneered the use of shaped canvases, was one of the best-known American color-field painters. The 1960s were productive years for him: not only was he a featured artist in the American pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 1964, but he was also included in the exhibition Post-Painterly Abstraction, curated by Clement Greenberg in the same year, which traveled the country and helped to establish color-field painting as an important new movement in contemporary art. The decade also marked the beginning of his long association with the photographer of this studio snapshot, art dealer André Emmerich (1924–2007), whose important New York City gallery mounted almost annual exhibitions of Noland’s work.

Kenneth Noland in his studio in Shaftsbury, Vermont

Photograph by André Emmerich

André Emmerich Gallery Records and André Emmerich Papers, 1929 – 2008

For much of the second half of the twentieth century, André Emmerich presided over one of the world’s most influential art galleries. Born in Europe and educated in America, he initially thought he would be a writer. Instead, with sophisticated aplomb he became a gallery owner whose exhibitions were lauded in newspapers as much for the clean, white space of the gallery as for the art. A strong advocate of abstract sculpture, he moved his New York gallery twice to accommodate larger work, such as these pieces by Anthony Caro. This snapshot was taken on a visit to Caro’s backyard studio in Milan, Italy.

In the spring and summer of 1982, David Hockney (b. 1937), an English painter who was well known on both sides of the Atlantic and both coasts of the United States for his draftsmanship, introduced a radically new body of work. His exhibition Drawing with a Camera took place on the West Coast at the L. A. Louver gallery and on the East Coast at the André Emmerich Gallery in New York City. These exhibitions consisted of portraits assembled from sx-70 Polaroid photographs arranged in rectangular grids, each of which showed only a detail of the subject. One of these “camera drawings” is leaning against the wall at the right in this snapshot. While Hockney had used photographs as inspiration for and references in earlier paintings (and would continue to do so), the Polaroid collages mark the artist’s growing interest in photographs as works of art in themselves.

— apr. 1982 —

David Hockney at his studio in Los Angeles

Photograph by André Emmerich

André Emmerich Gallery Records and André Emmerich Papers, 1929 – 2008

Colin de Land (1955–2003) and Pat Hearn (1955–2000) met when each opened a gallery in New York City’s East Village in the mid-1980s. Hearn’s eponymous gallery on Ninth Street and Avenue D showed a wide range of contemporary painting, installation, photography, and video. De Land’s first gallery, Vox Populi, was around the corner. They married in 1999. Together they organized the Gramercy International Contemporary Art Fair, held in various cities, which was a precursor of The Armory Show in New York City, now an annual art-world event. Hearn and de Land used photography in their lives away from the galleries for the express purpose of producing personal documents. The enormous volume of images now in the Archives of American Art describes an almost compulsive desire to record as many minutes of life as possible. These include candid snapshots of exhibition openings, art fairs, vacations, social gatherings, and New York City street scenes. Parties at their apartment were noteworthy. Christmas was especially celebrated. Continuous sequences of snapshots combine unrehearsed intimacy with an artfulness learned from the picture world in which they lived. Hearn died of liver cancer in August 2000. De Land died three years later.

— dec. 1994 —

Room at the Chateau Marmont during the Gramercy International Contemporary Art Fair in New York City

One of the photos propped up on top of the minifridge is a work by Art Club 2000, Untitled (Cooper Union, Puzzle Party 1, 1994).

Colin de Land Collection, 1968 – 2008

— dec. 28, 1995 —

Christmas at the home of Pat Hearn and Colin de Land

Colin de Land Collection, 1968 – 2008

— ca. 2000 —

Interior of a taxicab

Colin de Land Collection, 1968 – 2008

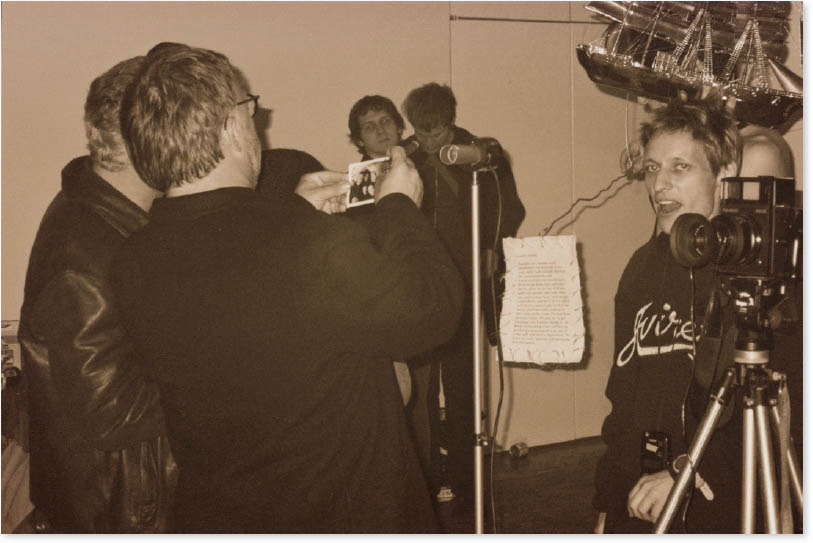

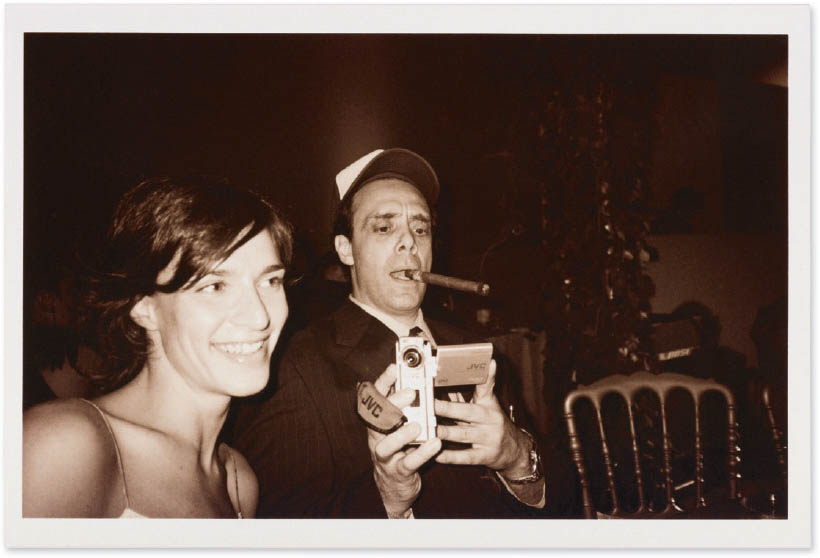

Colin de Land’s American Fine Arts, Co. on Wooster Street in SoHo, like his earlier gallery, showed a wide range of cutting-edge art, from postmodernist critiques and video installations to new abstract painting. It also served as something of a community center for the late twentieth-century New York avant-garde. Always provocative, de Land functioned as gallery director, party organizer, and art-world entertainer. Cameras loaded with film, including Polaroid instant cameras, were always on hand in the gallery; anyone and everyone were invited to use them. In this way, a seemingly continuous stream of photographs as life was produced. The pictures document in an appropriately nontraditional way the everydayness of de Land’s gallery life: installations, the flow of gallerygoers, backroom hanging out, and, above all, the parties.

— ca. 2000 —

Patterson Beckwith and others at a party

Colin de Land Collection, 1968 – 2008

— 2000 —

Colin de Land and an unidentified woman at a party

Colin de Land Collection, 1968 – 2008