2

People

In 1798, at opposite ends of Europe, two major treatises on population were published. The more authoritative of the two was written by Joseph von Sonnenfels, the leading political scientist of the Austrian Enlightenment. In his Manual of the domestic administration of states, with reference to the conditions and concepts of our age, he summed up the conventional wisdom, namely that a large and growing population was a Good Thing. Indeed, he went so far as to assert that demographic increase should be made ‘the chief principle of political science’, for the good reason that it promoted the two chief ends of civil society: material comfort and physical security. The greater the population, Sonnenfels argued, the greater the country’s agricultural productivity and the greater the capacity to resist both foreign enemies and domestic dissidents. To clinch it, he pointed out that the more people there were to contribute to the expenses of the state, the less the tax burden on the individual would have to be. This common-sense approach was underpinned by the belief that the population of the world had been declining since classical times. It was a conviction Sonnenfels shared with most of his contemporaries, including Voltaire and Montesquieu. The latter observed gloomily: ‘if this decline in population does not cease, in a thousand years the world will be a desert’.

A very different view was expressed in the same year by the young Englishscholar Thomas Malthus, in An Essay on the Principle of Population as it affects the Future Improvement of Society, At thirty-two, he was almost exactly half Sonnenfels’ age, but his vision of the future was at least twice as bleak. His chief concern was to counter the belief in the perfectibility of the human race advanced by progressives such as William Godwin and the Marquis de Condorcet. Malthus proceeded from two premises: ‘that food is necessary to the existence of man’ and ‘that the passion between the sexes is necessary, and will remain nearly in its present state’. These two natural laws were not of equal force, however, for ‘the power of population is indefinitely greater than the power in the earth to produce subsistence for man’. A man and a woman could give life to several children, each of whom could do the same. Consequently, demographic growth proceeded in a geometrical progression, whereas agriculture could only expand arithmetically. In other words, the number of people generated by the sequence 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128 could not be sustained by resources generated by the sequence 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. The necessary result was that, sooner or later, any expansion of population would be halted naturally when it banged its head against the ceiling imposed by this discrepancy. A combination of misery and ‘vice’ (by which the Rev. Malthus meant contraception) would soon redress the balance.

In the long run, both men were to be proved wrong, but in 1798 either position seemed credible. During Sonnenfels’ lifetime (he had been born in 1732), both the power and prosperity of his country had increased hand-in-hand with its population. One of the four Emperors he served, Joseph II, stated as a central axiom: ‘I consider that the principal object of my policy, and the one to which all political, financial and even military authorities should devote their attention, is population, that is to say the preservation and increase of the number of subjects. It is from the greatest possible number of subjects that all the advantages of the state derive.’ Yet all over Europe, periodic subsistence crises lent support to Malthus’ gloomy forecast, not least the harvest failure which arguably precipitated the French Revolution. If Malthus had lived a little longer (he died in 1834), he might well have found grim satisfaction in observing the misery of the ‘hungry forties’, especially the potato famine and ensuing mass emigration which reduced Ireland’s population from 8,400,000 to 6,600,000 in just five years. As this ambivalence suggests, in this respect the end of the eighteenth century was on the cusp between old and new. As we shall see, demographically the period 1648–1815 was in many respects more like the fifteenth than the twentieth century, although it also had many modern characteristics.

NUMBERS

It is not difficult to appreciate why, of all the branches of historical scholarship, demography should be among the most contentious. On the one hand, its practitioners have the opportunity to crunch numbers down to several decimal points, thus giving a spurious impression of precision. On the other hand, in any period before the censuses of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, evidence is so fragmentary that words such as ‘estimate’, or even ‘guess’, seem too precise to describe the results. The choice seems to be between bold statements about national totals and the microscopic ‘reconstitution’ of small communities, on whose microscopic foundations great airy structures are then erected. Especially in regions with poor communications, negligible literacy rates and little or no regular administration, such as Hungary following the Habsburg reconquista of the late seventeenth century, virtually nothing can be known about the level of population. However, demographic developments are so fundamental to an understanding of this, or any other, historical period that an attempt must be made to construct some sort of structure, although the straw and even most of the bricks are lacking.

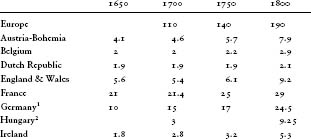

A good place to start is a summary of the best population estimates for a number of European countries between the middle of the seventeenth century and the end of the eighteenth (see Table 2).

Table 2. Population of European countries 1650–1800(in millions)

All of these statistics are approximate but some are more approximate than others. The figure for England in 1650, for example, can be set down with far greater confidence than that for Russia, which may be completely wrong. To give national figures is also somewhat misleading, as there were wide regional variations within any given country. For example, in Spain the population of provinces on the periphery, notably Catalonia, Valencia and Galicia, increased much more rapidly than in the Castilian centre. In France growth was strongest in Hainaut, Franche-Comté and Berry, moderate in the Parisian basin, Brittany, the Massif Central, the south-west and the Midi, and weakest in Normandy. In Germany, not surprisingly, much higher rates were recorded by the thinly populated east than by the relatively densely populated west–indeed, as we shall see, there was a significant amount of internal migration.

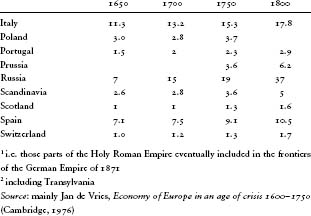

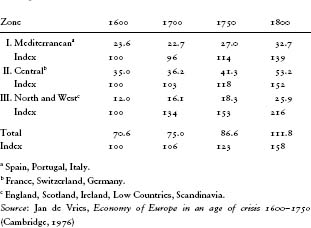

Table 3. Population of Europe (in millions)

Even after every qualification has been carefully noted, a general picture can be identified. Chronologically, this presents a sequence of stagnation or slow growth (1650–1700), followed by a general if modest increase (1700–50) and then by a more rapid expansion (1750–1800). But its true significance emerges only when it is placed in a much wider time frame. Following the catastrophic population losses caused by the Black Death in the middle of the fourteenth century, recovery began in the late fifteenth and continued throughout the sixteenth. But around 1600, the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse returned with a vengeance to many parts of Europe, bringing war, plague and famine with devastating demographic consequences. The great plague which struck Castile in 1599–1600, for example, was only the first of many such visitations which reduced the population of the region by a quarter by 1650. Only England and the Dutch Republic managed to avoid the general decline of the first half of the seventeenth century. So the developments of 1650–1800 represent both a recovery and a resumption of growth. However, much more important than what preceded our period, was what followed it. Despite the warnings of Malthus, the expansion of the second half of the eighteenth century was not checked by inelastic subsistence. On the contrary, Europe’s population went on growing throughout the nineteenth century at an ever-accelerating rate.

Geographically, as Table 2 reveals, there was a shift in the demographic balance of Europe away from the Mediterranean to the north-west. This becomes clearer if the individual countries are grouped by region (Table 3).

The eminent Dutch economic historian Jan de Vries, who compiled Table 3, added laconically that he would have added a fourth region–Eastern Europe, embracing Poland and Russia–but there was insufficient data.

The shift in Europe’s demographic centre of gravity was momentous. Late medieval and Renaissance Europe had been dominated by the Mediterranean. In manufacturing, trade and banking, its cities had been pre-eminent; in culture, the Italian city-states had created a civilization which bore comparison with classical Greece; in politics, the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs had created an empire on which the sun never set. Yet by the eighteenth century, northerners were coming south as if to a museum, their admiration for its past exceeded only by their contempt for its present. As an English visitor put it in 1778, Rome had once been ‘inhabited by a nation of heroes and patriots, but was now in the hands of the most effeminate and most superstitious people in the universe’. As we shall see, the relative demographic decline of the region was both symptom and cause of a wider set of problems.

MARRIAGE AND FERTILITY

One possible explanation for the secular increase in Europe’s population was a rise in fertility as a result of women getting married younger. A drop in the average age of marriage by just five or six years could mean a 50-per-cent increase in the number of children born. Indeed, Tony Wrigley has argued that it was just this sort of reduction which accounts for three-quarters of the growth of population in England between 1750 and 1800. It was certainly very easy to get married in England, with an age of consent of fourteen for boys and twelve for girls. Nor was there any need for a church service–an exchange of oaths in the presence of witnesses, or even just an exchange of statements of intent to marry, followed by sexual intercourse, was regarded as sufficient. Yet here, as elsewhere in northern and western Europe, marriage was delayed until long after sexual maturity, the average age lying within a range of 241/2 to 261/2 years. Although there was certainly a reduction in England during the latter part of the eighteenth century, Wrigley’s critics have argued that it may have been offset by women calling an earlier halt to childbearing.

The long delay in contracting marriage–only one English bride in eight was a teenager when she first married–was not offset by any compensating extra-marital fertility. By the standards of the twenty-first century, the illegitimacy rates were amazingly low: in most European countries the rate rarely reached 5 per cent and was often below 2 per cent, as it was in England. (In the United Kingdom today the rate is above 30 per cent). In France it was barely 1 per cent in the countryside and only 4–5 per cent in Paris. However, there was an undoubted move upwards during the course of the eighteenth century. By 1789 the illegitimacy rate had reached 4 per cent in French towns with populations of more than 4,000, 12–17 per cent in full-blown cities and 20 per cent in Paris. In Germany in the same period there was a similar increase from 2.5 to 11.9 per cent. However, the modest increase in fertility these figures represented could have had only a small impact overall, even if all of the children born out of wedlock had survived to adulthood. In the event, as we shall see, they were especially prone to dying in infancy.

In those parts of Europe where a strong degree of social control was exercised by churches, guilds or seigneurs, the decision to delay marriage was often imposed from above. In northern, western and central Europe, however, it was usually a voluntary response to economic circumstances. There appears to have been a strong feeling that marriage should not be contracted until the couple was in a position to set up an independent household. It was also here that the highest numbers of women who never married were to be found. In north-western Europe 10–15 per cent and in some places even 25 per cent of women remained celibate, making this a more important check on population growth than the late age of marriage. In the east and the south, on the other hand, the rate was much lower and there was also less reluctance to accept a subordinate position in an extended household, with a corresponding reduction in the age of marriage. Everywhere dowries posed a problem, especially for fathers blessed with an excess of daughters, such as Mr Bennet of Pride and Prejudice. The English social historian, the late Roy Porter, did not believe that Sir William Temple (1628–99) was being unduly cynical when he wrote ‘our marriages are made, just like other common bargains and sales, by the mere consideration of interest or gain, without any love or esteem’. Certainly the newspaper announcements Porter cited in support of this generalization have a flavour all the more hard-nosed for their clerical origin:

MARRIAGES

Married, the Lord Bishop of St Asaph to Miss Orrell, with £30,000.

Married, the Rev. Mr Roger Waind, of York, about twenty six years of age, to a Lincolnshire lady, upward of eighty, with whom he is to have £8,000 in money, £300 and a coach-and-four during life only.

Disqualified by celibacy from clerical enterprise of this kind, the Catholic Church made a modest demographic contribution by establishing institutions such as the Italian monti di maritaggio, to provide dowries for impecunious girls. The general determination to guard against impoverishment–‘no land, no marriage’–condemned large numbers of males and females to celibacy if not chastity. In Catholic Europe, the most common asylum was the monastery or the nunnery. Unmarried girls obliged to become brides of Christ rather than men were also required to provide a dowry for their nunnery, but the sum was appreciably less. It is not often appreciated just how thriving were the monastic establishments of eighteenth-century Europe. Around the middle of the eighteenth century there were at least 15,000 monasteries for men and 10,000 numeries for women, with a total complement of c.250,000. Voltaire summarized their contribution to society with the dismissive comment: ‘they sing, they eat, they digest’. As with most of Voltaire’s anti-clerical jibes, this was grossly unfair, as many monks and nuns worked hard in a wide variety of demanding roles. But one thing they did not do was procreate.

They did not procreate, except on very rare occasions, although they may well have engaged in clandestine sexual activity. Indeed, if the increasingly scurrilous anti-clerical literature of the eighteenth century is to be believed, they engaged in little else. Mutatis mutandis, married couples were positively encouraged, if not required, to engage in sexual activity, but did not always procreate. Contraception is a branch of demography especially clouded by lack of direct evidence, but it is also one in which there is an unusual degree of consensus. Whether writing about Colyton, Geneva, Besançon or Rouen, there is general agreement that family planning was widely practised, especially among the elites, and on an increasing scale. In Rouen, for example, fertility rates fell consistently from 1642 to 1792, with a brief interlude in the middle of the eighteenth century. Births per family halved from eight in 1670 to four in 1800, as women stopped having babies earlier, or even stopped having them altogether (the proportion of the wholly childless doubled from 5 per cent to 10 per cent during the same period).

As contraception in any shape or form was condemned as vigorously by Protestants as by Catholics, very little evidence has been left of the techniques employed. There were plenty of herbal and/or magical recipes on offer, but it may be doubted whether they were very effective. More reliable, but by no means infallible, was the condom. This was allegedly the invention of a Dr Condom, seeking to limit Charles II’s brood of illegitimate children, although the word is more likely to derive from the Latin condus for receptacle. Until the discovery of the vulcanization of rubber in the 1830s, the only materials available were cloth (too porous) or animal intestines (too insensitive). Although condoms were certainly in use, by James Boswell for example, they appear to have been used for the avoidance of disease rather than contraception. In the words of an anonymous English poet of 1744:

Let not the Joy she proffers be Essay’d,

Without the well-try’d Cundum’s friendly Aid.

Indicative of the low esteem in which the condom was held was the attempt to portray it as some other country’s invention, the English calling them ‘French letters’ and the French calling them ‘English overcoats’. Less cumbersome but more fallible was a sponge inserted in the vagina, allied with post-coital use of a syringe or bidet for washing out any remaining sperm. Literary evidence suggests that this combination was especially favoured in France, where the ubiquitous bidet remained a source of misunderstanding and mirth for foreign visitors until relatively recently.

The only secure form of contraception was abstinence, or rather abstinence from ejaculation inside the vagina. Demographic historians find it easy to agree that coitus interruptus was both the most popular and most effective technique employed. Unfortunately, it raised intractable theological issues. Was it acceptable to engage in copulation solely for the purpose of enjoyment, without the intention of procreation? Was not premature withdrawal of the male member disturbingly close to the sin of Onan (‘And Onan knew that the seed should not be his; and it came to pass, when he went in unto his brother’s wife, that he spilled it on the ground, lest that he should give seed to his brother. And the thing which he did displeased the Lord: wherefore he slew him also.’ Genesis 38: 9–10)? How should one interpret, for example, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer (1662), which states that marriage was ordained by God for three reasons: ‘for the procreation of children’, ‘for a remedy against sin, and to avoid fornication; that such persons as have not the gift of continency might marry’, and ‘for the mutual society, help, and comfort, that the one ought to have of the other, both in prosperity and adversity’? That coitus interruptus was widespread, despite these problems, was demonstrated not least by the numerous–and very popular–pamphlets which inveighed against it. The author of Onania; or the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution, and all its Frightful Consequences, in both Sexes, consider’d, which went through twenty editions between 1710 and 1760, was in no doubt about its ethical status: it was absolutely unacceptable. When a reader wrote in to argue that he and his wife could not afford to support any more children and therefore his conscience was clear, he was told bluntly that he was committing ‘an abominable sin’. From the opposite end of the theological spectrum, no one summed up better the repertoire of birth control techniques available to an early modern couple than the marquis de Sade, including his own favoured solution. In Philosophy in the boudoir (1795) he has his two arch-rakes explain to the ingénue how to avoid pregnancy:

MADAME DE SAINT-ANGE A girl risks having a child only in proportion to the frequency with which she permits the man to invade her cunt. Let her scrupulously avoid this manner of tasting delight; in its stead, let her offer indiscriminately her hand, her mouth, her breasts, or her arse…

DOLMANCÉ…To cheat propagation of its rights and to contradict what fools call the laws of Nature, is truly most charming. The thighs, the armpits also sometimes offer him retreats where his seed may be spilled without risk of pregnancy.

MADAME DE SAINT-ANGE Some women insert sponges into the vagina’s interior; these, intercepting the sperm, prevent it from springing into the vessel where generation occurs. Others oblige their lovers to make use of a little sack of Venetian skin, in the vernacular called a condom, which the semen fills and where it is prevented from flowing farther. But of all the possibilities, that presented by the arse is without doubt the most delicious.

MORTALITY–FAMINE

Despite the marquis de Sade’s wishful thinking, sodomy remained very much a minority taste, not least because it was punished so severely when detected (see below, pp. 000–0). Certainly it does not appear to have had any discernible impact on the fertility figures of old regime Europe. On the other hand, the cumulative effect of birth control techniques certainly depressed rather than elevated Europe’s population. The trend towards an earlier age of marriage in some regions certainly pointed in the other direction but not sufficiently to explain the rise. Demographers therefore conclude that explanations based on fertility are inadequate. Instead, they concentrate on a decline in mortality, especially on the diminution, if not disappearance, of the three great killers of the seventeenth century: famine, war and plague.

Perhaps no aspect of everyday life in the twenty-first century separates us more sharply from the early modern period than food prices. Although so taken for granted as to be invisible, the stability and low level of basic foodstuff prices are among the more agreeable characteristics of the modern world. Every now and again, there is a flurry of press interest if, say, adverse meteorological conditions in Brazil sends the price of instant coffee up by more than a few pence but, generally speaking, the cost of a regular shopping expedition is predictable from one year to the next. Moreover, for the great majority, the proportion of a salary spent on food is low and getting lower. This is a necessary consequence of a global division of labour, which in turn derives from quick and cheap transport. But for the early modern household, by far the greatest single item of expenditure was food, and by far the greatest source of anxiety was fear that the harvest would fail. Before steam power opened up the limitless productivity of the North American plains, most food had to be grown locally. As we have seen in chapter 1, in the age of the quadruped, so difficult was it to transport the staple crop–grain–that any profit disappeared before even a few miles had been covered.

This problem was compounded by a dangerous over-reliance on cereals and thus on the weather. The latter presented two kind of problem in the period 1648–1815. The first was macroscopic: there is a good deal of evidence that the late seventeenth century formed part of a much longer ‘new ice age’ which had begun a century or so earlier. Taking the period 1920–60 as a basis for comparison, it can be shown that average mean temperatures were 0.9°C lower during the second half of the seventeenth century and 1.5°C lower during the 1690s. That may not sound very much, but it appears to have had a seriously depressing effect on agricultural productivity. The second meteorological problem was short-term, namely the devastating effect that a wet winter or spring, or even a sudden hailstorm at harvest-time, could have on yields. It is worth remembering that early modern cultivators did not select their seed but simply kept back part of the previous crop; that the varieties they used had not been adapted to make the most of their soil and growing conditions; that even in a good year the yield might be as low as four or five grains to each one retained; that they had no mechanical equipment to harvest, thresh or dry; and that storage facilities were usually anything but watertight.

So, especially in the lands of the north, west and centre, peasant-producers knew that it was not a question of ‘if’ but ‘when’ a year of dearth would come. When it did, the signs would already be there by spring, in the form of stunted growth and rotting roots. With rumours of impending crop failure spreading, prices would begin to rise, as the well-off hurried to stock their larders. Those with grain to sell–the noble and ecclesiastical landowners, the grain merchants and the richer tenant-farmers–would then keep back their stocks from market, waiting for prices to reach their cyclical peak. Even in a normal year, late spring and early summer formed a difficult time in the calendar of consumers (and their governments), for it was then that the grain stocks of the previous year were beginning to run out but the new harvest had not yet been gathered in. This window of anxiety was known in France as la soudure (‘the gap’). If the current harvest then really did prove to be disappointing, prices could start to go through the roof. And that was not the end of it. Most peasants did not cultivate enough land to allow them to be self-sufficient, but needed to enter the market as purchasers to make up the shortfall. To raise the necessary cash, they relied on labouring or some kind of manufacturing activity such as weaving or spinning. However, just when higher grain prices made this supplementary income all the more necessary, demand for manufactured items collapsed, because consumers were now having to spend so much more of their income on food.

By the autumn of a year of harvest-failure, a large and growing number of people would find themselves excluded from the market. To survive, they resorted to inferior forms of food, to consuming their seed corn, to begging, to crime, to whatever. The lucky, the young, the healthy and the enterprising might get through the winter, but woe betide them if the following year’s harvest also proved to be a failure. In May 1693 a minor official in the French bishopric of Beauvais noted that the price of corn had gone up sharply, causing acute hardship. Eleven months later, he wrote again, this time with a harrowing description of

an infinite number of poor souls, weak from hunger and wretchedness and dying from want and lack of bread in streets and squares, in the towns and countryside because, having no work or occupation, they lack the money to buy bread…Seeking to prolong their lives a little and somewhat to appease their hunger, these poor folk for the most part, lacking bread, eat such unclean things as cats and flesh of horses flayed and cast on to dung heaps, the blood which flows when cows and oxen are slaughtered and the offal and lights and such which cooks throw into the streets…Other poor wretches eat roots and herbs which they boil in water, nettles and weeds of that kind…Yet others will grub up the beans and seed corn which were sown in the spring…and all this breeds corruption in the bodies of men and divers mortal and infectious maladies, such as malignant fevers…which assail even wealthy and well-provided persons.

The demographic effects of this sequence are not difficult to imagine, for one need only translate the sickeningly familiar images of present-day famines in the Horn of Africa to a European setting. Most obviously, marriage and birth rates plunged, while mortality–and especially infant mortality–rates soared. It has been estimated that during the terrible mortalité of 1692–4, 2,800,000 people, or 15 per cent of the total population of France, perished. The 1690s proved to be particularly destructive all over western, northern, central and eastern Europe. In Finland the famine of 1696–7 carried off at least a quarter and perhaps as much as a third of the population. In Scotland, a poor harvest in 1695 was followed by severe failure in 1696, a modest improvement in 1697 but general failure in 1698. In the worst affected counties, such as Aberdeenshire, the mortality rate reached 20 per cent. As Sir Robert Sibbald observed: ‘Everyone may see Death in the Face of the Poor.’ Only England and the Dutch Republic escaped the holocaust, perhaps because their agricultural systems were better-balanced but more probably because their better water communications allowed both better circulation of surpluses and supplies from outside to be brought in.

There were bad harvests right across Europe in 1660–63, 1675–9, 1693–4 and 1708–9, together with plenty more localized famines in between. But then the situation began to improve. After 1709 there were no more famines in France, although there were plenty of years of acute shortages, not least in 1788–9. There were widespread subsistence crises in 1741–2, in the early 1770s and the late 1780s. Every now and again there would be a local outbreak of horrors of the late-seventeenth-century variety, as there was in Sicily in 1763 when the harvest failed, tens of thousands starved to death and social order broke down. For the reasons discussed earlier, food shortages could not be eliminated from Europe until improvements in communication opened up the grain-growing plains of the New World, but, even so, the eighteenth century marked a distinct improvement on what had gone before. As we shall see in a later chapter, part of the explanation is to be found in improved agricultural methods and part in more effective government action. It is also likely that a gradual improvement in meteorological conditions raised production levels. In any event, one reason for the striking difference between the demographic histories of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries must lie in the reduction in the number and severity of famines.

MORTALITY–WARS

The first fifty years of the seventeenth century had witnessed some of the most terrible and most sustained blood-letting in human history. At home, faction-fighting turned into civil war; abroad, few parts of Europe were not affected by the epochal struggle between Habsburgs and Bourbons. The result was demographic catastrophe. In 1652, a report to the ecclesiastical authorities on the condition of the region around Paris affected by the ‘Frondes’, as the civil war of 1648–53 was known, recorded ‘villages and hamlets deserted and bereft of clergy, streets infected by stinking carrion and dead bodies lying exposed, houses without doors or windows, everything reduced to cesspools and stables, and above all the sick and dying, with no bread, meat, medicine, fire, beds, linen or covering, and no priest, doctor, surgeon or anyone to comfort them’. Yet these inhabitants of the Parisian bassin were the lucky ones, for at least the conflict which engulfed them was of relatively short duration. To the east, by that time, there was a whole generation which had grown up knowing nothing but the horrors of war. During the Thirty Years War, which began with the defenestration at Prague on 23 May 1618, armies rampaged across central Europe again and again. Only the Alpine regions and one or two favoured parts of the north were spared.

Contemporaries were in no doubt that this conflict was especially brutal, even by the terrifying standards of early modern warfare. Both literature, for example Grimmelshausen’s Simplicissimus, and the visual arts, for example Jacques Callot’s Les Misères et les Malheurs de la Guerre, convey harrowing evidence of the looting, rape and murder inflicted by the soldiers. Subsequent scholars have argued long and hard about the quantitative damage inflicted. German nationalist historians of the nineteenth century were only too anxious to believe that foreigners had plunged their country back into a dark age, from which only now–thanks to Prussia–it was at last emerging. That sort of narrative in turn provoked a strong reaction in the later twentieth century, when all kinds of qualifications to the ‘doom and gloom’ scenario were advanced. However, the consensus still seems to favour the figures first produced by Günther Franz in 1943 which showed that the urban population declined by a quarter and rural population by a third. Those figures, however, are national averages; depending on the region, they could range from zero losses to well over 50 per cent.

The recovery of Germany’s population after the end of the war was clearly in part just that–recovery. Once the armies had gone away, the natural buoyancy could return. Personifying the amazing virility and fecundity of the survivors was Hans Bosshardt, who got married for the fourth time at the age of eighty, his bride being his twenty-year-old goddaughter. He had three children by her, the youngest being born in the same year that its sixty-six-year-old half-brother died. The energetic Hans eventually died aged 100 whereupon his widow kept up the good work by soon remarrying. Unfortunately, it turned out that the war had not gone away for good. It returned with a vengeance in the 1670s, when Louis XIV sought to expand France’s frontiers in the east. The Palatinate had barely recovered from the Thirty Years War when it was laid waste by the armies of General Turenne in 1674. The Elector Palatine, Karl Ludwig, made Louis XIV personally responsible for the destruction of thirty years of rétablissement, but that did not prevent the French armies coming again and again in the 1680s. In 1689 the systematic, officially authorized destruction of Heidelberg, Mannheim, Worms, Speyer and many other towns in the region represented a new and ominous departure in the history of warfare. In 1693 the French returned, this time to burn Heidelberg to the ground. Far from being apologetic, Louis XIV had a medal struck bearing the boast ‘Heidelberg deleta’.

It was not only the hapless Germans who suffered repeated demographic setbacks in the second half of the seventeenth century. In the south-east, the new attempt by the Ottoman Turks to take control of the Danube valley and the ensuing Austrian reconquista of Hungary, left huge tracts of territory virtually uninhabited. In the north-east, the long struggle between the Scandinavian countries, Poland and Russia for domination of the Baltic region also decimated the population periodically. In 1658, for example, Polish armies moved into Denmark to drive out the Swedes. What followed was a fine illustration of the old adage that, for civilians, allies were to be feared just as much as enemies. It was reported from southern Jutland: ‘The Poles drove us from house and home, treated us brutally, and took away all we had, cattle and corn and everything we possessed, so that many were doomed to die of hunger; and so in the herred [district] of Malt there are only two, three or four persons left alive in every parish, and many corpses are eaten up in the houses by dogs.’ The parish priest of the town of Malt confirmed this grim news, adding that with but few exceptions all his parishioners were dead and their houses burnt. Mortality rates of up to 90 per cent were reported. The herred court was told: ‘in God’s truth [it is] well known that before this dismal, wretched war and raging pestilence came upon us, the parish and parishioners of Rev. Christian Jensen were in full vigour…and there were then in the parish of Føvling forty-five farms and seven homesteads, of which no more than six farms and three homesteads now remain…The other farms are quite deserted.’

So war had not lost its teeth. Yet taking a very long view of the period 1648–1815, or at least 1648–1792, it can be seen that it did gradually lose some of its destructive force. It was not that wars became less frequent: on the contrary, there was a major war between the European powers in every decade of the eighteenth century except perhaps the 1720s. Rather it was the case that armies were now better disciplined and better provisioned. For reasons to be discussed later, one state after another moved to establish control over their armed forces. War was still a terrible affliction for anyone unfortunate enough to get in its way, but conflicts did become shorter in duration and more limited in geographical scope. It was Frederick the Great’s declared ambition to isolate warfare from civilians to the extent that they would be unware that it was underway. Of course he failed, indeed he himself claimed that the Seven Years War had been as catastrophic from a demographic point of view for Prussia as the Thirty Years War. However, there was no return to the anarchy of the first half of the seventeenth century. It is impossible to imagine, say, one of Wallenstein’s officers making the following observation by a Prussian subaltern in the Seven Years War:

We were never short of bread, and it frequently happened that we had a surplus of meat. It is true that coffee, sugar and beer were often not to be had even at high prices, while in Moravia we sometimes ran out of wine. But in Bohemia we had local wine in plenty, especially in the camp at Melnik in 1757. You know how things are in wartime: if you want to be really comfortable, you ought to stay at home.

Similar tributes about life on the other side can also be found, an English volunteer in the Austrian army even maintaining that his colleagues did not desert because they were ‘well paid, well dressed and well fed’. So there is a great deal to be said for Sir Michael Howard’s canine metaphor to describe eighteenth-century warfare:

It might be suggested that it was not the least achievement of European civilisation to have reduced the wolf packs which had preyed on the defenceless peoples of Europe for so many centuries to the condition of trained and obedient gun dogs–almost, in some cases, performing poodles.

This verdict has been confirmed, albeit more prosaically, by Fritz Redlich who, in a general account of military depredation between 1500 and 1815, concluded: ‘The eighteenth century experienced a fundamental change in outlook and attitude towards looting and booty.’ As we shall see later in a different context, there was a return to the bad old days when the hordes of the French Revolution were unleashed on Europe. For the time being, however, another horseman of the Apocalypse had had his mount muzzled if not gelded.

MORTALITY–PLAGUE

It will be recalled that the hapless people of Malt complained not only about ‘this dismal, wretched war’ but also about the ‘raging pestilence’ which had come in its wake. Some victims were murdered by Polish soldiers, a few may have starved to death, but most died from plague. This was the third and greatest source of mortality, although it very often combined with the other two, for bodies enfeebled by hunger were easier prey for pathogens, and it was often armies that spread the epidemics. Günther Franz, in the study of German population losses during the Thirty Years War referred to earlier, argued that violent deaths were much less numerous than had once been supposed–it was plague that had been the main killer.

In the twenty-first century, when epidemic disease is both rare and understood, it is difficult to imagine a time when it was common and not understood at all. With our life expectancy of between seventy-five and eighty years, depending on sex and geographical location, and set to continue increasing to one hundred and beyond, death can be disregarded as something that happens to other people. When life expectancy lay between twenty-five and forty, again depending on class, gender and geographical location, death had terrifying immediacy. In England mortality worsened during the third quarter of the seventeenth century, life expectancy falling to its lowest point of around thirty years in the 1680s. It then improved to reach thirty-seven by 1700 and forty-two by the middle of the eighteenth century. Even so, when mourners gathered around an English graveside to hear the clergyman intoning the words of the Book of Common Prayer of 1662–‘in the midst of life we are in death’–they knew that he was telling the truth. Three years after those chilling words were published, the Great Plague of London killed perhaps between 80,000 and 100,000 in less than a year, out of a total population of fewer than 500,000. Its progress can be followed in a number of contemporary sources, the best being the diary of Samuel Pepys. Even his naturally ebullient disposition was chastened by the rapidly mounting death toll. On 26 July 1665 he recorded: ‘The Sickenesse is got into our parish this week; and is hot endeed everywhere, so that I begin to think of setting things in order, which I pray God enable me to put, both as to soul and body.’ Two days later he travelled to Dagenham, where he found the people so terrified of contagion from London visitors that he exclaimed ‘Lord, to see in what fear all the people here do live would make one mad’. Back in the capital on the following day, a headache ‘put me into extraordinary fear’. By the middle of August he could write ‘The people die so, that now it seems they are fain to carry the dead to be buried by daylight, the nights not sufficing to do it in.’ Particularly alarming was the death of his physician on 26 August. And so on.

Good luck and Pepys’s natural high spirits got him through the dark days of the late summer and autumn, after which mortality rates began to fall. Even his anxiety had not prevented him from indulging his two favourite passions–making money and philandering–to such an extent, indeed, that he could record complacently on the last day of the year: ‘I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague-time.’ This turned out to be last major outbreak of bubonic plague in England, thus bringing to an end a sequence which had begun back in the mid-fourteenth century with the Black Death. The nature of the plague is now well established. The bacillus is transmitted by the bite of a variety of flea (Xenopsylla cheopis) which normally lives parasitically on rats. When the bacillus becomes particularly intense and the rats start to die, the fleas need to find alternative hosts from which to draw blood. The most promising candidates are humans living in the vicinity of the rats. The flea-bite is followed by an incubation period of usually three to six days, although it can be as short as thirty-six hours and as long as ten days. Then the victim is afflicted by shivering, vomiting, acute headache and pain in the limbs, giddiness, extreme sensitivity to light and a high temperature (c. 40°C). Inside the body, the bacteria invade the lymph nodes, producing one or more swellings (the eponymous ‘buboes’) in the neck or the groin and internal bleeding. In between 50 and 75 per cent of cases death follows in approximately two weeks, ultimately as a result of respiratory failure. Even more deadly, although less common, are pneumonic plague and septicæmic plague, which (unlike the bubonic variety) can be easily spread from human to human.

In short, plague depended on a quadrilateral relationship between the bacillus, the flea, the rat and the human. Unfortunately, seventeenth-century Europeans were blissfully ignorant of the nexus and so could do little to break it. Living cheek-by-jowl with the source of infection, they unwittingly encouraged its periodic visitations. The unsanitary conditions of early modern communities has been summed up with particular eloquence by James Riley:

It was a habitat of stagnant waters and steaming marshes and fetid cesspits; of narrow, airless, and filth-ridden streets and passages; of hovels and grand buildings without ventilation; of the dead incompletely isolated from the living. It was, we can now see, a habitat in which the micro-organisms of disease (and the living vectors that transmit those micro-organisms and other pathogenic matter) thrived…It is inescapable to suppose that fleas, lice, houseflies, mosquitoes, rodents, and other small animals and insects which act as living disease vectors and vector hosts existed in stupendous numbers in these conditions. It was the golden age of these organisms.

Some idea of the havoc inflicted by the plague can be gained from simple statistics: Naples lost about half of its population and Genoa 60 per cent in 1656; Marseilles and Aix-en-Provence lost half in 1721; Reggio di Calabria lost half and Messina 70 per cent in 1743; Moscow lost 50,000 or about 20 per cent in 1771–2; and so on. Behind these stark figures, however, lie deep and dark economic, social, cultural and psychological chasms of grief and suffering. One example must suffice. It was in 1647 that there began what proved to be, in the words of Antonio Dominguez Ortiz, ‘the greatest catastrophe to strike Spain in the early modern period’, when the first case of plague was reported in Valencia. From there it spread through Aragon and Catalonia to the Balearic Islands and Sardinia, decimating the population as it went. In Barcelona, every possible precaution was taken to prevent infected people entering the city, but in vain. Shortly after New Year’s Day 1651 plague was established there. By the time it began to relinquish its grasp in late summer, 45,000 people had died. Observing it all was the tanner Miquel Parets, who left a harrowing record of its effect on his family. In quick succession he lost his wife, his baby daughter and two of his three sons:

God took our little girl the day after her mother’s death. She was like an angel, with a doll’s face, comely, cheerful, pacific, and quiet, who made everyone who knew her fall in love with her. And afterwards, within fifteen days, God took our older boy, who already worked and was a good sailor and who was to be my support when I grew older, but this was not up to me but to God who chose to take them all. God knows why He does what He does, He knows what is best for us. His will be done. Thus in less than a month there died my wife, our two older sons, and our little daughter. And I remained with four-year-old Gabrielo, who of them all had the most difficult character.

In Barcelona, as elsewhere, the outbreak of plague led to a breakdown of social order, as the healthy struggled to get out of the city while the going was good, the wealthy sought to buy their way out of quarantine restrictions, and the criminals took advantage of the collapse of law and order. For the survivors everywhere, the rewards could be great, as the acceleration of inheritances concentrated property ownership. The greatest beneficiary of all was the Church–indeed it could not lose, for it was the recipient of benefactions inspired both by hope during the outbreak and by gratitude after it. Catholic Europe is still covered with architectural evidence of this confidence in the power of the Almighty to ward off disease, in the shape of chapels, statues and various votive offerings to the ‘plague saints’ St Rochus (also the patron saint of dogs and dog-lovers) and St Sebastian (also the patron saint of archers). Even if the plague did strike, eventually it would go away, thus confirming God’s infinite mercy. Grandest of all these monuments is surely Santa Maria della Salute, the great baroque church built at the entrance of the Grand Canal in Venice to celebrate the end of the great plague of 1631–2. Visually the most exuberant is the Plague Column erected on the Graben in Vienna by the Emperor Leopold I following the plague of 1679.

The most popular explanation for a visitation of the plague was divine wrath; consequently the most popular prophylactic was propitiation. At Marseilles in 1720, Archbishop Belsunce took the lead, dedicating his fellow citizens to the cult of the Sacred Heart and leading penitential processions. In Barcelona, Miquel Parets recorded:

There are no words to describe the prayers and processions carried out in Barcelona, and the crowds of penitents and young girls with crosses who marched through the city saying their devotions. The streets were constantly full of people, many greatly devout and carrying candles and crying out ‘Lord God, have mercy!’ It would have softened the heart of anyone to see so many people gathered together and so many little girls, all of them barefoot. To see so many processions of clergy and monks and nuns carrying so many crosses and so many rogations that there was not a single church nor monastery which did not carry out processions both inside and outside their buildings.

It was to no avail, and Parets was obliged to add, ‘but Our Lord was so angered by our sins that the more processions were carried out the more the plague spread’.

Two other techniques were employed to avert or arrest the plague. Least effective were the various magical and herbal remedies employed, such as the fumigation with juniper ordered by Peter the Great during the wave of plagues which attacked Russia between 1709 and 1713. If juniper were not available, he decreed that horse manure was to be used, ‘or something else which smells bad, as smoke is very effective against these diseases’. However, most public authorities did understand enough of the epidemics to appreciate the need for isolating the outbreaks and their victims. Most Italian cities, for example, boasted a public health authority or sanità, ready to go into action at the first sign of illness, excluding or quarantining travellers from infected regions, sealing off the houses of the afflicted, establishing pest-houses, disposing of corpses, and so on. Alas, there proved to be too many ways round the regulations: the infected fled, the sick were concealed, soiled garments were not burnt but used again, and plague-controllers were bribed. The need to import provisions meant that no city could be isolated entirely from the outside world, while municipal prohibitions of public gatherings were often overruled by the clergy’s penitential processions.

Yet the period 1648–1815 did see, first the retreat, and then the virtual disappearance of the plague from Europe: England was afflicted for the last time in 1665, central Europe in 1710, France in 1720–21, the Ukraine in 1737, southern Europe in 1743 and Russia in 1789–91. Numerous explanations have been advanced. It is possible that the black rat (Rattus rattus), which liked to live cheek-by-jowl with humankind, was replaced by the brown rat (Rattus norvegicus), which was less sociable. It is also possible that all rats developed a higher degree of immunity to the plague bacillus, so the fleas had less need to abandon them for human hosts. The increasing use of stone for dwellings, as opposed to wood, wattle and daub, probably created a less welcoming environment for rodents of all kinds. Another hypothesis speculates that the bacillus itself naturally transmuted into a less virulent form. The American scholar James Riley has argued that what he calls ‘the medicine of avoidance and prevention’ made an important contribution to the decline of all infectious diseases, singling out for special mention improved drainage, lavation, ventilation, interment, fumigation and refuse burial, the relocation of refuse-producing industries and waste sites, and cleaner wells. More effective quarantine regulations were also adopted by a number of European states. The most important was the Habsburg Monarchy which, following the reconquest of Hungary from the Ottoman Turks, issued strict regulations to keep out plague carriers. The long frontier which straggled for 1,200 miles (1,900 km) across the Balkan peninsula, from the Adriatic to the Carpathians, was turned into a great cordon sanitaire. The quarantine period for anyone wishing to cross the frontier from the east was twenty-one days in plague-free times, forty-two days if an outbreak was rumoured and eight-four days if the rumour was confirmed. Guards were under orders to shoot to kill anyone trying to evade the restrictions. Equally tough action was taken by the French government to confine the 1720 outbreak to Provence.

None of these possibilities can be a sufficient cause for the decline in the incidence and severity of plague. Nor can that decline be a sufficient cause for the increase in Europe’s population. In one of those tricks of which malevolent nature is so fond, just as plague was waning, other diseases were waxing. Influenza, typhoid fever, typhus, dysentery, infantile diarrhœa, scarlet fever, measles and diphtheria all played their part in keeping the mortality rate up. The great killer of the eighteenth century was smallpox, an air-borne virus which enters the human body through the mouth or nose, then multiplies in the internal organs, causing high fever and a rash which turns into blisters and then pustules. The lucky escape with pock-marked skin, caused when the pustules dry; the less fortunate will be made blind, deaf or lame (or any two of three); about 15 per cent will die. On occasions, the mortality rate could be much higher: between 1703 and 1707, for example, Iceland lost 18,000 of its original population of 50,000. In Dublin between 1661 and 1745 20 per cent of reported deaths were ascribed to smallpox. James Jurin, secretary of the Royal Society of London, estimated that smallpox had killed a fourteenth of London’s population between 1680 and 1743. At Lodève in Languedoc outbreaks in 1726 and 1751 increased the death rate by almost 200 per cent.

Among the high-profile casualties in this period were the Elector Johann Georg IV of Saxony, who was infected when he insisted on kissing his dying mistress good-bye; the Emperor Joseph I, whose untimely death in 1711 at the age of thirty-two gave a decisive twist to the War of the Spanish Succession; Louis XV, who was rumoured to have caught the disease from the pubescent peasant-girl he had raped; and the Elector Maximilian Joseph of Bavaria, whose untimely death in 1777 precipitated the War of the Bavarian Succession. As these examples demonstrate, smallpox was impeccably democratic, decimating the palace as well as the hovel. If less destructive than the plague, it was more ubiquitous. In Candide, Voltaire wrote that if two armies of 30,000 each met in battle, two-thirds of the combatants would be pock-marked. The position and severity of the scars were used as a means of identifying criminals and, significantly, it was thought worthy of comment if they were not marked. The figure usually given for total European deaths per annum from smallpox in the eighteenth century is 400,000, although this must be a very rough guess indeed. In 1800 in the German principalities of Ansbach-Bayreuth it was recorded that 4,509 people had died from smallpox, or about 1 per cent of the total population. As an ever-present memento mori, it also caught the attention of the poets like Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, who contracted the disease in 1715 at the age of twenty-six. She survived the ordeal but at the expense of her beauty, as she recorded the following year:

How am I changed! alas! how am I grown

A frightful spectre, to myself unknown!

Where’s my complexion? where the radiant bloom,

That promised happiness for years to come?

Then, with what pleasure I this face surveyed!

To look once more, my visits oft delayed!

Charmed with the view, a fresher red would rise,

And a new life shot sparkling from my eyes!

Ah! faithless glass, my wonted bloom restore!

Alas! I rave, that bloom is now no more!

MEDICINE

Yet in this case it really was darkest before dawn. It was as a pock-marked spectre that Lady Mary travelled to Constantinople with her husband, the British consul in the city. There she found that Turkish peasant women had found a way of preventing the disease through a form of inoculation. As she explained in a letter to a friend in 1717:

Apropos of distempers, I am going to tell you a thing that will make you wish yourself here. The smallpox, so fatal and so general among us, is here entirely harmless by the invention of engrafting, which is the term they give it. There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation every autumn in the month of September when the great heat is abated…They make parties for the purpose…the old woman comes with a nutshell full of the matter of the best sort of smallpox, and asks what veins you please to have open’d. She immediately rips open that you offer to her, with a large needle (which gives you no more pain than a common scratch), and puts into the vein as much matter as can lie upon the head of her needle, and after that, binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell, and in this manner opens four or five veins.

These enterprising ladies were exploiting what was common knowledge everywhere–that a mild form of smallpox granted immunity for life. The technique may have been known already in western Europe too, but it was certainly Lady Mary’s proselytizing that led to its popularization. Although she could not set a personal example herself, as she already enjoyed immunity, she did the next best thing by having her five-year-old daughter inoculated when she returned to England in 1721. Her example was quickly followed by the Prince of Wales, who had both his daughters inoculated. Other social leaders to set examples included the duc d’Orléans, Frederick the Great of Prussia, the Empress Maria Theresa, the King of Denmark and Catherine the Great of Russia. It proved to be uphill work, not least because inoculation was not without its dangers. There was another major outbreak in London in 1752, when 17 per cent of all deaths were attributed to the disease. This concentrated the minds of potential victims everywhere, with the result that there was a rapid increase in the rate of inoculation during the second half of the century. Members of the Sutton family, who toured rural areas offering the treatment, claimed to have inoculated 400,000 in the thirty years after 1750. The dramatic effect inoculation could have on mortality rates is shown by a number of local studies which demonstrate that by the end of the eighteenth century, inoculation had spread down from monarchs to the common people.

A second breakthrough came at the very end of the century when an English country doctor, Edward Jenner, discovered the much safer and less elaborate technique of vaccination. He had noticed that infection with cowpox, a disease that is relatively benign when contracted by humans, granted immunity against smallpox. In 1796 he inoculated an eight-year-old boy with pus taken from the pustule of a milkmaid infected with cowpox. The boy suffered nothing worse than a mild fever, but when inoculated a short time later with the smallpox virus he proved to be immune and experienced no ill effects whatsoever. This discovery was publicized by Jenner in An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, published in 1798. By 1801 it had gone through two more editions and the technique was well on its way to gaining universal acceptance. It was made compulsory in a number of continental countries: in Sweden, for example, where deaths from smallpox per 100,000 fell from 278 in the late 1770s to 15 in the 1810s. In Bavaria, where the King set a personal example and then made it compulsory in 1807, total deaths from the disease fell from c. 7,500 per annum to 150 and then to zero by 1810. Napoleon had his entire army vaccinated. When Jenner wrote to him to ask for the liberation of a British prisoner of war, Napoleon is reported to have replied: ‘Anything Jenner wants shall be granted. He has been my most faithful servant in the European campaigns.’

Smallpox was not eradicated from the world until 1977, according to the World Health Organization, but it had ceased to be a serious killer in Europe by 1815. Its virtual eradication was a rare example of an unequivocal success story for medicine in this period. It also provides a good example of how folk-remedies (the Turkish peasant women’s ‘smallpox parties’) could combine with scientific observation and experimentation (Jenner’s vaccination) to produce real improvements in public health and reduce mortality. Much more typical of early modern attitudes were the other treatments used to combat smallpox. They were based on the Hippocratic-Galenic tradition which still dominated western medicine despite–or Perhaps because of–the antiquity of its eponymous founders (Hippocrates had lived 450–370 BC and Galen of Pergamum AD 129–200). At its heart lay the belief that human health was determined by the interrelationship between four ‘humours’ in the body. These were blood (hot and wet), black bile (cold and dry), yellow or red bile (hot and dry) and phlegm (cold and wet). According to time of life or time of year, any one of these humours could become predominant, with adverse effects. Too much black bile led to melancholy, too much phlegm led to torpor, too much red bile led to belligerence, and so on. The task of the physician was to restore the desired balance by draining off any excess.

So the preferred treatment of early modern medicine took the form of laxatives, emetics, dehydration and phlebotomy, to encourage purging, vomiting, sweating and bleeding respectively. As Edward Topsell defined the objective in the early seventeenth century: ‘the emptiyng or voiding of superfluous humors, annoying the body with their evill quality’. That is why so much literature of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries refers to the arrival of the barber-surgeon with his bleeding-cups and leeches as soon as illness struck. Indeed, the physician was often referred to as a ‘leechman’ who charged a ‘leech-fee’ and worked at a ‘leech-house’ (hospital). For the smallpox victim, it need hardly be said, none of these treatments did any good whatsoever, on the contrary. Nor did such exotic remedies as the ‘red cure’, which required the patient to dress in red clothes, sleep in a bed surrounded by red drapes and drink red-coloured fluids. Yet such was the authority of humoralism that its precepts were accepted by most without question. Samuel Pepys had himself bled when he thought he was ‘exceedingly full of blood’ and believed that it would improve his failing eyesight. Rare indeed was the strong-minded individual such as the Princess Palatine, of whom Madame de Sévigné recorded when she first arrived at Versailles in 1670: ‘she has no use for doctors and even less of medicines…When her doctor was presented to her, she said that she did not need him, that she had never been purged or bled, and that when she is not feeling well she goes for a walk and cures herself by exercise.’

There was no lack of medical services on offer in the early modern period, indeed there was an embarrassment of riches. For most patients, the first port of call was the household’s fund of accumulated wisdom, supported by herbal remedies and magical invocation. If a member of the family was literate, one of the many printed manuals, such as Samuel Tissot’s Avis au peuple sur la santé (1761) or William Buchan’s Domestic Medicine (1769) could be consulted. Resort could also be had to the local wisewoman or wiseman, the village priest, the blacksmith (if bones needed setting) or even the lady of the manor. A community might be lucky enough to have in its midst an individual with special powers, such as the seventh son of a seventh son, or a natural healer identified by being ‘born with the caul’ (i.e. with a piece of the placenta sticking to his head). There were plenty of travelling salesmen and quack doctors roaming the country, peddling patent medicines in the style of Dr Dulcamara of Donizetti’s L’Elisir d’amore. And there were also, of course, the official men of medicine–the physicians, the barber-surgeons and the apothecaries. There was no need to confine oneself to just one of these sources of medical advice and probably most sick people sought a second or third opinion.

Any temptation to divide these various resources into the scientific and the superstitious should be resisted. The former often did more harm than good, the latter often did more good than harm. A striking example of the shadowy relationship between the two was provided by the discovery of the cardiotonic properties of the foxglove plant by the Shropshire physician William Withering in 1775. Unable to help one of his patients with a serious heart condition, he was suitably embarrassed when the patient obtained a herbal tea from a gypsy-woman and promptly recovered. Withering systematically tested each of the brew’s twenty-odd ingredients until he had isolated foxglove as the benefactor. The digitalis purpurea the plant produces increases the intensity of the heart muscle contractions while reducing the heart rate, and can also be used to treat dropsy. After extensive trials on animals and human patients, Withering published in 1785 An Account of the Foxglove and Some of its Medical Uses etc; With Practical Remarks on Dropsy and Other Diseases which advertised its curative properties to the world. It has been used ever since. There were several other ‘folk-remedies’ which turned out to be based on sound science, such as willow-bark tea, which contained salicylates, the active ingredient in aspirin, or ‘Jesuit bark’, the bark of the cinchona tree which contains quinine. There was plenty to be said for preferring the practical experience of the wisewoman to the book-learning of the quack. Thomas Hobbes observed: ‘I would rather have the advice or take physick from an experienced old woman that had been at many sick people’s bedsides, than from the learnedst but unexperienced physician.’

Successes such as inoculation, vaccination or digitalis were few and far between. Almost all the staples of modern medicine–germ theory, general anaesthesia, radiology, antibiotics, and so on–were discoveries of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. For most patients in most places, the situation in 1815 was not so very different from that of 1648. In four ways, however, there can be said to have been progress, in the sense that the chances of patients receiving beneficial treatment improved. First, there was a fitful but definite move away from a humoral view of disease to one centred on the material structure of the body and employing a mechanical metaphor to understand its workings. The chief theoretical influence here was Descartes, whose rationalist philosophy divided soul from body, thus allowing the latter to be studied for its own sake and on its own terms. The chief practical influence was the growing practice of conducting post-mortems, which boosted anatomy and pathology at the expense of humoral theory. A landmark was the publication in 1761 by Giovanni Battista Morgagni of Padua of De Sedibus et Causis Morborum per Anatomen Indagatis Libri Quinque (The Seats and Causes of Diseases Investigated by Anatomy in Five Books), which described 640 post-mortems in detail, relating the state of the organs after death to the clinical symptoms displayed during life.

Secondly, in a few places there developed clinical training, which gave aspiring physicians the opportunity to learn their profession at the bedsides of real patients. The most influential figure here was Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738), professor of medicine at the University of Leiden in the Dutch Republic, who applied Cartesian dualism to physiology. He did not invent clinical training, which dates back to sixteenth-century Pavia, but he did popularize it. His clinic came to be a most important institutional influence on the development of eighteenth-century medicine. It was to Leiden that John Monro sent his son Alexander to be trained in anatomy, as part of his plan to give the University of Edinburgh a faculty of medicine, duly established in 1726. It became the most important centre of medical research and training in the British Isles, not least because it was closely linked to the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, founded three years later. Similar institutions for clinical training were established in Halle, Göttingen, Jena, Erfurt, Strasbourg, Vienna, Pavia, Prague and Pest. Perhaps significantly, it was not the university but the hospital that provided the institutional base for medical progress. At the University of Oxford, the primary duty of the Regius Professor of Medicine was to lecture twice a week during term on the texts of Hippocrates or Galen. Even that modest requirement proved too much for Thomas Hoy, Regius Professor from 1698 to 1718, who preferred to reside in Jamaica and appointed a deputy (who in turn appointed a deputy). Hoy was not untypical: the official history of the University records gloomily: ‘The holders of the office between 1690 and 1800, with minor exceptions, performed their duties with so little commitment that they merit no more than passing mention.’

A third form of progress was provided by voluntary movements of various kinds. There is no reason to suppose that human nature became more charitable in the eighteenth century, but the proliferation of private initiatives to relieve suffering was certainly striking. Whether it was the Medical Institute for the Sick-Poor of Hamburg, set up ‘to return many upright and honest workers to the state’ and ‘to reduce distress of suffering humanity’, the Society for Maternal Charity to serve ‘a class of poor for whom there are neither hospitals nor foundations at Paris, namely the legitimate infants of the poor’, or the self-explanatory National Truss Society for the Relief of the Ruptured Poor of London, the amount of medical attention available greatly increased. This phenomenon appears to have been particularly common in Great Britain, although this may simply reflect greater knowledge. Of special importance for medicine was the ‘voluntary hospital movement’, so-called because the hospitals in question were founded by groups of charitable individuals. The first was the Westminster Infirmary, founded in 1720, followed in London by St George’s, the London and the Middlesex. At least thirty more were founded in the provinces, among them Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Trumpington Street, Cambridge, founded in 1766 following a bequest from a former bursar of St Catharine’s College ‘to hire and fit up, purchase or erect a small, physical hospital in the town of Cambridge for poor people’.

Lastly, there was certainly a marked increase in the number of formally educated and certified practitioners. Three broad categories can be identified: at the summit were the physicians, academically trained, officially licensed and enjoying highest status and highest fees. More disparate were the apothecaries and the barber-surgeons, usually organized in guilds and treated as craftsmen. As the name of the latter group suggests, their primary function was to dress hair. They could turn their hand to simple medical tasks such as extracting teeth, lancing boils or setting bones, but usually were prudent enough to work within their limitations. The development noted above of the mechanistic view of the human body and the accompanying development of anatomy led to a corresponding expansion in the barber-surgeons’ horizons and the dropping of their tonsorial function. In 1745 the London Company of Surgeons broke away from the Barbers, completing their elevation to professional status with a royal charter in 1800 which made them the Royal College of Surgeons. In France, conventional craft-training for surgeons was ended in 1768. Everywhere there was a gradual convergence of training for physicians and surgeons, with a consequent elevation in status for the latter.

Between 1648 and 1815 there were few decisive medical innovations, but there was probably more change than in the previous millennium, especially in the way in which the working of the human body was regarded. It seems appropriate, therefore, to end this section with the optimistic view of the future voiced in 1794 by William Heberden:

I please myself with thinking that the method of teaching the art of healing is becoming every day more conformable to what reason and nature require, that the errors introduced by superstition and false philosophy are gradually retreating, and that medical knowledge, as well as all other dependent upon observation and experience, is continually increasing in the world. The present race of physicians is possessed of several most important rules of practice, utterly unknown to the ablest in former ages, not excepting Hippocrates himself, or even Aesculapius.

WOMEN, SEX AND GENDER

In 1703 Sarah Egerton published a collection of poems entitled Poems on Several Occasions, including ‘The Emulation’, whose opening lines are:

Say, tyrant Custom, why must we obey

The impositions of thy haughty sway?

From the first dawn of life unto the grave,

Poor womankind’s in every state a slave,

The nurse, the mistress, parent and the swain,

For love she must, there’s none escape that pain.

Then comes the last, the fatal slavery:

The husband with insulting tyranny

Can have ill manners justified by law,

For men all join to keep the wife in awe.

Moses, who first our freedom did rebuke,

Was married when he writ the Pentateuch.

They’re wise to keep us slaves, for well they know,

If we were loose, we soon should make them so.

She wrote with the depth of emotion inspired by personal experience. As a penalty for writing a long verse satire The Female Advocate at the precocious age of fourteen (or so she claimed in her autobiography), she was sent away from London by her middle-class parents to live with relations in rural Buckinghamshire and was then forced into a loveless marriage with a lawyer. Released from this servitude by the death of her husband, she then jumped back into the fire by marrying a widower twenty years older than herself in c. 1700. Whatever material advantages the Rev. Thomas Egerton brought her–he was rector of Adstock–they were not sufficient to expunge memories of Henry Pierce, a humble clerk with whom she was in love. The unhappy couple’s early attempt at divorce was frustrated by legal barriers, so they were forced to struggle on in a notoriously stormy marriage. Another female poet, Mary Delariver Manley, witnessed a ‘comical combat’, in which both Egertons resorted to violence, he by pulling her hair, she by throwing food. After the death of her second husband in 1720, Sarah enjoyed just three years of comfortable, and one hopes peaceful, widowhood before expiring herself at the age of fifty-three.

In this brief biography can be found some, but by no means all, of the problems encountered by women in early modern Europe: parental tyranny, the arranged marriage, the loveless marriage, and the inability to divorce. At least poor Sarah had the literary skill to leave a record of her resentment. Nor was she a lone voice. In the very same year that she wrote the lines quoted above, Mary Chudleigh published Poems on Several Occasions, including ‘To the Ladies’, whose first lines are:

Wife and servant are the same,

But only differ in the name:

For when that fatal knot is tied,

Which nothing, nothing can divide,

When she the word Obey has said,

And man by law supreme has made,

Then all that’s kind is laid aside,

And nothing left but state and pride.

In her case, it was Sir George Chudleigh Bart., Devon squire, who was displaying ‘state and pride’, although he did also give her six children, only two of whom survived infancy. Although she never criticized her husband directly, it can be inferred with some confidence that he was less than ideal. Two years earlier, in 1701, Lady Mary had written ‘The Ladies’ Defence’ in answer to a sermon advocating the absolute submission of wives to husbands preached by a nonconformist minister called John Sprint. In the preface she stated that what made the greatest contribution to marital unhappiness was ‘Parents forcing their Children to Marry, contrary to their Inclinations; Men believe they have a right to dispose of their Children as they please; and they think it below them to consult their Satisfaction’. The poem is a discussion between three men, one of them an Anglican clergyman, and a woman. The chief spokesman for the male camp is the aptly named Sir John Brute, who takes the view that ‘Those worst of Plagues, those Furies call’d our Wives’ can, and should, be treated roughly:

Yes, as we please, we may our Wives chastise,

‘Tis the Prerogative of being Wise:

They are but Fools, and must as such be us’d.

In her reply, the female mouthpiece–Melissa–gives as good as she gets, apostrophizing men as arrogant tyrants, complacent hypocrites, sadistic brutes, self-indulgent sots, idle voluptuaries, ‘Empty Fops, or Nauseous Clowns’, just to mention a few of her epithets. Sir John is given strong clerical support from the unnamed parson, who patiently explains to Melissa the great gulf separating men from women:

Your shallow Minds can nothing else contain,

You were not made for Labours of the Brain;

Those are the Manly Toils which we sustain.

We, like the Ancient Giants, stand on high,

And seem to bid Defiance to the Sky,

While you poor worthless Insects crawl below,

And less than Mites t’our exalted Reason show.

Because it was Eve’s fault that mankind was expelled from paradise, he asserts, it is only right that her successors should be enslaved. Melissa replies that any intellectual limitations suffered by women are caused by men:

‘Tis hard we should be by the Men despis’d

Yet kept from knowing what would make us priz’d:

Debarred from Knowledge, banish’d from the Schools,

And with the utmost Industry bred Fools.

Sir John promptly confirms the justice of this complaint by observing that women should not be allowed to read, for ‘Books are the Bane of States, the Plagues of Life, / But both conjoyn’d when studied by a Wife’. The fourth member of the party, Sir William Loveall, the sort of bachelor so very keen to establish his heterosexual credentials by boasting of his conquests, tells Melissa that members of the fair sex should content themselves by being just that–fair–and not trouble their pretty little heads with matters they cannot understand. Faced with Brute’s misogyny, the parson’s theology and Loveall’s condescension, Melissa can only look forward to a more equitable existence in the next world.