3

Trade and Manufacturing

TRADE

When Joseph Palmer visited Bordeaux in 1775, he was deeply impressed, recording that it

yields to very few cities in point of beauty; for it appears to have all that opulence which an extensive commerce can confer. It is finely situated on the banks of the Garonne…The quay which is extended on a straight line, for more than two miles, with a range of regular buildings, cannot fail of striking the eye with admiration; which is encreased by the noble appearance of an immense rapid river, and the multitude of ships and vessels which trade here.

Twelve years later the peripatetic agronomist Arthur Young confirmed this favourable verdict. In view of his notorious propensity for making unflattering comparisons between conditions at home in England and what he found in France, his impressions are particularly authoritative: ‘Much as I had heard and read of the commerce, wealth and magnificence of this city, they greatly surpassed my expectations. Paris did not answer at all, for it is not to be compared to London; but we must not name Liverpool in competition with Bordeaux.’ As he was ferried across the river, he added, ‘The view of the Garonne is very fine, appearing to the eye twice as broad as the Thames at London, and the number of large ships lying in it, makes it, I suppose, the richest water-view that France has to boast.’

Visual evidence of the accuracy of this description can be found by any present-day visitor, for the city’s architecture demonstrates that the eighteenth century was its heyday. For all its splendour, the Place Royale is not the most characteristic site, for it was replicated in other French cities. The same could be said for the new archiepiscopal palace facing the cathedral. It is the great opera-house–the Grand Théâtre–designed by Victor Louis and built between 1772 and 1780 which best exemplifies the Bordeaux boom. What makes it special is not its size, for although it is very large, it is not as big as, say, San Carlo in Naples or La Scala in Milan. Nor is it the fact that it was a free-standing building, for Frederick the Great’s opera-house on Unter den Linden in Berlin had anticipated this feature by more than a generation. The Bordeaux opera-house is different because in effect it is three buildings, incorporating not just a theatre but also a concert-hall and a staircase. To identify the staircase as a space of equal importance is less perverse than might appear, for the foyer and staircase were as large as the auditorium. It was there to allow members of Bordeaux high society the opportunity to parade before each other in all their finery–to see and be seen. As Victor Louis grasped, in an opera-house the audience is as important a performer as the singers on stage. In an opera-house built for a king, it is the royal box that is the chief architectural feature, but in a public opera-house built for a great commercial city such as Bordeaux, it is the foyer, staircase and other public rooms. Arthur Young certainly grasped the close connection between commerce and culture in the city:

The theatre, built about ten or twelve years ago, is by far the most magnificent in France. I have seen nothing that approaches it…The establishment of actors, actresses, singers, dancers, orchestra, etc. speaks the wealth and luxury of the place. I have been assured that from thirty to fifty louis a night have been paid to a favourite actress from Paris…Pieces are performed every night, Sundays not excepted, as everywhere in France. The mode of living that takes place here among merchants is highly luxurious. Their houses and establishments are on expensive scales. Great entertainments, and many served on [silver] plate. High play [gambling] is a much worse thing; and the scandalous chronicle speaks of merchants keeping the dancing and singing girls of the theatre at salaries which ought to import no good to their credit.

This conspicuous display derived from commerce. Between 1717 and 1789 Bordeaux’s trade increased on average by 4 per cent per annum, multiplying almost twenty times in value, from 13,000,000 livres to almost 250,000,000 livres; its share of French commerce increased from 11 to 25 per cent and its population doubled from 55,000 to 110,000. Although some of this prosperity derived from increased wine sales to the rest of Europe, the lion’s share came from the West Indian colonies –Guadeloupe, Martinique and, above all, Saint Domingue, the greatest sugar-producing region in the world. The sugar production of the last-named increased from 7,000 tons in 1714 to 80,000 tons in 1789. Moreover, it was not just the merchant-princes who grew rich on the proceeds, for Bordeaux’s whole economy was moulded by its leading sector. For example, 700–800 men were employed in the shipyards, 300–400 in the ropeworks, 300 in the sugar refineries, and so on.

As we shall see, the whole European economy expanded during the eighteenth century, but it was international trade that provided the most dramatic success story. The original impetus probably came from outside Europe. In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, there was a marked upturn in the Iberian Pacific, demonstrated by the customs receipts at Manila and Acapulco, which increased by 2,600 per cent in the fifty years before 1720. Simultaneously, a demographic surge in China created a corresponding demand which attracted growing numbers of British and Dutch merchants. The Chinese gold they brought back to Europe, together with the rapidly expanding output of Brazilian mines, helped to alleviate the chronic shortage of coin and, among other things, allowed the stablization of European currencies. With European colonial expansion on the move again after a century of stagnation, in North America, the Caribbean and the Far East, the scene was set for self-sustaining expansion. Between 1740 and 1780 the value of world trade increased by between a quarter and a third; indeed, in Alan Milward’s words, ‘the mid-eighteenth century was one of the most remarkable periods of trade expansion in modern history’. In France, the volume of foreign trade doubled between the 1710s and the late 1780s, but its value increased five times. French colonial trade increased in value by a staggering ten times during the same period.

The human cost of this great surge is revealed by more chilling statistics, for example that the number of slaves in the French West Indies increased during the course of the eighteenth century from c. 40,000 to c. 500,000 in 1789, with the price of each slave quadrupling during the same period, such was the demand for their labour. All the major maritime nations were involved in the trade. The Portuguese and the Dutch imported more than they needed for their own colonies, so sold on their surplus to the voracious Spanish and French producers. The British probably constituted the most dynamic national group; as Paul Langford has written, slavery was ‘one of the central institutions of the British Empire, one of the staple trades of Englishmen’. It was certainly the foundation for the prosperity of Liverpool, from which there were nearly 2,000 slave-trade departures between 1750 and 1780, compared with 869 from London and 624 from Bristol.

If the transatlantic trade provided the most startling statistics, the core of Europe’s trade remained within Europe. As Jacob Price has observed, it is remarkable how durable was the traditional ‘map of commerce’, whose main artery ran from the Baltic via the Low Countries to the Bay of Biscay and the Iberian Peninsula, with off-shoots to Norway, the British Isles and the Mediterranean. In the course of the sixteenth century, oceanic connections had been added to reach America and the Far East, but it was the Baltic–Cadiz route that remained the great employer of shipping. In 1660 it was dominated by the Dutch. Despite–or perhaps because of–the eighty-year struggle to break free from Spanish rule (only ending in 1648), the Dutch had put together a trading system of truly amazing size, complexity and prosperity. One simple statistic illustrates their predominance in European commerce: in 1670 their merchant marine totalled 568,000 tons, more than that of France, England, Scotland, the Holy Roman Empire, Spain and Portugal combined. The basis of Dutch trade was the huge surplus of grain, chiefly rye, produced by the Baltic countries, especially Poland-Lithuania. It was almost all shipped to the Dutch Republic, 80 per cent of it in Dutch ships. Around 40 per cent was then re-exported to feed the numerous parts of Europe, notably in the south, that were unable to feed their populations from their own resources. This plentiful supply of basic food allowed Dutch farmers to specialize, to concentrate on branches of agriculture best suited to their soil and climate, namely livestock, dairy products, vegetables, barley, hops, tobacco, hemp, flax, cole-seed (for lamp-oil) and various sources of dye (madder, weld and woad). Down their matchless waterways, these cash crops, and the articles manufactured from them, went to markets all over northern and western Europe. More important still, in terms of value, were the ‘rich trades’, the commodities such as spices, sugar, silk, dyestuffs, fruit, wine and silver that the Dutch gathered in southern Europe and took back to all points north. By the 1660s this branch of commerce was generating seven times as much profit as the bulk freightage from the Baltic. It also provided much of the raw materials that formed the basis of the Republic’s flourishing manufacturing sector: fine cloth, silks, cottons, sugar-refining, tobacco-processing, leather-working, carpentry, tapestry-weaving, ceramics, copper-working and diamond-cutting.

Part of the explanation of Dutch superiority was technological. From their first introduction at the very end of the sixteenth century, the famous fluyts (known to the English as ‘fluteships’ or ‘flyboats’) provided a sharp competitive edge. Thanks to the adoption by the Amsterdam shipyards of standardized designs and labour-saving devices, the fluyt maximized carrying capacity and minimized cost. It has been estimated that an English ship of 250 tons cost 60 per cent more to construct than its Dutch rival. As a dedicated carrier of bulk freight with no pretensions to be a warship, the fluyt was also much cheaper to run, requiring far fewer sailors–as few as ten for the 200-ton version, as opposed to the thirty for an English ship of comparable tonnage. The result was that Dutch shippers were able to undercut their competitors from other nations by between a third and a half. With that kind of advantage, the Dutch achieved an extraordinary dominance of the carrying trade. By the second half of the seventeenth century, they so dominated the Baltic as to make it appear a colony. The Swedish port of Gothenburg, for example, was built by the Dutch, owned by the Dutch and run by the Dutch–Dutch was even its official language. The Bishop of Avranche wrote in 1694:

It may be said that the Dutch are in some respects masters of the commerce of the Swedish Kingdom since they are masters of the copper trade. The farmers of these mines, being always in need of money, and not finding any in Sweden, pledge this commodity to merchants of Amsterdam who advance them the necessary funds. It is the same with tar and pitch, certain merchants of Amsterdam having bought the greater part of these farms of the King, and made considerable advances besides, so that the result is that these commodities and most others are found as cheap in Amsterdam as in Sweden.

Danish sovereignty was also heavily compromised by coercion on the part of the Dutch to secure most-favoured status for their ships passing through the sound separating the North Sea from the Baltic.

A second major branch of Dutch commerce was supplied by fishing. Not for nothing was their herring industry known as ‘the Great Fishery’. Each year, between late June and early December, a specialized fleet of buizen (known to the envious English as ‘busses’) followed the herring-shoals from the Shetlands to the Straits of Dover, catching colossal quantities as they went. The fish were salted, barrelled and sent back to the Maas ports for re-export, the Catholic parts of Europe proving particularly good customers. Out of season, the buizen went south to the Bay of Biscay or to Portugal to collect the huge amounts of high-quality salt needed in the curing process. In terms of total value, the Great Fishery vied with English cloth for the title of ‘greatest single branch of European commerce’. Less important but also lucrative was the cod-fishing in the North Sea and the whaling in the Arctic. The latter reached its peak in the 1680s, when the Dutch were sending 240 ships a year, returning with up to 60,000 tons of blubber to be turned into lamp-oil and soap.

The Dutch also exploited the resources of the East. In the last year of the sixteenth century, a number of ships returned to Amsterdam from the Spice Islands laden with, among other good things, 600,000 pounds (270,000 kg) of pepper and 250,000 (113,000 kg) pounds of cloves. As this precious cargo yielded a profit of more than 100 per cent, there was a rush to follow. When, three years later, the various companies were amalgamated to form the Dutch East India Company, one of the greatest commercial undertakings in European history was underway. At its peak, in the late seventeenth century, it was the richest corporation in the world, owning 150 trading ships and 40 ships of war, and employing 20,000 sailors, 10,000 soldiers and nearly 50,000 civilians. Dutch pre-eminence in south-east Asia first had to be wrested from the Portuguese. Showing irresistible energy and aggression, they chased the incumbents from one spice island after another. By 1660 the Dutch were in possession of Cochin (on the west coast of India), Malacca (on the west coast of the Malayan Peninsula), Indonesia (including Sumatra and Java), Borneo, the Celebes, the Moluccas, western New Guinea, Formosa and Ceylon. All that was left to Portugal in the Orient was Goa in southern India and Macao in China. Later attempts by the British to muscle in on the immensely lucrative spice trade were rebuffed with vigour, not to say brutality, notably at the infamous ‘Amboina massacre’ of 1623, dramatized by John Dryden forty years later to drum up support for the Second Anglo-Dutch War.

The total population of the Dutch Republic was only about two million, yet Dutch merchants seemed to be everywhere in the world, leaving their calling cards in the form of place-names–Cape Horn, Brooklyn, New Zealand, Van Diemen and Spitsbergen, for example. From 1625 until 1667 New York was a Dutch colony called New Amsterdam. They established a permanent presence in South America, the Carribbean and South Africa, as well as in eastern waters. Commenting on the ubiquity of the Dutch fleet in 1667, Sir William Batten, Surveyor of the Royal Navy, exclaimed to Samuel Pepys: ‘By God! I think the Devil shits Dutchmen!’ His fellow countryman Charles Davenant added a little later: ‘the trade of the Hollanders is so far extended that it may be said to have no other bounds than those which the Almighty set at the Creation’. Underpinning their global trading complex were the financial institutions of Amsterdam. Founded in 1609, its eponymous bank quickly eclipsed the traditional leaders, Venice and Genoa, as the centre of Europe’s money market. It was soon joined by a Loan Bank. Together with the Stock Exchange, which moved to a palatial new building in 1609, the banks gave Dutch merchants a head-start in managing their business affairs. Nowhere else could credit be obtained so easily, quickly and cheaply. Nowhere else could goods be insured with such facility. Symbolic of the methodical approach adopted by the Amsterdam agents was their introduction of printed forms for the registration of insurance policies. So superior were the services they offered that during the Third Anglo-Dutch War of 1672–4, the British fleet was insured at Amsterdam. For all Europe’s businessmen, a bill on Amsterdam was the accepted way of financing foreign trade. With this institutional infrastructure in place by the middle of the seventeenth century, the Dutch were in a position to establish quickly what Jonathan Israel has called ‘world trade primacy’ when peace returned in 1648.

Their primacy was to last a long time. In the middle of the next century, the Dutch still dominated the carrying trade: of 6,495 ships entering the Baltic in 1767, 2,273 (35 per cent) were Dutch. However, figures of this kind conceal a serious decline, both relative and absolute. Many of the Dutch ships now travelling to the Baltic were small vessels from Friesland and the Wadden Islands. The great bulk-carriers of Holland were much diminished. The bulk-carrying fleet of Hoorn, for example, fell from 10,700 lasts in the 1680s to 1,856 in the 1730s and 1,201 in the 1750s. The decisive period for the end of the Dutch Republic’s ‘Golden Age’ appears to have been the second quarter of the eighteenth century, when the ‘rich trades’ receded and the fishing industry collapsed. The contraction of ship-building was symptomatic of a wider decline, as the number of shipyards on the Zaan, to the north of Amsterdam, fell from over forty in 1690 to twenty-seven in the 1730s and twenty-three in 1750. Only the re-export of colonial produce continued to expand, but even in this sector there was a decline relative to the massive expansion achieved by the French and the British.

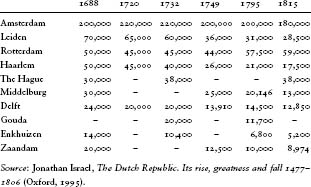

If the Dutch Republic had bucked the European trend in the seventeenth century by increasing its population and its wealth, it now went into reverse, just as general expansion was beginning everywhere else. Between 1600 and 1650 its population had increased from somewhere between 1,400,000 and 1,600,000 to somewhere between 1,850,000 and 1,900,000. But there it stuck. There may have been some slight increase to reach 1,950,000 in 1700 but the eighteenth century was marked by demographic stagnation. The first reliable census in 1795 recorded a total population of 2,078,000. More serious was the distribution of the population. At a time when Europe’s urban population was growing, many Dutch towns were experiencing de-urbanization, as Table 4 reveals.

Table 4. Changes in Dutch urban population 1688–1815

Behind the extraordinary figures for Haarlem and Leiden lie a collapse of the fine cloth industries which had made them two of the most prosperous communities in Europe. In the latter, annual production fell from 25,000 rolls in 1700 to 8,000 in the late 1730s.

The Dutch Republic had suffered the fate common to many other economies enjoying the initial advantage of being first in the field. So rapid was its expansion, so astounding was its wealth, that it was bound to attract the jealous hostility of other states. This was made all the more likely by the prevailing economic orthodoxy, which held that the amount of silver and gold coinage, or ‘specie’, in the world was finite and that therefore one country could only prosper at the expense of others. Sir Matthew Decker summed this up in 1744: ‘Therefore if the Exports of Britain exceed its Imports, Foreigners must pay the Balance in Treasure and the Nation grow Rich. But if the Imports of Britain exceed its Exports, we must pay Foreigners the Balance in Treasure and the Nation grow Poor.’ Moreover, as a state’s power was causally related to its possession of specie, the government had a duty to regulate the economy accordingly, by promoting exports and reducing imports. This led the English Parliament, for example, to pass the Navigation Acts of 1651, 1660 and 1696. These required all trade to and from English colonies to be carried in English ships and all colonial produce to be brought to English ports. A similar attitude was adopted by the French. In a report prepared for Louis XIV in 1670, Colbert wrote:

There is only a fixed quantity of money circulating in all of Europe, which is increased from time to time by silver coming from the West Indies. It is demonstrable that if there are only 150 million livres in silver circulating [in the kingdom], we cannot succeed in increasing [this amount] by twenty, thirty or fifty million without at the same time taking the equivalent quantity away from neighbouring states.

Like the English, Colbert had his sights set squarely on the Dutch, who, he alleged in the same report, handled nine out of every ten units of commerce passing in and out of French ports. They brought into France very much more than they took out, the balance being paid for by the French in hard cash, ‘causing both their own affluence and this realm’s poverty, and indisputably enhancing their power while promoting our weakness’. To correct the situation, in 1662 a tax of fifty sous per ton had been imposed on every ton of cargo carried in a foreign vessel. The result: ‘we have seen the number of French vessels increase yearly, and in seven or eight years the Dutch have been practically excluded from port-to-port commerce, which is [now] carried on by the French. The advantages enjoyed by the state from the increase in the number of sailors and sea-going men, and from the money that has remained in the realm, are too many to enumerate.’ Every time a European government imposed a mercantilist policy such as Colbert’s, the Dutch were affected adversely. In 1724, for example, the Swedes passed a ‘Commodity Act’, which barred foreign ships from their ports except when carrying the produce of the ship’s own nationality. This hurt both Swedish merchants and Swedish consumers, by driving up freight rates and prices. But it hurt the Dutch even more.

Both the English and the French also took direct action against Dutch commerce by waging war, the former in 1652–4, 1665–7 and 1672–4, the latter in 1672–8, 1689–97 and 1702–13. In all these conflicts, the Dutch showed that they could punch well above their weight. Such feats of arms as the raid on the Medway in 1667 or the three great victories over the combined Anglo-French fleet in 1673 showed that even a demographic imbalance of something in the order of fourteen to one could be overcome. In the long run, however, the God of Battles proved to be on the side of the big battalions. The overexertion necessitated by decades of incessant warfare eventually exhausted the Republic’s resources. In particular, the burden of taxation required to service the accumulated debt and maintain the armed forces inflicted structural damage on the Dutch economy. In 1678 the national debt was 38,000,000 guilders; by 1713 it had risen to 128,000,000. As early as 1659 Sir George Downing had marvelled: ‘it is strange to see with what readyness the people doe consent to extraordinary taxes, although their ordinary taxes be yett as great as they were duringe the warr with Spaine’, adding by way of illustration, ‘I have reckoned a man cannot eate a dishe of meate in an ordinary [inn] but that one way or another he shall pay nineteen excises out of it. This is not more strange than true’. At the end of the seventeenth century, Gregory King estimated that although the population of the Dutch Republic was less than half that of England, it was raising more public revenue–thanks to the fact that the average Dutch taxpayer was paying three times as much as his equivalent in England or France.

These high indirect taxes on consumption led to correspondingly elevated wages and diminished competitiveness. Wages for cloth-workers in Leiden were twice as high as those paid to workers across the frontier in the southern Netherlands and three times as high as in the neighbouring Prince-Bishopric of Liège (then an independent principality of the Holy Roman Empire). No wonder that by 1700 traditional customers of the Dutch were finding cheaper suppliers elsewhere. By this time they were also finding it more convenient to transport the goods in their own ships. Sooner or later it was inevitable that other shipbuilders would close the technological gap, construct their own versions of the fluyts, develop their own merchant marine and cut out the Dutch middle-man. Prussia’s direct trade with Bordeaux, for example, doubled between the 1740s and the 1780s. The dynamism the Prussians showed in military matters was also evident in commerce. At Stettin, the number of ships increased from 79 in 1751 to 165 in 1784. And they were getting bigger: the number of ships over 100 Lasten increased from two in 1751 to seventy-eight in 1784. In the Baltic there was growing competition from Scandinavian and Hanseatic shipping, with the Swedes developing a rival herring fishery at Gothenburg and the Norwegians supplanting the Dutch as the main suppliers of cod to the region. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Dutch cod fishery had shrunk to less than 20 per cent of what it had been in the 1690s. By the 1770s the Dutch had only just over 40 per cent of the Baltic grain trade, compared with its virtual monopoly a century or so earlier. They also found their traditional domination of the whaling industry challenged: in 1721, of the 355 vessels engaged in whale fishing around the coasts of Greenland, the lion’s share–251–were still Dutch, but there were now 55 from Hamburg, 24 from Bremen, 20 from the Biscayan ports of France and Spain and 5 from Bergen.

As the rest of Europe recovered from the Thirty Years War and developed their own commerce, there was decreasing need for the Dutch entrepôt. This did not mean that the great trading complex developed during the Golden Age collapsed in the eighteenth century. Several important sectors continued to expand, at least in absolute terms. Dutch merchants continued to show their old enterprise and energy in developing new branches, as in the lucrative coffee business in the East Indies. At home, however, there was undoubtedly a move away from manufacturing and trade towards finance, especially loans to foreign governments. With so many of the latter eager to pay 5 per cent and more in interest, it made good sense to move accumulated capital into banking. And so the Dutch Republic became what Charles Wilson has called ‘a rentier economy’, if not quite a parasite, then certainly a more passive player in Europe’s economy.

Of the countries moving in the opposite direction, the most spectacularly successful in relative terms was Russia. From being a remote and occasional supplier of raw materials in 1660, by 1815 it had emerged as a major commercial power. Peter the Great’s victory in the Great Northern War of 1700–21 brought control of the eastern Baltic, including the ports of Narva, Riga and Reval, not to mention his new creation of St Petersburg. The latter was founded only in 1703, yet by 1722 its turnover of freight was twelve times that of Archangel, previously Russia’s main port. With the ‘window on the west’ now secured, Russia’s trade with western Europe doubled between 1726 and 1749. Just as important, albeit often overlooked, were the acquisitions made in the south by Catherine the Great. The Treaty of Kutchuk Kainardja in 1774 brought a foothold on the Black Sea and the right for Russian merchants to navigate on it; the Convention of Ainali Kawak in 1779 added the right to pass through the Straits into the Mediterranean; the annexation of the Crimea in 1783, secured by the war of 1787–91, brought the northern coastline of the Black Sea under Russian control; the war of 1807–12 extended it almost to the Danube Delta. The three partitions of Poland of 1772, 1793 and 1795 advanced the frontier of the Russian Empire more than 300 miles (500 km) to the west.

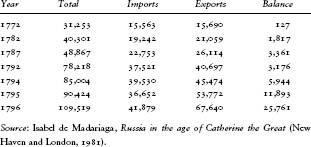

It took a long time for this transformation of the geopolitical situation to be realized in commercial terms. For much of the eighteenth century, Russia continued to be regarded by the west, and especially by its main customer, Great Britain, as a colony, i.e. as a source of raw materials and a market for manufactured commodities. Aware that the Russians lacked any kind of commercial infrastructure, the British drove a hard bargain in their trade treaty of 1734. Although the more onerous provisions were revised in a subsequent treaty of 1766, the basic exploitative outline remained the same. Achieving economic maturity was proving to be a long process: in 1773–7 the average number of Russian-owned ships in all Russian ports was only 227, and only between 12 and 15 of those over 200 tons were genuinely Russian. To put that statistic in perspective, of 1,748 ships visiting Russian ports during the same period, over 600 were British. That Russia had arrived as a maritime power, however, was advertised dramatically on 24–26 June 1770, when a fleet which had sailed from the Baltic via the North Sea infliced on the Turks at Chesme in the Aegean one of the most crushing defeats in the history of naval warfare. It was intended to pay commercial dividends, for it was followed by the establishment of diplomatic representation in trading centres. In the course of the next decade, sixteen consuls general and thirty consuls were appointed to cover the Baltic, North Sea, Atlantic and Mediterranean. The last two decades of the eighteenth century saw rapid expansion, spurred on by the opportunities presented by the new ports in the south, where Kherson was founded in 1778, Sevastopol in 1783 and Odessa in 1793. In 1794, 406 Russian ships sailed from Russian ports, still outnumbered by the British with 1,011, but clearly now constituting a merchant marine to be reckoned with. It had increased eight times between 1775 and 1787. Foreign trade also showed an impressive surge, as Tables demonstrates:

Table 5. Total Russian foreign trade (turnover in 000r.)

Indicative of this secular transformation of Russian commerce was the shift in its relationship with the British. When the trade treaty of 1766 was about to expire in 1786, the British found to their surprise and dismay that they could not renew it on the old terms. This should not have been surprising. Catherine the Great had given an indication of her intentions in 1780 when she formed the League of Armed Neutrality, a consortium of non-belligerents which, despite its name, was aimed squarely at British maritime supremacy. With a self-confidence born of the knowledge that they now had their own merchant navy and their own mercantile services, the Russians proved obdurate and the treaty lapsed. More alarming still for the British was the commercial agreement the Russians signed with the French in January 1787. This was adding insult to injury, not least because it had important strategic as well as political implications. Both the Royal Navy and the British merchant marine relied very heavily on Russia for their construction materials, not just timber for masts and planks but also timber derivatives such as pitch, tar, resin and turpentine, flax for sail-cloth and hemp for rope and cordage. Now that Russia had opened up direct trade links to the Mediterranean through the Black Sea, the awful possibility loomed that these ‘naval stores’ would be diverted to Britain’s mortal enemy.

The process was in fact already underway. In 1781 a French merchant based at Constantinople by the name of Anthoine had travelled to Kherson, St Petersburg and Warsaw to investigate this possibility. He then journeyed on to Versailles to report to the French authorities. In April 1783, with the war in America drawing to a close, the French foreign minister, Vergennes, urged the minister for the navy, Castries, to accelerate the project, lest the British take counter-measures. Anthoine was duly given the exclusive right to export naval stores to France through Kherson and was granted a credit of 100,000 livres on an Amsterdam bank. In 1784 he was joined at Kherson by a master-mastman to assist in the selection of appropriate masts. A contract was duly signed with the Polish magnate Prince Poniatowski for the delivery of 300 masting trees. A further consignment of 263 arrived at Marseilles in 1786. It is difficult to estimate what might have become of this trade. The masts actually delivered were smaller and of poorer quality than the French had hoped, and Anthoine showed more interest in trading on his own account than in promoting the national interest. In the event, the outbreak of war between Turkey and Russia in the summer of 1787 brought the project to an abrupt halt. In 1793 Catherine the Great responded to the execution of Louis XVI by cancelling the agreement.

Although not the main cause, that act of regicide facilitated the entry of Great Britain into the Revolutionary Wars, thus beginning the death-agony of French overseas trade. But even before that terminal crisis, there had been signs of strain. After wresting control of the Levant trade in the early eighteenth century, by the 1780s French merchants found themselves being undercut by cheaper textiles brought by English, German and Austrian competitors. By 1783 their market share had declined to around 40 per cent. That was the year in which the American colonists finally won recognition of their independence and it should also have been the year in which their French mentors and allies entered into their commercial kingdom. It was not to be. The French commercial system proved to be inflexible, over-reliant on the protected colonial trade and especially on its re-exports, which accounted for more than a third of all exports in the 1780s. More specifically still, it was over-reliant on Saint Domingue, which generated three-quarters of trade with the colonies, most of the re-exported goods and absorbed nearly two-thirds of France’s foreign investments. The growing exhaustion of over-exploited soil and the rising price of slaves were already enfeebling this golden goose when it was abruptly decapitated by the outbreak of a great slave revolt in August 1791. The French never regained control of the island.

That by itself was enough to reduce the trade of Bordeaux by a third in less than a year, but much worse was to come. After the declaration of war by the National Assembly on Great Britain and the Dutch Republic on 1 February 1793, the Royal Navy ruled the waves to such effect that French overseas trade virtually collapsed. Lorenz Meyer, a Hamburg merchant, reported from Bordeaux in 1801:

The former splendour of Bordeaux is no more…The devastation and loss of the colonies have wiped out commerce and have ruined with it the prosperity of the first city of France. This can be seen everywhere. The stock-exchange is still packed with merchants, but most of them go there only out of habit. Business is a rare event. The only branch not to have disappeared is the domestic trade in wine.

In 1789 French re-exports to Hamburg, mainly of sugar and tobacco, had been worth 50,000,000 livres. In 1795–a better year than the previous two–France sent just 291 tonneaux of sugar, mainly in neutral vessels, whereas the British sent 25,390 tonneaux. In that same year, all French foreign trade had fallen to just 50 per cent of what it had been in 1789. In the first seven years of the Revolution, the proportion of all economic activity in France provided by overseas trade had fallen from 25 per cent to 9 per cent. Even in 1815 it was still only 60 per cent of what it had been in 1789. This decline had a corresponding impact on the manufacturing hinterlands. At Marseilles, for example, the value of industrial production fell by three-quarters between 1789 and 1813.

The great lesson of the eighteenth century was that the key to commerce was shipping and the ability to protect that shipping. It was a lesson that the French were sometimes unwilling and often unable to learn. At times it proved possible for naval and mercantile interests to make their voices heard at Versailles, notably during the long ministry (1661–83) of Colbert, but more often than not they were shouted down by the military. In the fierce competition for scarce resources, tradition and geography favoured the army. Periodic efforts to construct a navy capable of taking on the Dutch, or–later–the British, invariably faltered. Consequently, all the decisive naval engagements ended in French defeats. This endemic failing was casually linked to the relative weakness of the French merchant navy. It was never more than half the size of that of Great Britain, despite a demographic superiority of three to one, a long coastline and excellent ports on both the Atlantic and the Mediterranean. Sir John Habbakuk described this failure as ‘one of the most curious features’ of the economic history of the period. In 1767, 203 ships passed through the sound from the Baltic en route to French ports and 299 travelled back in the opposite direction–but only 10 were French-owned. Consequently, in time of war the French had a pool of only about 50,000 skilled seamen on which to draw when the fleet was mobilized. The British had more than double that figure: the census of 1801 recorded 135,000 sailors in the Royal Navy and 144,000 in the merchant marine.

That is why the Pont d’Iéna and the Gare d’Austerlitz are in Paris but Trafalgar Square is in London. The contrast between the two combatants in the ‘Second Hundred Years War’, which began with the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and ended at Waterloo, must not be exaggerated. It was not a simple confrontation between an aristocratic French state based on land and a bourgeois British state based on commercial capital. After 1629 French nobles were permitted to engage in ship-owning and overseas commerce, and after 1701 in any form of wholesale trade, without losing their noble status by derogation. Many of them did so. The French historian Guy Chaussinand-Nogaret has written: ‘from 1770 onwards…the nobility began to be massively involved in great overseas trading companies, which they sometimes founded’. The West Africa Company, founded in 1774 to open up the colony of Cayenne and to supply it with slaves, numbered among its twenty-four shareholders the duc de Duras, the marquis de Saisseval, the comte de Jumilhac, the abbot of Chartreuve, the comte de Fresserville, the marquis de Mesnilglaise, the marquise de Grignon, the comte de Blagny and the marquis de Rochedragon. On the other hand, the British Parliament was still dominated by landowners in 1815. The British peerage admitted no merchant or financier to its ranks during this period. In the view of John Cannon, the aristocrats who ran the country constituted ‘one of the most exclusive ruling elites in human history’.

Yet there were important differences. The French seat of government was at Versailles, a wholly artificial creation, built on a greenfield site at the behest of a single individual. The British capital was London, a great port and financial centre. If the importance of its court has sometimes been underestimated, it did not compare with the size, grandeur and prestige of its French counterpart. As we shall see in a later chapter, London was also the centre of a rapidly growing public sphere, in which commercial interests could be articulated and applied. As so often, the ‘primacy of foreign policy’ had a part to play. The accession of a Dutch king in 1688 created the concept of ‘the Maritime Powers’, a natural alliance bound together by a common commitment to defending liberty, Protestantism and commerce against the absolutism and Catholicism of France. The checking of Louis XIV’s ambitions in the 1690s and the victories of the War of the Spanish Succession appeared to prove that the balance of power in the world had swung the Anglo-Dutch way, especially to the Anglo part. Daniel Defoe claimed in The Complete English Tradesman of 1726, ‘We are not only a trading country, but the greatest trading country in the world.’ He added, perhaps more controversially, ‘our climate is the most agreeable climate in the world to live in’. This triumphalist theme was reprised constantly. Edward Young, better known as the author of Night Thoughts, crowed in 1730 that the world conspired to make England rich:

Luxuriant Isle! What Tide that flows,

Or Stream that glides, or Wind that blows,

Or genial Sun that shines, or Show’r that pours,

But flows, glides, breathes, shines, pours for Thee?

How every Heart dilates to see

Each Land’s each Season blending on thy Shores?

…

Others may traffick as they please;

Britain, fair Daughter of the Seas,

Is born for Trade; to plough her field, the Wave;

And reap the growth of every Coast:

A Speck of Land! but let her boast,

Gods gave the World, when they the Waters gave.

Britain! behold the World’s wide face;

Not cover’d half with solid space,

Three parts are Fluid; Empire of the Sea!

And why? for Commerce. Ocean streams

For that, thro’ all his various names:

And, if for Commerce, Ocean flows for Thee.

It was a vision shared ten years later, in 1740, by the hermit in Thomson’s Alfred in his final exhortation to the beleaguered Saxon king:

I see thy commerce, Britain, grasp the world:

All nations serve thee; every foreign flood,

Subjected pays its tribute to the Thames.

As the British saw it, their four great mutually supportive achievements–power, prosperity, Protestantism and liberty–were all secured by commerce, so the merchant enjoyed a correspondingly high status. In 1722 Richard Steele put the following words into the mouth of Mr Sealand in his play The Conscious Lovers: ‘I know the Town and the World–and give me leave to say, that we Merchants are a species of Gentry, that have grown into the World this last Century, and are as honourable, and almost as useful, as you landed Folks, that have always thought yourselves so much above us.’ John Gay was more forceful in The Distress’d Wife: ‘Is the name then [of merchant] of Reproach?–Where is the Profession that is so honourable?–What is it that supports every Individual of our Country?–‘Tis Commerce–On what depends the Glory, the Credit, the Power of the Nation?–On Commerce.–To what does the Crown itself owe its Splendor and Dignity?–To Commerce.’ Daniel Defoe agreed: ‘trade in England makes Gentlemen, and has peopled this nation with Gentlemen’. To these literary examples can be added the authoritative opinion of a Swiss traveller, César de Saussure, who observed in 1727: ‘In England commerce is not looked down upon as being derogatory, as it is in France and Germany. Here men of good family and even of rank may become merchants without losing caste. I have heard of younger Sons of peers, whose families have been reduced to poverty through the habits of extravagance and dissipation of an elder son, retrieve the fallen fortunes of their house by becoming merchants.’ In the past it had been an axiom of English political theory that a virtuous polity depended on a tradition of civic humanism, sustained by a landed elite whose independence ensured their virtue. Now there emerged a greater willingness to view commercial society, not as a sink of corruption but as a wholly legitimate sphere of private sociability.

Ultimately it is this question of status that distinguishes British from French commerce in the period 1660–1815. In France it was certainly important, but was never more than one course on a rich menu of national attributes. In Great Britain it was paramount. The speed of the country’s commercial success was such as to catch the eye of a wide range of observers unconnected with–and unsympathetic to–trade. Horace Walpole, forth Earl of Orford, told his correspondent Horace Mann: ‘You would not know your country again. You left it as a private island living upon its means. You would find it the capital of the world.’ That arch-Tory Dr Johnson recognized that ‘there was never from the earliest ages a time in which trade so much engaged the attention of mankind, or commercial gain was sought with such general emulation’. It also excited plenty of adverse comment, from John Brown, for example, who in 1758 wrote an eighty-page rant–An Estimate of the Manners and Principles of the Times–to show that excessive trade, and the wealth that flowed from it, had brought effeminacy, irreligion and decadence. Behind these subjective impressions lay some impressive statistics, for example that the merchant marine almost trebled from 3,300 vessels (260,000 tons) in 1702 to 9,400 (695,000 tons) in 1776; that imports increased from c. £6,000,000 of goods in 1700 to c. £12,200,000 in 1770; and that exports in the same period more than doubled from £6,470,000 to £14,300,000. If these men had lived until the end of the century, they would have had even greater occasion for celebration or deprecation. As Cain and Hopkins have established, over the whole period 1697–1800 exports from England and Wales grew at a mean rate of 1.5 per cent per annum. However, in the 1780s, when cotton manufactures took off, really impressive acceleration occurred, achieving a rate of 5.1 per cent per annum for the period 1780–1800. Exports’ share of national income rose significantly to reach 18 per cent by 1801, having doubled since 1783. If Joseph Palmer, whose admiration of the splendour of Bordeaux was quoted at the beginning of the chapter, had been able to visit London in 1818, he would have found 4 miles (6.5 km) of dockyards, 1,100 ships, 3,000 barges, 3,000 watermen or navigators, 4,000 dockers and–as a depressing final touch –12,000 revenue officers. By this time, the city had become a gigantic entrepôt, making England not just the workshop but also the warehouse of the world (Boyd Hilton).

THE RESIDENTIAL CITY

Change caught the eye of contemporaries, and change has caught the eye of historians. The modernizing vigour of commercial centres such as London and Liverpool, Nantes and Bordeaux, Hamburg and Danzig, St Petersburg and Sevastopol, made them seem like the cities of the future. And so they were. Yet for most townspeople, it was not the merchant who provided their livelihood. The characteristic urban economy of the period 1660–1815 was not a port but a court. This was the golden age of the Residenzstadt, the ‘residential city’ whose raison d’être was provided by those who resided within its walls: the ruler, his officials, his clergy and his courtiers. Together these privileged groups formed a powerful economic group, spending in the city what they extracted from the countryside in the form of taxes, rents and seigneurial dues. It was the compulsory sacrifices of the peasants that allowed the Residenzstadt to flourish. In the post-industrial world, domestic service has been marginalized if not eliminated, but in early modern Europe it was the prime source of urban employment. One example must suffice: in his social survey of Vienna conducted in the late 1780s, Joseph Pezzl identified at least a dozen ‘princely’ establishments, that is to say households maintained by magnates with the title of Prince (Fürst). The richest of them–the Liechtensteins, Esterházys, Schwarzenbergs, Dietrichsteins and Lobkowitzes–each put between 300,000 and 700,000 gulden into circulation every year. Below this elite came around seventy Counts (Grafen), spending between 50,000 and 80,000 gulden and then fifty or so Barons (Freiherren) whose households disbursed between 20,000 and 50,000 gulden. It was from the middle group of Counts that Pezzl took a representative establishment to illustrate why the city teemed with servants:

The lady of the house needs for her service one or two chambermaids, a man servant, a washerwoman, two parlourmaids, an extra girl, a porter, a messenger and two general servants.

The man of the house has a secretary, two valets de chambre, a lackey, huntsmen, messengers, footmen, two general servants.

For the general service of the house there are a major domo, a waiter, two charwomen, two house-boys and a porter or gatekeeper.

In the kitchen there are a chef, a confectioner, a pastry-cook, a roasts-cook, plus the usual crowd of kitchen-boys, kitchen-porters, washers-up, scullery-maids etc.

The stables are looked after by a master of the horses, a riding-master, two coach-men, two postillions, two outriders, two grooms, four stable lads etc.

This was a culture in which status counted for everything, display determined status, and display could be sustained only by an ‘appropriate’ establishment. So Pezzl could add: ‘the total number of male and female domestic servants in Vienna is estimated to be 20,000 and this estimate is certainly not exaggerated’. At the time he wrote, the total population of the city was about 225,000. Apart from these direct dependants, almost everyone engaged in trade, retailing or manufacturing was part of the Residenzstadt nexus. The conspicuous consumption of the privileged orders created an economy in their own image, a web of luxury trades and luxury services which drew to Vienna the labour to serve them. As the author of another contemporary survey, Ignaz de Luca, recorded: ‘The great majority of the nobility in the city are courtiers or civil servants. Taken as a whole, the nobility owns great wealth and spends freely, which is a blessing for the working population, especially in a place like Vienna where there is a large number of manufacturers, artisans and other labourers.’ David Hume’s sour comment in 1768 was that the city was ‘compos’d entirely of nobility, and of lackeys, soldiers and priests’.

Even the very first cities to be formed, in the river valley civilizations of the near east, were sustained in part by the residence of a rentier class ‘living off its rents’. What was special about our period was the dominant role this element exercised in so many parts of Europe. Partly this was due to a new geographical stability on the part of the courts, which by the end of the seventeenth century had ceased to be peripatetic. One weary ambassador to the court of the French King Francis I (1515–47) had complained that ‘never during the whole of my embassy was the court in the same place for fifteen consecutive days’. Under Louis XIV (1643–1715), the court came to rest at Versailles and quickly turned a greenfield site into a Residenzstadt, the tenth largest city in the country. Vienna did not become the permanent capital of the Habsburg Monarchy until the reign of the Emperor Ferdinand II (1617–37) and could only turn itself from frontier fortress into Residenzstadt when the threat from the Turks was finally lifted following their abortive siege of 1683. The subsequent construction of such monumental buildings as the Church of St Charles (Karlskirche) or Prince Eugene’s summer palace, the ‘Belvedere’, outside the old fortifications advertised the confidence of the ruling orders that the Turks would never be a threat again. By 1720 no fewer than 200 palaces of various kinds had been built in and around the city, doubling by 1740. Now the city came to be known as the Habsburg Monarchy’s ‘Capital-and Residential-City’ (Haupt-und Residenzstadt).

At the centre of these residential cities stood the court, the interface between princely power and aristocratic privilege. It was a place of ‘representation’, where the authority of the ruler was made visible through display and ceremony; it was a place of recreation, where high society could dine, dance, gamble, attend balls, operas and ballets and generally have a good time; it was a place of negotiation where deals between centre and periphery, capital and province could be brokered. It was a place of conflict, and a place of conflict-resolution. No longer did the great landowning magnates of Europe seek to challenge the monarch by building alternative power-centres on their estates. The English Wars of the Roses (1457–87), the French Frondes (1638–43), the Thirty Years War (1618–48), and the Hungarian rising led by Francis II Rákóczy (1703–11)–just to name a few of the more important convulsions–were all followed by a new sociopolitical alliance between ruler and privileged orders. In no case was there a simple victory of absolutism over aristocracy, however much the new court discourse elevated the royal image. To borrow the striking metaphor of John Adamson, at court ‘the carapace of authority concealed a diversity of partly complementary, partly competing “foyers of power” ’. Between the middle of the sixteenth and the end of the seventeenth century, there developed across Europe what Adamson has called a ‘standardisation of expectations’ as to what a court should comprise.

As we shall see in a later chapter, the court played a dominant role in the politics and the culture of most European countries during this period. Here it is its economic role that needs further emphasis. In particular, the sheer size of the undertaking needs to be borne in mind. As Olivier Chalines has written about Versailles: ‘far from being merely an assemblage of the higher nobility drawn in from the various provinces of the realm, it was a whole society in miniature, with its own priests, soldiers, officials, tradesmen and domestic servants’. There were 10,000 of them by the end of Louis XIV’s reign, which made his court the greatest single employer in his kingdom, with the exception of the army, itself also strongly represented at court. Moreover, around the Sun King or his equivalent there revolved many planets, each with its own subordinate moons.

Many of them wore clerical garb. Especially in Catholic countries, the Residenzstadt had a strong ecclesiastical flavour. Indeed, demonstrative piety was one of the ‘standardized expectations’ referred to above. It was at court that both individual prelates and pious institutions could catch the eye of a royal patron. Indeed, in surprisingly many cases, it was the Church that stood at the centre of the residential economy. Most obviously, this was the case in Rome, both the Holy See of St Peter’s successor and the capital of his secular patrimony. It was also the preferred place of residence for the great aristocratic families that for so long had dominated the Sacred College of Cardinals, and with it the Pontificate, as the names of the most prominent palazzi demonstrate: Altieri, Borghese, Chigi, Colonna, Este, Farnese, Fiano, Pamphili, Ruspoli, Sciarra, and so on. Virtually every Catholic religious order felt obliged to maintain a branch there, with the result that there were 240 monasteries for males and 73 convents for females. Together they owned about a third of the city’s real estate and, together with the secular clergy, comprised about 7 per cent of the total population of 140,000 in 1740.

Rome also boasted two other assets that brought visitors flocking from all over Europe to reside within its walls, however briefly. The first was its status as capital of the Catholic Christian world. If less obligatory than the Muslim haj, a pilgrimage to Rome and its innumerable churches and relics had a powerful appeal to the faithful, especially during a jubilee year. In 1650,700,000 are reported to have made the journey. They were a few years too early for Bernini’s great colonnade enclosing St Peter’s Square, which could accommodate 100,000 pilgrims at a time. The second asset was the new fashion for old artefacts. For the thousands of wealthy Europeans who set out each year to explore the continent’s cultural riches, a visit to the sites of classical antiquity, and especially Rome, was the sine qua non. As Dr Samuel Johnson observed: ‘Sir, a man who has not been in Italy is always conscious of an inferiority, from his not having seen what it is expected a man should see. The grand object of travelling is to see the shores of the Mediterranean’, for ‘all our religion, all our arts, almost all that sets us above savages, has come from the shores of the Mediterranean.’ Now that it was so much safer and easier to travel, it became de rigueur for young men with pretensions to intellectual attainment to travel to the places they had studied so intensively in the course of their mainly classical education. No one put this better than Joseph Spence, accompanying the Earl of Middlesex in 1732:

This is one of the pleasures of being at Rome, that you are continually seeing the very place and spot of ground where some great thing or other was done, which one has so often admired before in reading their history. This is the place where Julius Caesar was stabbed by Brutus; at the foot of that statue he fell and gave his last groan; here stood Manlius to defend the Capitol against the Gauls; and there afterwards was he flung down that rock for endeavouring to make himself the tyrant of his country.

If the pious pilgrims still had the numerical advantage, it was the secular tourists, especially the notoriously wealthy and gullible British, who packed the purchasing power. They also flocked to Venice. The beauty of the latter’s setting and architecture, its reputation for sexual license, especially during the Carnival season, and the high quality of its public entertainment, notably opera, combined to attract high-spending visitors from all over Europe.

At the other end of the hedonistic scale was a special sub-category of residential cities in which the military predominated. Unquestioned leader here was Berlin, where every visitor was struck by the ubiquity of men in uniform. When Frederick the Great came to the throne in 1740, the city had a civilian population of 68,961 and a garrison totalling 21,309, including dependants. By the time he died in 1786, the city was surrounded by barracks ‘like a necklace’, as one observer commented, and those figures had risen to 113,763 and 33,635 respectively. Not far behind came St Petersburg, which in 1789 included 55,600 soldiers and their families among its population of 218,000.

Great cities such as Vienna, Rome, Venice or St Petersburg were the most conspicuous examples of the importance of the residential economy, but in aggregate terms they were eclipsed by the numerous smaller versions spread across Europe. The region par excellence of the residential city was the Holy Roman Empire, that loose amalgam of princes, both secular and ecclesiastical, and Free Imperial Cities subject only to the nominal authority of the Emperor. Whatever their exact title (and there was a rich variety), every ruler held sway over a court and capital. Some were very small–Weimar, for example, home to Goethe, Herder, Wieland and many other luminaries, had a population of only about 7,000 at the end of the eighteenth century. Only two were really large cities by the standards of the age–Berlin with 175,000 and Vienna with 225,000. What they all had in common was economic dependence on the ruler. A good example of a middling Residenzstadt was Mainz, capital of the eponymous Archbishop-Elector, with a population of about 30,000 in the 1780s. About a quarter of this number were nobles, clergymen, officials and government employees of one kind or another, and their dependants. The Elector also exercised considerable indirect influence on the economy through his expenditure. The court needed food, drink and entertainment; the Electoral palaces and government buildings had to be maintained; the various offices of state needed a thousand different commodities. The economic importance of the court, nobility and clergy was demonstrated clearly when they departed in the wake of the wave of French invasions beginning in 1792. The population fell by a third to just over 20,000, despite Mainz becoming an important French garrison town and the capital of the Mont Tonnerre département. The missing thousands had followed their sources of livelihood into exile at the courts of Franconia and Bavaria.

It was not only royal or princely capitals which housed a residential sector. Every town which attracted rentiers to reside within its walls was to a greater or lesser extent a Residenzstadt. This applied to spas such as Bath or Bad Pyrmont, to provincial centres such as Toulouse or Kiev, and to ecclesiastical centres such as Valladolid or Angers. No wonder that Angers was a centre of counter-revolution after 1789. When the town was captured by the Vendéan insurgents in 1793, a local priest found a receptive congregation when he preached on the beneficence of the clergy, claiming they ‘received with one hand to give with the other. They were the beneficent syphon which drew up the water, distributed it and fertilized the land…The clergy were almsgiving itself. Their property belonged to the people.’ In trying to explain why the French Revolution attracted such widespread hostility from the common people, both inside and outside France, historians would do well to look beyond social divisions, or even ideology and culture, to hard-nosed economic interest.

MANUFACTURING

Perceptions of that interest were strongly influenced, if not dictated, by what continued to be the most common form of organization for manufacturers–the craft guild. Its longevity was due not least to the plurality of tasks it performed: quality control, social disciplining, social welfare, status maintenance, religious devotion and collective recreation being just a few. At its heart, of course, stood its monopoly of production of a given commodity in a particular community. In most European towns for most of the eighteenth century, aspiring manufacturers had to join a guild. Typically, the trainee craftsman first had to serve an apprenticeship of three years. As a journeyman, he then left the city to travel from one town to another, collecting en route testimonials from his various employers. This peregrination usually lasted at least two years. On his return to his home-town he was not allowed to apply immediately for admission to the ranks of the masters. First he had to work for another two years or so as a simple journeyman. He was then permitted to submit his masterpiece to the guild and, if it were approved, to pay the substantial fees and become a master. This is a very generalized account; the process was often very much longer or, especially if the candidate concerned were a close relation of an existing master, shorter. Needless to say, this long and complicated procedure gave the guilds ample opportunity to keep their numbers down, the regulations governing the presentation of masterpieces being an especially potent weapon.

Like so many other organizations enjoying a monopoly of their chosen activity, the craft guilds had a built-in tendency towards ossification. By the eighteenth century many were showing all the negative conservatism of a vested interest overtaken by events: dogged devotion to old techniques, suspicion of innovation, resentment of competition and xenophobia. They were particularly determined to confine guild membership to ‘their kind of people’. The early modern value-system prioritized honour and the guild-masters were just as determined to defend their place in the social hierarchy as was any magnate or prelate. So no applicant for admission to a guild need bother unless male, of legitimate birth and of the right religious denomination. Contamination by contact with a ‘dishonourable profession’ offered a rich range of reasons for the exclusion, for example, of sons of public executioners, knackermen, tanners, barber-surgeons, shepherds, musicians, actors, pedlars or beggars. More bizarrely, in Germany at least, the offspring of civil servants were ruled out. Significantly, so were factory-workers. The pedantry displayed when enforcing these regulations may well have concealed a more personal vindictive agenda. In 1725 in Brandenburg, for example, a cloth-maker was ejected from his guild when it came to light that his wife’s grandmother was allegedly descended from a shepherd. A cobbler spotted drinking with the local hangman suffered the same fate.

More serious than these occasional acts of discrimination was the dead weight constantly applied to enterprise and innovation, as the master craftsmen protected their monopoly by reducing competition to a minimum. In France it was the requirement of a masterpiece that was exploited most. The journeyman was often required to produce a fiendishly complicated piece of work, to give presents to the jury members appointed to assess its merits, and then, if successful, to pay an entrance fee to the guild. In Paris, the distillers required 800 livres and the apothecaries 1,000 livres. Yet the sons and grandsons of existing masters were often exempted from some or even all these requirements. Minutely detailed regulations on size and quality choked innovation and adaptation to changing market conditions. The new code introduced in the Dauphiné in 1782, for example, contained 265 paragraphs. New commodities were seen not as an opportunity but as a threat, as in the case of printed calicoes, banned by a series of ordinances passed between 1686 and 1759. Typical was the attitude expressed by the town council of Strasbourg in 1770 when obstructing an attempt by a cotton manufacturer to get established: ‘it would upset all order in trade if the manufacturer were to become merchant at the same time, and infringe the most sensible rules laying down who are allowed to trade in the city’. These and many other abuses were recounted with relish by the enlightened reformer Turgot, when he proposed to Louis XVI in 1776 that the guilds be abolished outright. The excessive demands for useless and expensive masterpieces, he argued, were forcing gifted craftsmen to leave France to work abroad. The guilds’ arguments that they ensured quality control he dismissed as spurious: ‘liberty of trades has never caused ill effects in those places where it has been established for a long while. The workers in the suburbs and in other fortunate places do not work less well than those living in Paris. All the world knows that that the inspection system of the guilds is entirely illusory.’ He concluded: ‘I regard the destruction of the guilds, Sire, as one of the greatest benefits that you can bestow on your people.’ Turgot fell from power, following a court intrigue, before the necessary legislation could be enforced. It was left to the Revolution to complete his work.

Other governments took frequent action against guild abuses. In the Holy Roman Empire the Imperial Trades Edict of 1731 offered both a comprehensive indictment and a programme for reform. Some idea of the pre-modern world in which the guilds operated can be gained from paragraph number one of article thirteen:

That the tanners and the tawers [Rothgerber and Weissgerber, two tanning trades using different materials and techniques] in some places brawl with one another over the processing of dog skins, and over other useless disagreements among themselves, and those who will not process them call the others dishonourable, and also will have it that apprentices who have worked in places like that should be punished by the others. Similarly if an artisan stones a dog or cat to death, or beats it, or drowns it, or even just touches a carcass, an impropriety is wrung out of that, to the point that the skinners take it upon themselves to pester such hand workers by sticking them with their knives and in other ways, and in such fashion as to oblige them to buy their way out of it with a sum of money.

Significantly, this edict was renewing previous measures dating from 1530, 1548, 1577, etc. and conceded that ‘these very salutary provisions have not altogether been lived up to and even other abuses have gradually crept in’. As implementation was conditional on action by the individual principalities of the Empire, very little was actually achieved. The guilds were so deeply entrenched in most places that any attempt to wrench them out by the roots caused social and political disorder. Especially during the difficult years of the mid-seventeenth century, rulers found themselves obliged to do deals with all manner of corporate bodies, including the guilds. Moreover, the latter showed surprising tenacity and even vitality in some trades. Far from being ‘decadent’, ‘moribund’ or ‘superannuated’–just three of the adjectives often applied to their condition in the eighteenth century–guilds were still being created. Wherever governments valued social harmony and control above productivity, the guilds could find friends. So the troubled times after 1789, and even after 1848, saw the guilds taking on a new lease of life.

As the tanners and tawers knew, there was more than one way of killing a cat, and there was more than one way of dealing with the guilds. Especially popular in continental monarchies was the granting of permission to favoured entrepreneurs to operate outside the guild system, producing certain specified–usually luxury–goods. Setting the pace here was Jean-Baptiste Colbert, who took control of economic policy in France in the 1660s. In 1662 he paid 40,000 livres for ‘a large house situated on the Faubourg Saint-Marcel les Paris, commonly known as the Gobelins’. He filled it with a number of tapestry workshops under the general direction of the painter Charles Le Brun. Before long there were working there ‘over 800 tapestry workers, sculptors, artists, goldsmiths, embroiderers and, in general, workers in all that made for splendour and magnificence’. Their first task was appropriately representational, namely creating a series of huge tapestries to designs of Le Brun illustrating Louis XIV’s exploits. To consummate the union between royal economic enterprise and royal display, one of the tapestries depicted ‘King Louis XIV visiting the Gobelins Manufactory’. Other similar enterprises followed, the largest for the production of mirrors and soap.

As we shall see in a later chapter, such was the success of the ‘Versailles project’ that most other European sovereigns felt obliged to follow the French example. Although this emulation was partly a matter of fashion, it was also driven by a mercantilist concern to improve the balance of trade by reducing expensive imports. Right across continental Europe, non-guild manufacturing establishments were founded with government support, encouraged by all kinds of fiscal and financial privileges. In the Electorate of Mainz, for example, they were set up to produce ribbon and braid, cotton, pencils, chocolate, gold and silver chain, hats, silk, surgical instruments, playing cards, sewing needles, Spanish noodles, soap, parchment, cosmetics, taffeta and chintz (and even this is not a complete list). It is next to impossible to assess the overall effect of these and similar enterprises elsewhere. Did they promote the economy by providing capital and enterprise which otherwise would have been absent? Or did they impede development by stifling competition? Certainly many of them were short-lived, bobbing from crisis to crisis, kept afloat only by further injections of capital before sinking when the bottom of the royal purse was reached. Success stories such as Meissen or Nymphenburg porcelain were rare. On the other hand, apologists for royal subsidies have pointed out that the level of subsidy was relatively low. Even Louis XIV advanced only 284,725 livres to mirror manufacturing between 1667 and 1683, and about 400,000 livres to soap manufacturing between 1665 and 1685. His total subsidy to privileged manufacturing during a twenty-year period was about 16,000,000 livres, which sounds a good deal until one recalls that the gross annual domestic product during the same period was around a billion-and-a-half livres. It also appears that many of those regions which progressed to full-blown industrialization in the nineteenth century had received privileged treatment during the eighteenth.

Although the products of these luxury industries now line the walls of palaces or fill the display cabinets of museums, at the time their impact on the larger economy was marginal. Much more subversive of guild domination of manufacturing was the expansion of rural industries, especially in the manufacturing of textiles but also of goods such as gloves, ribbons, stockings, shoes and hats, not just on a small scale for local consumption but on a mass basis for export markets. The key figure here was the merchant-capitalist, who co-ordinated the various processes on a ‘putting-out’ basis. It was he who bought the raw material and had it delivered to the homes of the labourers, first to the spinners, then to the weavers and then to the fullers and dyers who turned it into finished cloth. It was he who paid them on a ‘piecework’ basis. It was also he who found a cloth factor to take it to market. The advantages of this system were manifold: it exploited cheap rural labour, increasingly available as the population expanded; it minimized the need for fixed capital; it gave peasants the opportunity to supplement the returns from theirplotsbyworkingafterdarkorduringslackperiodsoftheagricultural year; it allowed the unskilled labour of women, children and the elderly to make a contribution to the household’s income; it promoted the division of labour; and it evaded all the rules and regulations of the guilds, especially quality controls and limits on the size of enterprises.

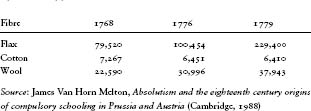

That ‘putting-out’ to rural labourers suited the needs of the age was demonstrated most eloquently by the large and rapidly rising number of those involved. In Prussian Silesia, production of linen rose from 85,000 to 125,000 pieces between 1755 and 1775 and the number of looms from 19,810 in 1748 to 28,704 in 1790, by which time there were in excess of 50,000 people employed in the industry. Table 6 shows a comparable increase in the number of flax, cotton and wool spinners in Bohemia in the space of just eleven years between 1768 and 1779.

Table 6. Increases in Bohemian textile-spinner numbers during the 1760s and 1770s

Melton also estimates that in the province of Lower Austria the number employed in manufacturing rose from 19,733 in 1762 to 94,094 in 1783. Similar figures were recorded from the many other ‘industrial landscapes’ which developed during the course of the eighteenth century, in Italy: a broad band of Lombardy in the hills north of Milan from Val d’Aosta to Lake Garda, the riviera around Genoa and Tuscany north of the Arno; in the Iberian peninsula: Catalonia, which in 1770 was described by one visitor as ‘a little England in the heart of Spain’ and by the 1790s boasted the biggest concentration of dyers and weavers outside Lancashire; in France: Brittany, Maine, Picardy and Languedoc; in the southern Netherlands: Flanders and Twente; in the Holy Roman Empire: the lower Rhine, Westphalia, Baden, Württemberg, Westphalia, Silesia and southern Saxony; in the Habsburg Monarchy: Bohemia, Moravia and Lower and Upper Austria; in England: Lancashire, the West Riding of Yorkshire, the Cotswolds and East Anglia. The number of people employed was considerable, as every weaver’s loom required around twenty-five ancillary personnel to keep it supplied, including six spinners. A good example of how putting-out could erode the position of the guilds was provided by the expansion of the bleaching industry in Elberfeld and Barmen, two adjacent towns in the Duchy of Berg on the Lower Rhine. Originally a guild monopoly, the process moved into the surrounding countryside, making best use of the river Wupper, and expanded from 15 enterprises in 1690 to 100 in 1774 and 150 in 1792. Following the inevitable tussle with the guilds, the government lifted all restrictions on production in 1762.

This summary of the development of rural manufacturing has deliberately avoided use of the contentious concept ‘proto-industrialization’. First coined in 1972, it was advanced by its supporters as an explanation for the breakthrough from traditional forms of manufacturing to the industrial revolution, being held responsible for population growth, the commercialization of agriculture, capital accumulation, the generation of surplus labour, proletarianization and the creation of large markets. Subsequent criticism has left little of all this intact. It has been argued in return that the region from which the phenomenon was first derived–Flanders–was exceptional, matched only by England and one or two other small enclaves on the continent. Sheilagh Ogilvie, the most effective critic of proto-industrialization, concludes:

In the rest of eighteenth-century Europe, proto-industry (like agriculture) was regulated by traditional institutions: guilds, merchant organisations, privileged towns, village communities, feudal landlords. The spate of research on proto-industrialisation has shown that industrial development was affected much more strongly by institutional variations than by the presence (or absence) of proto-industry.

From the point of view of the entrepreneur, the least attractive feature of putting-out was the lack of control over the workforce. The labourer worked unsupervised, at his own pace and when he felt like it. When the household’s income reached a certain point, there was a tendency to prefer leisure to labour, even if the market–and the merchant–were crying out for more goods. One answer was to concentrate production in a single centre and to move from paying piecerates to paying wages. That required higher fixed capital in the form of buildings, and consequently greater vulnerability to market fluctuations, but it did allow the workers to be supervised and kept up to their work. These ‘manufactories’ proved to be an effective way of responding to market opportunities in the eighteenth century. It has been estimated that there were about 1,000 of them in German-speaking Europe in 1800, of which 280 were in the Habsburg Monarchy (140 in Lower Austria and 90 in Bohemia), 220 in Prussia, 170 in Saxony and 150 in the Wittelsbach territories (Jülich-Berg, the Palatinate and Bavaria). Some of the individual units employed large numbers of workers on a central site: to select a few examples from the 1780s, the state-run woollen manufactory at Linz employed 102 dyers and finishers, a calico printing firm at Augsburg employed 350, the royal textile manufactory in Berlin employed c. 400. Even luxury goods could record large numbers of factory workers, with around 400 at both Meissen and Berlin in 1750. Significantly, the further east one went, the more of these large enterprises were owned and run by great aristocratic magnates, exploiting both the raw materials and the cheap serf labour to be found on their estates. The greatest single entrepreneur in the Habsburg Monarchy was Count Heinrich Franz von Rottenhan, who established two large cotton factories and an ironworks on his Bohemian estates. Although the state was directly responsible for some of the largest concerns–the Lagerhaus in Berlin, for example, which made uniforms for the Prussian army–its numerical share was only about 6 per cent. On the other hand, there were numerous private individuals who amassed great fortunes from manufacturing–Schüle the ‘calico king’ of Augsburg, the Bolongaro brothers of Frankfurt am Main (tobacco), and the von der Leyen dynasty of Krefeld (silk), for example. Nor was the centralized manufactory a phenomenon confined to north-western Europe: in 1779 in Barcelona there were nine woollen factories employing 3,000, and there were many units in Russia with workforces numbered in thousands.

AN ‘INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION’?