13. MEAT

Consuming the flesh of other animals has arguably been important to human evolution. About 2.5 million years ago, hominins started eating larger quantities of meat and marrow. Initially they used their tools to slice the meat into small, chewable pieces. At some point, they also learned to cook their meat, making it softer and easier to digest. Over time, this led to the evolution of smaller teeth and jaws and a smaller gut. Animal proteins are also calorie dense, protein rich, and chock-full of micronutrients. When your main occupation is finding food, these are all positive qualities, and this is likely why meat tastes good. Our very early ancestors probably scavenged their meat, but humans later domesticated animals that they used for milk and eggs, and occasionally butchered for meat. Today, the meat industry is huge. Although meat is popular all over the world, Americans in particular are big consumers, eating an estimated three times more meat than the global average. As a group, Americans eat more than enough meat. In some cases, we may, in fact, be eating a lethal dose of meat. Too much red meat increases the rate of all-cause mortality.

For the generations of people who were brought up to think of meat as a health food, this is a bit surprising. Doesn’t meat help you to grow up big and strong? What about all of those proteins and micronutrients that prompted our ancestors to start eating dead things in the first place? So yes, meat is a good source of some dietary requirements. Animal proteins, unlike most plant proteins, are complete. That means that they contain all of the amino acids that you need to consume all in one place. Meat is also high in iron, zinc, and some vitamins. Notably, vitamin B12 is found only in animal products (including milk and eggs), and vegans need to take B12 supplements. Eating some meat can be healthy; we run into trouble with the quantity, the type, and the way we cook our meat.

Fundamentally, there is a difference between eating the meat of mammals and eating the meat of other animals like fish and birds. The muscles of all mammals are called red meat. We also need to distinguish between processed meat and unprocessed meat. Meat processing includes salting, smoking, canning, and fermenting. Basically, anything beyond grinding or pounding is considered processing. Examples of processed meats are ham, bacon, smoked turkey, hot dogs, and beef jerky.

Processed meat is classified as a known human carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a part of the World Health Organization (WHO). This means that there is sufficient evidence from scientific studies in humans to conclude that eating processed meats causes cancer. Specifically, it causes colorectal cancer and may cause stomach cancer. There are hypotheses for why this is the case. For example, the addition of nitrates may be a factor. But there is no conclusive evidence yet. There are, of course, different ways of processing meat, and it is possible that some of these methods are safer than others. But this has not yet been determined. Eating processed meat, even a large quantity, does not increase cancer risk by that much (the relative risk is 1.18), but it isn’t negligible. So far, the WHO has not offered any guidance about how much processed meat is safe to eat, if indeed there is a safe amount.

In addition, the IARC has classified red meat as a potential human carcinogen. The data about the cancer-causing effects of red meat are not conclusive, but they are suggestive. Again, the cancer of concern is colorectal cancer, and there are no specific guidelines about how much is safe to eat. One additional note about red meat: it may matter how you cook it. Cooking over high heat, as on a grill or in a frying pan, may create more carcinogenic compounds than cooking low and slow. It is not clear, however, whether this makes a difference in overall risk. The IARC did not evaluate whether unprocessed poultry and fish were carcinogenic, so they have nothing to say about these foods for good or ill.

In addition to cancer, red meat consumption is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. These problems are particularly associated with processed red meat: another good reason to cut back on bacon.

As most people are aware, raw meat products also come with a risk of foodborne illness. Escheria coli (E. coli) commonly colonize the gut of ruminant animals (like cows), and cross-contamination during butchering can lead to tainted meat. There are many different strains of E. coli, and many of them are harmless, but some can be very nasty and even fatal. So careful handling and cooking are called for whenever raw meat is prepared. Trichinosis and toxoplasmosis are caused by parasites that are found in raw or undercooked pork. Pregnant women are advised to avoid deli meats because of the risk of contamination with Listeria. But as potentially dangerous as these diseases can be, they can all be avoided by heating meat to the proper temperature. In contrast, prion diseases, like bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, commonly called mad cow disease), cannot be killed by cooking. Prion diseases, which are degenerative and invariably fatal, are transmitted by meat contaminated with affected nervous tissue. For a while it was a hot topic, though it hasn’t received much press lately. Notably, a cow with BSE was identified through routine surveillance in Alabama in July 2017.

In addition to the immediate personal health concerns that are tied to meat consumption, there are some secondary issues. For example, animals raised for meat are a known reservoir for novel viruses like new strains of influenza (swine flu, avian flu) and the shockingly lethal Nipah virus. Many meat animals are also dosed with antibiotics, both to prevent illness and to accelerate weight gain. This practice is one of the greatest contributors to the emergence of superbugs—strains of bacteria that are immune to one or more antibiotics.

But wait, there’s more. Raising animals for food is massively inefficient compared to raising food crops in terms of both land and water usage. This makes meat very expensive and contributes to global food inequity and insecurity. Animals also produce greenhouse gases, which are, of course, implicated in global warming.

If you’ve been keeping track, you will have noticed that there are quite a few good reasons to cut back on your meat consumption, especially processed meats. Fortunately, our modern food supply leaves us with many good alternatives including beans, peas, nuts, seeds, quinoa, amaranth, and lots of vegetables. Try to substitute poultry, eggs, or fish for red meat, and eat smaller portion sizes when you do indulge. If you really like processed meat, save it for special occasions, and live a little.

SUMMARY

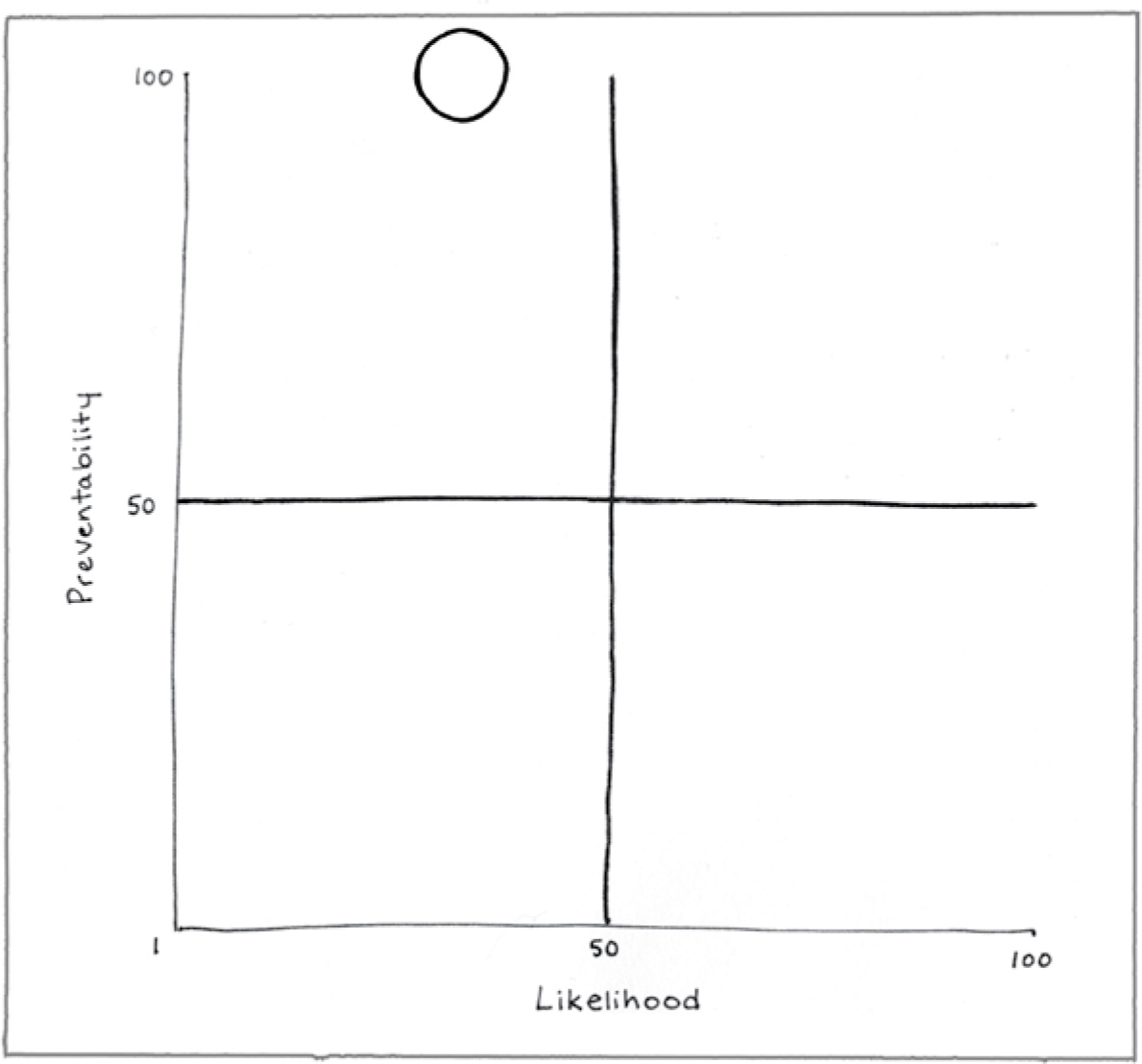

Preventability (100)

Many people (vegetarians, vegans) abstain from eating meat entirely.

Likelihood (33)

Eating red and/or processed meat slightly increases the risk of some cancers, and eating processed meat is also a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Other risks include foodborne illness, emerging diseases, and environmental impact.

Consequence (71)

None of the potential consequences are insignificant, but they do not rise to the level of certain death.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2014, March 20). Nipah virus (NiV). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/vhf/nipah/index.html

Domingo, J. L., & Nadal, M. (2017). Carcinogenicity of consumption of red meat and processed meat: A review of scientific news since the IARC decision. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 105, 256–261.

Larsson, S. C., & Orsini, N. (2014). Red meat and processed meat consumption and all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 179, 282–289.

Micha, R., Michas, G., & Mozaffarian, D. (2012). Unprocessed red and processed meats and risk of coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes—an updated review of the evidence. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 14, 515–524.

National Institutes of Health. (2012, March 26). Risk in red meat? NIH Research Matters. Retrieved from https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/risk-red-meat

Pobiner, B. (2013). Evidence for meat-eating by early humans. Nature Education Knowledge, 4(6), 1.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2017, July 18). USDA detects a case of atypical bovine spongiform encephalopathy in Alabama. Retrieved from https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/newsroom/stakeholder-info/sa_by_date/sa-2017/sa-07/bse-alabama

Wade, L. (2016, March 9). How sliced meat drove human evolution. Science. Retrieved from http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/03/how-sliced-meat-drove-human-evolution

World Health Organization. (2015, October). Q&A on the carcinogenicity of the consumption of red meat and processed meat. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/features/qa/cancer-red-meat/en/