14. FOOD SAFETY

When you sit down for a meal, you are probably thinking about how it will taste, how it will stop you from being hungry, and possibly how it will affect your waistline or your cardiovascular health. Eating is routine; unless you are getting a questionable-looking hot dog from a street vendor, you probably don’t worry that the food you are about to eat may make you sick. Because surely someone has ensured that the food you are about to eat is safe. There is nothing to worry about, is there?

Food can get contaminated by pesticides, bacteria, and viruses in many steps before it arrives on your plate. First, farms must grow food, and they may use pesticides and fertilizers to improve crop yield. Factories that subsequently sort or process food may introduce pathogens and other contaminants when products are prepared and packaged. Food products are then distributed to warehouses, stores, and restaurants. If some foods are not refrigerated properly, they can become contaminated with bacteria or mold. Finally, food must be prepared so it is ready to eat. If utensils used to prepare raw meat are not cleaned properly, they can contaminate other food such as fruits and vegetables. Some products, such as chicken, pork, beef, and fish, must be cooked thoroughly to eliminate harmful pathogens. Many people handle your food on its way to you (e.g., farmers, pickers, packers, cooks, servers), and if any of them are sick, they can infect the food you eat. Indeed, some viruses that cause respiratory illnesses can survive on fruit and vegetables for several days.

Most countries have agencies to safeguard the food supply, but regulations differ from country to country, and enforcement and inspection mechanisms are not are always followed. Contamination is not only an issue for the domestic food supply because it can also affect food that is imported from other countries. In the United States, the governmental agencies primarily responsible for keeping food safe are the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). The USDA is responsible for ensuring that meat, poultry, and egg products are safe and that these foods are labeled and packaged properly. Within the USDA, the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) is authorized by the U.S. Congress to inspect all meat, poultry, and egg products. To reduce the risk of foodborne illness, the FSIS inspects factories to ensure that companies follow food safety practices. The FDA regulates food products (domestic and imported) that the USDA does not cover such as seafood, fruits, vegetables, bread, cereal, dairy products, dietary supplements, bottled water, and food additives.

Even with these large governmental agencies monitoring and inspecting the food supply, the large number of manufacturers and huge quantities of food that require examination are a burden. It is impossible to inspect everything, and, therefore, foodborne illness is a serious public health concern. Knowing that in the United States one in six people gets sick, 128,000 people are hospitalized, and 3,000 people die each year from eating contaminated food, you might think twice before sinking your teeth into that juicy hamburger. The CDC lists more than 30 different microorganisms that can cause foodborne illness. In the United States, the pathogens most likely to cause trouble are norovirus, Salmonella, Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter, and Staphylococcus aureus. Less common but more serious foodborne illnesses are caused by Clostridium botulinum, Listeria, Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli (E. coli) O157, and Vibrio. When the USDA or FDA find contaminated products or discover an outbreak of a foodborne disease, they issue recalls and alerts to notify the public.

Common symptoms of these foodborne illnesses are gastrointestinal problems such as an upset stomach, diarrhea, cramps, vomiting, and nausea. Depending on the pathogen causing the illness, symptoms may first appear from a few hours to several days after exposure. Many people experience only mild discomfort and recover, but others develop severe symptoms that require hospitalization. E. coli bacteria infections, for example, can produce toxic chemicals that can damage the kidneys. Salmonella and Campylobacter infections can cause chronic arthritis, and Listeria infections can result in neurological disorders. Listeria is a pathogen of particular concern to pregnant women since the bacteria can cross the placental barrier, sometimes leading to preterm birth, stillbirth, or miscarriage.

In addition to microbes that cause foodborne illness, pesticides that remain on foods may also pose health risks to consumers. Many different types of pesticides are used during food production to control insects, rodents, fungi, weeds, and bacteria. Although the U.S. Environmental Protect Agency (EPA) approves pesticides for specific uses and establishes the maximum level of pesticide that can remain on food, the FDA and FSIS are responsible for enforcing the limits on approximately 700 pesticides that may be found on products that they oversee. Foods found in violation of the guidelines can be seized or, in the case of food from outside the country, refused entry.

Pesticides can improve the yield of a crop or prevent a product from becoming infected with a pest. But people can ingest pesticides when they eat food with pesticide residues. Some pesticides used in food production are carcinogenic, neurotoxic, or endocrine disruptors. The EPA sets limits on the amount of pesticide residue that can remain on food based on what its research shows to be safe. Some critics argue that the EPA data are not complete and that the long-term effects of pesticide exposure and the effects of pesticides on developing children are not adequately known. Eating organic will not help you avoid all pesticides because organic food is not necessary pesticide free. Many organic farmers still use pesticides on their crops, but the chemicals are usually not synthetic.

In addition to allowing pesticides (within limits), the FDA also allows insect parts, rodent hair, and maggots into food, within limits, of course. For example, 30 or more insect fragments per 100 grams of peanut butter, two or more maggots per 500 grams of canned tomatoes, and 11 rodent hairs per 25 grams of ground paprika are necessary before the FDA will take action. These levels have been determined to be natural or unavoidable, and while eating food contaminated with these extras is disgusting, it should not pose any health problems to people.

While we have government agencies trying to protect the food supply, there are some simple steps we can all take to reduce the risk of eating contaminated food. First, wash your hands and any cutting surfaces before and after you handle any food. Also, wash all fruits and vegetables before cutting and serving them to remove microorganisms that might contaminate the skin. To avoid cross-contamination, make sure that raw meat, poultry, seafood, and their juices stay away from food that will not be cooked. When meat, poultry, and seafood are cooked, ensure that they are heated to the proper internal temperature to kill pathogens. If you are unsure when food reaches the proper temperature, use a cooking thermometer to remove any guesswork. When you are finished with your delicious meal, get all of the leftovers into the refrigerator to slow the growth of bacteria.

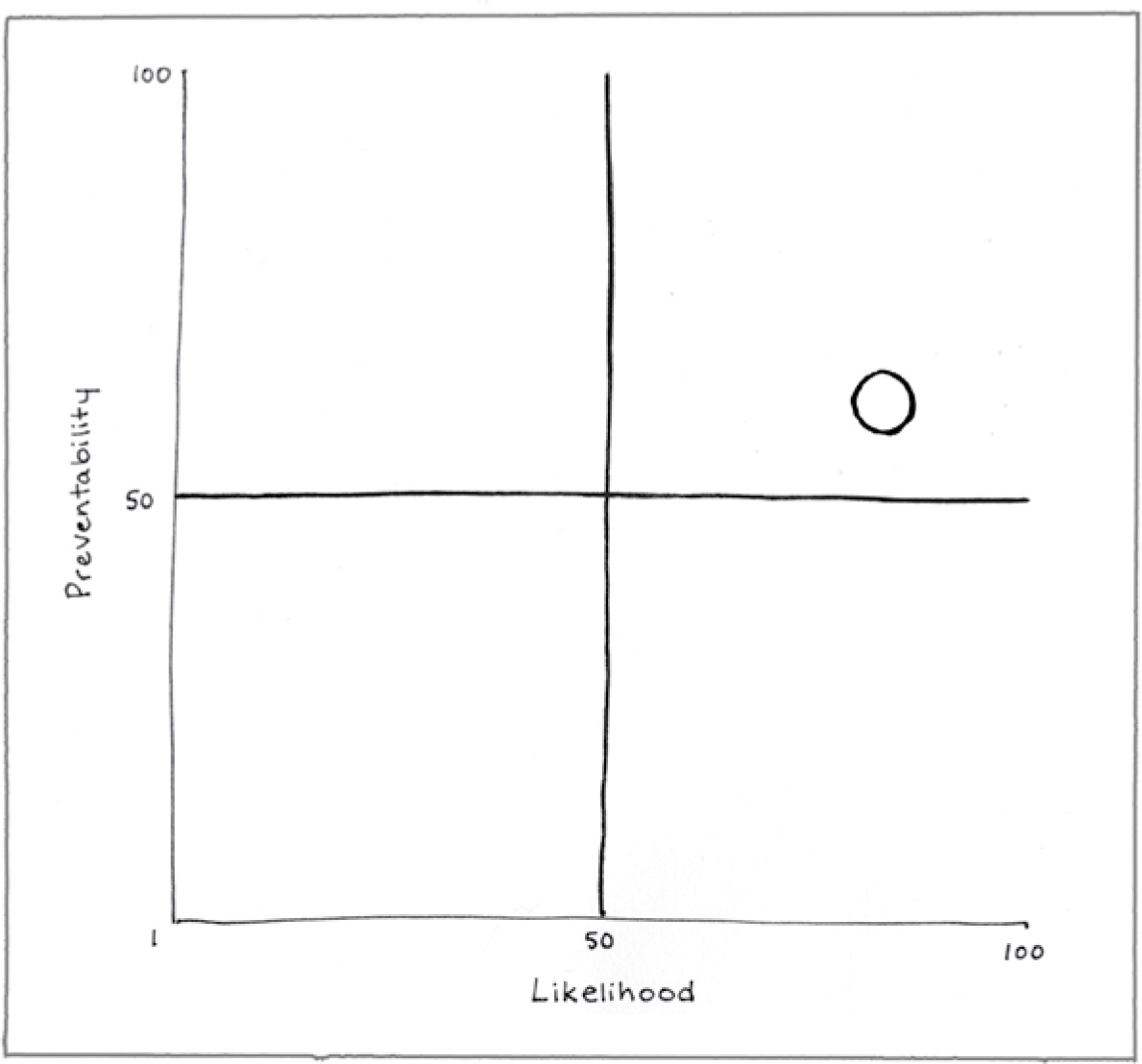

Preventability (61)

Everyone should take steps to keep their own food preparation areas clean and safe. However, if you eat out at a restaurant, you are trusting cooks and servers to provide you with uncontaminated food.

Likelihood (83)

Foodborne illnesses are very common.

Consequence (48)

The result of a foodborne illness depends on the agent causing the disorder. Symptoms range from mild gastrointestinal discomfort to infections that require a stay in the hospital.

CDC. (2016, July 15). Burden of foodborne illness: Findings. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/foodborneburden/2011-foodborne-estimates.html

CDC. (2017, December 12). Food safety. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/index.html

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2017). Defect levels handbook. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/Food/GuidanceRegulation/GuidanceDocumentsRegulatoryInformation/SanitationTransportation/ucm056174.htm

Yépiz-Gómez, M. S., Gerba, C. P., & Bright, K. R. (2013). Survival of respiratory viruses on fresh produce. Food and Environmental Virology, 5, 150–156.