18. GIVING BIRTH IN A HOSPITAL

Some people have very strong feelings about childbirth. If you think about it, you can see why. Giving birth is a life-altering event for at least two people. It is a profoundly emotional experience involving one of nature’s most powerful physiological bonds. As anyone who has ever done it can tell you, giving birth is difficult. All mammals give birth to live young (you can’t be a mammal if you don’t), but it is especially difficult for humans because of our big brains. In addition to being painful and exhausting, having a baby can be dangerous for both the mother and the baby.

Most women in the U.S. give birth in hospitals, but a growing number are choosing to have their babies in birth centers or at home. Sometimes the reasons for this are emotional; women want to welcome their children into their own homes surrounded by the people that they love. But there are often concerns about the over-medicalization of childbirth. Some people are worried that if they go to the hospital, they will be more likely to receive medical interventions, such as assisted delivery or caesarean delivery (C-section), when they don’t really need them. This perspective was championed by the 2008 documentary The Business of Being Born, which has been very influential in some circles.

Some physicians and scientists have expressed alarm and dismay at this trend, which they believe puts both mothers and babies at grave risk, even when the pregnancy is otherwise low risk. The problem, they claim, is that a routine birth can turn into a medical emergency in a very short time frame. In other words, having a baby isn’t a medical event until it is. If you are in the hospital when this happens, you can get help within minutes. If you are at home, the extra minutes that it takes to get to the hospital can mean brain damage or even death.

The points made on both sides of this argument are correct. Therefore, when you ask whether it is safer to have a baby in the hospital or at home, a lot of the answer is going to depend on what you mean by safe.

In 1915, the infant mortality rate in the U.S. was about 10% and the maternal mortality rate was about 9%. By 1997, these rates had dropped 90% and 99% respectively, prompting the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to name healthier mothers and babies as one of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century. The CIA (yes, the Central Intelligence Agency) estimates that the infant mortality rate in the U.S. in 2016 was 0.0058, or 5.8 deaths per 1,000 births. So having a baby in the U.S. is fairly safe. It is true that home births are associated with more negative outcomes for the baby. According to a 2015 report by Snowden et al. (“Planned Out-of-Hospital Birth and Birth Outcomes”), the odds of perinatal death (just before or just after birth) were 2.43 times higher for births that were planned to be out of hospital (some women transfer to the hospital when they have complications). In addition, babies born at home were 3.6 times as likely to have neonatal seizures. It is important to keep in mind, however, that the absolute number of adverse events was low, corresponding to 2.1 additional perinatal deaths per 1,000 births. This corroborates the findings of other studies, although the value of the increased risk has varied between studies.

On the other hand, the study also found that women who give birth at home were 5.63 times more likely to have an unassisted vaginal birth and women who gave birth in the hospital were 5.55 times more likely to have a C-section. These procedures are common enough now that they don’t seem like a big deal, but a C-section is still a major surgery, and that implies a certain level of risk in and of itself. This is not to mention that taking care of an infant, and potentially that infant’s older siblings, while recovering from surgery is the pits. Having a C-section also increases a woman’s chances of delivering future children in the same way, and repeating the surgery over and over compounds the risk. In addition, scientists are just beginning to understand that children also benefit from being born naturally. Children who are born vaginally acquire a microbiome from their mothers that helps develop their immune systems. C-section deliveries are associated with an increased risk of obesity, asthma, allergies, and immune deficiencies for the child. A study published in Nature Medicine in 2016 suggests it may be possible to partially restore this maternal microbial contribution to children delivered by C-section, but the jury is still out on the long-term health effects for the baby.

So when it comes to choosing the safest place to have a baby, it really depends on how you weigh the absolute and relative risks. There are steps a mother can take to mitigate overall risk no matter where she chooses to have her baby. If the decision is to plan a home birth, it is imperative to make sure that a qualified, licensed midwife is in attendance. A woman needs to verify with her doctor that she is a good candidate for home delivery, and she should have a hospital transfer plan. If the decision is to deliver in a hospital, a woman should make sure to communicate with her doctor beforehand about what is important to her. Every woman, regardless of where she chooses to give birth, should make a birth plan and share it with her healthcare provider. Some physicians and some hospitals will be more accommodating than others, so before making a decision, women should do some research and examine all of their options. In many places it is possible to have a baby delivered by a midwife in the hospital. Remember that patients always have the right to decline medical interventions, even in the hospital. Women should bring someone (a spouse, friend, parent, or doula) who is designated and prepared to act as their advocate, and they should insist that they are always informed.

Ultimately, the most important part of a birth experience is that the baby and new mother are healthy. The real problems start when you get that baby home and realize you have to be a parent. No amount of planning can ever really prepare you for that.

SUMMARY

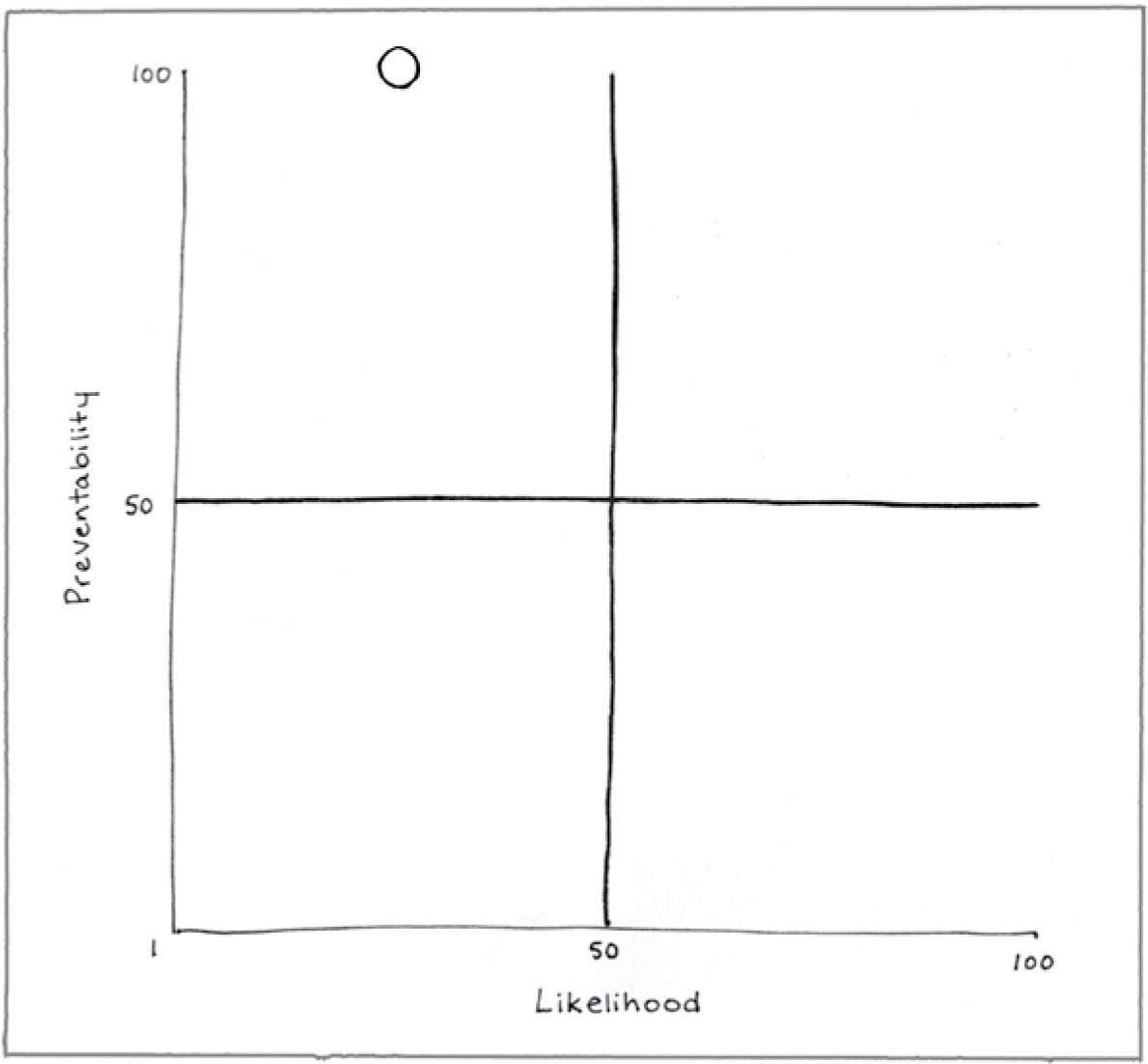

Preventability (100)

In some cases it is much safer to have a baby in the hospital, but ultimately it is up to the mother where she wants to give birth.

Likelihood (28)

The odds of having a C-section or other medical intervention are higher if you give birth in the hospital, but the health outcomes are statistically better for the baby. The rates of infant and maternal mortality are very low for both in-hospital and home births.

Consequence (35)

Having a C-section is good if you really need one, and not so good if you don’t. But while painful and difficult to recover from, it is unlikely to be fatal.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Ten great public health achievements—United States, 1900–1999. MMWR, 48(12), 241–243. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/00056796.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1999). Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Healthier mothers and babies. MMWR, 48(38), 849–858. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4838a2.htm

Central Intelligence Agency. (2017). The world factbook. Retrieved from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2091rank.html

Dominguez-Bello, M. G., De Jesus-Laboy, K. M., Shen, N., Cox, L. M., Amir, A., Gonzalez, A.,. . . Clemente, J. C. (2016). Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean-born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nature Medicine, 22, 250–253.

Snowden, J. M., Tilden, E. L., Snyder, J., Quigley, B., Caughey, A. B., & Cheng, Y. W. (2015). Planned Out-of-Hospital Birth and Birth Outcomes. N Engl J Med 373:2642–2653.