25. FLESH-EATING INFECTION

Hearing the words “flesh-eating infection” might make you head for the hills in fear of a zombie apocalypse, but it is not undead walkers that should cause you anxiety. Rather, this flesh eating is done by bacteria such as group A Streptococcus, Klebsiella, Clostridium, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Aeromonas hydrophila. Flesh-eating infections, also called necrotizing fasciitis, occur when these bacteria enter the body through a break in the skin and multiply. The bacteria damage and destroy connective tissue (fascia) around muscles, nerves, fat, and blood vessels. If the bacteria cannot be contained, the infection can lead to amputations and/or death.

Blisters, cuts, scrapes, scratches, insect bites, and puncture wounds can all provide bacteria with a path into the body. Group A Streptococcus, the same bacteria that cause strep throat, is responsible for most cases of flesh-eating infections. Although many healthy people host group A Streptococcus in or on their bodies, infections usually do not occur. In this case, the immune system likely is able to fend off an attack by the invading bacteria to prevent damage. However, in 500 to 1,500 people in the U.S. each year, the bacteria turn into hungry microscopic beasts that gobble up the skin, muscle, and fat. The bacteria can also release toxic chemicals capable of destroying tissue. Most of the people who develop flesh-eating infections have conditions or illnesses (e.g., cancer, kidney disease, diabetes) that weaken their immune systems, but healthy people can be affected too.

Symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis can come on within just a few hours after an injury. The first signs of an infection usually include pain or soreness that is out of proportion to the visible injury. The skin around the injury may swell, feel warm, and turn red. Other signs of an infection include fever, nausea, weakness, and vomiting. Blisters and spots may also appear, and the area may be tender to the touch. The infection can spread to other parts of the body at a rate up to 1 in (2.5 cm) per hour. To help diagnose an infection and to see the extent of damage, doctors may order a body scan such as a CT scan or an MRI. Untreated, the infection can lead to a drop in blood pressure, sepsis, toxic shock, organ failure, and death.

Unfortunately, the early symptoms of necrotizing fasciitis look similar to the flu or a minor injury. This makes diagnosis difficult. Therefore, a person may not seek immediate medical attention. This can be a fatal mistake because necrotizing fasciitis spreads so quickly. Any delay in treatment reduces a person’s chance of survival. Without treatment, flesh-eating infections are often fatal. Even with treatment, about 25% of the people who contract these infections die.

Treating necrotizing fasciitis usually starts with intravenous antibiotics, often several different types, to fight the offending bacteria. Doctors may also perform surgery to remove damaged tissue and to stop an infection from spreading. In severe cases, an entire arm or leg or other body part must be amputated to save the patient. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBO) has been used to treat necrotizing fasciitis but has not been the subject of rigorous testing for its effectiveness. HBO involves placing patients in a special container where high concentrations of oxygen can be delivered. The high concentration of oxygen slows the growth of anaerobic bacteria to improve healing and preserve healthy tissue.

The best way to prevent an infection is to have good hygiene practices. Open wounds should be washed completely with soap and water. Anyone with an open cut should also stay out of swimming pools, rivers, lakes, and oceans to avoid an infection. The injured site should be kept clean and checked until it is healed. Medical assistance should be sought immediately if the pain from an injury is much greater than expected for the size of the wound. Luckily, necrotizing fasciitis is not usually spread from person to person because bacteria must get into the body through the skin to cause an infection, but it’s a good idea to avoid touching other people’s infected wounds. The odds are good that you wouldn’t want to anyway.

SUMMARY

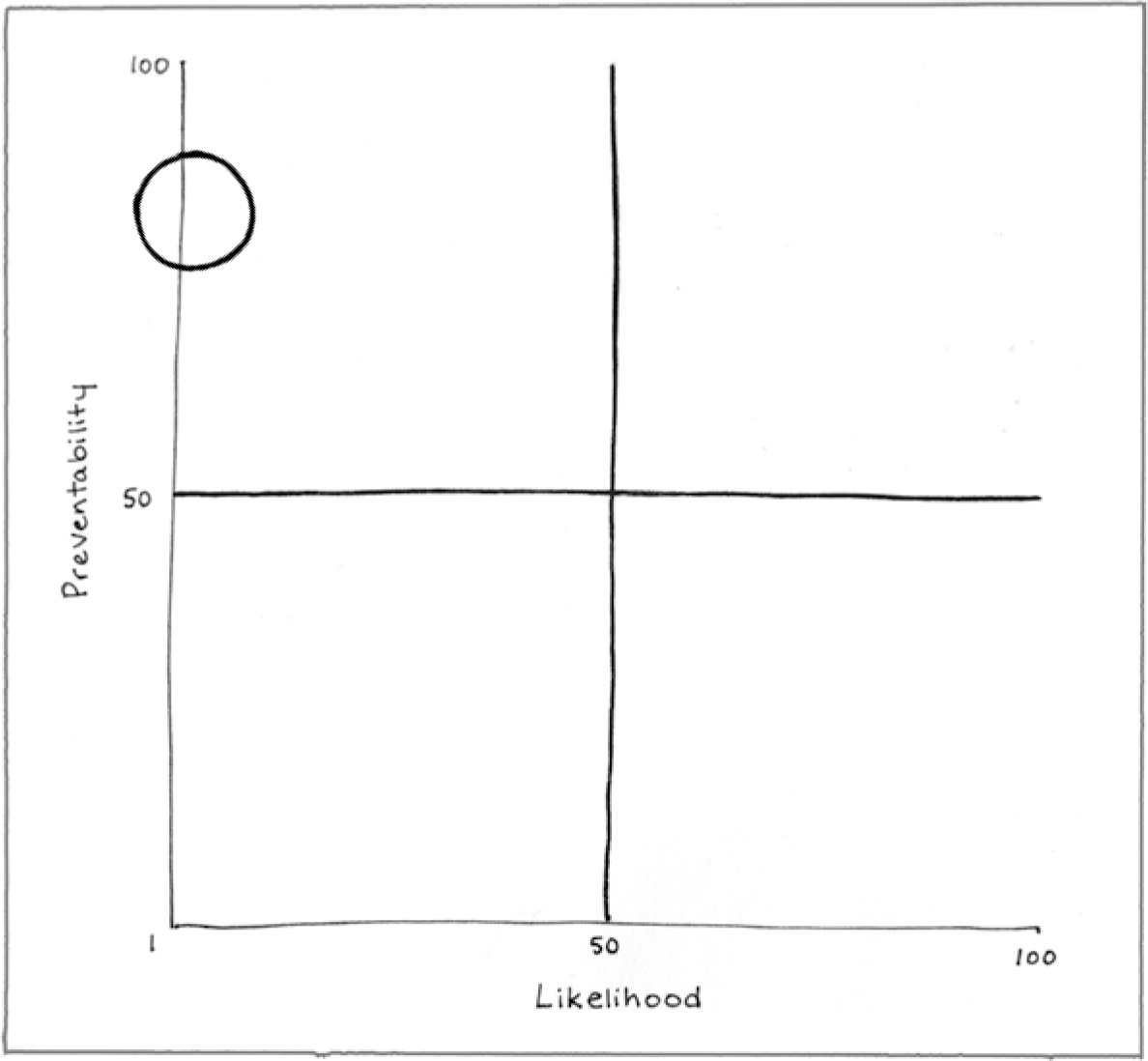

Preventability (82)

Good personal hygiene practices and prompt medical attention will prevent many flesh-eating infections.

Likelihood (4)

The chance of contracting necrotizing fasciitis is low.

Consequence (94)

Without prompt, effective medical treatment, necrotizing fasciitis is often fatal.

REFERENCES

Harbrecht, B. G., & Nash, N. A. (2016). Necrotizing soft tissue infections: A review. Surgical Infections, 17, 503–509.

Tunovic, E., Gawaziuk, J., Bzura, T., Embil, J., Esmail, A., & Logsetty, S. (2012). Necrotizing fasciitis: A six-year experience. Journal of Burn Care Research, 33, 93–100.