28. MOLD

If you are like most people, you don’t have especially warm feelings about mold. We tend to think of these fuzzy microbes as irritants. They spoil our food, give us athlete’s foot, and discolor our shower grout. However, they also give us cheese, soy sauce, and penicillin. And, of course, they play a critical role in the ecosystem, decomposing organic matter and effectively keeping dead plants and animals from piling up everywhere. So, it’s a bit of a mixed bag.

Molds are neither plants nor animals; like mushrooms and yeast, they are fungi. They reproduce by releasing millions of tiny spores that can be dispersed in air or water. Molds are everywhere; you cannot avoid them. There are many, many different kinds of mold, but one thing they all have in common is that they need moisture. This is why molds are notorious for growing in damp places, like basements, bathrooms, and Florida. Molds also need some organic matter to consume, because unlike plants they cannot photosynthesize sunlight. Some molds grow well on oranges, some on wood, and some on the dirt that collects on your windowsills.

Some molds cause infections in humans, typically on the skin. For example, ringworm, nail fungus, and thrush are all caused by mold. More serious infections include valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) and histoplasmosis, which are associated with inhalation of mold spores. People with compromised immune systems are more susceptible to invasive lung infections like aspergillosis, and these types of infections can be difficult to treat. In addition, mold is well known to be allergenic and can exacerbate asthma and other respiratory conditions.

Some molds produce mycotoxins, which, as the name would imply, are poisonous to humans and other animals when they are ingested. These compounds can be neurotoxic, carcinogenic, and teratogenic—all features that you don’t want associated with your food supply. Possibly the most famous mycotoxins are the ergot alkaloids, which are produced by a mold that grows on rye. Consuming contaminated grains causes ergotism, known in the Middle Ages as St. Anthony’s fire. This unpleasant disease is characterized by seizures, abnormal sensations, vomiting, diarrhea, psychosis, and gangrene. In addition to being responsible for a number of historical plagues, ergot poisoning is hypothesized by some to have played a role in the Salem witch trials. In more modern times, ergot alkaloids are used to treat migraine headaches. Some mycotoxins are antibiotics. Some mycotoxins, called trichothecenes, have been developed for chemical warfare. Trichothecenes were discovered to be pathogenic in Russia after an outbreak of serious disease in humans and horses in the 1930s. The culpable fungus was eventually determined to be Stachybotrys chartarum (also known as Stachybotrys atra)—now popularly known as toxic black mold.

Cases of mold-contaminated food still come up from time to time. But if you’re worried about mold, it’s probably because you have heard of toxic mold syndrome (TMS), a controversial and poorly defined condition that is associated with exposure to mold-contaminated environments. Symptoms include headache, eye irritation, stuffy nose and sinuses, bloody nose, fatigue, gastrointestinal problems, and neurological complaints (like difficulty concentrating). Most frighteningly, in the mid-1990s, the CDC identified an association between pulmonary hemorrhage in infants and mold growth in their homes. The report called out Stachybotrys chartarum as a potential causative agent in the cluster of cases they examined in Cleveland, Ohio. This added fuel to the fire of mold-related angst, which would lead to building demolitions, insurance claims, multimillion-dollar lawsuits, and an entire industry specializing in mold removal.

But the connection between environmental mold exposure and human illness is complicated, and TMS remains controversial. A follow-up by the CDC revealed errors in the initial reports on infant pulmonary hemorrhage, and the agency concluded that the connection with mold exposure was unproven. The symptoms of TMS are vague, and the studies that have shown effects have been methodologically flawed. It is not out of the question or even unreasonable to believe that there could be some health effects of living, working, or going to school in a damp building. However, it is difficult to know what to attribute to mycotoxins, mold spores, bacteria (like Legionella, which also lives in damp environments), and chemicals like formaldehyde that may be released from damp building materials. And there is almost certainly a psychological component. There is currently no solid scientific evidence that inhalation exposure to toxic black mold poses a serious threat to human health.

That being said, it is still recommended that you avoid hosting mold in your home. Mold needs water and humidity, so the best thing you can do is keep things dry. Use ventilation fans, air conditioners, and dehumidifiers. Fix water leaks and properly dry any parts of your home that get flooded. Wipe up the condensation on your windowsills. Take care of small patches of mold before they can spread, and, if you have a major mold problem, get a professional to do remediation. Of course, if you get a fungal infection on your skin or in your lungs, you should have it treated. And you shouldn’t eat moldy food. Really, mold is most likely to make you sick if you eat it.

SUMMARY

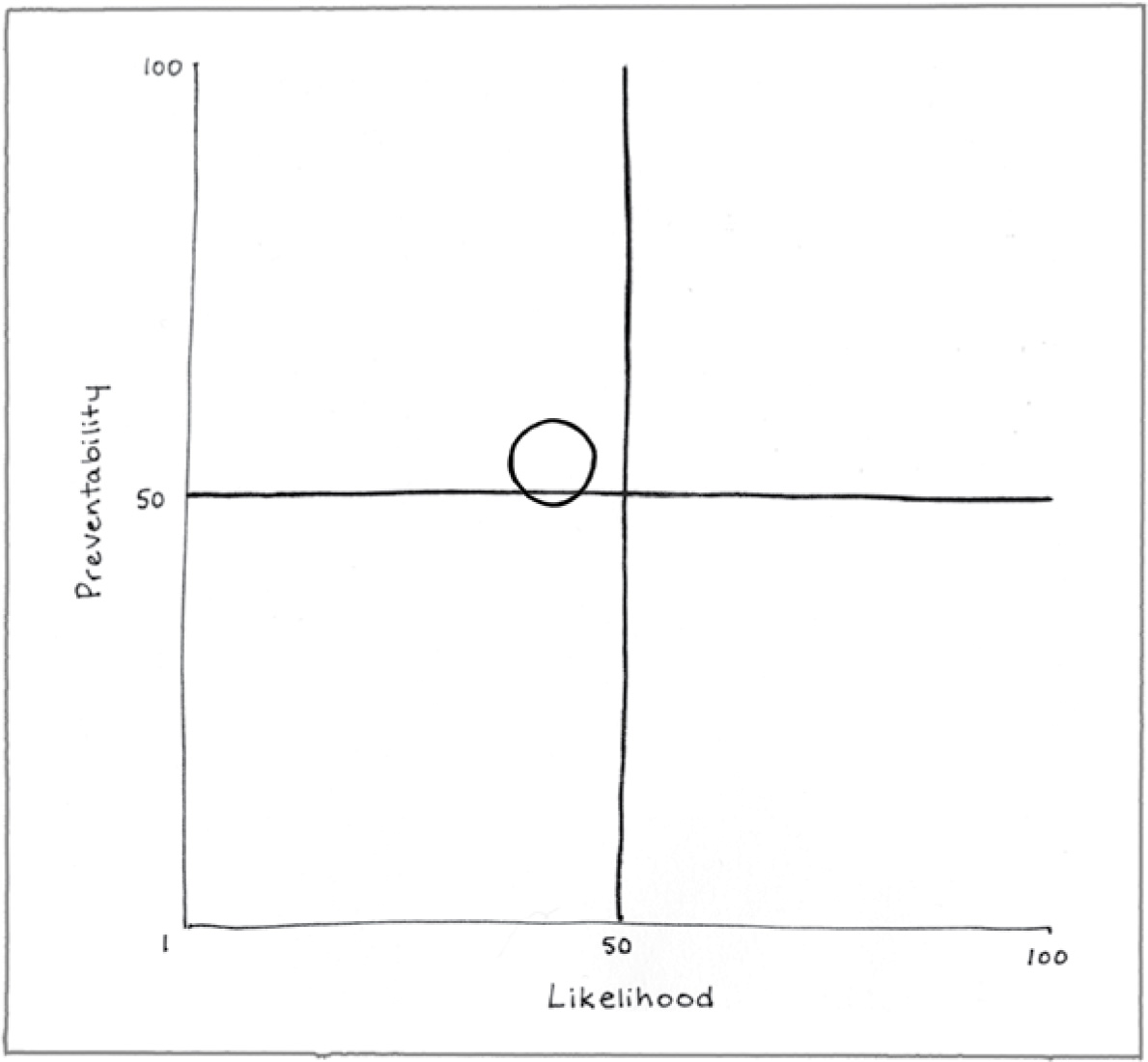

Preventability (53)

You can do your best to reduce mold, but if you live in a damp environment, you should prepare for a long-term war with fungus.

If you eat mold, it will very likely make you sick. If you live in a moldy building, you may have allergies or respiratory problems, especially if are already prone to them.

Consequence (66)

Inhaling mold spores can make you sick, but it probably won’t kill you. Eating toxic mold can make you very sick, but in modern times it is rare for otherwise healthy people to die from mold poisoning.

Bennett, J. W., & Klich, M. (2003). Mycotoxins. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 16, 497–516.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (1997). Update: Pulmonary hemorrhage/hemosiderosis among infants—Cleveland, Ohio, 1993–1996. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 46, 33–35.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2000). Update: Pulmonary hemorrhage/hemosiderosis among infants—Cleveland, Ohio, 1993–1996. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 49, 180–184.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, December 20). Facts about Stachybotrys chartarum and other molds. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mold/stachy.htm

Edmondson, D. A., Nordness, M. E., Zacharisen, M. C., Kurup, V. P., & Fink, J. N. (2005). Allergy and “toxic mold syndrome.” Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology, 94, 234–239.

Fung, F., & Clark, R. F. (2004). Health effects of mycotoxins: A toxicological overview. Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology, 42, 217–234.

Kuhn, D. M., & Ghannoum, M. A. (2003). Indoor mold, toxigenic fungi, and Stachybotrys chartarum: Infectious disease perspective. Clinical Microbiology Review, 16, 144–172.

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2017, September 1). Mold. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/mold/index.cfm

Pettigrew, H. D., Selmi, C. F., Teuber, S. S., & Gershwin, M. E. (2010). Mold and human health: Separating the wheat from the chaff. Clinical Reviews of Allergy and Immunology, 38, 148–155.

Richard, J. L. (2007). Some major mycotoxins and their mycotoxicoses—an overview. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 119, 3–10.