34. FORMALDEHYDE

Formaldehyde is classified as a fixative because it prevents decomposition and putrefaction of tissue, provides structural stability through cross-linking of proteins, and preserves the spatial relationship of biological molecules so that you can study them. That is why it is commonly used by scientists and morticians. If you have ever been in a cadaver lab, the smell of formaldehyde will take you right back. The strong odor of formaldehyde is enough to make some people nauseated. It smells like it must be bad for you. It is. But it’s complicated.

Formaldehyde is an organic (in the chemical sense) molecule; it is the simplest compound in a larger group called the aldehydes. It is a colorless, flammable gas that is soluble in water. When it is dissolved in water, it is called formalin. Formaldehyde occurs naturally and would be present in your bloodstream even if you were never exposed to external sources. This is because it is formed as part of ongoing metabolic processes. Your body doesn’t need formaldehyde, but making it is a necessary intermediate step in the creation of chemicals that your body does need. This is true not just in humans, but also in other animals and plants. A solid block of wood will, in fact, emit a measurable quantity of formaldehyde.

So, a little bit of formaldehyde is clearly okay. But at high enough concentrations, inhalation of formaldehyde fumes irritates the eyes, nose, and throat, and causes respiratory problems and nausea. Skin contact can also cause irritation or allergic reactions. Furthermore, in 2011, the National Toxicology Program classified formaldehyde as a known human carcinogen. Specifically, occupational exposure has been associated with sinonasal cancer (cancer of the nasal cavity and nearby sinuses) as well as leukemia and lymphoma.

This being the case, it makes sense to try to limit your exposure to formaldehyde. And you may be thinking that should be pretty easy to do—just don’t spend a lot of time around preserved tissues, which most of us don’t anyway. But if that’s what you’re thinking, you’re wrong. There is a lot more formaldehyde out there than can be accounted for by the embalming industry.

For one thing, formaldehyde is a by-product of combustion. That includes wood fires, gas stoves, automobile exhaust, and cigarette smoke. But it is also used in building materials, permanent press fabrics, paints, glues, paper products, cosmetics, dishwashing and laundry detergents, fertilizers, and pesticides. The largest share of formaldehyde production is devoted to the manufacture of industrial resins used in composite wood products such as plywood, particle board, and medium-density fiberboard—materials found in most new furniture and cabinetry. Formaldehyde off-gases from these materials over time, which is one of the reasons that concentrations of formaldehyde can be much higher indoors, and much higher in new construction, especially trailers and manufactured homes.

This issue made news after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita when the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) resettled some people displaced by the storms into travel trailers and manufactured homes. After occupying these temporary homes, some residents developed respiratory problems, headaches, and nosebleeds. When the CDC tested the air inside these shelters, they found formaldehyde concentrations up to 0.59 ppm. For reference, average outdoor air usually has a concentration less than 0.1 ppm. Since most of the homes that were tested were more than two years old, it is likely that the initial concentrations of formaldehyde were even higher.

There are some reasons to be concerned about formaldehyde exposure, but there are also some things you can do to reduce your exposure. Formaldehyde is easy to smell, even in small concentrations. So, if your home, office, or furniture smells noxious, it’s a good bet that it is off-gassing formaldehyde. One of the easiest things to do is open a window or turn on a ventilation fan. If you have the option to let your furniture air out in a garage for a while, by all means, let it air out until it doesn’t smell. Be picky about the furniture and cabinets you buy. Ask what they are made of and whether they contain formaldehyde. Wash permanent press fabrics before you wear them or hang them up as curtains. Don’t smoke cigarettes, or, at the very least, don’t smoke inside your home. Keep your home as cool and dry as possible because heat and humidity increase off-gassing. Read labels and be conscious of what preservatives are in the cosmetics and cleaners you buy. Formaldehyde can masquerade under different names and can be listed in product ingredients as formalin, formic aldehyde, methanediol, methanal, methyl aldehyde, methylene glycol, and methylene oxide. You can check the Household Products Database (maintained by the Department of Health and Human Services) for specific products containing formaldehyde. In addition, be on the lookout for these eight formaldehyde-releasing preservatives: benzylhemiformal, 5-bromo-5-nitro-1,3-dioxane, 2-bromo-2-nitropropane-1,3-diol, diazolidinyl urea, 1,3-dimethylol-5,5-dimethylhydantoin, imidazolidinyl urea, quaternium-15, and sodium hydroxymethylglycinate. Until 2014, Johnson and Johnson’s iconic baby shampoo contained quaternium-15, and these preservatives can still show up in some familiar products.

If you have an old house, an old couch, and an old kitchen, pat yourself on the back. The formaldehyde is probably long gone. Of course, if your house is really old, you’ll still need to watch out for lead paint.

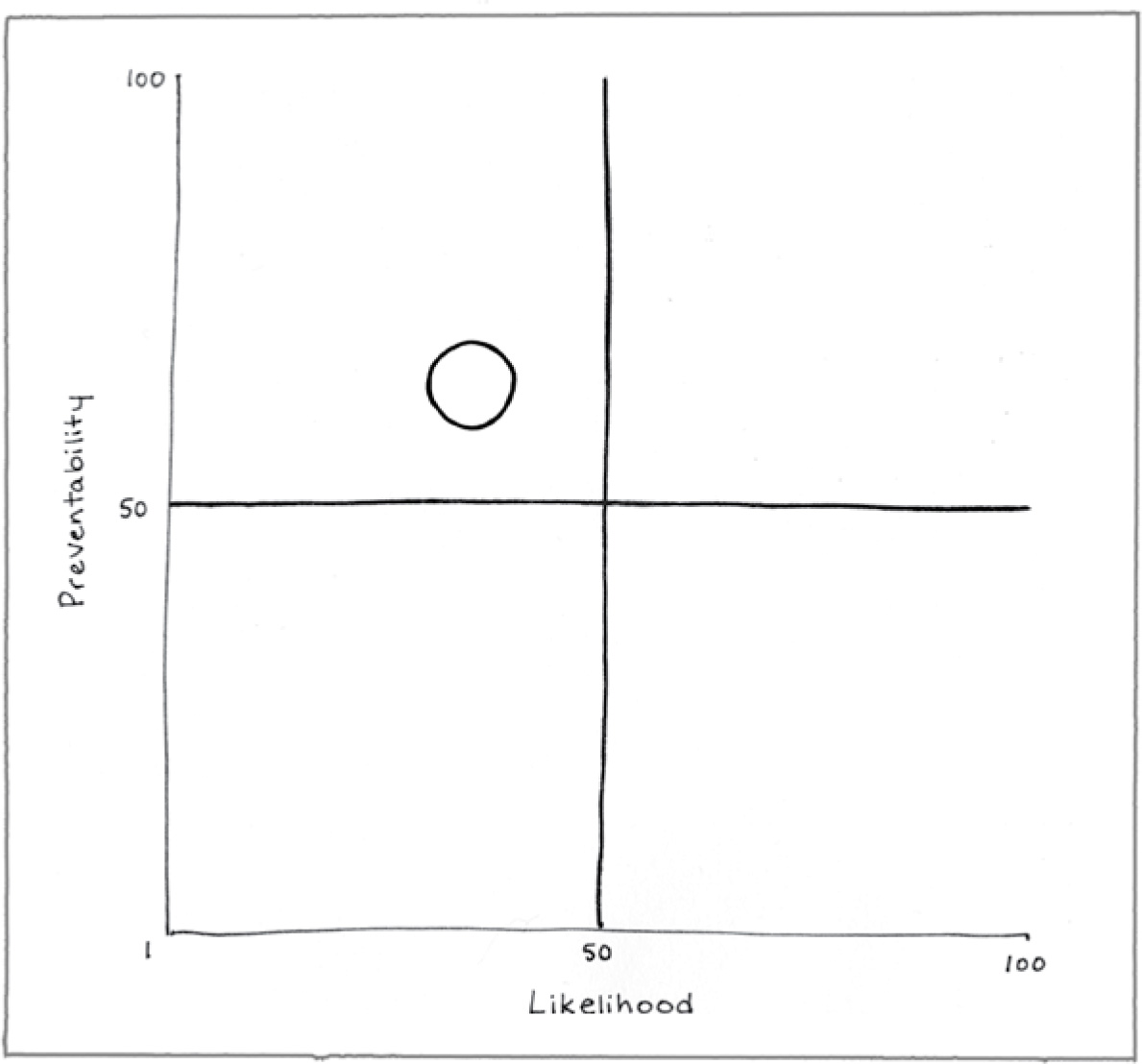

Preventability (65)

With some effort, you can reduce your exposure to formaldehyde at home. But if you work or go to school in a nice new building, you might still be exposed to it.

Likelihood (35)

Unless you are more sensitive than most, small exposures to formaldehyde are unlikely to cause problems. But if you have asthma or other respiratory problems, or if you get a whopping dose, you could get sick.

Long-term exposure to high levels of formaldehyde is linked to respiratory issues and cancer.

REFERENCES

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. (2016, February 10). Formaldehyde in your home: What you need to know. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/formaldehyde/home/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). What you should know about formaldehyde. Retrieved February 26, 2018, from https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/drywall/docs/whatyoushouldknowaboutformaldehyde.pdf

National Cancer Institute. (2011, June 10). Formaldehyde and cancer risk. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/substances/formaldehyde/formaldehyde-fact-sheet

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2017, August 28). Formaldehyde. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/formaldehyde/index.cfm

National Toxicology Program, Department of Health and Human Services. (2016). Formaldehyde. Retrieved from https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/roc/content/profiles/formaldehyde.pdf

Thavarajah, R., Mudimbaimannar, V. K., Elizabeth, J., Rao, U. K., & Ranganathan, K. (2012). Chemical and physical basics of routine formaldehyde fixation. Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, 16, 400–405.

United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2017, June 15). Facts about formaldehyde. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/formaldehyde/facts-about-formaldehyde