36. MERCURY

Mercury is the 80th element in the periodic table and is abbreviated Hg, from a Greek word meaning “water-silver.” It is also commonly known as quicksilver because, although it is a metal, it has the unique property of being a liquid at room temperature (and standard atmospheric pressure). It has been used by humans since ancient times, and pretty much everyone in history has been able to agree that it is super cool. Mercury has long been used for both magical and medicinal purposes. It was once a popular, if ultimately unsuccessful, treatment for syphilis. It also has some legitimately useful properties. For instance, it can dissolve gold and silver in amalgams, which is helpful in both mining and dentistry. It has been used in thermometers and fluorescent lamps and dental fillings and antiseptic ointments and skin-lightening creams and fishing lures and (famously) hat making. Really, it is tremendously useful. Unfortunately, it is also incredibly toxic, which is why the Mad Hatter was mad (crazy, not angry).

Mercury exists in a variety of forms. Elemental, or pure, mercury is the silvery liquid that we think of when we think of mercury. Divalent mercury tends to exist as a compound or mercury salt. Organic mercury has carbon attached, often as a methyl group (carbon and three hydrogen atoms). But no matter what form it comes in, mercury is bad for your health.

The most dangerous thing about elemental mercury is the vapors, or fumes. This might sound strange, because we don’t think of metals as being particularly vaporous. But we’ve already established that mercury is weird stuff, and part of its weirdness is extreme volatility, or tendency to evaporate. Inhaling high concentrations of mercury vapor causes acute lung damage, pneumonia, and possibly death. Even at lower concentrations, inhaled mercury is easily absorbed into the blood, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and causes permanent brain damage. Over time, the body converts elemental mercury into divalent mercury, which accumulates in the kidneys, where it causes additional damage. As is generally the case, children and fetuses are more susceptible to mercury toxicity.

The extreme toxicity of mercury wasn’t generally known until the middle of the 20th century. But now that we know how nasty it is, we tend not to use it. Thermometers are now commonly made with alcohol, and it is illegal to sell mercury-filled fishing lures. Unfortunately, there is still a lot of legacy mercury floating around. People keep old thermometers or they have jars of mercury in their garages. Most unfortunately, a lot of mercury still exists in schools, both in thermometers and just sitting around in supply closets. Historically, many schoolchildren were given blobs of mercury to hold in their hands and play with. It made science fun (but toxic). Although this practice has been discontinued, the mercury might still be around, waiting to be spilled or misappropriated by curious children. This is bad, because mercury is difficult (and expensive) to clean up. Just sweeping it up or washing it down the drain isn’t good enough. It lingers, it spreads, and it causes brain damage. A Scientific American article ominously titled “Dangerous Mercury Spills Still Trouble Schoolchildren” (Knoblauch, 2009) reports that a mercury thermometer broken in a home bathroom caused significant levels of mercury vapor twenty years after it was broken. So, while we can all agree that it looks cool, elemental mercury is not something to mess around with. This is something that should be communicated to all children.

Elemental mercury is still used in gold mining around the world, and poses a major threat to the miners and their communities. But it is rarely used for this purpose in the United States. The other common First World exposure to elemental mercury is through dental amalgams, which contain about 50% elemental mercury. Given the previous paragraph, this might sound scary. However, these fillings have been used for about a hundred years, and extensive research from around the world has failed to show any association between amalgam fillings and health problems, except in a small number of hypersensitive people. If it still makes you nervous, there are other types of fillings you can get. But the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not recommend removing any amalgam fillings you already have. This would, among other things, expose you to more mercury vapor.

Most of the talk of mercury these days has to do with fish. That’s because fish are a known source of an organic form of mercury, methylmercury. Awareness of methylmercury as a public health issue followed a mass poisoning event in Minamata, Japan, in 1956. A chemical company dumped industrial wastewater containing high concentrations of methylmercury into Minamata Bay, where it accumulated in fish and shellfish—dietary staples for the local population. Unlike other forms of mercury, methylmercury is easily absorbed by the digestive tract and doesn’t clear from the body quickly. It accumulates in humans, just as it does in fish. As a result, thousands of people acquired what would later be called Minamata disease, a syndrome characterized by a constellation of neurological symptoms, leading to death in severe cases.

Obviously, very high concentrations of methylmercury are toxic and, thankfully, Minamata is a special case in this regard. But there is a fair bit of mercury kicking around in both fresh and saltwater sources around the world. This is partly due to human causes, like industrial pollution and coal-burning emissions, and also partly due to natural sources, like erosion of mercury ore. All of this means that virtually all fish and shellfish will contain some mercury, and this is concerning, especially when it comes to children and pregnant women. On the other hand, fish is really good for you, especially during neurocognitive development. Scientists and public health authorities have struggled to balance these two truths.

Part of the problem is that the data about the health effects of mercury in fish are incomplete and often contradictory. There are several reasons why this might be true. First, the effects may be small. In addition, fish with high concentrations of methylmercury may also have high concentrations of other contaminants like PCBs, arsenic, and lead. There are also other dietary and environmental sources of mercury that may be difficult to control. There may be some nutritional components of fish that counterbalance or even outweigh the effects of mercury, or some people may consume other foods that have a protective effect. Finally, genetic and epigenetic factors mean that people react differently to similar quantities of mercury, making it difficult to generalize results. Ongoing research is directed at untangling some of these issues.

Taking all of this into account, the FDA recommends that pregnant women and children eat fish, but not too much. It also matters what kind of fish you eat. Because methylmercury accumulates, fish higher up in the food chain will have more mercury than fish closer to the bottom. So, no shark. At the same time, it’s better to eat fish with higher omega-3 fatty acid content, like salmon or sardines.

In the good news column, an international treaty called the Minamata Convention was adopted in 2013 that should decrease the global level of mercury pollution. The bad news is that mercury is not going to stop being a problem any time soon.

SUMMARY

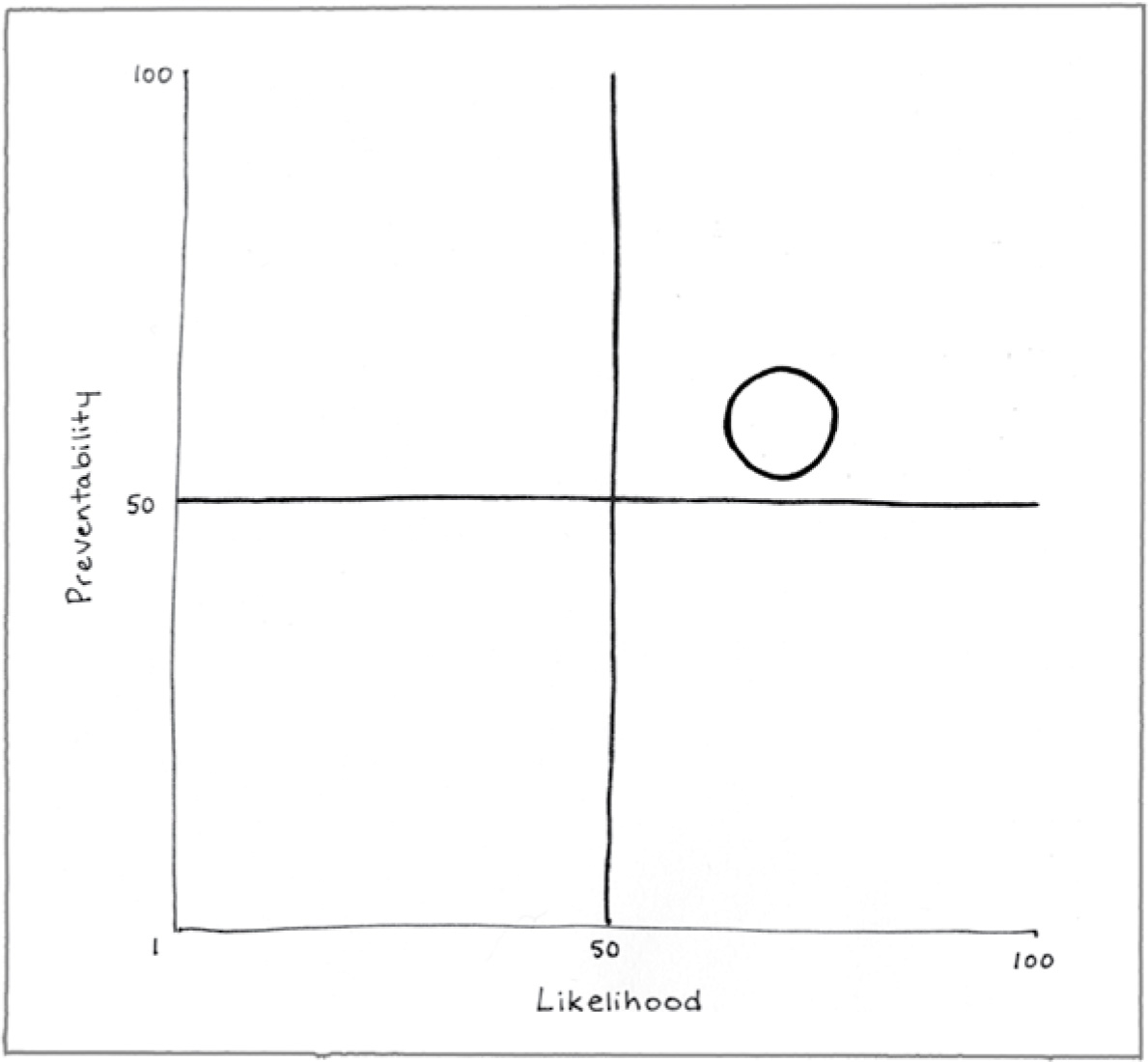

Preventability (58)

You can reduce your exposure to methylmercury by choosing seafood wisely. But fish is still considered a health food, and all fish will have some methylmercury. You can reduce your exposure to elemental mercury by staying away from it and by teaching your children to do the same. But it’s hard to know if someone broke a mercury thermometer in your apartment two decades ago.

Likelihood (68)

Exposure to elemental mercury is quite likely to produce negative health outcomes. It is more difficult to know how moderate exposure to methylmercury might impact health, and the answer could be “it depends.”

Consequence (89)

They called them “mad hatters” for a reason.

Ekino, S., Susa, M., Ninomiya, T., Imamura, K., & Kitamura, T. (2007). Minamata disease revisited: An update on the acute and chronic manifestations of methyl mercury poisoning. Journal of Neurological Science, 262, 131–144.

Ha, E., Basu, N., Bose-O’Reilly, S., Dórea, J. G., McSorley, E., Sakamoto, M., & Chan, H. M. (2017). Current progress on understanding the impact of mercury on human health. Environmental Research, 152, 419–433.

Knoblauch, J. (2009, May 5). Dangerous mercury spills still trouble schoolchildren. Scientific American, Environmental Health News. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mercury-spills-trouble-schoolchildren/.

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. (2017, September 28). Mercury. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/health/topics/agents/mercury/index.cfm

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2017, December 5). About dental amalgam fillings. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/DentalProducts/DentalAmalgam/ucm171094.htm

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2004, March). What you need to know about mercury in fish and shellfish. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/food/foodborneillnesscontaminants/metals/ucm351781.htm

World Health Organization. (2017, March). Mercury and health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs361/en/