47. MOSQUITOES

Mosquitoes have been called the most dangerous animal on Earth. This is obviously not because of their huge teeth, but because of the deadly diseases they spread. These insects are capable of spreading a host of human diseases, including malaria, dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya, Zika, Japanese encephalitis, and West Nile virus. Billions of people are at risk from mosquito-borne diseases: 2.5 billion people (40% of the world’s population) are at risk for contracting dengue alone. Dengue virus infects approximately 400 million people each year.

Male mosquitoes eat flower nectar, but female mosquitoes feed on the blood of other animals to produce eggs. Mosquito bites can be itchy and unpleasant, but the bite itself is rarely dangerous. The problem is that mosquitoes usually bite more than one animal, and in so doing they can acquire and then distribute human diseases. When mosquitoes infected with viruses or parasites bite, they inject a small amount of saliva containing the infectious agent into their blood meal host. When Anopheles mosquitoes infected with Plasmodium protozoan parasites (P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. malariae, P. ovale) bite, the result is malaria. The parasites release toxic substances into a person’s bloodstream that kill red blood cells and result in symptoms including fever, nausea, chills, headache, and general malaise. The parasites can invade and damage the brain, liver, kidney, and lungs. Many people who have contracted malaria do not show symptoms of the disease for several weeks after they are bitten by an infected mosquito. Malaria can be cured if it is diagnosed and treated quickly. However, malaria that affects the brain is especially dangerous and lethal. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that worldwide there were 212 million cases of malaria and 429,000 people died of malaria in 2015.

Yellow fever, dengue, Zika virus, and chikungunya are viral diseases spread by Aedes mosquitos. The virus that causes Japanese encephalitis and the West Nile virus are spread primarily by Culex mosquitoes. These diseases share some symptoms such as fever, headache, and joint and muscle pain. In addition to this shared set of symptoms, each of the different viruses throws in its own particular unpleasantness. For example, people with yellow fever may experience low blood pressure, skin rashes, and liver and kidney failure that can be fatal. Untreated, dengue can affect the central nervous system, circulatory system, and respiratory system and cause depression, seizures, breathing problems, and shock. With prompt and proper management, death from these infections is not common. However, symptoms and suffering can persist for years after the initial sickness.

People who live or travel in tropical areas of Asia, Africa, South America, Central America, and the Pacific are at the highest risk of yellow fever, dengue, chikungunya, and Japanese encephalitis. But North America is not safe from these viruses: West Nile virus and Zika virus have both been found in the United States. West Nile virus is spread when mosquitoes feed on infected birds, such as crows, or other animals; the virus is then transmitted to people through the bite of infected mosquitoes. Although the majority of people who are infected with West Nile virus remain free of symptoms, other people may experience flu-like symptoms, fatigue, sensitivity to light, and rashes several days after becoming infected. A small proportion (1 in 150) of people infected with West Nile virus will develop encephalitis, meningitis, or paralysis, and about 1 in 10 of these people will die. Likewise, many people infected by the Zika virus remain symptom free or suffer only mild symptoms. Recently, Zika virus has been linked to the development of Guillain-Barré syndrome, a neurological disorder that damages nerves and muscles and can cause paralysis. As most people have heard by now, women infected with Zika virus while they are pregnant are at risk of giving birth to babies with serious brain defects, including microcephaly.

Governmental agencies and commercial companies around the world have taken many steps to protect the public from mosquito-borne illnesses. Effective mosquito control takes into account mosquito physiology and biology, life cycle, feeding habits, and mechanisms by which viruses spread. Professionals and the general public can help prevent the spread of mosquito-borne diseases by eliminating the breeding grounds (e.g., standing water) where mosquitoes lay eggs and hatch. Insecticides to kill larval and adult mosquitoes and reduce the risk of disease may also be used. Research using genetic modification methods shows some promise for controlling mosquito populations, but it is controversial.

The best efforts by professionals to prevent mosquito-borne diseases are often not enough. Individuals can take some responsibility for their own health and protect themselves if they live in or travel to areas with a high prevalence of mosquito-borne diseases. For example, people can be vaccinated against yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis. However, there are no vaccines for other diseases such as Zika and malaria. Unfortunately, the ingredients (e.g., preservatives, animal proteins) in some vaccines cause allergic reactions in some people. Prophylactic drugs to protect against malaria are available, but their effectiveness is variable, and they may interact poorly with other drugs or medications.

Everyone who will be in an area that has a high incidence of disease spread by mosquitoes should take protective measures. These steps start with knowing what diseases pose a potential risk and when mosquitoes are most likely to bite: some mosquitoes bite primarily during the day, while others are most active at dawn, dusk, or evening. Insect repellents applied to the skin can significantly reduce the chance of a mosquito bite (see chapter about DEET). People can reduce the risk of contracting a disease by applying insect repellents to long-sleeved shirts, long pants, and hats that they wear and by sleeping under mosquito nets.

For many people, mosquitoes and their bites are not just a simple annoyance; instead they pose a serious health threat.

SUMMARY

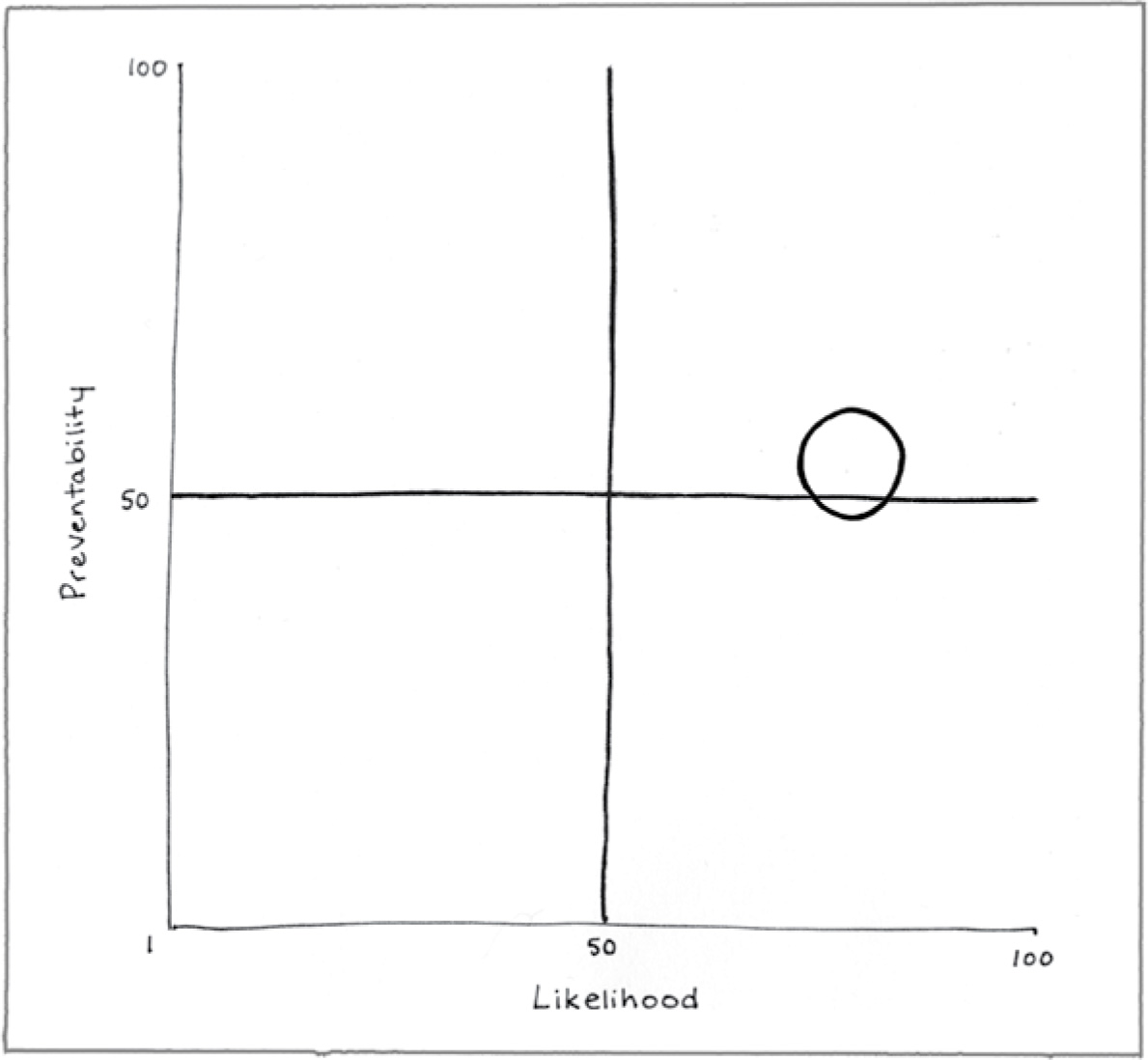

Preventability (53)

Insecticides and insect repellents can reduce the risk of mosquito-borne illnesses, but mosquito management has proved to be difficult in many parts of the world.

Likelihood (82)

The high incidence of mosquito-borne disease is a global health threat.

Consequence (88)

A mosquito bite may cause minor, local skin irritation, or it can transmit life-threatening disease.

REFERENCES

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, August 2). West Nile virus. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/westnile/symptoms/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 10). Malaria. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/malaria/

World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia. (n.d.). Dengue. Retrieved from http://www.searo.who.int/entity/vector_borne_tropical_diseases/data/data_factsheet/en/