51. PUBLIC SWIMMING POOLS

Not all of us can afford to have a private swimming pool. Instead, we turn to public pools to cool off and exercise. Nothing is more refreshing than a dip in a pool on a hot summer day, unless it is accompanied by mouthful of water polluted with fecal matter and other human grime. Unfortunately, this may be the case more often than we would like to believe. Some public pools might be compared to cesspools because of the contaminated water people swim in. Sweat, urine, fecal matter, oil, and dirt can all end up in the pool water when we take a swim.

Several potential contaminants lurk in the blue waters of public pools. In 2012, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tested the water from public pool filters in the metro Atlanta area. Of the 161 water samples tested by the CDC, 93 (58%) tested positive for Escherichia coli bacteria. The presence of E. coli in the water indicated that swimmers deposited fecal matter in the water. Ingestion of E. coli can cause severe gastrointestinal problems and other health issues. In addition to finding E. coli in the water samples, the CDC researchers detected Pseudomonas aeruginosa in 95 (59%) of the samples, Giardia intestinalis in two (1%) of the samples, and Cryptosporidium species in one (0.6%) of the samples, all microbes that can cause human illness such as skin problems, conjunctivitis, diarrhea, nausea, fever, and respiratory problems. Cryptosporidium parasitic infectious outbreaks linked to swimming pools increased from 16 outbreaks in 2014 to 34 outbreaks in 2016.

People expect pool owners and operators to keep their facilities clean, but this is often not the case. The CDC found that 78.5% of water areas reported health violations, and 12.3% of these violations were serious enough to cause an immediate closure of the facility. To help reduce the risk of illness and injury at public pools, the CDC issued the Model Aquatic Health Code (MAHC), which describes best practices for pool design, maintenance, operation, and inspection. However, the MAHC guidelines are voluntary, and it is up to local municipalities to regulate and inspect public pools. For whatever reasons, such as insufficient funds, lack of trained staff, or outright negligence, public pools may not be as clean or as safe as they should be.

The blame for poor pool water quality does not fall only on the owners and operators of pools. Swimmers must take some responsibility for keeping their public pools clean. A 2012 survey commissioned by the Water Quality and Health Council revealed that 43% of swimmers do not shower before they enter a pool. Because showering can reduce the number of microbes on a person’s body, skipping a shower dumps potentially dangerous bacteria into the pool water where other people can ingest it while they swim. The survey also found that 19% of the respondents admitted to urinating in the pool; 11% of the respondents said they swam with a runny nose; 8% of the respondents said they swam with an exposed rash or cut; and 1% said they failed to report when children soiled their diaper or bathing suit while in the pool. All of these behaviors can contaminate the water with microbes that can sicken people.

Disinfection of pool water with chemicals such as chlorine is the primary way to reduce the transmission of infection. In appropriate concentrations, these chemicals kill dangerous bacteria and viruses in pool water. Maintenance of proper water pH levels with acids, such as hydrochloric acid, ensures that chlorine remains effective in killing pathogens. When used or stored improperly, these chemicals can cause burns or respiratory problems. Even when used as recommended, pool disinfectants form other chemicals (disinfection by-products) when they interact with urine, sweat, and skin cells in the water. Chlorine, for example, produces chloramines that produce the noxious smell in indoor pools and irritate eyes. Some of these chemical by-products are mutagenic or carcinogenic, and chronic exposure to these chemicals may increase the risks of developing bladder cancer, asthma, and other respiratory illnesses.

Swimming is one of the best forms of exercise for people of all ages. It’s a full-body workout without the wear and tear of other exercises such as running. But if you swim in a pool, some simple steps will help protect you and others from picking up an unwanted infection. Start with good hygiene before you dive into the pool. Take a shower to wash off bacteria before it gets into the water. If you are swimming with children, make sure they shower, especially if they have used the toilet or had their diapers changed. Children should take bathroom breaks from the pool so they aren’t tempted to use the pool as their toilet. Adults should also use the bathroom and refrain from using the pool as a communal toilet. Infants in the pool should have their diapers checked often to make sure they aren’t soiled. Diapers are not effective in keeping pathogens out of the pool. If you have diarrhea, do not go into the pool. Most importantly, do not swallow pool water. Keep your mouth closed—you never know what someone else has left behind in the pool.

SUMMARY

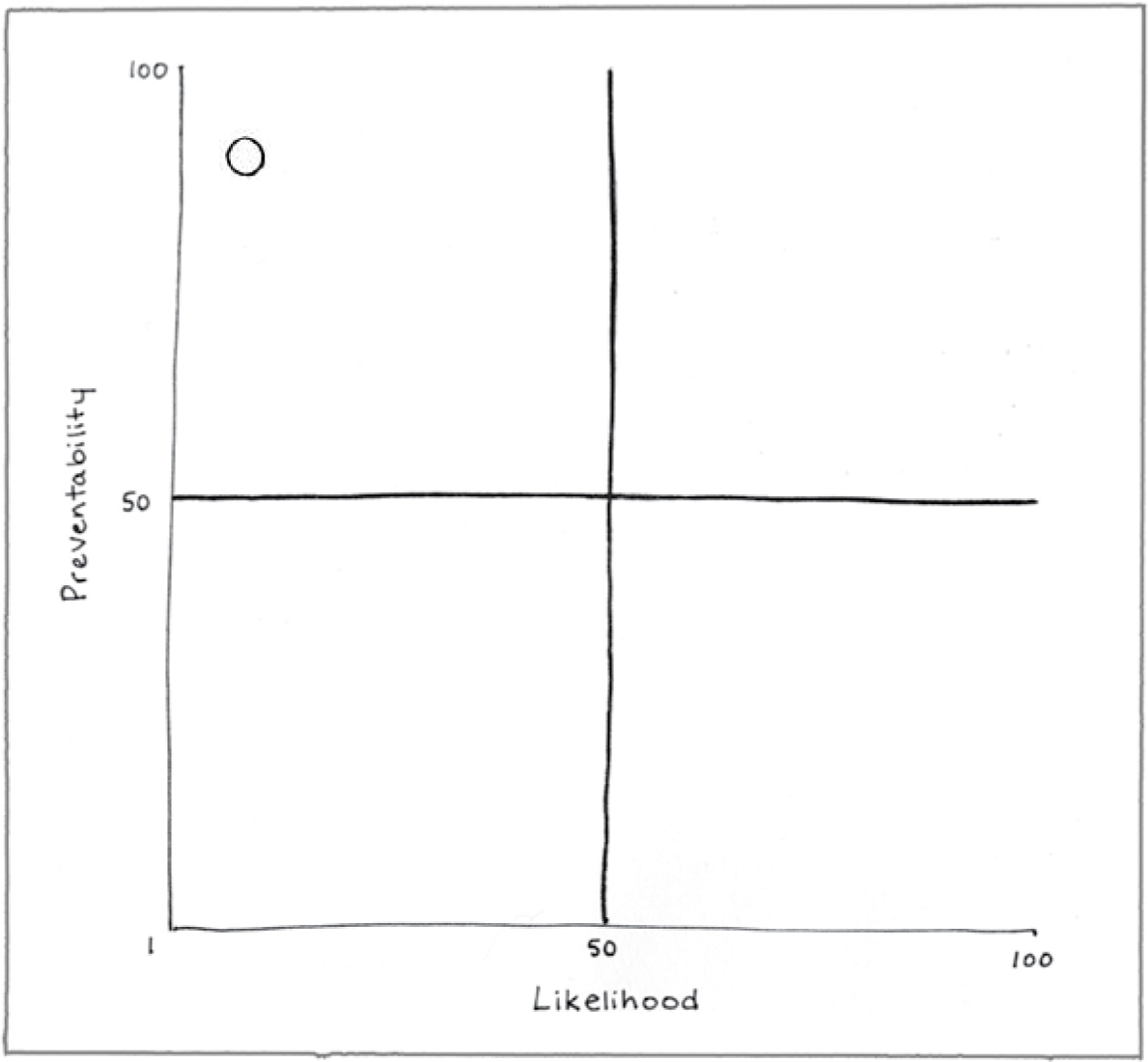

Preventability (89)

Proper pool maintenance and good hygiene practices will prevent many of the health risks associated with public pools.

Although pools may be contaminated, the likelihood of becoming ill after swimming in a public pool is low.

Consequence (27)

The symptoms associated with most infections that people contract after using a public pool are mild to moderate and temporary.

Amburgey, J. E., & Anderson, J. B. (2011). Disposable swim diaper retention of Cryptosporidium-sized particles on human subjects in a recreational water setting. Journal of Water and Health, 9, 653–658.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2009). Pool chemical-associated health events in public and residential settings—United States, 1983–2007. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 58(18), 489–493. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5818a1.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Immediate closures and violations identified during routine inspections of public aquatic facilities—network for aquatic facility inspection surveillance, five states. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 65(5), 1–26.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2013). Microbes in pool filter backwash as evidence of the need for improved swimmer hygiene—Metro-Atlanta, Georgia, 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 62(19), 385–388. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6219a3.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Model Aquatic Health Code. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/mahc/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, May 18). Crypto outbreaks linked to swimming have doubled since 2014. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p0518-cryptosporidium-outbreaks.html

Richardson, S. D., DeMarini, D. M., Kogevinas, M., Fernandez, P., Marco, E., Lourencetti, C., . . . Villanueva, C. M. (2010). What’s in the pool? A comprehensive identification of disinfection by-products and assessment of mutagenicity of chlorinated and brominated swimming pool water. Environmental Health Perspectives, 118, 1523–1530.

Wiant, C. (2012). New public survey reveals swimmer hygiene attitudes and practices. International Journal of Aquatic Research and Education, 6, 201–202.