7. ORGANIC PRODUCE

Organic produce is pricey, and sometimes very pricey. But increasingly, we are buying it. Not surprisingly, we are doing this because we think it is better. Surveys show that when we pay a premium for organically grown produce, we think we are making a choice that is healthier for ourselves and for the environment. This message is heavily reinforced by celebrities, peer pressure, internet consensus, and, of course, advertising. Critics, however, confidently assure us that this is propaganda, and that only suckers pay the extra cost. Nobody wants to be a sucker, but nobody wants to feed their child a pesticide cocktail disguised as an apple either. Unfortunately, a dig into the literature on this topic turns up a contradictory mess.

The idea of organic farming emerged in the early 20th century when some people noticed that the use of synthetic fertilizers was depleting the microbial community of the soil (which is bad). This led to the concept of holistic farming: considering all the parts of the farm as an organism rather than focusing exclusively on crop production. This is where the confusing and unfortunate name “organic” comes from. For those wondering, it is not derived from or related to the chemical definition of “organic” (carbon based). Moreover, the opposite of organic is conventional. There is no such thing as an inorganic carrot. In any case, one of the driving forces behind the organic movement was the idea that natural is better. Over time, nostalgia and anticorporate sentiment have worked their way into the mix.

Consumers started to get on board with this idea, but for a long time it was up to farmers to decide what counted as organic. In 1990, Congress created the National Organic Program, which rolled out standards for organically grown crops in 2000. At present, “organic” is defined as a set of agricultural practices regulated by the government. Any product carrying the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) organic mark should meet the standards outlined by that agency. According to the USDA’s website, “organic operations must demonstrate that they are protecting natural resources, conserving biodiversity, and using only approved substances.”

That sounds good. But wait, detractors say, not so fast. What are those “approved substances”? Well, the USDA tells us, “the use of most synthetic pesticides and fertilizers” is prohibited. So, here is an important point: contrary to popular belief, the organic mark does not mean that no fertilizers and pesticides have been used. It means that most synthetic fertilizers and pesticides have not been used. One of the top reasons consumers give for choosing organic is that they want to reduce their exposure to pesticides, and that is a reasonable goal. Synthetic pesticides have a bad reputation, for good reason. However, their natural counterparts are not necessarily better for you, and in some cases they may be worse. You might love nature, but that doesn’t mean that nature loves you. Plants can produce toxins that are inadvisable to eat (hemlock, anyone?). Likewise, it may be inadvisable to distill these toxins down to powder and dust your food crops with them. Rotenone, a pesticide and piscicide (fish killer) naturally found in jicama, among other species, is the example people like to give. Rotenone is naturally derived, but it’s also a fairly toxic chemical that has been associated with Parkinson’s disease. Notably, it is approved for use in organic farming. Furthermore, the use of synthetic pesticides in the United States is very tightly regulated. The concentrations of these compounds found in the American food supply are far below the levels that would pose a health risk.

And is organic farming really better for the environment? Some say no. One of the biggest issues is crop yield: you can’t grow as much food using organic practices. This means you need to devote more land to agriculture—which could lead to deforestation. Not to mention that if all farms used manure as fertilizer, we would need a lot more manure. If we don’t have the land for crops, we definitely don’t have the land to raise animals, and methane is a greenhouse gas. Many critics say that if everyone converted to organic methods, we wouldn’t be able to feed the world’s population. Most people will agree that widespread famine is a bad thing.

These critiques are valid, and they bring up some important points that are worth acknowledging. First, we should not conflate “natural” and “healthy.” Many times these two categories overlap, but they are not synonymous. Furthermore, using a natural product in a highly unnatural way isn’t really natural. For this reason, the organic guidelines may be misguided. Second, the local good and the global good are not always compatible. Organic practices may be best for the ecosystem of any individual farm, but that doesn’t mean it will be best for the environment as a whole. Likewise, what is best for an individual consumer is not always best for everyone in the world. If a few people in affluent countries enjoy better health while many people in poorer countries go hungry, it’s difficult to call that a positive outcome.

Nevertheless, critics of the organic movement are also painting an incomplete picture. A review by Seufert and Ramankutty (2017) summarizes the potential benefits and costs of organic agriculture. It is a well-balanced review, and worth reading. The authors outline the following points. Organic farming produces lower yields than conventional farming, but the difference is variable: it depends on the crop and on specific management techniques. For some crops, organic management makes more sense than for others. It is clearly better from a biodiversity perspective, but there may be a trade-off between this benefit and crop yields. Organic management does seem to have a positive impact on soil quality. Greenhouse gas emissions are lower per unit area, but higher per unit of production, but again, the magnitude of this effect depends on the crop. A great deal of uncertainty remains about the relative impact of organic farming on water quality as well as the overall quantity of water used. Farmworkers and people who live on and around organic farms are exposed to fewer pesticides, and the higher price of organic produce turns a higher profit for farmers, many of whom live in low-income countries. Unfortunately, that (much) higher price is paid by consumers. In some cases consumers are paying 50% more for organic produce than they would for the conventionally grown equivalent—far more than the 7–8% premium that would be required to compensate for the reduced yield. Consumers who can afford the price are enjoying food with demonstrably reduced pesticide residues and arguably (if marginally) better nutrient profiles. However, at least in high-income countries where pesticide residues are already far below safe thresholds, it’s unclear whether this adds up to any real health benefit. The feasibility of scaling up organic agriculture is unclear. The nitrogen (fertilizer) issue is a problem, although the magnitude of the problem is under debate. The overall message is: organic farming has some advantages and some disadvantages, and the balance depends on context. Also, more data are still needed. In any case, it doesn’t appear that organic farming is the magic bullet to solve all of our food-related problems.

The USDA organic regulations are not intended to provide safer or healthier options to consumers. Instead, these regulations are designed to provide options that are more natural and have a lower impact on the local environment. No matter what anyone says, there is a good argument for natural practices: they have gone through extensive empirical testing. That does not mean, however, that what worked in the past is going to continue to work forever. If, as a society, we don’t want to use pesticides, we might need to think about genetically modified organisms. If we don’t want chemical fertilizers, we might need to accept the use of sewage sludge. Both of these practices are prohibited by organic regulations. If you find these things anathema because they are unnatural, remember, there isn’t anything particularly natural about farming to begin with. Humans are the only species on earth that engage in agriculture, and we have only been doing it for about 15,000 years. To have a farm at all is a novelty. If you would like to eat organic but can’t afford it, you should still eat conventionally grown produce, and you should eat a lot of it. You should believe that it is safe, because studies show that it is. Whatever kind of produce you buy, you should wash it before you eat it. Even if no pesticides were ever used on your food, your fruits and vegetables were grown in dirt, have almost certainly come into contact with something’s poop, and have been handled by several sets of hands. E. coli is organic, but you don’t want to eat it. Finally, this discussion pertains to organic produce only, not to organic meat, eggs, and dairy. There are some good reasons (discussed elsewhere) for going organic for these products.

SUMMARY

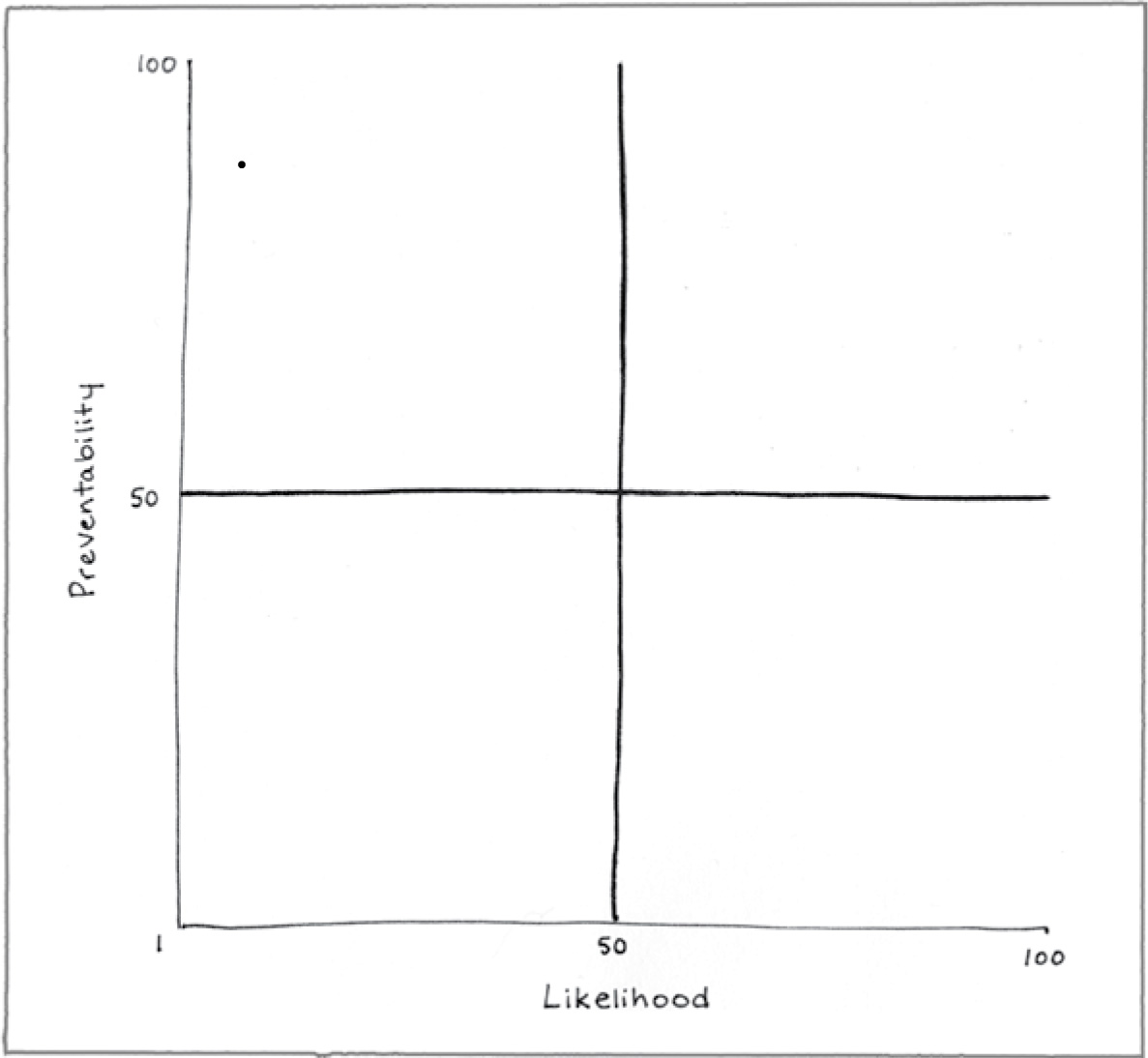

Preventability (91)

If you can afford it, you can buy the organic version of almost everything.

Likelihood (3)

You are very unlikely to suffer negative health outcomes from eating conventionally grown produce.

Consequence (2)

Pesticides and fertilizers can have negative consequences for farmers and for the environment, but they are unlikely to affect consumers. In addition, buying organic produce doesn’t mean that no pesticides and fertilizers were used in crop production.

REFERENCES

Betarbet, R., Sherer, T. B., MacKenzie, G., Garcia-Osuna, M., Panov, A. V., & Greenamyre, J. T. (2000). Chronic systemic pesticide exposure reproduces features of Parkinson’s disease. Nature Neuroscience, 3, 1301.

Brantsæter, A. L., Ydersbond, T. A., Hoppin, J. A., Haugen, M., & Meltzer, H. M. (2017). Organic food in the diet: Exposure and health implications. Annual Review of Public Health, 38, 295–313.

Coats, J. R. (1994). Risks from natural versus synthetic insecticides. Annual Review of Entomology, 39, 489–515.

Food Safety News. (2016, December 23). Few pesticide worries in latest California sampling data. Retrieved from http://www.foodsafetynews.com/2016/12/no-pesticide-worries-in-latest-california-sampling-data/#.WL-aizsrIvg

Hartmann, M., Frey, B., Mayer, J., Mäder, P., & Widmer, F. (2015). Distinct soil microbial diversity under long-term organic and conventional farming. ISME Journal, 9, 1177.

Lotter, D. W. (2003). Organic agriculture. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture, 21, 59–128.

Magkos, F., Arvaniti, F., & Zampelas, A. (2006). Organic food: Buying more safety or just peace of mind? A critical review of the literature. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 46, 23–56.

Moyer, M. W. (2014, January 28). Organic shmorganic. Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/double_x/the_kids/2014/01/organic_vs_conventional_produce_for_kids_you_don_t_need_to_fear_pesticides.html

Reeser, D. (2013, April 10). Natural versus synthetic chemicals is a gray matter. Scientific American Blog. Retrieved from https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/natural-vs-synthetic-chemicals-is-a-gray-matter/

Reganold, J. P., & Wachter, J. M. (2016). Organic agriculture in the twenty-first century. Nature Plants, 2, 15221.

Seufert, V., & Ramankutty, N. (2017). Many shades of gray: The context-dependent performance of organic agriculture. Science Advances, 3(3), e1602638, doi:10.1126/sciadv.1602638

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (n.d.). Organic standards. Retrieved from https://www.ams.usda.gov/grades-standards/organic-standards

Wilcox, C. (2012, September 24). Are lower pesticide residues a good reason to buy organic? Probably not. Scientific American Blog. Retrieved from https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/science-sushi/pesticides-food-fears/