9. SALT

In chemistry, a salt is a compound that is formed when you neutralize a negatively charged molecule (an acid) with a positively charged molecule (a base). Examples include potassium chloride, which is used in fertilizer; magnesium sulfate, which is used to soothe sore muscles; and sodium cyanide, which is a rapidly acting poison. However, when most of us talk about salt we’re referring to a particular compound—sodium chloride.

Sodium chloride is found in seawater, in crystal deposits, and in your salt shaker. Table salt, kosher salt, fleur de sel, and Himalayan pink salt are all primarily sodium chloride. Salt is useful for all sorts of things. It is a good cleaner, de-ices sidewalks and roadways, raises the boiling point of water, puts out fires, soothes a sore throat, and preserves food in the absence of refrigeration. Oh, and it enhances the flavor of food.

Salt boosts flavors because you have specialized cells in your mouth that respond to sodium. Along with sweet, sour, bitter, and savory (umami), salty is one of the five basic qualities of taste. A little bit of salt tastes good, and it makes other things, even sweet things, taste better. You may have special sodium detectors on your tongue because, physiologically speaking, sodium is very important to you. It is, in fact, very important to all animals, possibly because it is a major component of seawater.

Sodium, chloride, and potassium are the electrolytes primarily involved in the cellular resting membrane potential. The resting membrane potential is the result of different concentrations of these charged particles on the inside and the outside of the cell; sodium and chloride are relatively abundant in the extracellular space whereas potassium is relatively abundant in the intracellular space. These concentration differences lead to the inside of the cell having a negative charge with respect to the outside. This is important for nervous, muscular, and cardiovascular function. A full discussion of the membrane potential and how it works is beyond the scope of this chapter, but suffice it to say, it is very, very important, and the body spends a lot of energy maintaining it. Because sodium is abundant in the extracellular space (outside cells), it is very important in determining blood pressure and volume. As a result, the body tightly regulates sodium concentrations via the kidneys.

So, you need to eat some salt. According to the U.S. Institute of Medicine (IOM), if you are a moderately active adult, you need to consume about 1.5 grams of sodium every day. This will compensate for the salt you lose through sweat and elimination. The good news is, basically everyone is eating enough salt. The bad news is, we’re actually eating way more than enough. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Americans eat 3.4 grams of sodium per day.

Our level of salt intake is a problem because excessive salt is probably bad for our health. This is not news. Americans have been hearing, and ignoring, the warning that salt causes hypertension (high blood pressure) and cardiovascular disease for decades. The newsier part of this is the “probably.” For many years, the public health mantra has been that we should get our sodium intake down to 1.5–2.3 grams per day. This recommendation is based on a great deal of research showing a positive relationship between higher levels of sodium consumption and hypertension and cardiovascular disease. But the real health benefits of cutting back on salt are difficult to measure, partly because individuals respond differently to sodium. Salt sensitivity varies between people, which is to say that some people will see a greater difference in blood pressure in response to sodium intake than others. This variability is attributable to a number of different factors including genetics, environment, and sex. What’s more, the evidence for the current sodium recommendations is somewhat sparse. A 2013 report by the IOM (“Sodium intake in populations: Assessment of evidence”) found that while the effort to lower excessive sodium intake was appropriate, the evidence did not support lowering the recommended daily intake to 1.5 grams per day. They further commented that it would be difficult to make recommendations about a target sodium intake range for the general population. In addition, while most studies support the relationship between elevated sodium consumption and adverse cardiovascular events, some studies conflict. Notably, a large international study published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2014 (“Urinary Sodium and Potassium Excretion, Mortality, and Cardiovascular Events”) found the lowest risk of death and cardiovascular events for a consumption level of between 3 and 6 grams of sodium per day. People consuming more or less than that amount increased their overall risk. Nevertheless, most health agencies (for example, the National Heart Association and the CDC) maintain that the totality of the evidence favors a reduction in salt.

It probably won’t hurt you, and will likely help you, to cut back on your dietary salt. If you’re looking to reduce your sodium intake, you’re going to need to pay attention to labels, because salt can be found in some surprising places. Most of the salt in our diets doesn’t come from the salt shaker; it comes from processed foods. Bread, cereal, condiments, canned goods, lunch meats, and cheese are all high in salt. A sandwich can be a serious salt bomb. The good news/bad news on that front is that it is a good idea to cut back on processed foods anyway. Eating more fresh vegetables, beans, and (unsalted) nuts is likely to do you good on a number of fronts.

On a side note, potassium intake is also related to hypertension—but unlike sodium, it is inversely related. Good news! Those low-sodium fruits and veggies are often high in potassium.

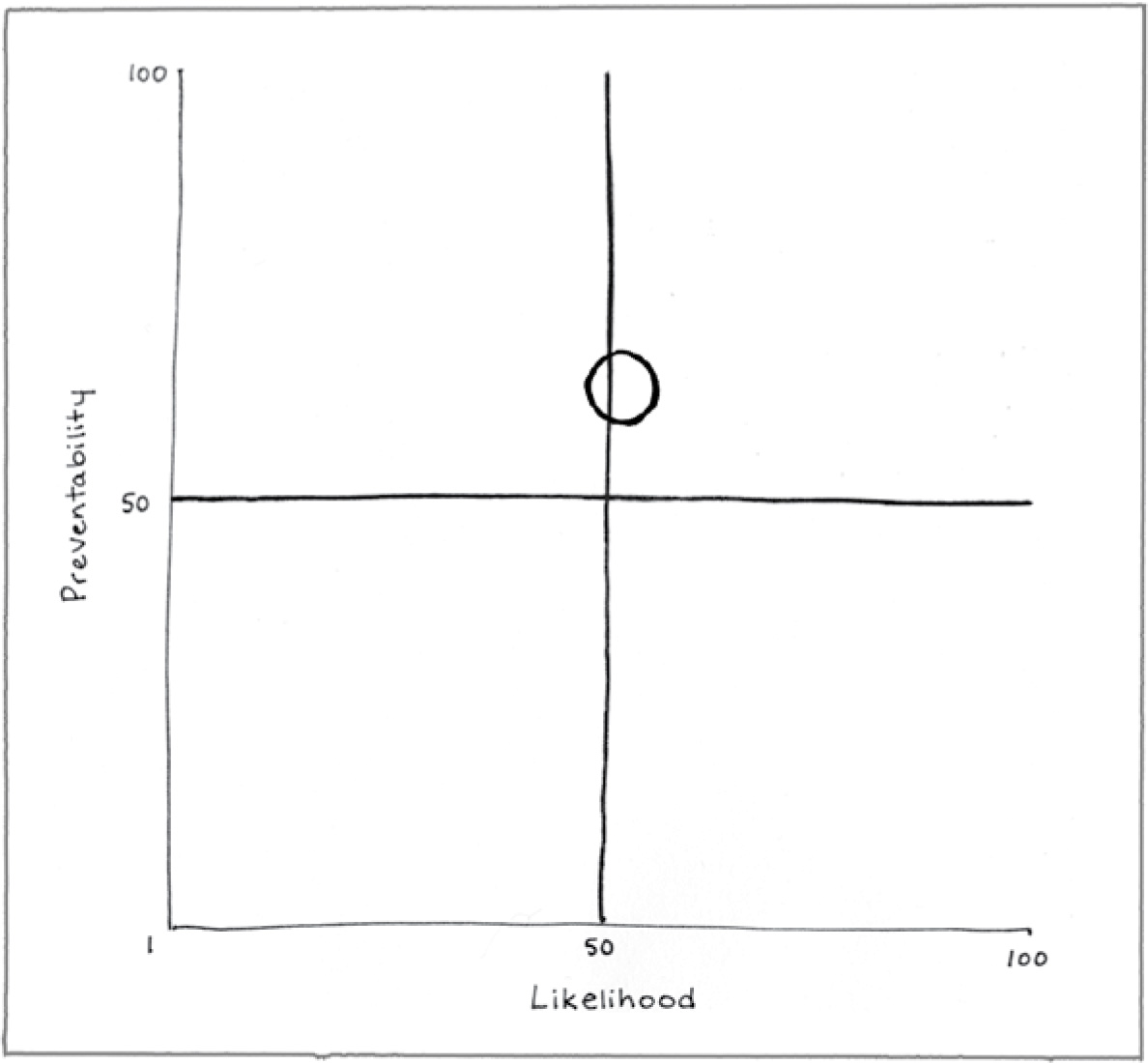

Preventability (63)

You can make a conscious effort to reduce your salt intake, but it is a very common food additive.

Likelihood (51)

The weight of the evidence suggests that consuming excess salt is likely to have adverse health effects.

Consequence (60)

High blood pressure is a serious risk factor for cardiovascular disease. It is common, but not trivial.

Aaron, K. J., & Sanders, P. W. (2013). Role of dietary salt and potassium intake in cardiovascular health and disease: A review of the evidence. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 88, 987–995.

American Heart Association. (2017, April 21). Sodium and salt. Retrieved from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/HealthyLiving/HealthyEating/Nutrition/Sodium-and-Salt_UCM_303290_Article.jsp#.WZpsblGGPZv

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2017, October 18). Sodium and the National Academies of Science (NAS) Health and Medical Division (HMD). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/salt/sodium_iom.htm

Institute of Medicine. (2013). Sodium intake in populations: Assessment of evidence. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from https://www.nap.edu/read/18311/chapter/2

National Institutes of Health. (2010, February 12). Salt taste cells identified. Retrieved from https://www.nih.gov/news-events/nih-research-matters/salt-taste-cells-identified

O’Donnell, M., Mente, A., Rangarajan, S., McQueen, M. J., Wang, X., Liu, L., . . . Yusuf, S.; PURE Investigators. (2014). Urinary sodium and potassium excretion, mortality, and cardiovascular events. New England Journal of Medicine, 371, 612–623.

Oh, Y. S., Appel, L. J., Galis, Z. S., Hafler, D. A., He, J., Hernandez, A. L., . . . Harrison, D. G. (2016). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group report on salt in human health and sickness: Building on the current scientific evidence. Hypertension, 68, 281–288.

Wenner, M. (2011, July 8). It’s time to end the war on salt. Scientific American. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/its-time-to-end-the-war-on-salt/

Whoriskey, P. (2015, April 6). Is the American diet too salty? Scientists challenge the longstanding government warning. Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/04/06/more-scientists-doubt-salt-is-as-bad-for-you-as-the-government-says/?utm_term=.960d2ce4e4b3