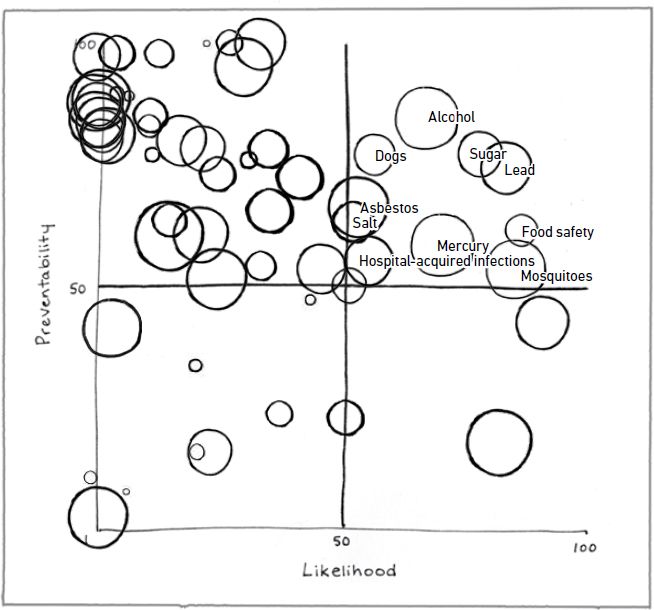

In this book we have reviewed a number of issues that you might reasonably choose to worry about. We have done this with the express goal of understanding what is and what is not worth the burden of concern you might put into it. As part of this exercise we have assigned a worry index to each topic, although, as we have gone to some lengths to point out, these are just our own estimates and not a rigorously defined scale. Nevertheless, we think they provide an interesting starting point for weighing the relative risks of these subjects. Because humans (like most primates) are quite visual, it is often easier to understand data in graphic form. Therefore, we have presented a plot in each chapter representing the worry index in three dimensions: preventability, likelihood, and consequence.

Now that we have done the hard work of assigning a score to each entry, we present the combined graph that shows how the worry indexes for each topic compare to each other. As you may recall, in our opinion, the things most worth worrying about are those which (a) are likely to happen, (b) will be serious if they do happen, and (c) can be prevented by some action on your part. Addressing these topics will make the biggest difference for the least effort. These most worry-warranting items show up as large circles in the top right quadrant of the graph. Because they are the most important, we have labeled them.

You may be surprised by the topics in the “recommended to worry about” zone. With the possible exception of hospital-acquired infections, there is nothing on the list that most of us didn’t already know about. Because they are so familiar, however, we may not be giving them the level of attention that they deserve. Many people are worried about snakes, but for most of us, dog bites are a much more pressing concern. Likewise, as a society we have a very cavalier attitude about alcohol. But drinking can have very serious consequences. And, critically, these consequences are highly preventable. Sugar and lead (both sweet!) also rank high on the worry scale. You probably already knew you needed to worry about these issues, but they might not seem as urgent as they really are. In some ways, the lack of novelty in the top-ranking worry issues can be sort of a letdown. It’s a bit of an anticlimax to hear, again, that you need to watch your salt, sugar, and alcohol intake. All we can say is that we sympathize with you.

If you’re feeling let down by the top right quadrant, there are some interesting features in other quadrants. For example, the bottom right section of the graph has two big scary circles. These correspond to antibiotics in feed animals and medical errors. What makes these issues so troubling is that they are likely to happen, the consequences can be very serious, and you can’t do much to stop them. We recommend that you do not spend your time and attention on these issues exactly because you can’t do much about them. But we freely admit that there isn’t much comfort there.

Another interesting feature is what we refer to as the zone of uncertainty. As it happens, for some subjects the risks are poorly characterized, either because the data don’t exist or because different studies have produced conflicting results. In these cases, we have assigned a score of 50. It seems wrong to say that you shouldn’t worry about some of these things, because they could be quite dangerous. On the other hand, if the potential to harm hasn’t been proven, it seems irresponsible to stir up anxiety. This is exemplified by BPA, which we have given a score of 50, 50, 50, and which appears smack dab in the middle of the chart.

The best news about this plot is that most of the points fall on the left-hand side. That means they are unlikely to cause you any problems (as long as you are the average person in each case). This might be because we have chosen a very skewed distribution of topics to review. Perhaps if we had chosen different topics, we would have seen a different result. But another likely explanation is that there aren’t as many things to worry about as we tend to imagine. At least, not as many things in the category of topics that we have focused on in this book.

It is worth pointing out that all of the topics addressed in this book are higher-order issues. That is to say, they are only the sorts of things that you worry about when all of your more fundamental needs are being met. You only think about BPA leaching into your food when you have enough food, and you only worry about flame retardants in your mattress when you have a mattress to sleep on. So if you have the opportunity to worry about these things at all, you are in a privileged position. This is not to say that these issues are trivial or not worth considering, only that they should be considered in perspective.

This actually takes us in a bit of a philosophical direction. We have optimized worrying in a way that makes sense to us. But you should not take this at face value. Instead, take some time to consider what your priorities are for your life. It is natural (and good) to want to minimize personal pain and suffering, and to prolong your life span. The instinct to survive and to protect our loved ones is important. However, sooner or later we will all have to confront the fact that no matter how careful we are, immortality is unachievable.

We are living in a unique time in human history, which means we have unique problems that our ancestors never had to deal with. In centuries past, no one had to worry about PFAs or GMOs or artificial coloring in their food. There is a temptation to look back on those times and imagine that they were better. We romanticize the simplicity of the past, and in some ways maybe it was better. But in many meaningful respects it wasn’t. People didn’t live as long, and they didn’t live as well. They didn’t have as many choices, and they didn’t have as much information with which to make choices. They didn’t worry about exposure to pesticides, but they could be driven to starvation by locusts. They didn’t get hospital-acquired infections because there were no hospitals; if you could afford to get medical treatment, you were likely to be prescribed elemental mercury. The world is a dangerous and worrisome place, but it always has been. That is just part of the human condition.

This being the case, how do you want to balance quality of life with quantity of life? Worrying about things will cost you time, effort, stress, and often money. Is it worth it? How do you want to spend your limited life resources? Clearly, there is no one right answer to this question. But there is an argument to be made that, in addition to making you stressed out and sick, worrying about small things can distract you from worrying about life’s major issues like finding a purpose, finding love, and learning to forgive. Unfortunately, we can’t help you with that; you’re going to have to find a different book.

This book is about navigating life’s everyday hazards, and on that, we can offer some advice. During the writing of this book we repeatedly came across the same advice in different contexts. It turns out there are some simple practices that will help you to minimize your risk on several fronts simultaneously. Adopting these habits will kill multiple (figurative) birds with one stone:

- Wash your hands frequently.

- Eat fewer processed foods.

- Eat more vegetables.

- Keep the dust down in your home.

- Read and follow directions.

- Communicate extensively with your physician.

Finally, if you come across something disturbing, don’t worry about it—do something about it.