Later in the year, when decisions were made about the disposition of lands, property, and prisoners in the wake of the Dakota War, much would be made of the great distance between the East and the Northwest. As questions of justice, vengeance, and mercy were laid at the feet of politicians, administrators, and lawyers in Washington, D.C., a cry would go up along the frontier that weak-willed strangers were making decisions about people they’d never met and places they’d never seen. And it was true that Abraham Lincoln had never set foot in Minnesota. But the pervasive feeling of Minnesotans that they were dealing with distant and uninformed observers was, in the end, unfounded. The number of federal officials in Minnesota during the six weeks of the Dakota War would come to include not only lawyers and soldiers, but the commissioner of Indian affairs, the assistant to the secretary of the interior, and a prominent Union major general. Each in his own way had the ear of the president, and each would provide important information and counsel. But no observer in Minnesota during the fall and winter of 1862 was closer to Abraham Lincoln, personally and professionally, than his personal secretary John G. Nicolay, the dour young German with the pronounced slouch who disembarked in Saint Paul on August 22, just four days after the Dakota War began.

Nicolay’s presence, and by extension the administration’s, would come to have dramatic consequences for the Dakota and their white adversaries, but it was also entirely coincidental. Fifty miles northwest of the Upper Agency lay two picturesque bodies of water, Big Stone Lake and, to the north, Lake Traverse, between which a narrow gap of prairie marsh made a bountiful home for geese, ducks, egrets, and herons. Across this gap of land passed the continental divide, so that the waters of Big Stone Lake emptied into the Minnesota River, bound for the Gulf of Mexico, while those of Lake Traverse flowed in the other direction as the Red River of the North, heading for Lake Winnipeg and Hudson Bay, marking the border between the state of Minnesota and the Dakota Territory along the way.

The Red River’s broad valley, flat as a tabletop, was the last quadrant of the state undivided into white lands and reservations, and this summer the Lincoln administration was determined to rectify the situation. As unrest among the Dakota at the Upper Agency began to boil over in early August, a group of federal officials had assembled in Saint Paul to head north and open negotiations with the Ojibwe bands at Pembina, an old fur-trading center on the west side of the Red River near the Canadian border. Among them were Commissioner of Indian Affairs William P. Dole, Northern Division superintendent Clark W. Thompson, several military escorts, and Nicolay.

Nicolay’s daughter, Helen, wrote later that Lincoln “occasionally found it convenient to have an unprejudiced observer at some distant point” during treaty negotiations, without including any hint as to whether or how her father’s traveling companions on this expedition, all members of the executive branch, had been deemed not unprejudiced. Whatever reasons existed to keep an extra pair of eyes on the treaty’s progress, Nicolay was a reliable man whose loyalty to the president was as strong and impenetrable as steel. He and assistant secretary John Hay were Lincoln’s most trustworthy employees, a pair of hand-picked young men who were utter opposites in temperament but who shared a partiality to backstairs gossip, a belief in their employer’s superiority to every other person in the world, and a consuming love of their day-to-day work.

Nicolay had entered the future president’s orbit at the age of twenty-four, in 1856, when he was a precocious young editor at the Pike County Free Press. Lincoln delivered a speech in Pittsfield, Illinois, in support of his Senate campaign and visited Nicolay’s office, where the two struck up a conversation that would change Nicolay’s life forever. Nicolay’s influence exceeded his years and his short tenure on the newspaper. He had helped to create the Illinois Republican Party, grounding its platform on a hatred of slavery that nevertheless stopped short of a call for abolition. In 1857, he began clerking for Illinois secretary of state Ozias M. Hatch, and three years after that, as the Chicago presidential nominating convention approached, he published a widely read editorial comparing Lincoln with Lincoln’s hero Henry Clay, an article that the future president himself may have suggested or even written. In need of a private secretary following his nomination, Lincoln had asked Hatch for a recommendation, and Nicolay’s name was the only response.

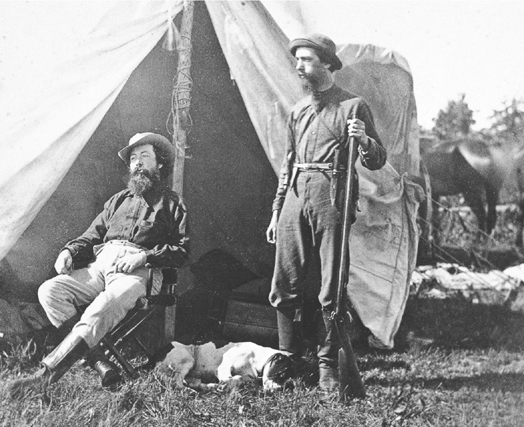

An orphan who had emigrated from Germany in 1838 at the age of six, Nicolay soon came to see Lincoln as a surrogate father. The “sour and crusty” half of the Nicolay-Hay tandem, Nicolay was trim and slump-shouldered with a whopping mustache, a man whom the Philadelphia Press editor John Russell Young described as “scrupulous, polite, calm, obliging, with the gift of hearing other people talk.” Assistant Secretary William O. Stoddard called Nicolay “a fair French and German scholar, with some ability as a writer and much natural acuteness,” who “nevertheless—thanks to a dyspeptic tendency—had developed an artificial manner the reverse of ‘popular,’ and could say ‘no’ about as disagreeably as any man I ever knew.” The contrast with the rakish, fraternal Hay, who loved to tell long jokes and had been named Class Poet on his graduation from Brown University, made them the capital’s strangest, if most efficient, duo.

In preparation for his visit to the Northwest, Nicolay had read Edward D. Neill’s History of Minnesota while riding the train to Chicago. A Presbyterian cleric, native Pennsylvanian, and graduate of Amherst, Neill was also an amateur historian who wrote in a sort of provincial sublime, announcing his purpose to “show where Minnesota is, its characteristics and adaptations for a dense and robust population, and then consider the past and present dwellers on the soil.” Published in 1858, the year of the state’s birth, the book was actually a history of the ground from which the state had emerged and a love letter to its future. Minnesota’s destiny was indeed manifest, Neill believed, as was the moral superiority its natural wonders imparted upon its residents: “Grand scenery, leaping waters, and a bracing atmosphere, produce men of different cast from those who dwell where the land is on a dead level, and where the streams are all sluggards.”

Presumably Nicolay was most interested in the sections regarding the Ojibwe tribe, or the Chippewa as whites called them. Much of Neill’s information related to “the aborigines” came courtesy of his fellow Presbyterians Stephen R. Riggs, Samuel Pond, and Thomas S. Williamson, and was limited to the Dakota bands; unlike these men, however, Neill was full of undisguised disdain for almost all Indians. “Like all ignorant and barbarous people, they have but little reflection beyond that necessary to gratify the pleasure of revenge and of the appetite,” he wrote. “While there are exceptions, the general characteristics of the Dahkotahs, and all Indians, are indolence, impurity, and indifference to the future.”

In these sentiments Neill may have found a sympathetic reader. Helen Nicolay, in her biography of her father, wrote that Nicolay “entertained no sentimental illusions about the North American Indians. He had grown up too near frontier times in Illinois to regard them as other than cruel and savage enemies whose moral code (granted they had one) was different from that of whites.” Perhaps Nicolay or his family had once known Indians as close‑up adversaries, but the letters he exchanged with John Hay during his month away reveal two entrenched easterners’ patronizing view of the frontier. “If in the wild woods you scrounge an Indian damsel,” Hay wrote shortly after Nicolay’s arrival, “steal her moccasins while she sleeps and bring them to me.” This was typical Hay, whose contemporaneous writings sometimes made the running of the government sound like a schoolboy’s lark. Nicolay, the far more serious of the two, enjoyed the banter, but he was in Minnesota for real work, hoping to help the Interior Department clean up a lingering mess without making any new ones.

In 1659 the Ojibwe had moved onto the edge of Dakota territory, along the south shore of Lake Superior, beginning many decades of tribal diplomacy and trade in furs, weapons, cooking implements, and other goods, accompanied by the occasional skirmish between hunting parties. In 1737 that skirmishing erupted into war as the Ojibwe pushed up to and across the Mississippi River, scoring the landscape with battle until the tribes settled into their eighteenth-century homes, the Ojibwe in the northern pine woods and lake districts of the Northwest Territory, the Dakota along the lower Mississippi and Minnesota River valleys and farther west, with only the hunting grounds of the Big Woods and Saint Croix River Valley remaining in dispute. Contests once fought between hundreds of warriors on a side now involved groups of five, ten, or twenty Indians raiding in competition for game, over trading rights, or in actions designed to bring a warrior honor or glory. Two might die, or twelve. The warfare was violent and quick, often performed by ambush, and sometimes women and children were the victims, snaring ever wider kinship networks in a thickly woven net of self-perpetuating feuds.

All the while the United States had increased its presence in the region, building Fort Snelling in 1819 on a small cession of Dakota land, gathering Dakota and Ojibwe leaders for a peace conference in 1825, and making a long series of separate treaties with the two tribes that, by 1862, left only the Red Lake and Red River Valley Indians on unceded lands. Like the Dakota, the Ojibwe lived in several autonomous bands and did not hold council as one people, but as one people they had ample reason to be suspicious of the motives and faith of the U.S. government. In 1850, twelve years earlier, Alexander Ramsey, then the territorial governor, had traveled north to achieve what he thought would be the accomplishment of his lifetime, bringing the Ojibwe from Michigan and Wisconsin into the Minnesota Territory and keeping them there by way of a simple ruse: Orlando Brown, commissioner of Indian affairs under Zachary Taylor, declared that the annuity payment was to be distributed in a new place—Sandy Lake, one hundred miles north of Saint Paul—so late in the autumn that the return trip to their homelands would be impossible, all to satisfy white hopes of speeding westward removal of the Ojibwe while drawing the treaty gold and its associated bounty into the Minnesota Territory, where it would benefit Minnesota’s traders, contractors, and politicians.

The plan was a success, at least until news of heartbreak and destitution among the stranded Indians reached the Saint Paul newspapers. Breathless and entirely fabricated reports of cannibalism, side by side with more sober and accurate accounts of spoiled flour, rotten pork, measles, dysentery, and frostbite, generated enough attention among whites, if not anger, that the scheme collapsed. The following spring President Taylor canceled a standing removal order and allowed the eastern Ojibwe to return to their homes, ending an ordeal that left hundreds of Indians dead. Unabashed, Ramsey turned his attention to treaty-making with Little Crow and the other Dakota, whose land was far more attractive to immigrant farmers, and left the Ojibwe to a future generation of political leadership.

Now, as it turned out, “Bluff Alec” himself, returned to political prominence, was that generation of leadership. And so Nicolay and the others headed to the Northwest, hoping to sew the final loose piece of Minnesota into the white American quilt.

After arriving in Saint Paul early in August 1862—even as Henry Whipple and Sarah Wakefield were observing the unrest among the Dakota at the Upper Agency—Nicolay had written to his family that the city “seemed to him ‘primitive,’ and the International Hotel smelled strongly of pine and kerosene, but the week he spent there was so filled with pleasant excursions that he pronounced the region ideal for summer residence ‘provided of course one has wealth and leisure.’ ” Here he had rendezvoused with Commissioner Dole, Superintendent Thompson, and Minnesota senator Morton Wilkinson. Together they steamed up the Mississippi to a small river town called Saint Cloud, built on old Ho-Chunk lands, where they prepared to go west, planning to follow an oxcart trail over the prairie to Fort Abercrombie on the Red River of the North, a hundred miles south of Pembina. Before their party could depart, however, they received strange, unsettling news when Ojibwe agent Lucius C. Walker ran into town in a panic, reporting that hundreds of Ojibwe warriors were gathering upriver at Gull Lake. Their purpose, according to Walker, was to attack the whites at the nearby Ojibwe agency and then move on to capture Fort Ripley just below, with Saint Cloud squarely in their sights.

Walker’s most dire predictions would soon turn out to be baseless, but, as Nicolay wrote, “[t]he whole border at once took alarm. The settlers gathered up their guns and weapons, barricaded their doors and windows, and packed up their movables, to be ready to leave at a moment’s warning.” The next day, August 20, the news worsened when bits and pieces of talk about the attack on the Lower Agency reached Saint Cloud, prompting Nicolay’s party to cancel its plans. Families sought shelter in the town’s sturdiest brick buildings, and men began to throw up fences and build blockhouses. Patrols went out that night to the north and south of the town and on both sides of the Mississippi River. Meanwhile, the Ojibwe agent snapped. As Nicolay reported, Walker fled “at break-neck speed down the Mississippi, crossing and recrossing the river, and intensifying the panic by telling wild and incoherent stories that the [Ojibwe] were not only pursuing him, but attacking the settlements.”

Returning to Saint Paul on August 22, Nicolay, Dole, and their companions huddled with Governor Ramsey and other state officials to repeat Walker’s warnings and to hear all of the details of the Dakota War, now four days old: hundreds dead in the settlements, hundreds more taken captive, assaults on Fort Ridgely and New Ulm. What they’d been told in Saint Cloud had not been the half of it. Several companies of soldiers had been dispatched from Fort Snelling to the Minnesota River Valley, and more were gathering in the riverside towns along the way, waiting on weapons and ammunition. To the southwest lay only war against the Dakota, but the Ojibwe up north were another matter. They might or might not have been “on the warpath,” as the Indian agent believed, but no concerted attacks had occurred, and there was plenty of reason to believe peace might still be possible. Nicolay would be going north to act as Lincoln’s eyes and ears after all, even if the negotiations would be of a very different sort than he’d anticipated.

Governor Alexander Ramsey’s next message to Edwin Stanton was dated 2:30 p.m. on August 25, the day the Dakota began to retreat from New Ulm along the river valley. It began with a nudge. “The Indian war is still progressing,” he wrote. “The panic among the people has depopulated whole counties, and in view of this I ask that there be one month added to the several dates of your previous orders for volunteers, drafts, etc.—22d August be 22d September, 1st September be 1st October, 3d September be 3d October. In view of the distracted condition of the country, this is absolutely necessary.”

The message came with a postscript written and signed by Commissioner Dole: “I have a full knowledge of all the facts, and I urge a concurrence in this request.” In the federal chain of command in the midst of the Civil War, the commissioner of Indian affairs, subordinate to the secretary of the interior, ranked far below the secretary of war. Dole’s urging was not likely to impress War Secretary Edwin Stanton much, and Stanton replied in the negative later that day. But no longer was Minnesota one petitioner among all of the others clamoring for attention; with Dole and Nicolay in Saint Paul, the state had a direct line to Lincoln and a way to use it. Now the executive branch was, implicitly and explicitly, speaking with itself.

They would need that direct line, because the Union’s call for additional volunteers had come from the White House and thus only the president could approve an extension. Less populous than Rhode Island, Minnesota had already contributed two companies of sharpshooters, three of cavalry, two artillery batteries, and five full regiments of infantry; it was in the process of filling a sixth regiment in July when Lincoln called for 300,000 more soldiers. The state’s proportional quota was 5,360 new men, or close to six more regiments, doubling the number it had already sent. In a state with no more than 200,000 people, the fraction of able-bodied young men, white and mixed-blood, was small and shrinking, so all of the patriotic machinery—bands, banners, picnics, speakers, and sermons—had begun to hum once more. Volunteerism and morale were high, but not high enough to populate the military units required for two wars.

Ramsey was not done making attention-getting requests. The next day, August 26, he wired Henry W. Halleck, Lincoln’s general in chief, asking him to create a federal military department in the Northwest so that Union officers, supplies, and funds might be made available to take part in the Dakota War. Later that evening Halleck replied in one sentence that no such department was forthcoming. At ten o’clock, finally, Ramsey put Lincoln’s name on a telegram, the first communication of the Dakota War addressed directly to the president. The governor’s message made it plain that every word he’d sent over the past forty-eight hours had been written in conference with Dole as, presumably, Nicolay looked on. “With the concurrence of Commissioner Dole,” Ramsey wrote, “I have telegraphed the Secretary of War for an extension of one month of drafting, etc. The Indian outbreak has come upon us suddenly. Half the population of the state are fugitives. It is absolutely impossible that we should proceed. The Secretary of War denies our request. I appeal to you, and ask for an immediate answer. No one not here can conceive the panic in the state.”

Lincoln did not provide an immediate answer, so the next morning Nicolay finally stepped out from behind the men who outranked him and found the success none of them had managed. Later that day their peace-making party would steam back up the Mississippi River to seek terms with the Ojibwe, but at 10:30 a.m. they were handing the Saint Paul telegraph operator a message “to the President of the United States” signed by Nicolay, Dole, and Senator Wilkinson: “We are in the midst of a most terrible and exciting Indian War. Thus far the massacre of innocent white settlers has been fearful. A wild panic prevails in nearly one-half of the state. All are rushing to the frontier to defend settlers.”

Ramsey had already wired Lincoln directly, and Nicolay’s message contained no request and no information that hadn’t already been communicated; it was intended only to get the president’s notice and nothing more. Nicolay also sent a much longer telegram to Edwin Stanton.

The Indian war grows more extensive. The Sioux, numbering perhaps 2,000 warriors, are striking along a line of scattered frontier settlements of 200 miles, having already massacred several hundred whites, and the settlers of the whole border are in panic and flight, leaving their harvest to waste in the field, as I have myself seen even in neighborhoods where there is no danger. The Chippewas, a thousand warriors strong, are turbulent and threatening, and the Winnebagoes are suspected of hostile intent. The Governor is sending all available forces to the protection of the frontier, and organizing the militia, regular and irregular, to fight and restore confidence.

“As against the Sioux, it must be a war of extermination,” Nicolay added. This was the first public mention of “extermination” by any government official, but as Alexander Ramsey would soon prove very fond of the word, one suspects it had been often used in private during the previous week. Given his reputation for stoicism and understatement, Nicolay’s message that a major Indian war was brewing was guaranteed to raise eyebrows, along with his suggestion that Stanton accede to Ramsey’s request for 1,200 cavalry, 6,000 guns, a half-million cartridges, blankets for 3,000 people, and medical supplies for three regiments.

Nicolay’s telegrams finally did the trick. Lincoln’s attention was, for the first time, engaged. The president’s response arrived later that day and was addressed, tellingly, to the governor. “Yours received. Attend to the Indians. If the draft cannot proceed of course it will not proceed. Necessity knows no law. The Government cannot extend the time.” Even after multiple readings, these sentences seemed to hold open-ended, even contradictory meanings, but Nicolay had drafted hundreds of such telegrams and notes from the president himself and he, at least, would have known how to read them. The message was stated, the understanding absorbed. They were free to hold back men in Minnesota, but not to invoke Lincoln’s name in doing so. “Attend to the Indians” they would.

On Monday, August 25, the same day that Little Crow began his retreat up the Minnesota River Valley and Ramsey sent his second telegram east with Commissioner Dole’s brief addendum, Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune published two extraordinary items. Placed side by side on the front page, one would be remembered forever and the other forgotten in a matter of days. The first was the president’s reply to Greeley’s “Prayer of Twenty Millions.” The piece had been published a few days earlier in the capital’s foremost paper, the National Intelligencer, in the sure knowledge that Greeley would reprint it, perhaps a little quid pro quo for the original preemptory appearance of the “Prayer.” Greeley didn’t care, of course; he published the response happily, no doubt anticipating a bump in sales and appreciating the testament to his own national influence.

Frank, precise, and designed to please no one in particular, Lincoln’s answer to Greeley’s challenge has come down through history as one of his most important statements. He began with some personal needling: “If there be in [Greeley’s ‘Prayer’] any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptible in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.” Then he got down to brass tacks, reminding Greeley and the nation that his loyalty lay with the Union above all else.

If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.

The third of these options was about to become government policy, sitting on his desk even now in the form of a draft of the Emancipation Proclamation, but that document had not yet been made public and Lincoln would not let Greeley and his fellow editors hound him into doing so before he was ready. The president closed his response with a small sop to abolitionists, writing that he intended “no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free,” but the message had been delivered: when it came to measures as dramatic as emancipation, Lincoln would consult his own schedule and take his own counsel.

One column over from the words PRESIDENT LINCOLN’S LETTER was its companion headline, INDIAN MURDERS, below which were 540 of the strangest, least useful words Greeley ever published. Over the past week the paper had reprinted two brief early dispatches from the Dakota War, one labeled ATTACK ON THE WHITES and the second THE INDIAN TROUBLES IN MINNESOTA. Now, only six days into the conflict and with no particular intelligence in hand, the Tribune was ready to name its underlying cause. The first two-thirds of Greeley’s editorial focused on Confederate appeals to “foreign aid” and efforts to enlist Cherokee troops in the Southern cause, efforts Greeley considered base hypocrisy in light of the fact that the South had “expelled most of those Indians from their original homes, in violation of the faith of treaties and in defiance of the earnest, protracted resistance of the loyal influences now predominant at the North.” He then offered a short and reasonably accurate summary of the circumvention of treaty provisions and Supreme Court decisions that had led to the Trail of Tears, before reasoning with dubious logic that the Cherokee practice of owning slaves explained their common cause with Jefferson Davis. This primer was only a preamble, however, to Greeley’s main point.

The new out-break in the North-West has manifestly a like origin, without a like excuse. The Sioux have doubtless been stimulated if not bribed to plunder and slaughter their White neighbors by White and Red villains sent among them for this purpose by the Secessionists. These perfectly understand that the Indians will be speedily crushed and probably destroyed as tribes; but what care their seducers for that? They will have effected a temporary diversion in favor of the Confederacy, and this is all their concern. But a day of reckoning for all these iniquities is at hand.

In other words, the Dakota could not possibly have a beef of their own. Nothing could exist outside of the conflict between North and South. As argument, this was shaky; as war correspondence, a failure. As an appreciation of the dissatisfactions and debasements behind the Dakota’s decision to go to war, it was wreathed in total ignorance. But as an expression of a growing national anxiety, it was spot on.

From the vantage point of officials in Washington, Alexander Ramsey’s initial telegram seemed the first shudder of a tectonic event. As if they had heard a single starting bell, military and political leaders in Iowa, Wisconsin, the Dakota Territory, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Colorado began to send alarming messages to the capital portraying a sudden increase in “unrest” and “agitation” among Indian tribes. No other violence during these autumn weeks approached the scale of the Dakota War, but now almost every foray by any tribe in the West—forays that were hardly a brand-new phenomenon—was given one simple explanation.

Brigadier General James Craig, at Fort Laramie in Wyoming, began the parade on August 23 by wiring about “Indians, from Minnesota to Pike’s Peak, and from Salt Lake to near Fort Kearney, committing many depredations” and adding later that he was “satisfied rebel agents have been at work among the Indians.” On the 30th, Craig reported on small-scale raids by Snakes and Blackfeet and recent skirmishes with Ute Indians and concluded “that some vicious influence is at work among the Indians is proved by the fact that there never was a time in the history of the country when so many tribes distant from and hostile to each other were exhibiting hostility to the whites.”

The telegrams piled up in the War Department, from military officers and Indian agents in multiple states and territories, from the governor of Iowa, and from William Jayne, once Lincoln’s personal physician and now governor of the Dakota Territory, all communicating some variation of the message sent by a Colonel Patrick of Nebraska: “The hostilities are so extensive as to indicate a combination of most of the tribes, and suggest the propriety of some action by the War Department.” Alexander Ramsey took to calling the Dakota hostilities a “national war,” and Greeley was not the only newspaperman to agree. Scientific American reported that “editors in the vicinity express the opinion that this rising of the Indians is the result of rebel machinations; the Indian war being designed to keep at home a considerable portion of the military force of the frontier states.”

No such “combination of most of the tribes” existed, however persistent and pernicious the belief would become. Indian alliances had been a fearsome wild card in every American war to date, and some exaggerated historical memory was at play. And the Civil War, like every other war, was conducive to conspiracies, real and imagined; as in every other war it was customary to view one’s opponent as nearly omnipotent and forever scheming. But Indians and whites had struck at one another for centuries, the intensity of conflict ebbing and flowing according to the pace and push of the American frontier’s advancing edge, and the Civil War era was no different. It was beyond the imagination of many that the grievances of various Indian tribes could be so similar and yet be nursed separately. What united the West, in fact, was not a confederation of Indians but rather the pervasive white fear of one.

By February of the following year the Lincoln administration would formally, if quietly, declare that the idea of a coordinated Indian offensive, planned and implemented by a network of Southern agents, was pure fantasy. Many of those most responsible for spreading the idea would issue personal mea culpas as the Union came to understand how much the South was hampered by limitations of manpower, industrial capability, and geography. But at this moment no one seemed to know how much Northern manpower would now be needed west of the Mississippi River to fight Indians, and novel solutions were in high demand.

As recently as August 23, Lincoln had refused to allow the enlistment of black troops in the Union army, at least until his Emancipation Proclamation could be announced. Two days later he changed his mind. The exact impetus for his change of mind is unknown, but August 25 was the very day that Governor Ramsey and Commissioner Dole asked for an extension of Minnesota’s draft quota and the day that officials in Wyoming and Nebraska wired Washington with their fears of a Confederate-led Indian uprising. Apparently, black soldiers would be useful after all.