Sarah Wakefield described the morning of August 26 as a “confusion of Babel” filled with instructions, rules, and warnings as two thousand Dakotas prepared to retreat from the Lower Agency with three hundred captives. “I wish it was within my power to describe that procession as it moved over the prairie,” she wrote. “I think it was five miles in length and one mile wide; the teams were very close together, and of every kind of vehicle that was ever manufactured.” Oxcarts, chaises, bakers’ carts, peddlers’ wagons, and coaches were festooned with American flags. Some of the Dakota decked themselves out for the journey in plundered dresses, bonnets, shawls, and jewelry, all forbidden to the captives but worn as trophies by their captors. Horses, dogs, and even a few cows followed along. Musical instruments sounded, many played inexpertly to hoots of laughter.

The first sight to greet the procession as it passed out of the Lower Agency and onto the reservation road in the morning was George Gleason’s body, still lying where Hapa had shot him. “He was stripped of his clothing, except his shirt and drawers,” Sarah wrote, “and his head had been crushed in by a stone.” They slept out on the prairie that night and the next, and on August 28 they arrived at the Upper Agency, where Sarah found her house emptied of every possession except its furniture. All of the agency buildings were now occupied by Sissetons and Wahpetons who had come in for protection and what forage and supplies could still be had. Little Crow went forward and met with these Dakotas to issue an ultimatum. He was not about to stay at the agency, so close to the white settlements and whatever white forces were now coming after him, but neither would he let those forces use the Upper Agency as a base. “These houses are large and strong and must be burned,” he said. “If you do not get out you will be burned with the buildings.” Get out they did, hitching their wagons and riding off a few hours ahead of the main body of Little Crow’s caravan.

Here Sarah wept as James was returned to her unharmed by his companions and protectors among Chaska’s kin, though she didn’t at first recognize her son in his Dakota dress. The boy’s spirits were high, his sense of adventure kindled by living apart from schoolbooks, daily schedules, and parental strictures. As the procession prepared to move again, Sarah, who spoke better than rudimentary Dakota, was able to provide news to the other captives who crossed her path. She also admonished some of them for making such a show of their unhappiness, telling one white woman that “she took a wrong course with the Indians, that they gave her the best they had, and she must try and be patient; that her life would be in danger if she kept on complaining and threatening them.” The same woman, Jannette De Camp, wife of the Lower Agency’s sawmill supervisor, told Sarah that she had heard one of her captors say that he had seen John Wakefield’s body, to which Sarah answered, “If that is so, I might as well pass the remainder of my days here as any place.” “Here” meant “with the Indians,” and it was not the last time during her captivity—or during her life—that she would make such a statement.

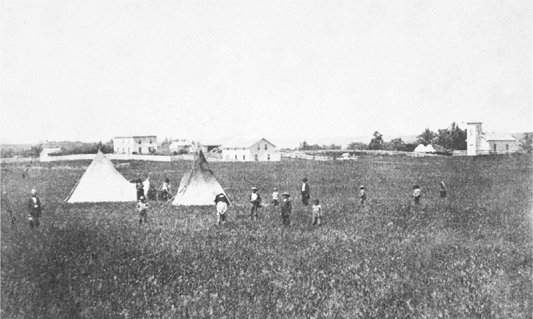

Her stay at the Upper Agency was short. As the procession moved away into the setting sun, Sarah watched with a sore heart as her house and the other buildings burned behind her. Little Crow kept the train moving along the south bank of the Minnesota River for another five miles until they reached the mouth of Rush Brook, a deep, picturesque creek across which lay the Hazelwood mission station, a gathering of tepees, frame houses, and farm fields on the prairie where for eight years the Presbyterian minister Stephen R. Riggs had overseen a church and school for Christian Dakotas. The Hazelwood Republic, normally home to a few hundred members of the Upper Dakota bands, was now crowded with many times that number, most of whom were fearful of Little Crow’s approach and unwilling to join the war effort.

If the East held white people and white machines and white weapons, ever greater in number as one traveled toward the Atlantic Ocean, the West contained its own impediments to Little Crow’s plans. The Wahpeton and Sisseton Dakota, the Upper Agency bands, were kin to the Mdewakantons and Wahpekutes by blood, marriage, language, and custom, but they were also a different people with different rhythms of living who spent much of their year out on the plains of the Dakota Territory, trading and hunting with the Yanktons and Yanktonais. In this complex world of bands and villages, understood by few white settlers or city dwellers, no overall Dakota consensus could exist. In fact, to many Dakotas living along the upper reaches of the Minnesota River, near where the state ended and the Dakota Territory began, Little Crow was no hero but a troublemaker determined to rain down misery on all of them.

That night, August 28, the Mdewakanton tiyotipi sent several hundred men across Rush Brook to the camp of the Sissetons and Wahpetons for the purpose of bringing them into the fold. The men surrounded the camp, riding in swift circles as they shouted, sang, fired their guns, and issued threats that the tepees of the Upper Agency Dakota would be destroyed if they did not join their Lower Agency counterparts. Dismounting, the Mdewakantons sat down to a meal and an animated conversation with their new adversaries, who called them trespassers on their land and promised to “take up arms against them and die on the spot rather than move into the camp of the insane followers of Little Crow.” When the food was finished and the night growing long, the Mdewakantons got back on their horses, fired their guns into the air, promised to be back in the morning, and left. When they returned at daybreak, they found that the Upper Dakota had been busy during the night forming their own tiyotipi, a rival soldiers’ lodge signified by a newly raised tepee, oversized and colorfully decorated, that now dominated the center of the opposing camp. The Mdewakanton warriors, who had expected no organized resistance and had been given no orders to fight a battle against other Dakotas, turned and rode away.

That afternoon, Little Crow watched as one hundred or more Sissetons and Wahpetons turned the tables, riding in and out of his own camp on horseback, their faces and bodies painted, carrying guns, bows and arrows, and knives, all the while making an ear-shattering noise of their own. The Upper Dakota were angry about the display of the night before and feared that Little Crow intended to make prisoners of any full-blooded Dakotas who opposed him. Little Crow and the men of the wartime tiyotipi stepped forward to meet their new adversaries and a great council began, one that would go on for several days and feature many different speakers making speeches as stirring as any the war would produce. All of the orators argued in favor of very different means to the same end. Everyone wanted a conclusion to the war, but only if it could be managed on their own terms.

The first to speak was Paul Mazakutemani, a Christian Wahpeton and an organizer of the Hazelwood Republic, who stepped up to make the Upper Dakota’s demands: they wanted their kin returned to them, mixed-bloods and full-bloods, captives and warriors, and they wanted whatever plundered property belonged to them returned as well. Considered the speaker of the Upper Agency bands, Mazakutemani was every bit Little Crow’s equal at holding the attention of a crowd. In his opening speech, one of great length, he went well beyond the issue of protections for his kin and decried the prosecution of the war itself.

I want to speak now to you of what is in my own heart. Give me all these white captives. I will deliver them up to their friends. You Dakotas are numerous—you can afford to give these captives to me, and I will go with them to the white people. Then, if you want to fight, when you see the white soldiers coming to fight, fight with them, but don’t fight with women and children. Or stop fighting. The Americans are a great people. They have much lead, powder, guns, and provisions. Stop fighting, and now gather up all the captives and give them to me. No one who fights with the white people ever becomes rich, or remains two days in one place, but is always fleeing and starving.

These words were not lost on Sarah, whether she was close enough to hear them or not. Like the other captives, she knew that a “peace party” was forming, though no one yet called it by that name. She knew that many of the Dakota traveling with them had no love for what many called Little Crow’s War. For those whites in Minnesota who imagined a single many-headed Dakota enemy roaming everywhere over the prairie with bloodshed in its heart—and who would continue to hold on to this vision in the days, months, and years to come—the sights and sounds of tribal wrangling would have been incomprehensible. The Dakotas opposed to the war were a heterogeneous group: old and young, men and women, Christians and non-Christians, farmers and buffalo hunters. Here above the Upper Agency, where the plains of the Dakota Territory beckoned, unusual alliances were forming as the opposition to Little Crow’s aims, voiced so boldly and openly by Paul Mazakutemani, also spread from lodge to lodge in whispers.

Little Crow gauged the situation and decided that mixed-blood relations of the Sissetons and Wahpetons should be freed to join their relatives, and also that plundered property should be returned. But the white captives, he said, must remain with him. Little Crow’s spokesman during the opening councils was Wakiyantoecheye, or Thunder That Paints Itself Blue, son-in-law to the powerful village leader Wabasha and a forceful speaker in his own right, who argued that the captives “should not be released, that the hostile Indians had brought trouble and suffering upon themselves, and that captives would have to stay with them and participate in their troubles and deprivations.” Little Crow also abandoned his efforts to combine the two camps, now referred to as “hostile” and “friendly” to whites, into one; he recognized the obvious, that should he attempt to merge them by force, the result would be disastrous.

When Little Crow finally addressed the crowd, well into the councils, he flatly rejected any notion of surrender or parley with the whites. According to one mixed-blood observer, Little Crow finished his oration by saying that he was “the leader of those who made war on the whites; that as long as he was alive no white man should touch him; that if he should ever be taken alive, he would be made a show of before the whites; and that, if he was ever touched by a white man, it would be after he was dead.”

Every day they now continued to talk in council would be a day that white forces drew nearer. Little Crow was also aware that the rival camp was setting up as a haven for hostages who might try to escape, and he was suspicious that Paul Mazakutemani and other Sisseton and Wahpeton leaders might already be sending private messages to white authorities. The time for negotiation was over, and at the end of one particularly heated debate, the young warriors of the Mdewakanton tiyotipi simply walked away, singing as they went.

The song was an old one, sung by Dakota warriors heading into battle against the Ojibwe, now used as the final rebuke to all of the Dakota arguing for an end to their campaign of freedom and vengeance. “Over the earth I come,” they sang.

Over the earth I come;

Over the earth I come;

A soldier I come;

Over the earth I am a ghost.

Little Crow’s troubles were multiplying. He now knew that he could count on no other Indians in Minnesota—not the Ojibwe, not the Ho-Chunks, not the Sissetons and Wahpetons—to join in all-out war against the whites. A growing peace party now occupied the camp not two miles away. The Dakota’s ammunition was almost gone and they had no easy way to replenish it. He knew beyond any doubt that white soldiers were finally coming after him in great numbers, and more than all of this, he knew the man who rode at the head of those soldiers. As they moved into the second phase of their war, the Dakota would not be facing a white leader who was a stranger to their people and their history, or to Little Crow himself. In fact, very few generals facing off on the faraway fields of the Civil War knew each other any better than Little Crow knew Colonel Henry Hastings Sibley.

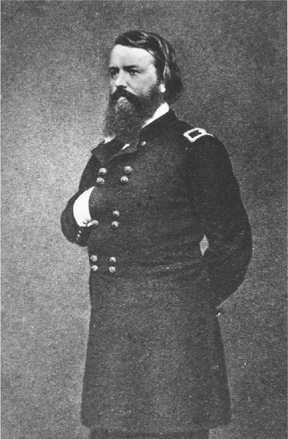

Born in Detroit in 1811, Sibley had trained for the law with an eye toward emulating the career of his father, a prominent judge, before he found his own calling in the fur trade, rising from clerk to chief purchasing agent of the American Fur Company. Once the most famous commercial enterprise west of the Alleghenies, the American Fur Company, brainchild of John Jacob Astor, had established outposts in the Northwest Territory as early as 1820, taking advantage of a near-monopoly and the worldwide mania for beaver, fox, and buffalo pelts to make Astor the country’s richest man. But even as Sibley arrived in 1834 to run the Upper Mississippi district of the Western Outfit, an American Fur Company subsidiary, the fur boom was beginning to fade, a victim of aggressive competition from the Hudson Bay Company, the rapid depletion of game throughout the Northwest, and sky-high demand for plantation-produced cotton and silk.

For fourteen years, between the day he arrived and the day the Minnesota Territory was created in 1849, Sibley experienced firsthand as many aspects of Dakota life as was possible for a white man. Success in the fur trade depended on tying bonds to the Indian world via gift exchanges, displays of physical skill, earnest participation in council, and common kinship, and Sibley qualified in all respects. He befriended Little Crow’s father and became a regular companion to the Mdewakantons, accompanying those warriors closer to his own age on hunting expeditions and living in the band’s villages for months at a time, receiving furs in exchange for goods, weapons, and gold. In 1841, at thirty, he fathered a girl with a young Mdewakanton woman named Red Blanket Woman. Though the mother would die of unknown causes a few years later and the child, Helen, would be placed with a white foster family, in Dakota eyes Sibley had bound himself to them with the tightest possible knot.

On one of his early hunting trips to the West, Sibley had witnessed Taoyateduta, one year his junior, perform an astonishing physical feat. As Sibley and other traders pursued a great herd of elk over the plains for five days, covering 125 miles on horseback, the future Little Crow ran beside them all the while on bare feet without asking for a halt. Intoxicated by his sojourns with the Indians, Sibley published a series of colorful frontier dispatches in The Spirit of the Times, a New York newsweekly for armchair sportsmen, writing under the nom de plume “Hal, a Dacotah.” In 1845, when Taoyateduta’s father, the third Little Crow, suffered an accidental gunshot wound, Sibley had dashed to Kaposia with a doctor from Fort Snelling, where he learned that the old man would likely die soon. That night, the trader watched as the dying chief reluctantly passed the mantle of leadership to his eldest son, one of the two half brothers who would claim the title of village leaders before Little Crow arrived. Sibley knew the rest of the story, too: how Taoyateduta stood unarmed and defiant before his siblings, who shot and crippled the younger Little Crow. He knew that the half brothers had left in disgrace, and he knew that they had soon been found dead. And he knew from the start that the new Little Crow would be intelligent, formidable, and unpredictable.

Four years later, in 1849, Sibley had become the Minnesota Territory’s first delegate to Congress, where he worked closely with Governor Ramsey to “extinguish the title of Indian lands” as they built the case for statehood. His entry into politics drew a stark dividing line in his life and fundamentally changed his relationship with the Dakota. In the negotiations leading up to the treaty of 1851, Sibley emerged as the leading voice behind the traders’ interests, conferring with Little Crow and other Dakota leaders to ensure that the treaty established the system of credit and debt that would escalate year by year and come to play such a major role in the outbreak in 1862.

This was accomplished partly through a “trader’s paper,” a second document setting aside hundreds of thousands of dollars in annuity monies for traders that many Dakota signatories were led to assume was merely a second copy of the treaty itself. The paper was a cheat, but one that some Dakota leaders with close ties to traders may have tolerated at first, failing to foresee the degree to which it would put so many of their kinsmen in arrears each year. Along the way Sibley received substantial payments out of the annuity funds, rewards running into the tens of thousands of dollars, helping to make him rich and propel him forward as a leading man in the territory. Running as a Democrat, he was elected as Minnesota’s first governor in 1858; he chose not to run again in 1860 so that he might play a larger role on the national political stage.

Such was Sibley’s story up to August 19, 1862, when a messenger from Alexander Ramsey, his old friend and political rival, rode up to the door of his three-story house, the first stone structure in the town of Mendota, across from Fort Snelling at the confluence of the Mississippi and Minnesota rivers. The governor considered no one else for the job, assigning Sibley the rank of colonel on the spot and asking him to take command of the hastily assembled group of impromptu militia and Union army recruits who were to head toward Fort Ridgely and quell the Indians.

Sibley took the commission and immediately stewed through a series of delays that began with the delivery of thousands of weapons mismatched with the available ammunition. Leaving Saint Peter on August 25, he had reached Fort Ridgely, only forty miles away, on August 29, eleven days after the war began and four after Little Crow began moving away westward after the attempt to take New Ulm was abandoned. There at the fort Sibley’s offensive stalled again as he attended to refugees already present and those coming in, all the while working to determine Little Crow’s location and waiting on supplies. Nearly half his cavalry simply went home rather than sit around any longer, and newspaper editors, settlers, and soldiers all began to question his caution and pace as attacks on the settlements continued and the fate of the captives remained unresolved.

Little Crow knew about all of these developments, thanks to the runners and riders constantly converging on his lodgings. The decision to turn and fight after the councils with Paul Mazakutemani and the other Upper Dakota may have been his or it may have been made by the wartime tiyotipi, but in either case he hoped that striking a quick blow would fracture Minnesota’s confidence in Sibley and give the Dakota more time. Two major detachments of warriors now set out to the east from Rush Brook. One, led by one of Little Crow’s head warriors and numbering three hundred men, headed down the government road along the Minnesota River, bringing along empty wagons in order to retrieve such supplies and weapons as they could from Little Crow’s old village and to loot New Ulm, should they find it still abandoned. The other party, made up of Little Crow and more than a hundred warriors, moved back toward the Big Woods to ascertain the possibilities in that direction.

A day or two out, a telling exchange took place between Little Crow and his men, one that laid bare abrasions within his own circle of followers. As their party camped on the prairie, Little Crow drafted letters to Colonel Sibley and Governor Ramsey in which he boasted of the panic gripping the state and suggested a cease-fire. He would return the prisoners in exchange for a new treaty, the restoration of annuities, and a lump settlement in gold. The letters were never sent; when read aloud, they were shouted down by his warriors. This response did not bother Little Crow overmuch; such was the way of a Dakota council, and besides, he was always dipping his hand in many wells to see what he could bring up. More distressingly, though, seventy-five of Little Crow’s companions rejected his plan to make a series of movements to threaten the capital and left the camp to loot and plunder at their pleasure.

As they approached the town of Hutchinson, Little Crow’s party, now reduced to fewer than fifty men, came upon a company of recruits raised for the Tenth Minnesota Regiment. The skirmish cost the whites six men and the Dakota one, while Little Crow suffered only a torn coat from an enemy bullet. The Dakota took a few horses and supply-laden wagons, but they had also signaled their meager firepower and numbers to the enemy. When Little Crow followed the soldiers into Hutchinson, he found no people in sight and an impressive stockade in the center of town. Something about this fortification seems to have taken the wind out of Little Crow; surely this meant that other towns in the vicinity had done the same and would no longer be so easily frightened. After a quick attempt to set fire to the stockade, Little Crow and most of his men abandoned their foray into the settlements and turned back in the direction of their camp along the Minnesota River, loading up their wagons with loot from the forsaken farms and buildings along the way and burning empty houses as they went.

Little Crow took no pleasure in any of this activity, disgusted that such minor mischief seemed to be all that was left to him. On or about September 6, he and his men arrived back at Rush Brook to find that Paul Mazakutemani and the members of the peace party were still camped across the creek, well aware that they had had four days to hatch their own plans. Little Crow’s mood soon lifted, though, when a unexpected dispatch arrived to announce that Fort Abercrombie, the federal enclave along the Red River of the North, had been repeatedly attacked and was now under siege by a splinter group of Upper Dakota warriors allied with a few Yanktonais and Cut Heads from the Dakota Territory. Ten Indians and two soldiers had been killed so far and the garrison stood firm; still, the action represented another potential front in the war, one that might be able to draw away some of Sibley’s men and, most important, encourage other western tribes to join in.

And this news was nothing compared to the information Little Crow received when the other Mdewakanton foray returned to camp, shouting excitedly and boasting of a great triumph. Moving through the settlements on the north side of the river after crossing at the Lower Agency, the warriors had come across a large contingent of Sibley’s soldiers camped adjacent to a small hollow on the prairie called Birch Coulee. Captain Hiram P. Grant, along with the current and previous Indian agents, Thomas Galbraith and Joseph R. Brown, had been leading a large burial party into the fields and towns where much of the first week’s killing had occurred, on the assumption that the Dakota had moved north for good. Easily surrounded and especially vulnerable from the wide depression that gave the site its name, the whites had been helpless when Dakotas had risen out of the grass on all sides in the early dawn and begun to fire. Twenty-four whites had been killed or were left dying, four dozen more were badly wounded, and hundreds of others were trapped in their ill-advised camp without food or water and surrounded by the Dakota, who backed off to a safe distance and kept the roads under watch.

The sound of so much gunfire carried clearly over the featureless grass, and that evening 240 men with artillery had set out from Fort Ridgely to see what was happening. Sibley followed with several companies, and on the morning of September 3 he arrived, unmolested by unseen Dakota, to find dead horses, dying men, and famished survivors. After ordering burials and a return to Fort Ridgely en masse, he planted a stake at the center of the field and affixed to it a cigar box with a note inside, a note he knew Dakota scouts would retrieve before heading back up the river valley: “If Little Crow has any proposition to make to me, let him send a half-breed to me, and he shall be protected in and out of camp.”

Now Little Crow was back in his Rush Brook camp with Sibley’s message in hand. He knew that his reply would stand as the first official exchange between war leaders and enter the record as an official statement of Dakota intent, and for this reason many interpreters were employed both in reading Sibley’s note and in crafting Little Crow’s answer. After council was complete and the answer prepared, two mixed-blood couriers were chosen and given a small mule and a single buggy to take south under a flag of truce. Sibley hadn’t asked why the Dakota were fighting, but that was what Little Crow explained. His response referred to the governor, the Indian agent, and the insults of the traders who had been among the first to die in the attack on the Lower Agency.

We made a treaty with the government and beg for what we do get and can’t get that till our children are dying with hunger. It is the traders who commenced it. Mr. A. J. Myrick told the Indians that they would eat grass or dirt. Then Mr. Forbes told the Lower Sioux that they were not men. Then Roberts was working with his friends to defraud us out of our moneys. If the young braves have pushed the white men, I have done this myself. So I want you to let Governor Ramsey know this. I have a great many prisoners, women and children. It ain’t all our fault.

Little Crow did not wait for Sibley’s answer, but moved his camp away from the Rush Brook site along the river bluff, toward the village of a Sisseton chief, Red Iron, ten miles distant. Paul Mazakutemani and the others in the friendly camp followed, wary of Sibley’s intentions should he come upon them and assume them to be hostile. Each removal brought the Dakota closer to the Red River of the North, which marked the state’s western edge and presented a boundary that was topographical, political, and psychological. Little Crow knew that his influence was weakening, that Dakota loyalties were many-faceted, and that he needed to keep a safe distance between himself and the white forces. He may even have known that some of his own Mdewakanton people, men who had opposed the war from the start, had now taken prominent places in the peace party. Indeed, some of those men were beginning to write their own private messages to Sibley protesting their innocence, blaming Little Crow for the war, and offering to deliver up as many prisoners as they could once Sibley finally reached their camp.

As Little Crow approached Red Iron’s village, a force of mounted and armed Sissetons with their chief in the lead rode down the reservation road at him, so hard and fast that the van of Little Crow’s men was forced to wheel and scatter. The Sissetons did not attack; their ride was a show of defiance and independence, a warning to Little Crow and all of the Lower Dakota not to presume they could simply ride in without permission. After Red Iron and his men retreated, Little Crow gathered together his train, stopped them for the night, and sent Little Six, the young Dakota leader whose men had provided the original push for war, forward with a formal request that Red Iron join with them against the whites.

A great gathering of Dakota now formed near Red Iron’s village. The factions included Little Crow’s camp, home to the wartime tiyotipi and the white captives; the friendly camp and the leaders of the peace party; Red Iron and his warriors; and other leaders who now arrived from nearby villages, including Standing Buffalo, the most powerful and influential chief among the Upper Dakota. When the councils began, each of these groups stood at a distance apart from the others, sending forth their spokesmen and receiving reports and communications from the councils and from runners and riders throughout the region.

The talks were intense and urgent, focused on the fate of the captives, the possibility of surrender, and the likelihood that white leaders could be trusted to act in good faith. Paul Mazakutemani repeated his dismay that war had been declared without the consensus of all the Dakota bands, and then he demanded the release of the prisoners: “I want to know from you Lower Indians whether you were asleep or crazy. In fighting the whites, you are fighting the thunder and lightning. You will all be killed off. You might as well try to bail out the waters of the Mississippi as to whip them.” When Mazakutemani finished, some of the Mdewakantons whooped and threatened to kill him for what they viewed as his traitorous stand, but such a threat couldn’t be carried out without starting a donnybrook that would destroy all the Dakota, and the council continued.

As was his way, Little Crow waited out the various speakers. One observer recorded Little Crow’s firm opposition to the demand that he open talks with Sibley. “I wish no more war,” the chief said. “But if we give up all the prisoners, we must run away, or we shall all be shot. I do not justify the killing of women and children. I gave orders to kill only traders and government agents, who have cheated the Indians. But now we wish to settle the question, whether we will fight or run. We must do one or the other.” Peacemaking was not a choice. If the Dakota were taken by whites, said Little Crow, they would be hanged, all of them. Die he might, but only in the fashion of a warrior.

I tell you we must fight and perish together. A man is a fool and a coward who thinks otherwise, and who will desert his nation at such a time. Disgrace not yourselves by a surrender to those who will hang you up like dogs, but die, if die you must, with arms in your hands, like warriors and braves of the Dakota.

Standing Buffalo and Red Iron, acting from positions of advantage, listened respectfully but continued to stand aloof from the Lower Dakota. By now Little Crow knew that Sibley was finally moving, coming upriver at the head of thousands of soldiers and hoping to wipe out the Dakota warriors without harming any of their captives. At some point during the councils, a mixed-blood courier entered the camp with Sibley’s terse response to Little Crow’s latest message. The note contained nothing that Little Crow had not expected. “You have murdered many of our people without any sufficient cause,” wrote Sibley. “Return me the prisoners under a flag of truce, and I will talk to you then like a man.” Sibley also penned what he called an “open letter” to “those of the Half-Breeds and Sioux Indians who have not been Concerned in the Murders and Outrages upon the White Settlers.”

I have not come into this upper country to injure any innocent person, but to punish those who have committed the cruel murders upon innocent men, women, and children. If, therefore, you wish to withdraw from these guilty people you must, when you see my troops approaching, take up a separate position and hoist a flag of truce and send a small party to me when I hoist a flag of truce in answer, and I will then take you under my protection.

Little Crow knew that he had become a target, and not just of white soldiers. He was well aware that someone within one of the rival Dakota camps might even now be arranging for his capture, and capture—not death in battle, which would bring only honor—was what he dreaded most. His choices, then, were to run to the West or to turn and fight. Running might give him time, but it might also allow Sibley’s soldiers to keep moving on his heels while the season would still allow it. A chill was creeping into the night air, now that August was past, and Little Crow knew that no large armed force would cross onto the plains once winter began. At the very least, he needed to give Sibley’s army one more reason to pause. Soon Little Crow might have to flee. But now he would fight.

John Nicolay’s return trip to the Ojibwe agency at Crow Wing, ten miles above Fort Ripley, was colored from its start, on August 26, by a piece of unsettling news. Lucius Walker, the Ojibwe agent who had fled Saint Cloud in a panic one week earlier, had been found dead, his pistol next to him and a gaping gunshot wound in his side. Everywhere Walker had stopped along the Mississippi River on his dash south, it seemed, he had described an imaginary force of 250 Ojibwe warriors hard on his heels and bent on his scalp. The possibility that Walker’s death, though an apparent suicide, might indeed have been the work of a small party of Ojibwe was cause for alarm, but at least now Walker’s reputation among the Ojibwe as a corrupt, incompetent Indian agent would no longer hinder their negotiations.

All entreaty in the Ojibwe villages near Fort Ripley ran through one man, Bagone-glizhig, or Hole in the Day, whose life story so resembled Little Crow’s that the two sometimes seemed different sides of the same coin. Both were scions in a line of consequential chiefs whose fathers had received decorations from the British during the War of 1812. Both had dabbled in Christianity without abandoning ancient systems of belief. Both had traveled to Washington to meet with presidents and other white leaders, and both had been instrumental in negotiating land-cession treaties, playing roles that had left them in ambiguous positions within their own tribes. Each had taken part in regular raids against the other’s tribe, and rode with raiding and hunting parties on disputed grounds. But after rising to their leadership positions each had seen the value of regular correspondence with the other, and over the past few years they had spoken together often in Saint Paul as they found themselves more and more disillusioned with the government’s broken and altered promises.

Before leaving Saint Paul to go up the Mississippi River for the second time, Nicolay wrote John Hay to say that “the muss with Hole-in-the-Day is a complicated affair, involving official frauds on the one hand and Indian depredations on the other,” and adding, “I see that the rebels are almost in Washington. How does your head feel? It looks very much as if it were about as safe as my scalp.” The “official frauds” involved a series of brazen embezzlements by Walker, late annuity payments, spoiled or unusable treaty goods, and the increasing coercion of mixed-blood Ojibwes into the Union army. On August 17, the day before the Dakota attack on the Lower Agency, Hole in the Day had dispatched runners to Ojibwe villages at Leech Lake, Otter Tail Lake, and Rabbit Lake, telling them, according to Nicolay’s intelligence, to “kill all the whites, rob their stores and dwellings, and join him at once with their warriors at Gull Lake, some thirty miles from the Government Agency.”

The order to kill whites, if indeed such an order existed, was ignored, but the few settlers in those locations—perhaps one hundred in total—found themselves plundered of their provisions and stocks, their cattle and other livestock destroyed. Some white men were taken to be held hostage at the Gull Lake negotiations. On the same day as the Dakota attack on the Lower Agency, as the number of Ojibwe warriors at the Crow Wing village grew into the hundreds, Walker had tried and failed to arrest Hole in the Day. That was when the agent had fled and eventually found Nicolay and Dole in Saint Cloud, where he delivered his prediction of statewide war and told stories of hundreds of Ojibwe warriors coming to kill him. Now Walker was dead, an interim agent in his place, and Hole in the Day was ready to treat with white officials.

When Nicolay’s party reached Fort Ripley on August 29, they found that Hole in the Day had taken umbrage at the company of infantry in their wake and retreated to join the mass of Ojibwe warriors thirty miles to the north. His instructions to Commissioner Dole were to wait, and so they waited, day after day. During this interim, another letter from John Hay found Nicolay. “Where is your scalp?” it began. “If in God’s good Providence your long locks adorn the lodge of an aboriginal warrior and the festive tomtom is made of your stretched hide, I will not grudge the time thus spent, for auld lang syne. In fancy’s eye I often behold you the centre and ornament of a wildwood circle delighting the untutored children of the forest with Tuscan melodies, while from enraptured maidens comes the seductive invitation.”

After two weeks of exasperated waiting, Dole agreed to Hole in the Day’s demand that they meet not at the fort, nor at the agency, but near the Indian village at Crow Wing. At noon on September 10, 1862, almost two weeks after Nicolay had arrived, the Ojibwe approached a small dell that Hole in the Day had designated as the council ground. “They came on in irregular, straggling groups, chiefs and braves promiscuously intermingled, not following the road but the bank and beach of the river,” Nicolay wrote.

It was a picturesque group. The bold, high angle of bank and point of yellow sand-beach jutting out into the bend of the stream, and the shining and rippled expanse of its waters; the swarthy figures of the savages, in their various and carelessly-graceful attitudes and costumes, clearly and sharply outlined against the dark-green background of pine foliage on the opposite side of the river, with occasional red and white blankets, making bright spots of color that lighted up the whole scene.

Dole opened the discussions by demanding the release of all white captives, following which the infantry captain assigned to guard the commissioner threatened that the Ojibwe would be “blown to hell in five minutes” should they fail to comply. Hole in the Day did not respond, other than to give a signal that brought forth one hundred additional warriors, stepping into view behind the white officials and leaving them outnumbered, subject to crossfire, and cut off from escape. Dole stepped forward to complain about the display of force but soon switched to a more conciliatory approach. As one white trader on the scene wrote, he “gave them a short nice speech telling them how glad he was to see them but I would bet he was wishing himself all the time that [he] was in his good arm chair in his office in Washington.” Hole in the Day responded with disgust, telling Dole, “If you are the smartest man the Great Father has got, I pity our Great Father. You have been talking to me as if I was a child. I am not a little child.”

Nicolay, who feared that “a deadly and desperate melee” was in the making, described the council that followed as “merely an hour’s preliminary, pointless talk, a wordy and circumlocutory concealment of objects which would have done credit to the most bestarred and bespangled diplomats.” The Ojibwe moved off, and the commissioner and his soldiers did likewise. After one more day of sluggish talks Dole decided to go back to Saint Paul and hand the job over to Governor Ramsey. Hole in the Day had no intention of joining an all-out war against the whites. Rather, two weeks of posturing had gotten the chief exactly what he did want: confirmation of his own influence and a promise that the state would attend to the grievances of the Ojibwe in order to prevent the opening of another front in their sudden war. Both sides, white and Indian, could claim success, and both sides did.

Riding the steamboat on his return to Saint Paul, Nicolay penned a final note to John Hay. “My scalp is yet safe,” he wrote, “but day before yesterday it was not worth as much as it is tonight.” Nicolay departed Minnesota for Washington on September 13, bearing a report for the president and a file of notes ready to turn into one of the first articles about the Dakota War to be published in a prominent eastern magazine.

The military engagement that Lincoln had so anxiously awaited during August had turned into the Second Battle of Bull Run, probably the greatest disaster of the war for the Union army. Unsupported by McClellan, General John Pope and his forces spent two weeks chasing shadows around Northern Virginia before the combined forces of Stonewall Jackson and James Longstreet sent his men scrambling back across the Potomac River, leaving the Confederates in control of all of Virginia and scuttling Lincoln’s chance to announce his plans for emancipation. On September 2, the president told his cabinet that he “felt almost ready to hang himself,” and while he was known to make melancholic jokes, the present circumstances leached away most of the humor. McClellan had hung Pope out to dry and deserved to be removed from command, but Lincoln had no suitable replacement in line and refused to cut “Little Mac” loose, much to the dismay of his cabinet.

It was a time of increasing division inside the White House, yet everyone could agree that the disposal of John Pope in the wake of Second Bull Run had to be handled with a great deal of sensitivity. To dismiss Pope from the service would make the administration appear incompetent for promoting him in the first place, while to leave him in charge of any forces in the East would dispirit the soldiers. There was also the matter of Pope’s personal connection to the president. Born in Louisville and raised in Kaskaskia, Illinois, he was the son of Nathaniel Pope, Lincoln’s favorite federal judge and the man who had admitted him to practice in Illinois’s circuit court. Like his father, John was loquacious, ambitious, and prone to exaggeration, equally capable of inspiring loyalty or inviting scorn. Both were gruff, doughty men, well-read and well-educated and prone to abuse their superior knowledge in their treatment of subordinates or legal petitioners. When John graduated West Point in 1842, his final standing in the class, a respectable seventeenth out of fifty-six, nonetheless left his father disappointed, putting a chip on the son’s shoulder that took many years to fall off.

The younger Pope had been one of four men selected to accompany Mary Todd Lincoln on her pre-inaugural journey from the Midwest to Washington, D.C. Pressed into service at the start of the Civil War, Pope won a string of minor victories along the Mississippi River before using a series of newspaper interviews and letters to Lincoln to paint himself as a precocious military mind, something he decidedly wasn’t. But with military talent so short in the early incarnation of the Union army and George McClellan unwilling to take the offensive, Pope had been called east to head the Army of Virginia, 75,000 men with two jobs to do: stop Robert E. Lee and drive him back to Richmond.

Pope’s lasting infamy among Union forces was less a result of his defeat at Bull Run—plenty of Union generals, including McClellan, had suffered defeat—and more a by-product of his bloated, pompous style of leadership. Arriving in Virginia in early August, he had said perhaps the most ill-advised hello in military history. “Let us understand each other,” Pope wrote to his new charges. “I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.” Not satisfied with insulting his men, he then insulted the strategic acumen of their beloved former commander.

I desire you to dismiss from your minds certain phrases, which I am sorry to find so much in vogue amongst you. I hear constantly of “taking strong positions and holding them,” of “lines of retreat,” and of “bases of supplies.” Let us discard such ideas. The strongest position a soldier should desire to occupy is one from which he can most easily advance against the enemy. Let us study the probable lines of retreat of our opponents, and leave our own to take care of themselves. Let us look before us, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.

Pope’s bombast earned him lasting scorn after he found himself out of his depth on the fields of Northern Virginia. He had also made Lincoln’s job more difficult by ensuring that he could not be moved to another position in the Union’s eastern armies.

On September 4, Pope had arrived at the White House to lay seven pages of complaints about his abandonment by McClellan in front of Lincoln, who agreed with many of Pope’s points but who could also see that he had a broken, bitter man on his hands. In the end, the Dakota War provided Lincoln with a convenient solution. Two troublesome situations could now be taken care of with one order. If the governors of the states and territories in the Northwest wanted a new military department to deal harshly with the “Indian problem,” they would have it. Edwin Stanton’s letter to Pope on September 6 oozed insincere and unctuous regard.

The Indian hostilities that have recently broken forth and are now prevailing in that department require the attention of some military officer of high rank, in whose ability and vigor the Government has confidence, and you have therefore been selected for this important command. You will proceed immediately to your department, establish your headquarters at Saint Paul, Minn, and make yourself acquainted with and report to this department the actual condition of affairs, and take such prompt and vigorous measures as shall quell the hostilities and afford peace, security, and protection to the people against Indian hostilities.

The Dakota War had now been federalized, the new department placed under the command of a general who saw in his assignment only punishment and exile. As John Nicolay headed back east, John Pope was coming west, and he wasn’t happy.