CHAPTER ONE

WHAT TO COLLECT

A true book collector knows whether he is one or not, just as the old saying has it about being in love. A genuine bibliophile is born rather than made. Thus “what to collect” is a question that answers itself. A collector collects what fascinates him. The fascination, in fact, comes before the collection, because most collectors do not begin to collect deliberately. The first step, inevitably, is buying books that reflect one’s interest in a subject or in an author in order to read them. Whether or not they are rare or hard to get is secondary.

My own experience is a case in point. I have a complete collection of Gertrude Stein books; I began to buy them in the first place simply because I wanted to read them. Virtually none were in print. In fact, as recently as 1960, before the intense revival of interest in her work began, only one of her more than sixty titles was available. Anyone who wanted to read Gertrude Stein was forced to seek out copies wherever they could be found—generally in the form of first editions, because only four or five of them had ever existed in any other form. I became deeply involved in the search, and the result is my Stein collection. Nowadays all but two or three of those books are in print again and can be purchased with relative ease. But no matter. In the course of things I had discovered my love of book collecting and the joy that the search can bring.

Once the line between reader and collector has been crossed, there is usually no turning back. There is no cure for the virus. But a distinction should still be made between the collector and the investor. If the acquisition of a rare, long-sought-after book gives you pleasure, a glow, a lift, just because you finally own it, with little or no thought that you may be able to sell it at a profit, then you are undoubtedly a collector and are liable to remain one for the rest of your life. On the other hand, if you buy a book and immediately think, “Aha, I can double the price at X’s,” then you are primarily a dealer or an investor. It’s really as simple and basic as that. (However, as both a collector and a dealer myself, I can testify that the conditions are not mutually exclusive.) In recent years a great many people have begun to collect books as an investment, spurred on, no doubt, by numerous articles in newspapers and magazines written in a breezy, offhand manner and emphasizing the profit motive to the exclusion of almost everything else. Of course, everyone likes to make a profit, and it is normal and human to be pleased when a book you bought a few years ago at publication price or a modest markup starts a price climb in dealers’ catalogs or at auction. But the true collector would sooner die than part with his treasures. Many literally skip meals, wear threadbare clothing, are in arrears on the rent—in short, do almost anything to hold on to their books. Once in a while, a collector gives way to the temptation of an enormous profit. In my experience, which stretches over nearly four decades, in every single case the seller regretted the move almost immediately and forever after.

Most book collecting in this century is done in the field of literature, primarily novels, poetry, and plays. There are, of course, other popular fields such as the sciences, biography, criticism, travel, and so on. The literature of chess is particularly popular. The New York Public Library has one entire room devoted to a collection relating solely to tobacco and smoking (although, ironically, the library’s rules forbid smoking even in that room). The Black Liberation movement of the sixties and seventies gave tremendous impetus to “black” collections, among white as well as black collectors. Your own taste will dictate what you collect. Some people follow trends and fashions, collecting what is most popular at any given time. But to my mind, these people are not true collectors, but faddists—or, even worse, speculators.

Many factors determine what you can collect, not the least of which is the question of cost. Very few collectors starting today can hope to form a collection of Elizabethan literature, much less of Shakespeare. Cost aside, most of the great pieces of Elizabethan literature have by now gravitated into institutions. For example, all known copies of the first edition of Romeo and Juliet are in institutional libraries, so no new Shakespeare collection could ever be complete. Even the great eighteenth-century books, while perhaps slightly more available, are for the most part four-figure items. Important early-nineteenth-century books, particularly those of the Romantic poets such as Byron, Shelley, and Keats, are now fetching prices beyond the reach of the average collector. This has had much to do with the rapid and seemingly endless growth in popularity of modern authors. The term “modern” is bound to be an imprecise one, the meaning of which depends in large measure on one’s own age. To some it means only those authors who came into prominence during the twenties and their successors. However, because of the enormous interest in certain late-nineteenth-century American authors, many dealers and collectors start the modern period with Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson in poetry and Henry James and Stephen Crane in prose. This book uses “modern” in the latter sense.

Another factor, equally as important as price, is availability. If the books are all but unavailable, with only an occasional title surfacing here and there at long intervals, sometimes years apart (as with Shakespearean firsts), there will not be enough activity to keep the collection—and your interest in it—alive. On the other hand, if everything is too easily procurable, if you can expect to gather all the items in a comparatively short time, there will also be little or no excitement. As in almost all other hobbies or sports, the chase is at least half the fun.

The most widespread type of book collecting is undoubtedly the building of author collections, that is, the gathering of all the work of any given author. It can vary from a simple collection of first editions of each book published by the particular author to an intensive, in-depth collection composed of every edition of every book, as well as appearances by the author (with prefaces or the like) in books other than his own, original appearances in magazines and periodicals, recordings and photos of the author, books about him, and so on. There is almost no limit to the boundaries of an in-depth collection.

Apart from author collections, collections are often formed on the basis of preestablished guidelines such as those set by “high spot” or category lists. In 1929, for example, Merle Johnson published the first of his lists of important American books, calling it High Spots in American Literature; a great many collectors set out to get copies of all of the books listed, a vast undertaking, and for many years catalogs regularly noted when a book was a “Merle Johnson high spot.” Prior to that, in 1903, the august and prestigious Grolier Club, whose membership is composed exclusively of book collectors, published a catalog of an exhibit modestly entitled One Hundred Books Famous in English Literature. This list was made up of what could reasonably be called the one hundred finest examples of literature in the language, and even today, decades later, there are still collectors who try to assemble the books on this list. It is not uncommon to see a listing of one or more of these titles in dealers’ catalogs referred to as “one of the Grolier Hundred.”

A few years before his death, Cyril Connolly, an extremely avid collector of first editions as well as an author whose first editions were sought after by fellow collectors, wrote a book entitled The Modern Movement, in which he listed and discussed the one hundred books he believed were influential and crucial in the establishment of twentieth-century literature. He did not restrict his list solely to works in English, but also included important French works. This group immediately became known as the Connolly Hundred. At least one institution, the Humanities Research Library at the University of Texas, set out to gather a complete collection of the books named on this list, many of which it already possessed. With the enormous resources at its command, the library soon assembled the entire group and placed it on exhibit, accompanied by a superb illustrated catalog which has in itself become a collector’s item, since a great many letters and inscriptions were published in it for the first time.

Still another group of books favored by collectors are those that appear on the list of Pulitzer Prize winners, especially in fiction, drama, and poetry. A collection based on this list is far more difficult to complete than might be imagined. While certain famous books, well loved over many decades—Gone with the Wind or The Bridge of San Luis Rey—will appear regularly in catalogs, the Pulitzer Prize, in the inscrutable wisdom of the judges, has gone over and over again to authors who subsequently sank into deserved obscurity, along with their works. As a result, these books can be difficult to find, since most dealers, understandably, are loath to stock a book that may remain on the shelf for many years before a Pulitzer Prize collector happens along.

To my way of thinking, it is far more interesting, and considerably more fun, to determine your own area of endeavor, in spite of the satisfaction to be found in achieving a widely recognized standard. Your goal can be challenging despite not being widely recognized or even popular. It can be as simple—but limitless—as making your own list of high spots, especially for the post-World War II period, where very few such guidelines have as yet been published. Indeed, for collectors who are not drawn to the idea of an in-depth collection, this is an excellent field in which to work, since it is flexible enough to admit any item you like and does not force you to acquire anything in which you are not interested merely for the sake of that tantalizing will-o’-the-wisp “completeness.” A couple of years ago I prepared my own list of what I thought were the fifty most important and influential books published in the field of American literature after the end of World War II, a date that provided a clear-cut line of demarcation between the literature of the two halves of this century. (This list, along with comments on my reasons for including particular books, will be found as Appendix 4).

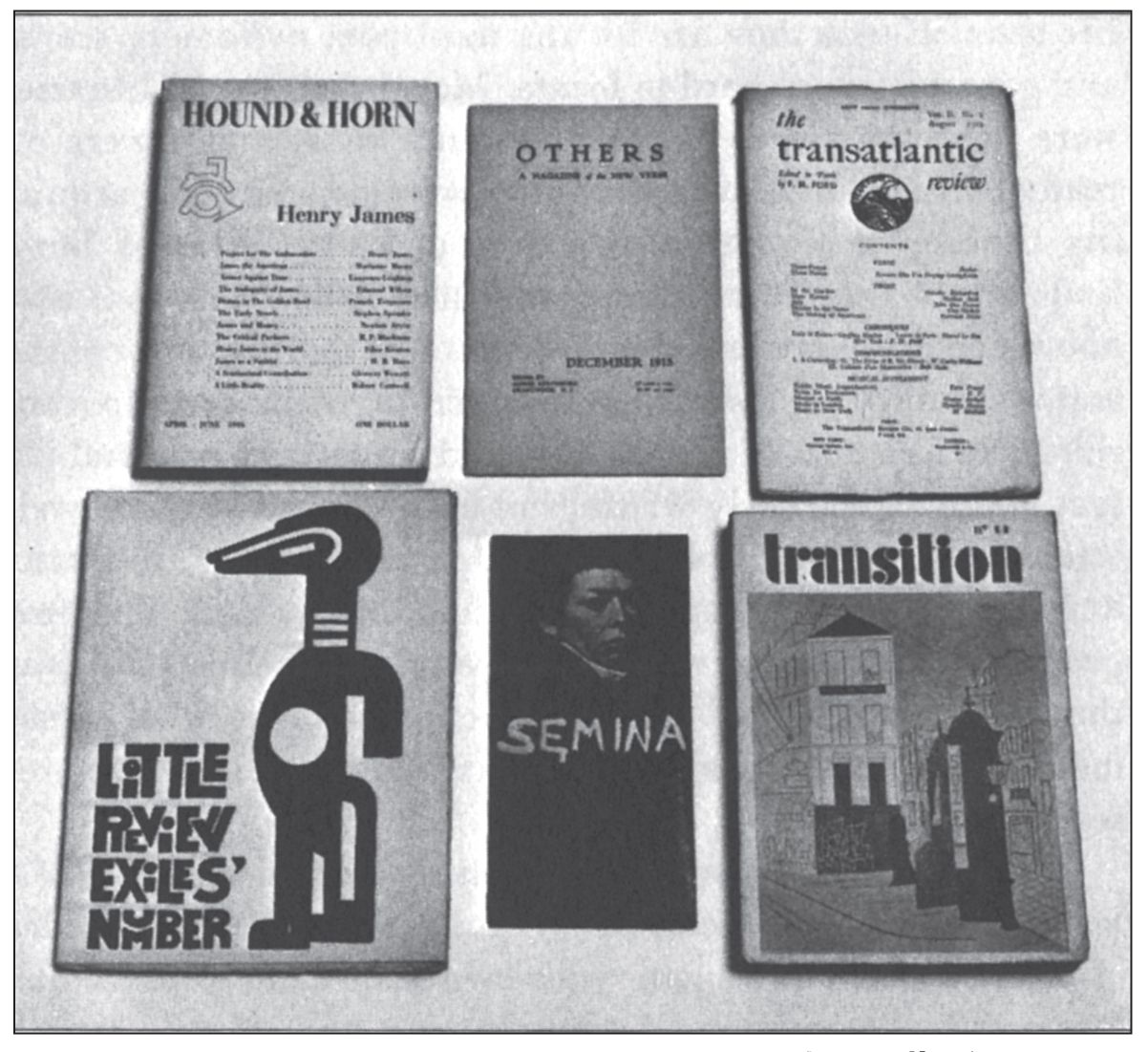

A representative group of little magazines. From the author’s collection.

Another collecting area that is wide and utterly fascinating is little magazines. There are two guidelines: Frederick J. Hoffman, Charles Allen, and Carolyn F. Ulrich’s The Little Magazine: A History and a Bibliography (Princeton, 1946), covering the period up through World War II, and the just published The Little Magazine in America by Elliott Anderson and Mary Kinzie (Pushcart Press, 1978), covering the postwar period up to the present day. This is also a field that is not overcrowded. I do not mean that such a collection is easy to form—on the contrary. Many dealers will not take the trouble to stock magazines and periodicals with the exception of an occasional outstanding issue or a complete run of a classic, such as The Little Review, transition, The Dial, Broom, and Hound and Horn, all of them seminal periodicals of the between-the-wars period. “Little” magazines have been an important part of the literary scene for some time, and there was a burst of feverish activity in this area in the 1950s and ’60s, coinciding with the “beat” movement. It was caused in part by the classic stimulus behind the existence of such magazines—the inability of the young members of the avant-garde to get their work accepted for publication in the more established literary periodicals of the day. But in this period, a new factor entered the picture—the widespread availability of duplicating equipment, particularly the mimeograph, which heretofore had not been generally available to the average citizen. It was now easy to rent or even purchase a relatively inexpensive model, and such a flood of little magazines appeared from these duplicating machines that one writer on the subject, Kirby Congdon, has termed it “the mimeograph revolution.” Naturally, very few of these productions were submitted for copyright; many were not for sale, but merely given away to contributors and their friends. Even those that were placed on sale had a relatively limited circulation and almost always a very short life span. Hence they are for the most part extremely scarce and generally very hard to locate. Most institutional libraries were not even aware of their existence until many were already defunct, and few universities were interested in acquiring them even if they were aware of them. While a large majority of these magazines published little work that rose above the mediocre and were often issued mainly to serve the editor’s vanity, a surprising number of them contain considerable amounts of worthwhile and important material. In fact, many of the early writings of authors who are now well established—for example, Olson, Duncan, Creeley, Kerouac, and Levertov—first appeared in such magazines. The few people or institutions with the foresight to collect them as they were issued now have collections not only of great monetary value, but also of incalculable historical and research importance.

Private presses have long been a favorite area for collecting, in part because of the great beauty of most examples of their output. Here again, your own taste can set the limits. It is possible to spend much money, time, and effort in trying simply to gather a copy of every book produced by one or more of the famous little presses. Equally interesting and challenging would be a collection of one or two examples from each of the great private presses. There have been many famous private presses in the past, from Horace Walpole’s Strawberry Hill and Benjamin Franklin’s Passy presses in the eighteenth century to William Morris’ magnificent Kelmscott Press of the late nineteenth. More attainable for today’s average collector, however, are the products of some of the presses of the twentieth century. These include the Doves Press and the early Nonesuch Press (before it was absorbed commercially), both British, and in the United States, the Mosher Press, operated in Portland, Maine, by Thomas Mosher at the turn of the century.

During the twenties, when most of the young British and American avant-garde writers flocked to Paris, a number of superb little presses sprang up to meet the need for avant-garde publication in the English language. Many of these books have for collectors the double advantage of being not only finely printed, but also rare and important first editions of some of the twentieth-century literary giants. This, of course, doubles the demand for them, since they are wanted both for press book collections and for author collections. Among these presses of special note, the Black Sun Press is perhaps the most famous of all. Operated by Harry and Caresse Crosby, in the brief span of four years it produced a staggering number of books that are now landmarks of twentieth-century literature. These include Hart Crane’s The Bridge, as well as significant titles by Joyce, Pound, Lawrence, MacLeish, Boyle, and others, at a time when most of these names were very little known.

Other presses of this period include the Black Manikin Press of Edward Titus, the Contact Press of Robert McAlmon, Harrison of Paris, Nancy Cunard’s Hours Press, Plain Edition (run by Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein and publishing, naturally, only books by Stein), the Seizin Press, operated by Robert Graves and Laura Riding from a wide variety of locations, and William Bird’s Three Mountains Press. Further details concerning these presses and their products can be had by consulting Hugh Ford’s excellent study of them entitled Published in Paris. While all this was going on in and about Paris, Leonard and Virginia Woolf were operating their now famous Hogarth Press, with Virginia actually setting the type for many of the early titles.

In the United States there have been several fine presses whose work is actively collected. These include the Grabhorn, Cummington, and Banyan presses, and recently the Windhover Press, the Perishable Press (whose operator, Walter Hamady, even makes all his own paper, the size of the edition of any particular book being determined largely by the amount of paper resulting from the specific paper-making operation), and the Gehenna Press, founded by the artist Leonard Baskin.

Another fascinating and challenging scheme for a collection is first books of prominent authors. Most authors’ first books are among their rarest, since very few books by untried, unknown authors are ever issued in large quantities, particularly in the case of poets, where the entire edition may be only a hundred copies or even fewer. The first books of Ezra Pound (A Lume Spento, Venice, 1908) and William Carlos Williams (Poems, Rutherford, 1909) were privately published in editions of only one hundred copies each. But of these very few have survived (in Pound’s case twenty-six copies have been located; in Williams’, approximately a dozen). Allen Ginsberg’s first book (aside from loose mimeographed sheets of an advance portion of Howl), entitled Siesta at Xbalba, consisted of only sixty copies, mimeographed on board a Coast Guard cutter anchored off Icy Cape, Alaska. This little pamphlet is thus one of the rarest titles in twentieth-century poetry. While the three examples cited just now are among the most extreme rarities, a first-book collection can be assembled, although it is in all likelihood the most difficult of all modern book collecting ventures.

One could go on at great length enumerating other fields, but I shall not. Suffice it to name just a few more: books illustrated by famous artists (many such contain original lithographs or etchings); juveniles, or “children’s books,” another field presenting extreme difficulties because of the heavy wear and tear most such books are subjected to by their young readers; books in series, such as the books issued by the Limited Editions Club, or signed limited books in a distinct series, as for example the Woburn Books in England in the 1920s or the distinguished Crown Octavo series issued by the House of Books, Ltd., in New York; and also collections of fine bindings. In this latter field the collection can legitimately extend far back into the sumptuous bindings of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as well as more modern fine bindings.

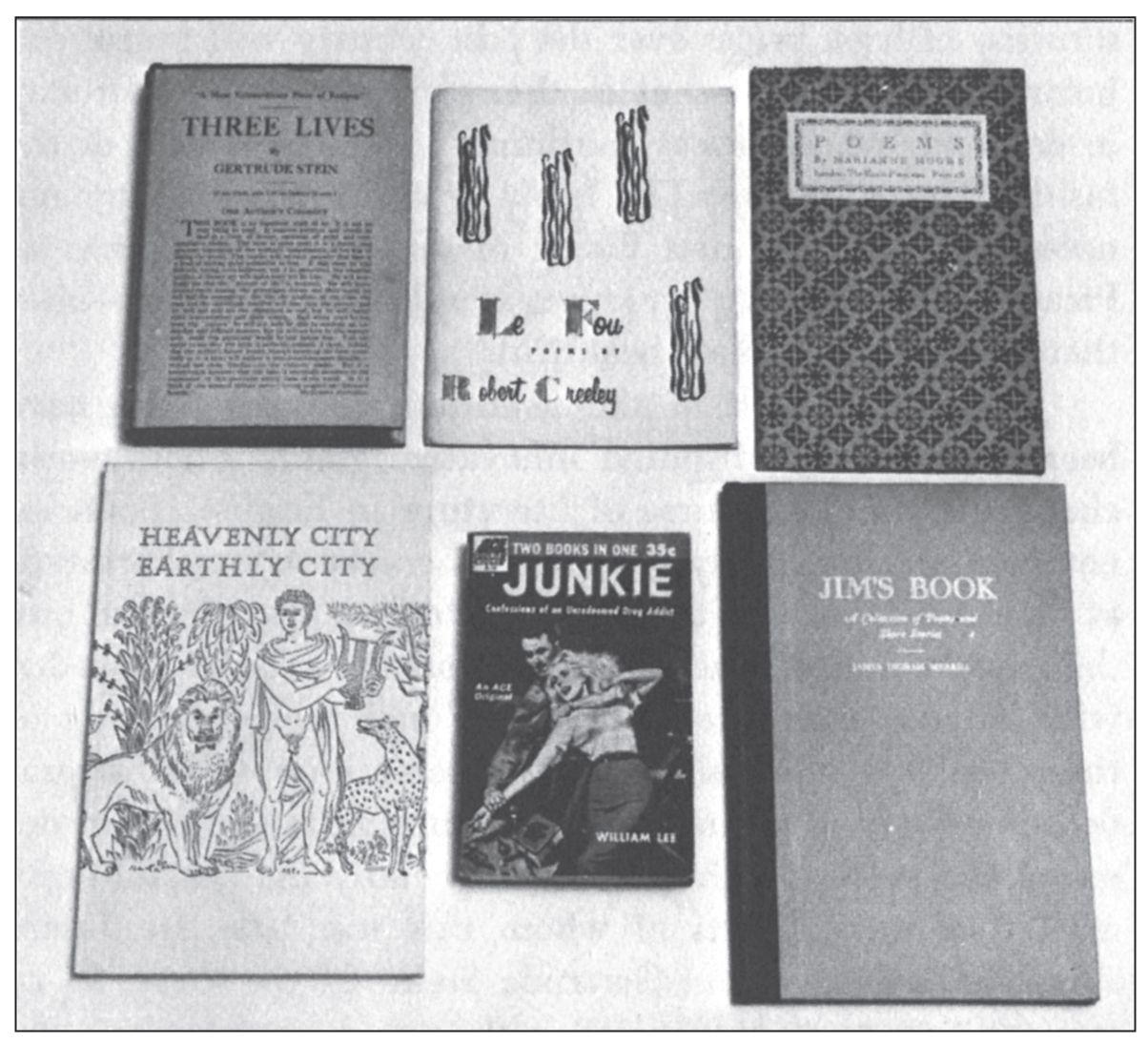

A group of “first books”: THREE LIVES by Gertrude Stein (1909)—this copy has one of only three known surviving dust jackets; LE FOU by Robert Creeley (1952); POEMS by Marianne Moore (1921); HEAVENLY CITY, EARTHLY CITY by Robert Duncan (1947) ; JUNKIE, written by William Burroughs under the pen name William Lee (1953); and JIM’S BOOK by James Merrill (1942). From the author’s collection.

There is one final area of collecting which calls for more extended discussion. I refer to an extremely small group of authors—the innovators or ground breakers, the ones whose work made such an impact that the entire course of English and American literature was altered ever after. A careful scrutiny of book prices over the past century will reveal one incontrovertible fact: that is, theirs are the works that stay in demand, whose prices continually rise, regardless of the fashions in collecting. The books of these writers may not necessarily be the finest flower of an era or an epoch: as Picasso once said, “All creation is ugly the first time—after that any fool can make it beautiful.”

In the first half of the twentieth century there have been three such undisputed innovative giants whose works changed the entire course of literature in English. Such innovators are invariably regarded as crackpots or charlatans at first, sometimes for their entire lifetimes. People who buy their books at the time of publication are usually regarded with amused tolerance at best. Yet once the importance of their work is established—and it sometimes takes several decades—there is virtually no interruption to the rise in demand and prices for their books, especially the crucial early ones. The three giants of whom this was true are James Joyce, Ezra Pound, and Gertrude Stein. Of the three, Joyce was the first to be recognized, although as recently as 1960 the price of the signed, deluxe edition of Ulysses (of which only one hundred copies were issued, not all of which have survived) still had not reached $1,000. But shortly thereafter, a rapid increase in demand for anything by Joyce began, and this chef d’oeuvre became one of the most sought after of all twentieth-century works. Even now there seems to be no slackening of demand. In fact, one collector I know of who has collected Joyce for many years began a few years ago to buy up all possible copies of Ulysses as an investment. His decision seems to have been an extremely astute one. The value of copies of this important book has risen at a far greater—and steadier—pace than that of any stocks, bonds, real estate, gold, or any other form of investment of recent years.

Ezra Pound also came very late to widespread collector popularity, partly because of his long period of incarceration in a mental hospital in Washington pending a possible trial for treason. He had enjoyed a good bit of popularity with collectors of avant-garde work prior to World War II, but for a long while after it most of his books could be had at nominal prices. This period terminated in 1958, when Pound was released as unfit to stand trial. A policy of forgive and forget had already begun to manifest itself, although prices of his books still remained low. Two examples should suffice. The Black Sun Press edition of Imaginary Letters was selling for only $8 a copy in one Park Avenue bookshop in 1962, with multiple copies available. Now, of course, it is much sought after both for Pound collections as well as for Black Sun Press collections. At the time, I bought all they had at that price, including the signed limited copies which were thrown in indiscriminately with the regular unsigned copies. The other example is his first book, discussed previously, A Lume Spento, one of the rarest and most wanted of all twentieth-century books. In 1960 a signed copy that had three manuscript corrections in the poet’s hand, with a Christmas card bearing the first separate appearance of one of the poems laid in, appeared for sale in a catalog issued by the Gotham Book Mart at $185. At the first session of the Goodwin sale in 1976, an inscribed copy of A Lume Spento fetched $16,000, still the highest price on record for a modern American book.

Gertrude Stein was the last of this group to be admitted to sainthood. Scorned and derided by a large part of the literary and academic world during her lifetime and for the two decades after her death in 1946, interest in her work among collectors did not blossom to any significant degree until the early 1970s. It has most certainly still not peaked. As with Pound, as late as the end of the 1960s virtually any title in her large canon of work could be obtained for under $100. (The single exception was A Book Concluding with As a Wife Has a Cow a Love Story, published in 1926 in an edition of only 110 copies. The high price for this book—whose title is almost as long as the entire brief text—can be explained by the presence in it of four original lithographs, one in color, by Juan Gris. Art dealers cannibalized a large part of the edition by removing the individual plates, framing them, and selling them, quite legitimately, as original Gris lithographs, thereby causing this title to be even rarer than its colophon would indicate.)

In the period after World War II, an entire new generation of writers emerged, and it was only natural that new areas and forms for literature would be explored. Once again, the ground breakers found acceptance difficult. Following the classic pattern, they were scorned by academics and accepted only by disciples and a knowledgeable few until the validity of their revolutionary techniques began to be recognized. The major postwar revolutionaries were Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson, and William Burroughs. These three men have obviously exerted an enormous influence on the generation of writers succeeding them. The impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on modern poetry is undeniable. It is the great watershed in American (and probably also British) poetry in the second half of this century. It has undoubtedly had as great and decisive an impact on all subsequent poetry as did Whitman’s Leaves of Grass in 1855. I do not intend by any means to claim that Howl is as great as Leaves of Grass (although there are many who feel that such a case could be made). But it is a fact that the entire course of American poetry, even poetry written by “academic poets,” was significantly altered when this poem appeared.

An even more controversial figure than Ginsberg is William Burroughs. It is probably too soon to determine how lasting his influence may be, but he is the only prose writer in English since Joyce to introduce a totally revolutionary technique—the so-called cut-up method. Many scholars, critics, and readers maintain that this is not art, or even a technique, but merely an exercise with scissors and paste. This is possibly so, but at least many writers in the two generations since the publication of The Naked Lunch—which drew praise from such diverse authors as Norman Mailer and Robert Lowell—have modeled work on his methods. At any rate, for collectors with a flair for inexpensive gambling, Burroughs presents a perfect opportunity. Virtually everything is still available, at modest prices. As of 1979 nothing had reached $100. He is still alive and often available for signing and inscribing books, and he has produced a relatively large body of work, with several items of oddball and interesting formats.

In poetry, one cannot escape consideration of Charles Olson, the most influential American poet since Ezra Pound, whom he parallels on many levels, especially in being acknowledged the paterfamilias of a large literary family. He was the founder of the now famous Black Mountain School of poetry, named for the college where he taught and expounded his theories. Many of those who flowered after World War II acknowledged their indebtedness to Olson, both publicly and by showing his influence in their work. These poets include Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley, Denise Levertov, Joel Oppenheimer, John Wieners, and Paul Blackburn, to mention only the most famous of them. The fiction writer Fielding Dawson was also a member of the group studying with Olson.

Obviously, truly revolutionary ground breakers do not often come along, but when they do, it is important for the collector to recognize them and to acquire their early work without delay.

Beginning collectors, in the first burst of enthusiasm, often tend to dissipate their energies (to say nothing of their funds) in buying without any direction or point of view, on a hit-or-miss basis. It is advisable, when beginning to collect, to lay down some sort of limits or guidelines, no matter how wide or general they may be. I remember, in my beginning days as a book collector while I was still in college, buying anything I could afford by any author I had ever heard of. The result was a hodgepodge of single titles, or at best a dozen common ones, by a great many different authors who had little or no relation to one another. For example, there was a minor play by Coleridge, a political tract by Carlyle, a minor book by John Greenleaf Whittier, a gift annual with an original contribution by Poe, two second-rate novels by Booth Tarkington (those were ex-lending library copies to boot!), a magazine appearance by Shelley, a rebound Byron, along with a few books each by Steinbeck, Hemingway, and Erskine Caldwell, long rows of unimportant titles by Tennyson and Browning, and several books by H. L. Mencken. It was a collection in which I took some pride at that point, since none of my acquaintances had anything like it. Of course, the fact that none of them collected first editions didn’t matter to me. But I soon learned the folly of trying to encompass all of British and American literature. Such an ambition requires a millionaire’s income. A beginning collector must try to work out a reasonable area of activity, and even though he may wish to collect more than one author, he should think carefully about the systematic acquisition of items. If you are not going to have an in-depth collection of your author or authors, you should set some arbitrary limits. Most author collecting is limited to the primary works, that is, those that would appear in the “A” section of a bibliography. (See page 21.) Try not to be diverted by things not germane to your collection. Unless you have virtually unlimited funds (as well as unlimited space) you will find your collection filling up with unrelated items that are not only taking up room but also eating up your book budget, often making either difficult or impossible the purchase of a much needed item that suddenly appears on the market and may not be seen again for a long, long while. A systematic program is essential.

Now, manifestly, one cannot decide to acquire books in “proper” order, waiting to buy the book listed as A-4 in the author’s bibliography until one has acquired A-3. You have to be ready to buy anything you need for your collection whenever it is offered. But for this very reason it is important not to stray too far afield. High-spot collectors are less troubled by this problem, as are those assembling a first-book collection, since their aims are already by definition limited.

Incidentally, don’t ignore any bibliography on your author that may be available. From even the poorest of them you will gain valuable clues about possible variant editions as well as about unusual, elusive, or ephemeral materials that might otherwise escape your attention.

Many reasons are constantly being put forth to justify the collecting of books, especially first editions. They strike me as quite unnecessary. Scholarly values, investment possibilities—these are all side issues. There is, when you come right down to it, only one basic reason for collecting anything, be it first editions, stamps, coins, Indian arrowheads, baseball cards, or whatever else you like—that is, that it’s fun. If you collect for other reasons, all well and good, but you are probably missing out on the best part. All you need is patience, which is necessary for any truly great love affair. Which is exactly what collecting books has always seemed to me—an ongoing affair that never palls, and one that is constantly offering new delights with the arrival of every book, every author.