CHAPTER TWO

HOW TO BUILD AN AUTHOR COLLECTION

Most first-edition collecting is author-oriented. If you collect the work of only one author or a small handful of authors, you can go into far greater depth than if you collect many authors or try to cover a wide area. In my experience, very few collectors are able to limit themselves strictly to a single author, but the author collection is the base type of most important accumulations of books.

As I have said, any collection usually starts before you realize you are actually collecting. You read a book that you especially admire, and then, when its writer publishes a new book, you buy it at once because you are anxious to read it. Chances are that it will be a first edition, particularly if you have purchased it right after publication. This may happen with two or three successive books and, without realizing it, you have the nucleus of a collection—two or three first editions. By then you may be interested enough in your author’s work to search for his earlier writings, but when you start looking for them you are disappointed to find that they are o.p.—out of print. Your regular bookseller cannot supply them. So you turn to the used, or secondhand, dealers, and probably find to your surprise that they are also unable to supply any of the titles, particularly if your author is one who has attracted some notice. One of these dealers may suggest that you try a first-edition specialist.

You go to one of these and discover, with mixed emotions, that, indeed, there on his shelves are those elusive early books. Marvelous! But then comes a slight shock when you learn that you will have to pay a premium for them, anywhere from double the original price on up to lord knows what, depending upon the popularity of your author and the scarcity of the book. You gulp, but take the plunge and buy one. And there you are. You’re now a first-edition collector, and life will never be quite the same again. If the experience is as heady a one for you as it is for most people, you will find it so satisfying, so stimulating, that you will most likely return for another expensive title before you’ve finished reading the first one. The race is on.

At this point, a sensible move is to consult a bibliography of your chosen author, assuming there is one. (See Chapter 10.) It is now standard bibliographic practice to categorize literary material in terms of its character and the author’s involvement with it, and understanding the way items are listed in an author bibliography will help you set up your collecting priorities. You have begun with books in the so-called A section. Here are listed all works by an author in their first appearance in whatever format he and his publisher decided to employ—a hardbound book, a paperback, a small pamphlet, or even a single sheet called a broadside. Section A of an author bibliography also includes works that are joint efforts by two authors, but not books to which an author has merely made a contribution. For example, at the very beginning of Gertrude Stein’s career, while she was still in medical school at Johns Hopkins University, she cooperated with a fellow student named Leon Solomons in writing a scientific article entitled “Normal Motor Automatism.” This eventually appeared in book form under the title Motor Automatism and is thus listed in my Stein bibliography in the A section. Another example of joint authorship to be found in the A section of a bibliography is The Nature of a Crime by Joseph Conrad and Ford Madox Hueffer (who later changed his name to Ford Madox Ford).

However, books that contain the work of several authors, such as the annual “best poems” or “best short stories” collections, appear in the B section. For example, there appeared in Paris in 1925 a volume called The Contact Collection of Contemporary Writers. It was published by the Contact Press to give a boost to the careers of such comparatively unknown and struggling young writers as Hemingway, Joyce, Djuna Barnes, William Carlos Williams, and Gertrude Stein. Since each contributed only a few pages and did not work with the others on any of the contents, this is a B section item in bibliographies devoted to any one of these writers.

With anthologies, incidentally, a great deal of care must be taken to ascertain whether the contribution appears in the book for the first time, or if it is merely being reprinted from a previous book appearance. Generally, reprinted items have little value or interest to collectors unless the author has altered the text for the new edition. Certain authors never go back and revise, while others seize every fresh opportunity for making revisions. Among recent poets, Marianne Moore and W. H. Auden were notorious for altering poems every time one was reprinted, thus making the establishment of a definitive text virtually impossible for scholars and providing collectors with either a headache or a field day, depending on your point of view. In fact, Auden once declared “a poem is never finished—only abandoned.” In the B section you will encounter a great deal of interesting material that may never find its way into print in any other form, even in collected editions of an author’s work. This is particularly true of forewords and prefaces to other writers’ books, and variant forms of poems that poets sometimes either forget about when issuing a new volume or prefer to suppress.

The third category in an author bibliography—and in a definitive author collection—is the C section: appearances in magazines, journals, and periodicals. The search for such publications presents the collector with much more of a challenge than the search for books, since many dealers do not take the trouble to carry them. But with a few exceptions, they are not unduly expensive, particularly if you are looking for the work of a current author. Here the aid of a bibliography is virtually indispensable. Yet lacking a bibliography (and many contemporary authors have not been made the subject of a bibliography), there are, fortunately, other sources of information. During the past few decades prior publication information has appeared on the copyright page of a book. In the case of volumes of poetry, it has become common practice to credit the individual magazines where certain poems first appeared. While the specific issues or dates of these magazines are not mentioned, you usually have a definite span of years in which to search, bounded by the date of issuance of the current book and the date of the poet’s previous volume. Usually all of the poems in the new volume will have been published between those two dates. You can then check complete runs of the named periodicals to pin down specific issues. Libraries in the larger cities and universities usually have magazine files with either the actual bound copies or microfilms.

Another source of information is the Periodical Index. While this does not cover every little magazine, it does index the major periodicals rather thoroughly, and a quick check under your author’s name will suffice. This index is issued quarterly, and can be found in the reference department of most major libraries.

For a few authors, there are also newsletters, usually edited by one or more avid fans. These newsletters often act as centers for the dissemination of news concerning appearances in periodicals and magazines. Menckeniana, the magazine devoted to lore by and about H. L. Mencken, even prints long lists of references to Mencken appearing in newspapers and magazines. Your first-edition dealer will, in all probability, know about the various author-oriented newsletters and may even carry them in stock.

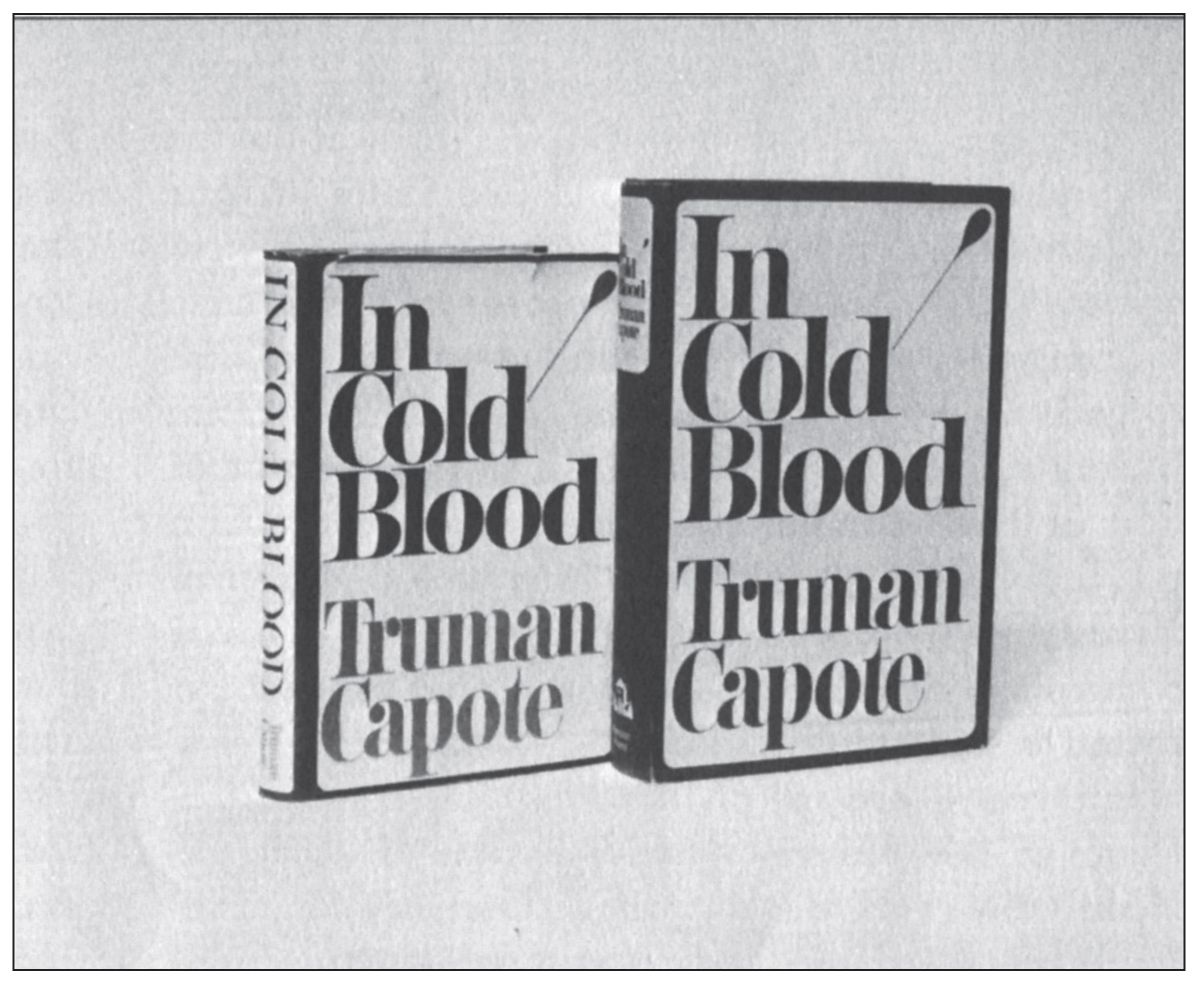

Many collectors feel that periodical appearances give a truer picture of the era in which a particular work was produced than the actual book itself. Certainly a good argument can be made for this proposition, especially in the case of poets. Individual poems are more likely to appear in magazines than are sections of novels, although it is of course true that novels are sometimes serialized before appearing in book form, and in some cases an entire book will appear in a single issue of a magazine. Two notable examples of this are John Hersey’s Hiroshima, which filled an entire issue of The New Yorker, and Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, which appeared complete in a single issue of Life magazine. Sometimes the magazine version will be revised considerably by the author before book publication, as was Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. The text that appeared in four successive issues of The New Yorker differs considerably from that of the Random House edition.

The contents of an issue of an old magazine may show some surprising literary conjunctions. For example, transition, one of the classic little magazines, is almost universally thought of as the more or less official house organ of the Paris expatriates, publishing as it did Joyce, Stein, Williams, Hemingway, Boyle, MacLeish, Crane, McAlmon, H.D., Bryher, et al. It may come as a distinct surprise to find in the later issues such writers as James Agee, Muriel Rukeyser, Randall Jarrell, and Dylan Thomas sharing space with Joyce, Beckett, and others who are generally thought of as belonging to entirely different generations and traditions.

Small but illuminating sidelights are the advertisements in the magazines, which usually give the flavor of the period more immediately and more graphically than the mere printed words. One gets also an instant perspective on the literary standing of the author at any particular time by observing the placement of his piece in the magazine. William Faulkner contributed many of his best stories to The Atlantic Monthly and to Harper’s Magazine in the 1930s. In those days the covers of both magazines carried the table of contents, listing titles and authors, in some semblance of what the editors thought was the proper order of importance. Most of the time Faulkner’s name did not appear on the cover at all, and when it did it was in the “also ran” category, a catchall in small type at the bottom of the page, usually reading “Also stories by John Doe, Jim Smith, William Faulkner,” etc. The important names were such now-forgotten giants as William Beebe, George Davis, and Gerald Johnson.

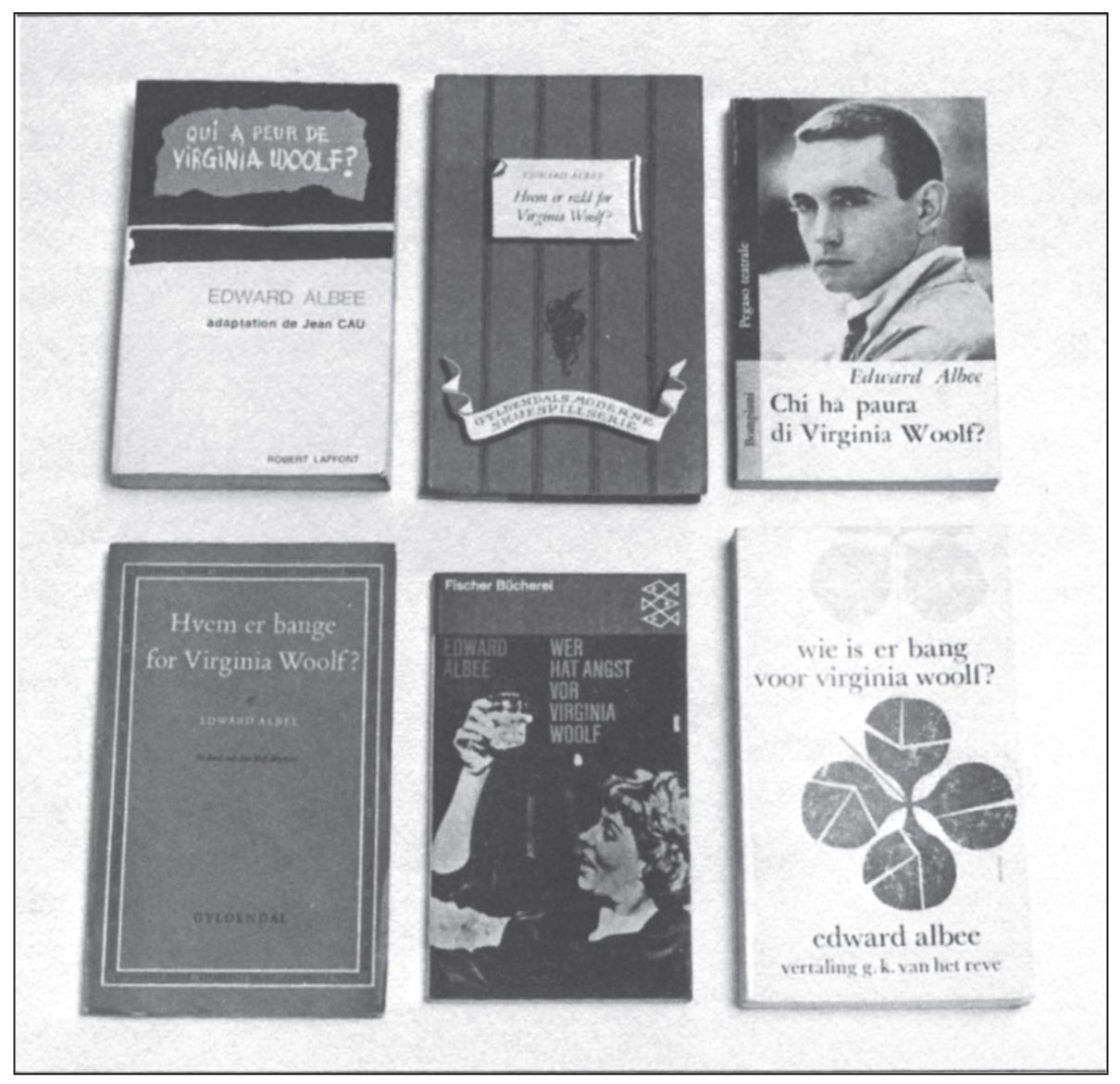

The next category of an author bibliography, the D section, is customarily devoted to foreign translations of an author’s works. Many collectors ignore these on the grounds that they cannot read them, although this seems unwise if you are aiming for a truly complete author collection. It is a field that will provide some surprises, both as to what languages your author appears in, and also as to which of his works have been translated at all. This is another area in which precise information is hard to come by without a bibliography for guidance. There are, however, a couple of aids of great value. Beginning in 1948, the United Nations required its members to report on the issuance of translations of works by citizens of the other member nations. These reports are published annually by Unesco and, happily, are indexed by author. Most large libraries have this volume, catalogued under the title Index Translationum. Of course, locating the actual copies of the translations presents another problem, which can be tackled in a variety of ways. First, and easiest, is your specialist first-edition dealer. Many of the more advanced dealers travel a good bit and pick up such titles for their stock simply as a matter of good business. Many major American cities have foreign language book-shops that carry translations from English. Finally, it is possible to write directly to the publishers in the various countries. The Unesco volume gives their names. It is surprising how many items can be obtained this way. When Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood became a worldwide sensation, it was translated into at least forty languages. By writing to the publishers of all those that I could learn of, I was able to obtain copies of virtually every one. Only one publisher failed to respond; possibly my letter never reached him.

Foreign editions of Edward Albee’s WHO’S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF? in French, Norwegian, Italian, Danish, German, and Dutch. From the author’s collection.

Some of the larger nations of the world, particularly England and France, also issue an annual volume listing all books published in those countries each year, a book similar to the American Library of Congress Register of Copyrights. These volumes will also yield information on foreign editions. The British volume is entitled The British National Bibliography.

Another form of foreign publication—which incidentally appears in the A section if the bibliographer is astute enough to note it at all—has sprung up. It causes problems for the authors and their publishers as well as for collectors. These are the notorious Taiwan book piracies. During the last twenty or twenty-five years a number of printers in Taipei have developed a flourishing business of pirating American (and British) books. They are not meant to compete with the American or British editions in their own countries; in fact, it is illegal to import them into the United States on a commercial basis. They are therefore somewhat hard for collectors to come by. Their primary purpose is to satisfy the enormous demand for books in English among students and readers in the Far East at a price that the local buyers can afford.

To produce these, an actual copy of an American book is reproduced by photo offset, printed on cheap thin paper, and usually bound in cloth. There is generally no attempt made to duplicate the original bindings, but the dust jackets are invariably photocopied, although not always in the original colors. Whatever one may think of the ethics—or lack of ethics—surrounding the issuance of these piracies, the books do exist and provide a colorful sideline for any collection. Since the entire operation is outside the law so far as the Western world is concerned, it is difficult to get dependable information on what has been issued, and you must be guided by examples appearing on the market here. Taiwan piracies of collected American authors include books by Baldwin, Bellow, Capote, Cheever, Didion, Doctorow, Gardner, Heller, Jong, Kosinski, Merton, Pynchon, Roth, Rexroth, Salinger, Snyder, Updike, Vidal, Tennessee Williams, and Faulkner, and Burgess, Fleming, Lessing, and Auden among the British—in fact, most authors of importance.

Bibliographic listings now often include musical settings of an author’s work. These will usually appear in the E section of a bibliography, the section devoted to miscellaneous items. Most common is the setting of poems to music. The composer Ned Rorem has virtually made a career of writing music for modern poetry. Here again it is difficult to discover just what has been given musical treatment. Help is available from at least two sources. The Performing Arts division of the New York Public Library, located at Lincoln Center, maintains an extensive collection of sheet music, conveniently catalogued both by composer and by author; a check of card catalog entries will reveal most of the modern musical settings of contemporary authors. The Lockwood Poetry Collection at the State University of New York at Buffalo is another repository of such settings. In fact, this library, devoted exclusively to poetry, and especially that of the twentieth century, displays the greatest strength in its chosen field of any library in the United States. Its resources are unrivaled.

A Taiwan piracy (left) of Capote’s IN COLD BLOOD compared with the regular first edition (right). From the author’s collection.

In the past three decades many recordings of authors reading their works have been issued. Prior to World War II, when only 78 rpms were available, comparatively little spoken-word recording was done. The boom began with the advent of LPs. Yale University was particularly active in this field at one point, and has issued recordings of well over one hundred modern poets. Now, with the development of tapes and cassettes, even more recordings are being made, and the older ones are being reprocessed and reissued on cassettes. Caedmon and Spoken Arts are the two principal firms engaged in this field. With few exceptions not more than one or two recordings of any particular author exist, but even one recording is of inestimable value. It is always interesting to hear an author’s own voice, and particularly enlightening to find out how he emphasizes and interprets a given line or passage that may be obscure or in dispute as to meaning. How many Shakespearean problems could be solved simply by being able to hear the Bard read the line himself! Or try to imagine Keats reading the “Ode to a Nightingale” or the “Ode on a Grecian Urn.” What wouldn’t one give for an hour’s tape of Oscar Wilde’s conversation, acknowledged by all his contemporaries to outshine his written works? But of course we must be thankful for what has been preserved, even small fragments or short passages. My own two favorite ladies, Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, were each recorded once. The Stein recording was made at the time of her triumphant return visit to the United States in 1934, and is, happily, still in print on the Caedmon label (TC 1050). Her voice is likely to come as a distinct surprise. It is a rich, colorful contralto, which she uses with great skill and modulation, to such an extent that had she not chosen to communicate in writing, it is easy to imagine her as an actress of distinction, at least on radio. The Alice Toklas record was not made until very late in her life, and may be less of a surprise than an absolute shock. From her diminutive size we might expect a chirping, birdlike voice. Instead, what comes across on the record is something resembling a bass-baritone. But what is also revealed are speech rhythms that closely approximate those of the famous Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas. Plainly this work was not wholly Gertrude Stein’s invention, but a faithful, almost uncanny reproduction on the printed page of the actual speech pattern and modulations of Alice herself. This record (Verve MG V 15017), alas, was given very little publicity at the time of its release in 1961, and very few copies were sold. In nearly fifteen years of searching, I have never located a copy apart from the one I was lucky enough to buy when it first appeared.

The E section of an author bibliography can be a real grab bag. It contains all the things not classifiable in any other category, including what are called “ephemera.” In today’s usage, particularly among book collectors, the term has come to mean a variety of oddball objects. Not all will be listed in even the best bibliography. One collector who specializes in ephemera insists that the true definition today is something that was intended to be thrown away after having served a temporary purpose. This definition comes about as close as any, and to tell the truth, I’ve failed to find any sort of ephemera that would not meet this definition. Yet many of the most fascinating items in a collection will fall into this category, and most of them can pose a huge challenge to the collector. Apart from their intrinsic interest, in some instances they provide valuable information no longer available from any other source. For instance, when Hugh Ford was gathering material for his book Published in Paris, a detailed account of the little presses that printed most of the work of the expatriates in and around Paris in the 1920s, a group of publishers’ fliers and announcements relating to books by Gertrude Stein served as a unique and valuable source of information for publication dates, prices, sizes of editions, and so forth for several of the presses being studied.

This is a virtually limitless collecting area. It can range from tangential material such as reviews of the author’s books (and other newspaper or magazine articles about him) through posters for readings; announcement fliers for forthcoming books; original photos of the author, his home, his family, his pets, and so forth; personal calling cards; even some of his personal possessions. In this latter area some judgment must be exercised. From time to time bits of clothing belonging to an author are offered for sale. Since there has been as yet no recorded instance of any of these relics’ performing miracles in the manner of saints’ relics, they have, it seems to me, dubious value, especially as there is seldom any way of authenticating their provenance. And in any event fabrics have a tendency to deteriorate at a far more rapid pace than books.

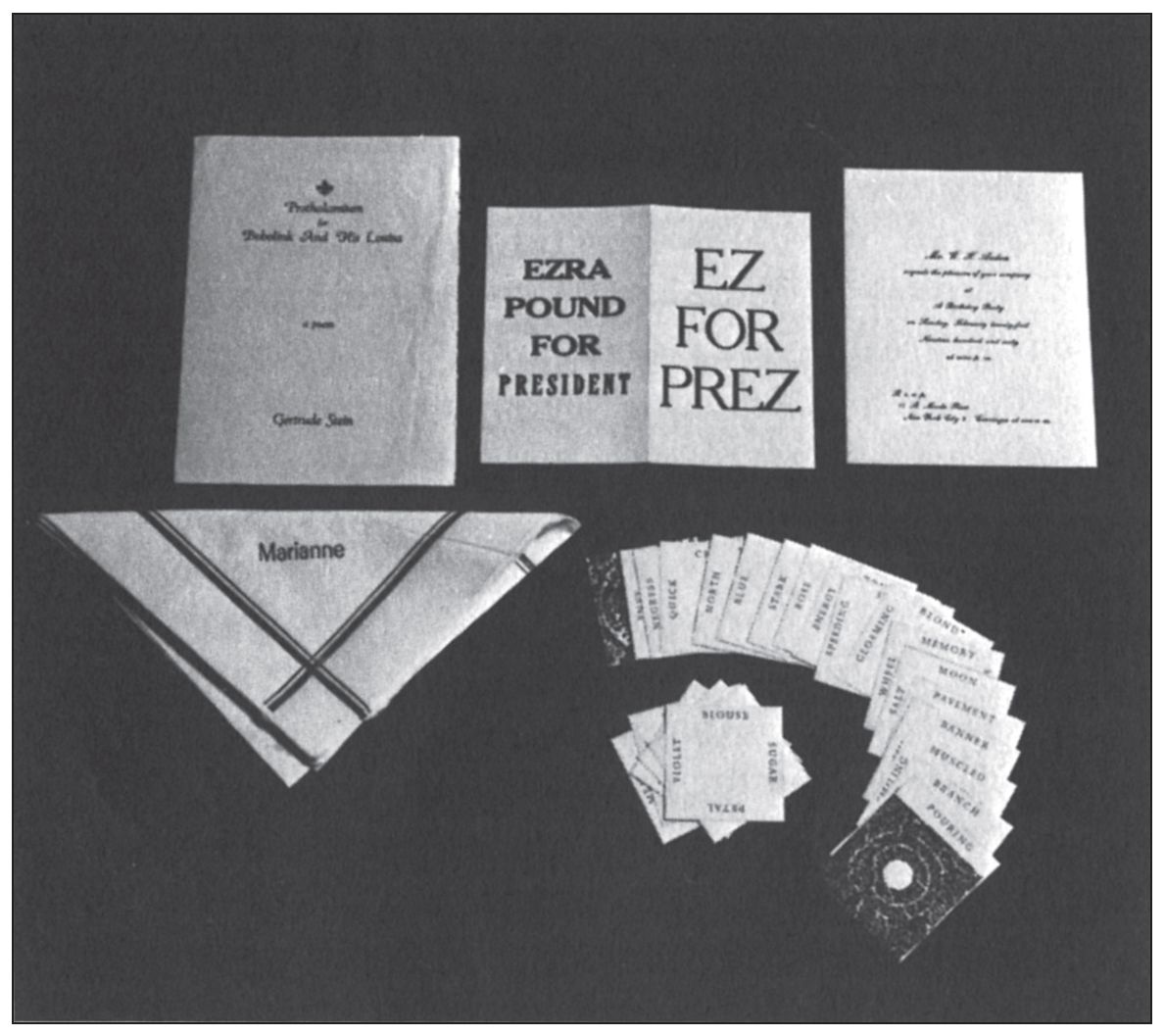

There are some items that help liven up an exhibit where an unbroken run of books, no matter how rare, may furnish dull viewing. Some bibliographies list some of this ephemera, and while such items are often the most difficult things in the entire collection to acquire, they are generally the most fun to search for. Some authors have been schoolteachers for brief periods. Eliot, Pound, and W. H. Auden served in this line, and issued mimeographed syllabuses for their courses, as well as exam papers. Many authors have been physicians; and one collector of my acquaintance prizes very highly a prescription made out by Dr. William Carlos Williams. Eliot comes to mind again for a quatrain he wrote to be printed on the back of a souvenir postcard depicting Thomas Hardy’s home. Many authors have written texts for art exhibition catalogs: Ezra Pound, Marianne Moore, Gertrude Stein, and among more recent writers, Donald Barthelme, the poet John Ashbery, and novelist Donald Windham. Gertrude Stein, as usual going everyone one step better, composed a verse to be printed on the wedding announcement of one of her protégés. (Even then, back in the 1930s, long before she was as widely collected as she is today, the demand for this item was so great that the newlyweds had to keep reprinting it to satisfy the demand from friends and admirers. As a result a total of five variants exists. The groom was enough of a bibliophile to recognize the necessity of making some distinction among them; yet this bit of ephemera, in any variant, is among the rarest of all Stein items.) In the 1930s a major New York department store sold a rug for a child’s room based on illustrations from the first edition of Stein’s immensely successful children’s book The World Is Round. And in 1977 there appeared on the market a “Stein stein,” i.e., a beer stein in the shape of what was supposed to be Gertrude’s face, with a diminutive Alice perched on the handle. Any absolutely devoted Stein collector would be delighted to have these. (The less devoted are welcome to be skeptical.)

Ezra Pound, always interested in music, very early in his career translated groups of songs from the Provençal and other languages. One group was produced specifically for Yvette Guilbert, the chanteuse immortalized by Toulouse-Lautrec. Pound’s bibliographer Donald Gallup went so far as to list this item in the B section of his book. Later on, Pound organized concerts in Paris and Rapallo, and many of the programs for these contain texts by the poet. During the war, wall placards were issued in Italy with texts by Pound.

A sampling of literary ephemera: Gertrude Stein’s wedding poem for Bobchen Haas; Ezra Pound presidential leaflet; an invitation to W. H. Auden’s birthday party; paper napkin from Marianne Moore; and a set of poem-playing cards by Michael McClure. From the author’s collection.

Yeats, with his Celtic interest in things occult, wrote two anonymous pamphlets in 1901, entitled Is the Order of R.R. & A.C. to Remain a Magical Order? and A Postscript to an Essay Entitled “Is the Order of R.R. & A.C. to Remain a Magical Order?” Miscellanea surely—and among the most difficult of all Yeatsiana to find.

Odd items about an author—as opposed to publications having texts by him—can be even more varied. A pamphlet in my collection promotes Ezra Pound for President, using the slogans “Ez for Prez” and “Let’s Have a Round Pound,” while he was still incarcerated in St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington under indictment for high treason! A greeting card issued by James Thurber contains a drawing by him depicting the moment of shock when an unusually well-endowed male makes his first appearance in a nudist colony.

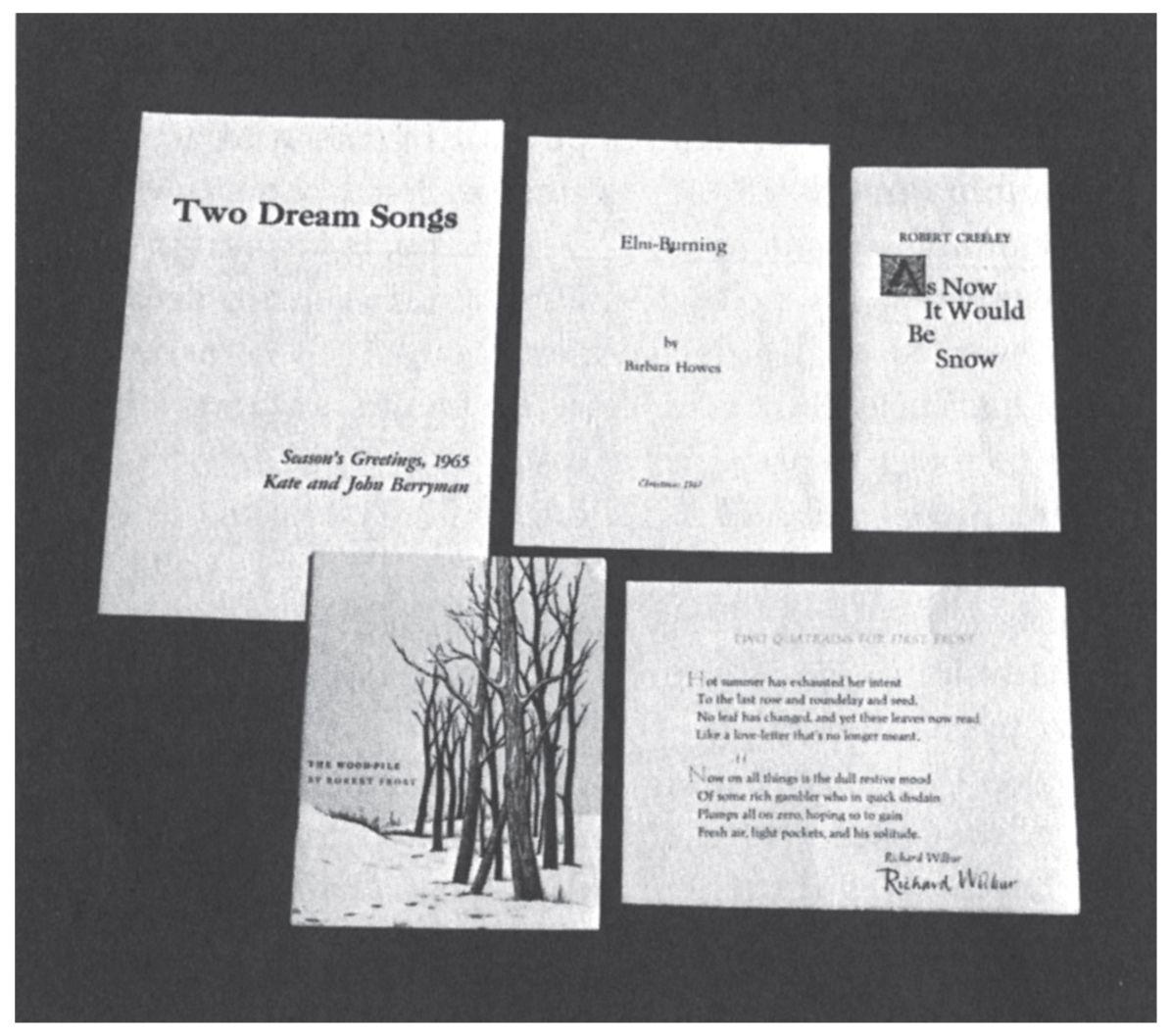

Poets are especially fond of writing and publishing their own verses as Christmas cards. Most modern poets have issued some of these, usually privately to their own circle of friends. However, Hallmark cards issued one of Auden’s commercially, as did the United Nations UNICEF program, which offered pamphlets of eight to ten pages to use as a card, with a verse by Denise Levertov. With Robert Frost, the cards became an annual commercial venture after the first few years. With the proper connections, it was possible to order a supply of the current year’s Robert Frost Christmas pamphlet with your own name imprinted thereon. There are thirty-five such Frost Christmas pamphlets, some with as many as twenty different imprints.

I could go on citing specific examples of fascinating ephemera, but I’d prefer to suggest some general areas for consideration when adding ephemera to a modern collection. First of all, with most modern books, especially those from little or private presses, there will be advance fliers or blurb sheets, or perhaps small catalogs listing or announcing these works. These can become an extremely valuable source of information to future researchers or bibliographers. Major publishing houses send out a varying number of review copies in the hopes of gaining favorable reviews or acceptance by a book club, thereby stimulating sales. These copies quite often have a photo of the author laid in, which the publishers hope will be used to illustrate the review. These photos alone are an area for specialization.

A group of poet’s Christmas pamphlets: TWO DREAM SONGS by John Berryman; ELM-BURNING by Barbara Howes; AS NOW IT WOULD BE SNOW by Robert Creeley; THE WOOD-PILE by Robert Frost; and TWO QUATRAINS FOR FIRST FROST by Richard Wilbur. From the author’s collection.

Nowadays, the more popular authors give public readings. This is especially true of poets. There are usually posters or announcements for these readings, some of which may have a photo of the author, or in some cases, a few lines of verse by him or her.

In the case of a novelist whose books are transferred to the screen, a large number of items become desirable. Easiest of all to find are the 8” x 10” stills from the picture, along with theater cards (the colored scenes from the film that are usually displayed outside the theater). For a major film there are publicity brochures put out by the studios, including sample ads for use by theaters in local papers. Most desirable of all, but the hardest to come by, is the script for the film version of the book. Sometimes scripts have been written or worked on by the authors themselves, sometimes by studio hacks, and in rare cases by major authors who are under contract to do scriptwriting. When times were hard, F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner worked as scriptwriters in Hollywood; so did Dorothy Parker, Anita Loos, Tennessee Williams, Terry Sothern, Christopher Isherwood, and Truman Capote, to mention only a few. As I have said, scripts by such people as these are most desirable, and perhaps don’t strictly belong in the ephemera category, although they were certainly not designed to be used again after having served their initial purpose. Studios guard these zealously, and very few leak out into the trade, but enough do appear to make this a much sought-after category, with prices usually in three figures.

Sometimes novels are adapted to stage performance, usually before being turned into a film. Programs for such productions form another category of association items. They are particularly rare if the stage version is short-lived, as was the Broadway version of Hemingway’s A Farewell to Arms. It lasted fewer than ten performances, automatically making a program for it very rare and consequently very high priced.

Recently the passion for illustrated T-shirts has led to several literary imprints; in some cases the authors themselves have had them made up. Poet Anne Waldman recently presented me with one bearing the cover design of her most recent book (which featured a glamorous photo of herself). This may be a sign that things are getting out of hand (the aforementioned Stein stein is another) but you will have to draw your own lines. Luckily, book collecting is not like stamp collecting, where the printed albums, with definite spaces to be filled, leave no leeway for personal judgment.

One very nice thing about ephemera is that most of it will cost very little. In fact, some of your most delightful items may even come free. A number of dealers do not want to be bothered cataloging or handling such relatively insignificant items. Many a charming item has been presented to me as a goodwill gesture by a dealer who knows of my interest in a particular author. If you have established a good relationship with a dealer, he may well do the same; after all, he hates to throw any item away, and he knows that you will like it. And keeping a customer happy is simply a matter of good business, if nothing else.