CHAPTER THREE

STARTING WITH AN UNKNOWN AUTHOR

For the beginning collector with a modest budget who cannot aspire to the gems of the twenties and thirties—now reaching price levels that only the richest collectors and the most heavily endowed universities can afford—modern book collecting may look like a discouraging field. Few people seem to realize that every author whose work is now highly esteemed and correspondingly high priced was, at one time, relatively unknown and unappreciated—and uncollected. It is here, among the unknowns of today, that the new collector can operate to greatest advantage, financially and in terms of pleasure.

The requirement here is good taste in literary matters. It is essential to read the authors you collect, and not simply assemble copies of their books. Gertrude Stein commented on this in 1933 when The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas brought her worldwide fame after nearly twenty-five years of publishing in relative obscurity, and people started collecting her books avidly. She wanted, she said, “to be read, not collected.”

The only way to spot emerging talent is to read. Read, and keep reading. A good deal of such reading of new writers will of necessity have to be done in magazines, for few if any writers have a book published until they have been published in journals for several years. Once in a while something comes along like Gone with the Wind, which had neither antecedents nor successors, but this is the exception. Poets particularly are likely to publish in periodicals, because their output is usually not of sufficient bulk or quantity to make a book until several years after they begin. After nine years of publishing poems in magazines, Marianne Moore had only enough to make a pamphlet of twenty-six pages—her first book, Poems, published in 1924. Robert Frost’s first book, A Boy’s Will, was published in England in 1913 after Frost had been writing for nearly a decade. So to begin, one must read little magazines with a finely tuned ear. How to develop such an ear can be argued endlessly—and pointlessly. I can only repeat what the opera diva Zinka Milanov told a gushing admirer who asked her how she managed to produce such lovely high C’s. Madame Milanov replied succinctly, “Dolling, either you got the voice or you don’t got the voice. I got the voice.” Yet even if you “don’t got the ear,” your taste can still be cultivated to some extent. It takes time and patience, but with any degree of sensitivity at all, you will soon be able to discern the good from the bad. Once you have savored quality, mediocrity will never again suffice.

From then on, it is simply a matter of following your chosen author’s career. Naturally, some authors—poets particularly—start off brilliantly and then seem to diminish in vigor, strength, and interest. If this happens with one of your choices, you will very likely not have spent an inordinate amount of money—although you may have invested a good amount of reading time. You will almost certainly have found some enjoyment. But all this pales into insignificance when one of your early choices keeps on improving and turns out not only to be an extraordinary poet, but also a writer who is widely recognized and acclaimed. Then you will have an almost proprietary feeling about the author you spotted long ago as a “winner,” a feeling confirmed by your own superb collection of his books, with all those early titles, now impossible to find, perhaps even inscribed to you. It may take ten or twenty years, but in the meantime you have been relishing the books, perhaps even getting to know the poet personally, and deserve to feel superior to those collectors who hadn’t the courage or taste to decide for themselves which authors were worth collecting.

If you are truly convinced from the beginning that your poet is worthwhile, I’d recommend buying two copies of each of those early works, or even more of some of them if, as is often the case, they are inexpensive pamphlets. In purchasing one you will be forming your own complete collection, one you are unlikely to want to break up later even when market demand rises. Therefore, if you have set aside two or three copies at publication, for a couple of dollars or so, you are in a position to part with them quite happily when they begin to fetch tidy sums. You can use them for bartering for expensive items otherwise unobtainable.

I spoke of the possibility of having the author’s early books inscribed to you. Within the existing framework of book collecting, there are several gradations of desirability. At the bottom is an ordinary unsigned copy of a book. One that the author has signed is definitely a notch higher in the scale, while one that bears some writing in addition to the mere signature is even more desirable. At the top of the scale is a presentation copy—that is, one actually given by the author to someone, with an inscription in his hand attesting to this. And within this top category, there are still further refinements. Copies inscribed to other well-known authors are particularly desirable, as are copies inscribed to mothers, wives, or lovers. The ne plus ultra is, of course, the dedication copy, i.e., the copy inscribed to the person to whom the book is dedicated. Obviously there can be only one such, and therefore it achieves top rank in desirability.

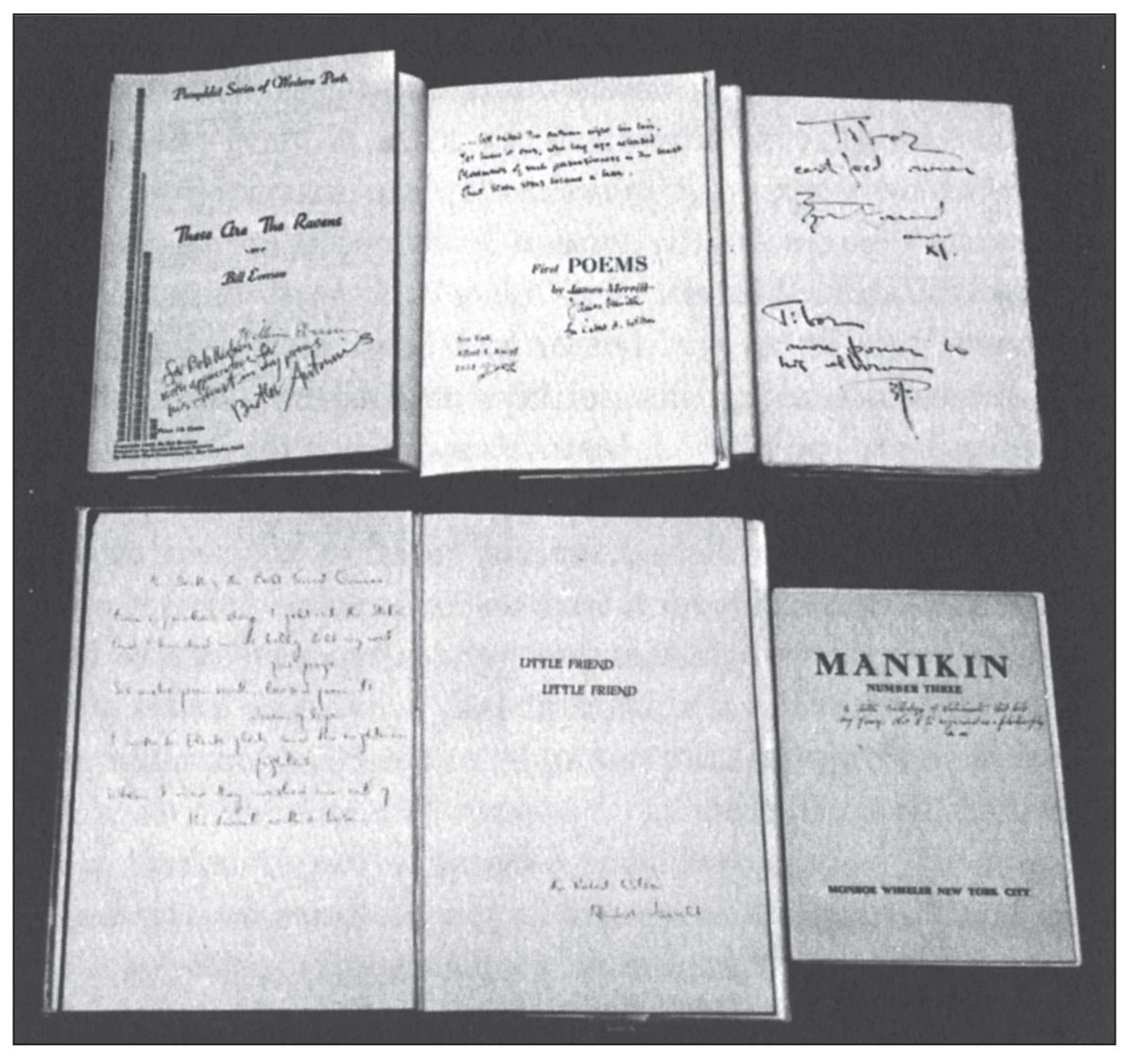

A group of inscribed books: THESE ARE THE RAVENS by William Everson (Brother Antoninus); FIRST POEMS by James Merrill; A DRAFT OF XXX CANTOS by Ezra Pound; LITTLE FRIEND, LITTLE FRIEND by Randall Jarrell; and MARRIAGE by Marianne Moore (published as Manikin #3). From the author’s collection.

Neophyte authors are always particularly anxious for recognition. This is especially true of poets, to whom fame, fortune, and recognition come much more slowly than to novelists or playwrights. They are usually extraordinarily grateful when anyone evinces any interest in them at all. A simple letter to a young poet telling him how much you have enjoyed his work, and asking, at the same time, if he would be willing to inscribe your copies of his first two or three books seldom fails to succeed. In many cases the gesture can be the foundation of an interesting and fruitful acquaintance. Quite often poets will have printed some little pamphlet or broadside for their personal use, and they may be willing to give you copies of these if you simply ask about them. More often than not, inscriptions made in the early days of a poet’s career, before he is chastened by fame, will be either lengthy or charming, or both. A good example of just what can happen if you develop an interest in a young poet’s work early in his career is exemplified in my collection of James Merrill, the American poet who won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975. Merrill had been publishing poetry ever since his undergraduate days at Amherst, and had his first regularly published book issued by Alfred A. Knopf in 1951, a volume entitled simply First Poems. In the succeeding years he published several volumes of verse, as well as two novels, one of which bore on its dust jacket high praise from Truman Capote, an author generally not given to lauding a competitor’s work. Merrill had over these years a substantial reading public, enough to justify reprintings of many of his earlier books of poetry. While he was collected to some degree, he was never strongly sought after. However, the Pulitzer Prize award, as it sometimes does, changed all that, and now he is widely and eagerly collected. The prices for his early books double and triple every few months, it seems. Collectors now know that First Poems was not, in fact, his first, book, but his third. The true first, entitled Jim’s Book, was a substantial hardbound affair, privately published by his father for the family and close friends. It is a book of poems and short stories, all juvenilia, published in 1942 when the author was only sixteen. The work shows talent, but the poet himself considers it immature, prefers to ignore its existence, and is reluctant even to reply to inquiries about it. Since it was a privately published item, intended as a surprise for the author, never for sale, it is of extreme rarity.

Merrill’s second book, which appeared some four years later in Athens, was a long poem entitled The Black Swan, again privately printed, this time by the poet himself in an edition of only one hundred copies. Since then he has personally published at least one other such long poem in pamphlet form for his personal use, as well as an amusing quatrain on a small card for his mother’s use in acknowledging congratulations on his having won the Pulitzer Prize. None of these was ever for sale, and while some of them eventually work their way into dealers’ catalogs, it is always an isolated copy that appears on the market, for which there are always many customers. If you become friendly with the poet, there is a chance that such items will be given to you. One of these little pamphlets in my own collection bears a poignant inscription: “For Robert Wilson, my faithful, perhaps only reader, from James Merrill.” I bought those extraordinarily rare first two books from another book dealer at a time when Merrill was still not very actively collected. The price was nominal, and the dealer seemed glad to be rid of them—despite the fact that Jim’s Book was nothing less than the dedication copy! (Late in 1978, the only copy of Jim’s Book to have appeared in a dealer’s catalog thus far was priced at $4,000.)

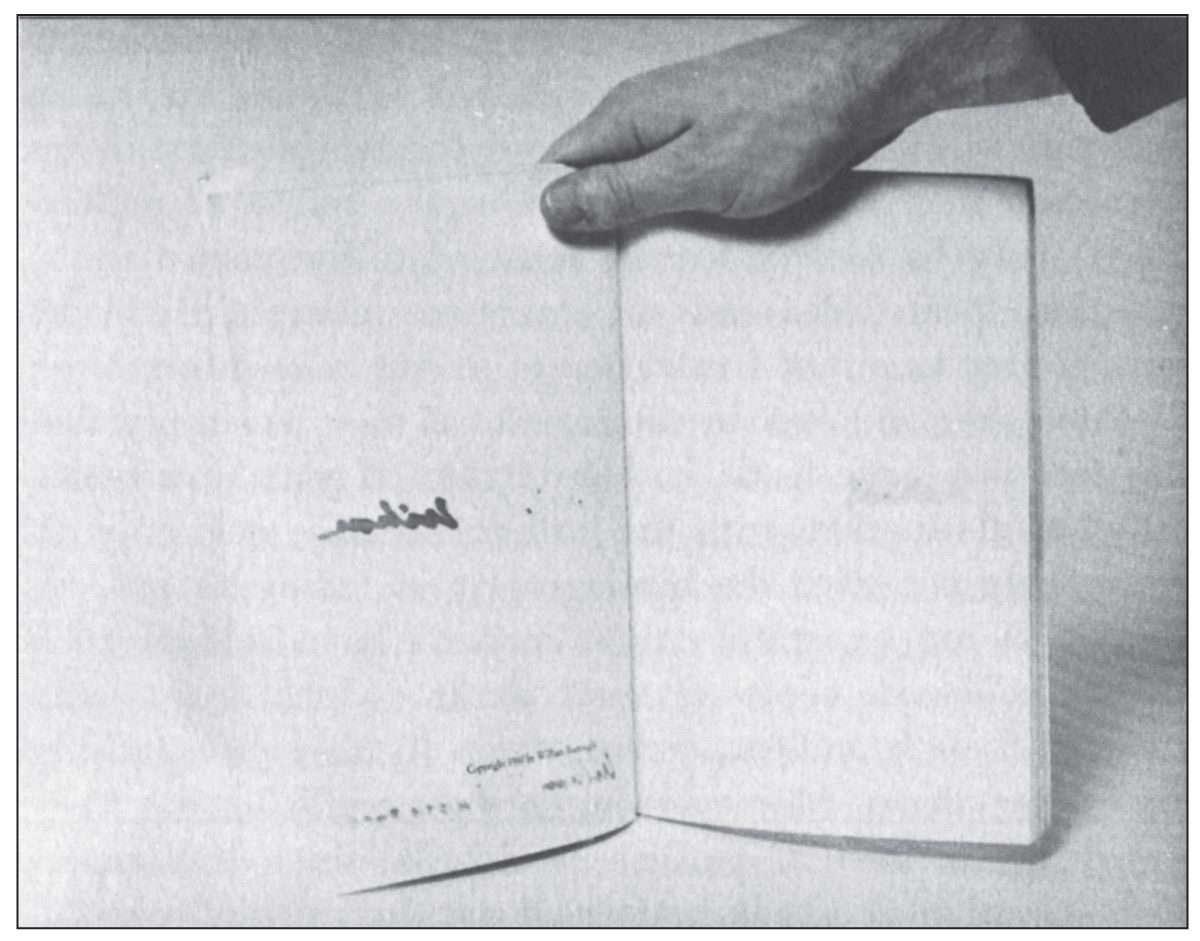

In my experience, even world-famous and well-established poets can be generous with their time. Two of the very biggest names in twentieth-century poetry, W. H. Auden and Marianne Moore, rarely if ever refused any request they could grant in the way of signing books. They were cooperative even when the signing request involved many volumes, and they invariably invited the importuner into their homes, thereby giving up even more time. A few poets are totally reclusive; Wallace Stevens would not allow even his publisher, Alfred A. Knopf, into the house, but entertained him on the lawn. But such extreme cases are rare. When having books signed by an author, if possible provide the pen yourself. Preferably, if you can find one, use an old-fashioned fountain pen with ordinary ink. A cartridge pen can be used in a pinch. The use of ball-point pens or felt-tip pens is fraught with several dangers. The ink of felt-tip pens tends to fade quickly, and the pressure needed to make a ball-point pen work usually makes deep grooves or impressions on the underlying pages. Especially on soft book paper, felt-tip ink may spread or bleed through adjoining pages. I learned this the hard way when William Burroughs generously inscribed a group of books for me. Being in a breezy mood that day, he employed four different colors of felt-tip pens. I was delighted at the time, since the multiple colors made a brilliant display on the various title pages. But when I went to show these inscriptions to another collector only a few months later, I discovered that the colors had bled through as many as eight pages on either side of the inscription, rather diminishing my joy. Many authors will have their own pens, but if you have your pen ready, most of them will accept it. And not a few will absentmindedly make off with it as well, so it’s best not to offer an expensive model. If you are getting books signed after a reading or other public appearance, try to remember that many other people also want books signed, and an author’s time and patience have their limits. Generally speaking, two or at the most three books is as many as one should ask to have signed at a time. Sometimes the author is anxious to leave promptly and will suggest that you deliver or send the books to his residence. If you do this, be careful to make the process as convenient as possible for him. Provide a return address label, fresh gummed tape for resealing the parcel, and of course, sufficient postage for the return journey. After all, authors need their time for writing. Try not to be another person from Porlock.

Some poets who become aware of your devotion to their work will send you advance information or announcements of their forthcoming books. Some even send complimentary copies, and it is not unknown for a poet to bestow work sheets or manuscripts upon really earnest enthusiasts.

The consequences of using a felt-tip pen for autographing—bleed-through in ink on a copy of William Burroughs’ THE EXTERMINATOR. From the author’s collection.

Paying attention to a rising poet or author for many years may bring about events that you could scarcely have foreseen. Once it becomes known in the book-collecting world that you are particularly interested in a certain author, dealers will often offer you special items in advance of putting them in a catalog. Conversely, dealers will also begin to ask you for specific information on bibliographical fine points or variants with which they are personally unfamiliar, especially where no bibliography exists. Thus, by degrees, you may begin to gain a reputation for expertise on your author. You may be the expert. This has been known to lead the collector to produce a bibliography of the author in question. It should be noted in passing that bibliographies are generally not moneymakers, particularly if you count the time expended in gathering the necessary minutiae. But at some point or other, it is almost inevitable that you will wish to set down and codify the mass of information that you have gathered in the course of collecting. It may be merely from a sense of self-preservation, to stop the repeated demands on your time to explain odd details; it may be out of frustration at seeing false information repeated over and over in catalogs; or it may be simply that you feel you have to do it. Here again, if you have established a relationship with the author, he may well be willing to help out with the bibliography so far as he can, although in my experience most authors have seldom been able to hold onto copies of their works (which are usually given to their friends or, worse, stolen by them), especially the earlier pieces. Moreover, authors generally have a hazy knowledge at best of publishing details, since this aspect of the creation of a book is after all not their prime concern.

In a few cases friendship with the author and his work may bring still closer involvement. It is not unknown for a fan to become either a part-time or even a full-time secretary to an author, and in a couple of notable instances, a lifetime companion, as witness Clara Svendsen’s long association with Isak Dinesen. Alice Toklas began her relationship with Gertrude Stein as a part-time typist of Stein’s voluminous longhand works. And recently, a young professor, cocompiler of a bibliography of one of the century’s major poets, found himself gradually moving into a closer relationship with the poet, eventually editing his later volumes of prose, and after the writer’s death winding up as his literary executor. Now none of these things is guaranteed to happen (and you may not even want any of them to happen) but experience shows that they are entirely possible.

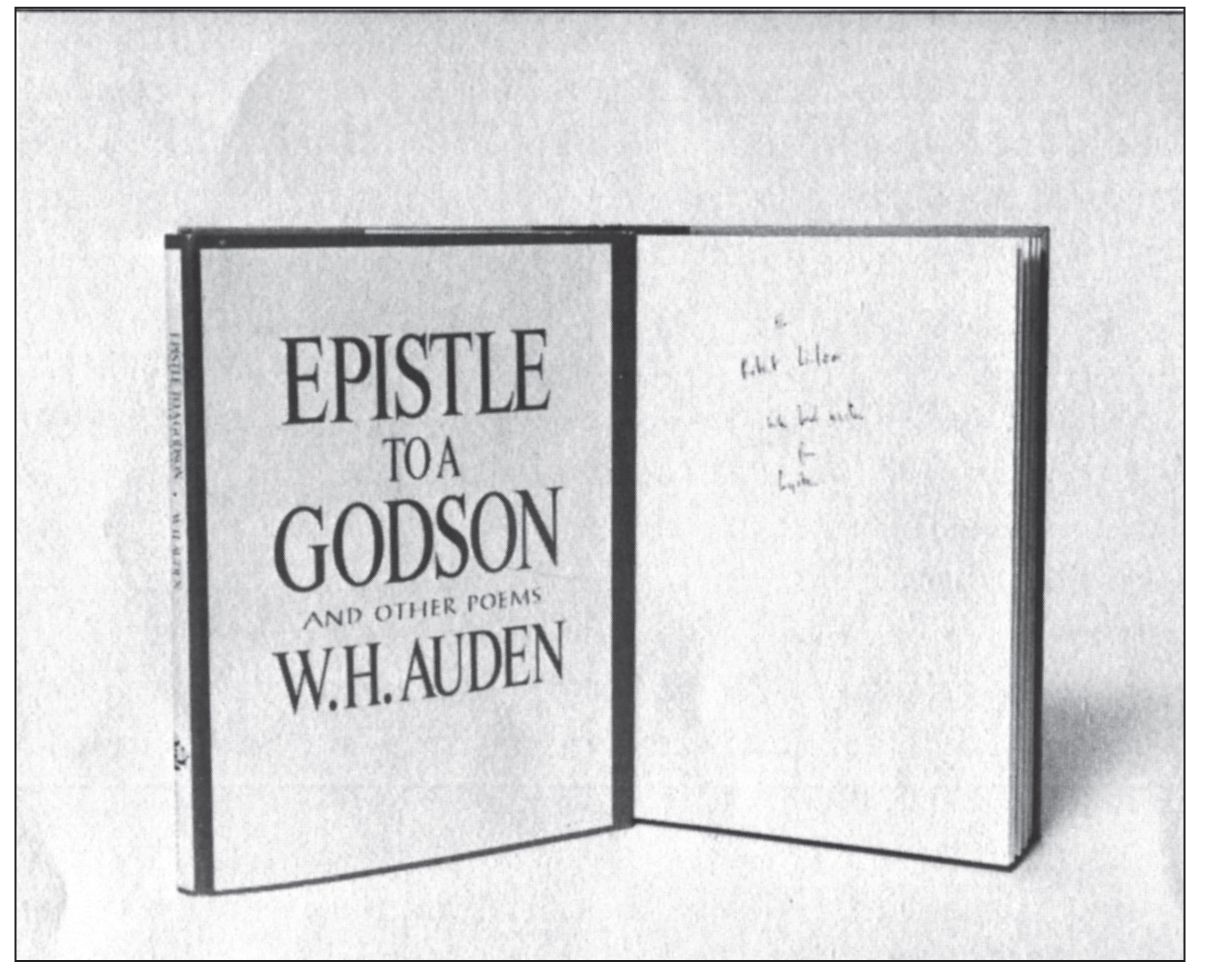

W. H. Auden’s last book, with an inscription to the author. From the author’s collection.

In my own case, a friendship with W. H. Auden grew out of a simple request to have him sign my copies of his books, which at that time numbered perhaps a dozen titles. He was kind enough to invite me to bring them to his apartment on St. Mark’s Place, in New York’s East Village, at teatime. Tea turned out to mean cocktails—very strong martinis, in fact. Emboldened by his agreeableness, I applied to him again, a year or so later, when I had added further titles to my collection. Again he was lavish with his time. As the years went on, this became a ritual, and I would see him every six months or so. We eventually reached the point where, when I mentioned that I had never been able to find such-and-such a title, he would invariably offer to give it to me if he could find it. Finding it, of course, was the problem; search as he would he could rarely locate the book on his shelves, even though he often looked assiduously. Auden lived in a shambles that had to be witnessed to be believed. His furniture was dilapidated to the point where the springs had burst through the worn fabric of both the sofa and the single easy chair; the padding was oozing out of vital spots in both pieces of furniture, and the end of the sofa was held in place by some tall panels from a packing crate. Piled everywhere were disorderly accumulations of phonograph records, books, magazines, and working drafts of manuscripts. On one unforgettable occasion, he did manage to turn up one of the rarest items in the canon of his work, a tiny pamphlet entitled simply Poem, published in 1935 in an edition of only twenty-two copies. He gave it to me.

In 1972, when Auden finally decided to leave America and go back to England, our friendship was firm enough for him to ask me, as a dealer, if I would be interested in purchasing the portion of his library that he did not want to take with him. Of course, I agreed immediately. He then said, “Mind you, I don’t have any first editions. I’m not a collector.” I agreed nevertheless, realizing that even though his attitude toward books as objects was as far from a book collector’s as it is possible to be, there would, of necessity, have to be some first editions—and lord knows what else.

Eventually the time came for him to start the immense task of transplanting himself. When I arrived he had sorted out the books he wanted to keep, piling them in heaps on the floor. Everything else was still on shelves and tables, in every one of the four rooms of his apartment. I looked around and said that it would take me about a week to give him an estimate of what I could pay for the library. He looked a bit surprised. “My good man,” he said, “I don’t want an estimate. Just get the stuff out of here so that I can start packing. Take it away and send me whatever you think proper.” It took the better part of two weeks simply to pack up and move the books. During the course of this work I gained enough courage to ask him why he had chosen me, when any dealer in the world would have jumped at the opportunity. His reply was very matter-of-fact. “Because you’re the only one who has taken a personal interest in my work.” Needless to say, his library contained, along with what he described as “the world’s largest collection of terrible poetry” (wished on him by aspiring poets), some great plums.

Nor was this the only instance of such a happening. I acquired Marianne Moore’s library through a similar chain of events. I had made her acquaintance before I met Auden, and long before I had any ideas about becoming a professional book dealer. She was one of the first poets I ever asked to sign books for me. She apparently liked me well enough to allow me to come back from time to time over the years, and once even prepared a memorable, if peculiar, luncheon for me, composed of all the leftovers in her refrigerator. Toward the end of her life, when her family forced her to move back to Manhattan from the disintegrating neighborhood in Brooklyn where she had resided for a quarter of a century, she allowed me to buy several shopping bags full of items she no longer wanted. They ranged from back issues of magazines up through presentation copies of rare books by H. D., William Carlos Williams, and T. S. Eliot. Later, I was entrusted with the job of placing her archive in an institution. As with Auden, this enviable opportunity came about because I had collected her books and ventured to have them signed.

While it is certainly enjoyable and even thrilling when one of your authors rises to immense fame, it is not necessarily disastrous when it fails to happen. A forest is not composed solely of giant trees. It takes all grades and types of writers to make up a literary milieu at any given time. Many authors of less than monumental importance are nonetheless interesting, even if their works are not major landmarks of literature. The giants of course attract the lion’s share of the attention with collectors, both private and institutional, but eventually the time comes when scholars and collectors begin to see the charm and importance of some of the lesser lights. One example of this can be seen in the complete exhaustion of possible discoveries in the work of the expatriate authors of the twenties. Hemingway and Fitzgerald have been worked over to the point where there are few finds to be made. But as late as the mid-1960s, the books of Harry Crosby, published by his own Black Sun Press, were literally going begging. I saw stacks of them in a New York bookshop at $4 per copy—with no buyers. And while half a dozen years ago there was some interest in Djuna Barnes, Robert McAlmon, Mary Butts, and others of the period, most of their books could be found easily and were not expensive. Today interest in all these secondary authors is extremely keen, with virtually no copies available of any title. When the occasional copy does surface, the price is high and the demand brisk. So don’t be disappointed if your author does not become a giant. As long as there is true literary quality in his work, the collection will always be of interest and value. In fact, because it is focused on a less-collected author, you may find that an institution is much more interested in having it than in acquiring yet another collection of the works of one of the more famous names. It probably already has the latter books—likely in multiple copies.