CHAPTER ELEVEN

A BOOK PRODUCTION

In an earlier chapter, mention was made of galleys, proof copies, advance reading copies, and such other items involved in the production of a book which precede actual publication. Since the nature and function of these objects are often confused or misunderstood, even by some dealers (to say nothing of beginning collectors), this chapter will be devoted to a step-by-step account of the process by which an author’s manuscript becomes a book. An understanding of it is more important than it once was; book collectors have become more sophisticated in their tastes and interests in the past couple of decades. Prior to World War II, one collected first editions, period. Virtually no one paid any attention to anything else—either later editions, or earlier states or forms of a book—other than the actual first edition as issued. Later revisions, variant bindings, and the like were never listed in catalogs and were apparently regarded as lacking in significance. Likewise, states of a book before the final, published format were not collected at all. Yet these preliminary states often reflect earlier versions of the text and are in many respects of great interest, scholarly and otherwise. Nowadays such early state material is keenly sought after.

While the basic processes involved in making most books are consistent, there are many variations. For example, works of nonfiction generally involve matter that does not appear in works of fiction—indexes, appendixes, forewords, introductions (although sometimes works of fiction by new authors have introductions by better-known, well-established authors), tables of contents, illustrations, etc. However, as most collected books are fiction (or poetry), the following description involves the production of a typical novel.

Naturally, the first step is for the author to submit a completed manuscript to the publisher. No matter whether or not this is a cleanly typed text, it is generally known as a rough working manuscript. It may be an actual manuscript in the original sense of the word—that is, handwritten—although this is highly unlikely; most publishers insist on typed copy. Most standard contracts, in fact, call for two sets of finished manuscript. At one time this consisted of the ribbon original and a carbon typescript. This still tends to be the case in England, but nowadays in the United States the submission generally consists of the original typescript and a photocopy. Quite often, in fact, contemporary authors submit only the original copy of their manuscript, assuming that the publishing firm will have its own photocopying machine and can run off copies readily. The submitted manuscript may itself be a photocopy, since the author will usually want to keep at least one copy himself, for obvious reasons. The final copy submitted to the publisher, whether original typescript or photocopy, may have some last minute corrections in the author’s hand.

Having received the original from the author, the publisher proceeds to make photocopies for internal house use, usually five or six of them. These will be used to plan the book in the production department, to prepare a book design in the art department, and to begin work on a jacket, either inside the house or with an outside artist. Other copies go to various persons in the office for reading or scanning. The book’s editor uses one for his editing, and he will probably go through these changes with the author, ultimately transferring them to the original copy (by now known as the “setting copy”—the copy of the manuscript that will go to the typesetters). At this point a copy editor must read through this top copy, or setting copy, correcting any punctuation or spelling errors and making style consistent. Once again, the author must read through the copy to make sure that he approves all the items marked before it goes to the typesetters. He also has an opportunity now to make final changes of his own. If the revisions have been extensive, it may be necessary to retype the entire manuscript. This will seldom happen, although a glance at a single page of revisions made at this point by James Joyce makes one wonder how Maurice Darantière’s typesetters managed to decipher anything at all when setting type for Ulysses, the more especially in view of the fact that they were setting in a language unknown to them.

More likely it is an odd page or two that would be retyped and inserted in place of the one bearing numerous corrections. All of these changes will appear on the setting copy, but no effort will be made to correct the photocopies of the original text that went to the production departments. They usually remain uncorrected, since textual revisions will rarely affect the work of the jacket design department or even the physical makeup of the book. (Unless, of course, the changes are so extensive as to require that the book itself be redesigned. This is very rare.)

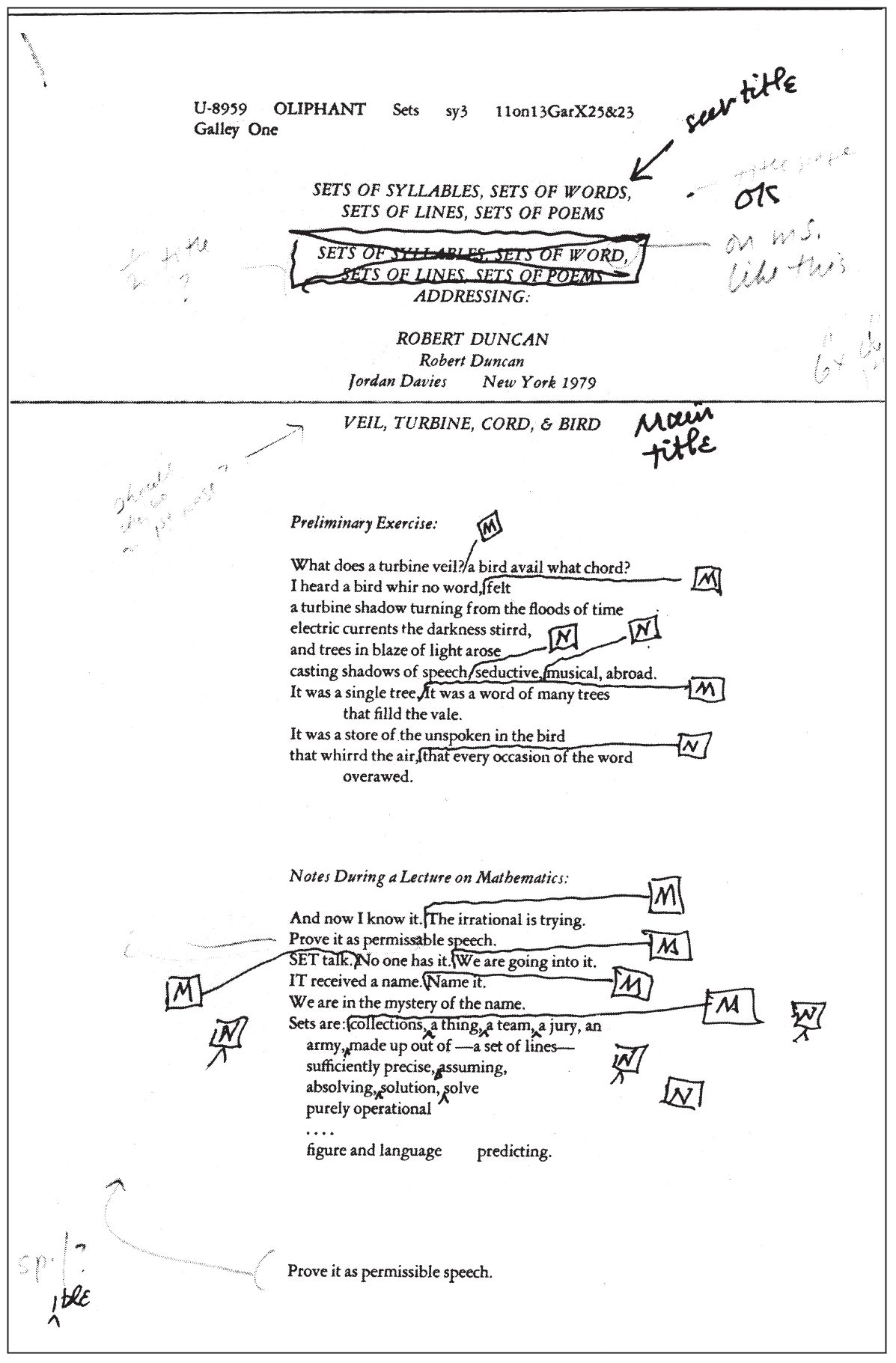

Finally, typesetting takes place. Once the type has been set, the printer pulls about three sets of loose galleys, or long galleys, called such because they are printed on long sheets of proof paper, each sheet bearing approximately two and a half printed pages. (If the book is being set, as is increasingly the case, by a computer, the long galleys may come through at this stage already broken into single pages.) These are then read by the author, by a professional proofreader, and sometimes by the book’s editor. To distinguish the source of changes made at this stage, each set of galleys is generally marked at the top of the first sheet—for example, “Author’s set.” The various corrections are then collated and transferred to one master set. This may or may not be the author’s set. One reason for the importance of identifying the corrections at this point is the matter of financial responsibility for the changes. Since typesetting, like everything else, is a costly matter, the publisher quite naturally wishes to avoid expensive changes insofar as possible. The errors of the typesetter—PEs—are legitimately his expense. However, if the author has made errors, or wishes to make changes in the text originally submitted, these are known as author’s alterations—AAs—and the cost of making them, beyond a certain reasonable number, will be charged to the author’s account. The final corrected set then goes back to the printer, who will make the corrections.

First page of a set of author’s galleys, corrected by the poet Robert Duncan. Courtesy of Jordan Davies.

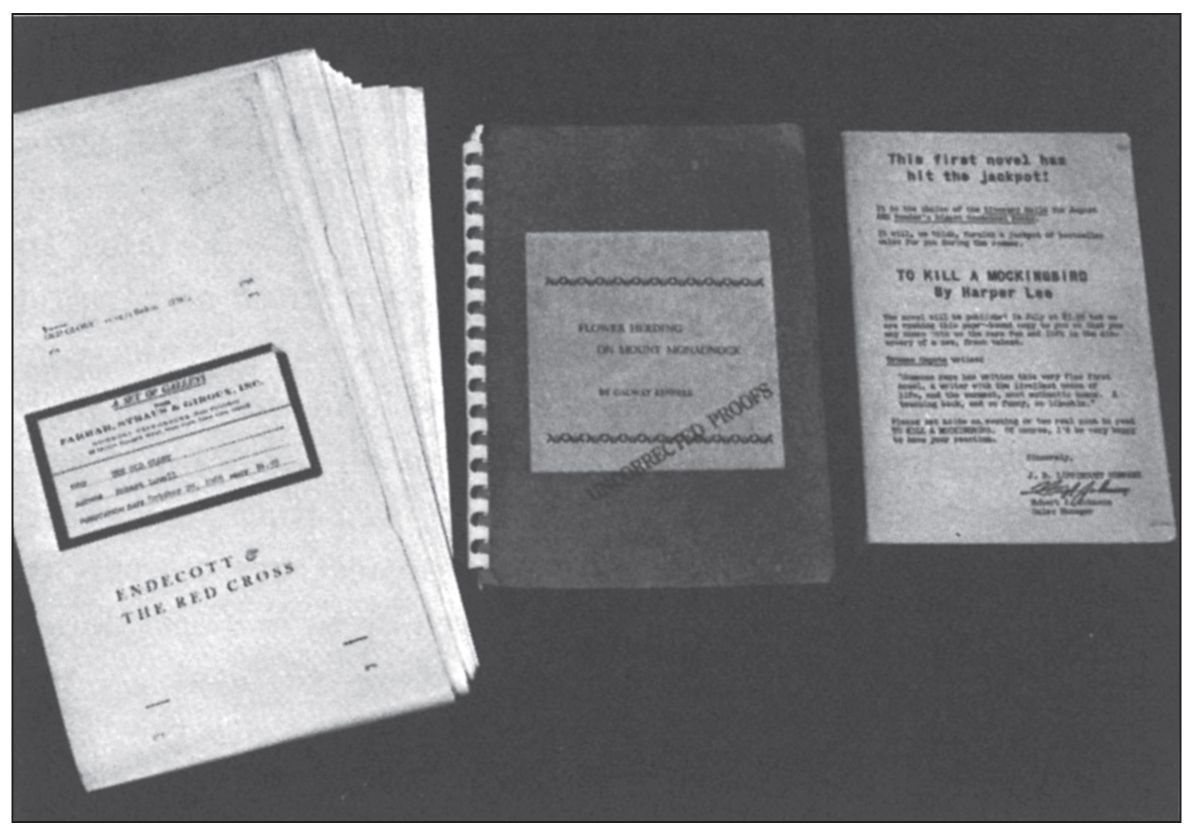

When the first proofs are received, the publisher will send a set to a company that produces bound galleys. These are usually made from the original uncorrected, unproofed typesetting. They are printed by offset onto somewhat shorter sheets (although generally still taller than the finished book), still on a cheap variety of paper, and usually bound in stiff wrappers, sometimes glued and sometimes fastened by spiral plastic bands. The resulting “books” are intended primarily for publicity purposes. Some are sent as advance copies to important reviewers, some are circulated within the publishing house to the sales force, some are sent out for comment or quotes in advance of publication, some may be submitted to book clubs, such as the Book-of-the-Month Club or the Literary Guild, for consideration as a selection. The number of copies of such bound galleys may vary from half a dozen for a volume of poetry or a long, expensive deluxe book all the way up to as many as seventy-five or a hundred copies of a book that will receive widespread publicity.

Occasionally a firm will have a book that warrants the expense of producing a special “Advance Issue.” This is usually printed on something better than proof paper, often the same paper that will be used in the final format of the book, and has a better quality cover than the normal set of bound galleys—possibly even the actual dust jacket, glued around the book. Or the advance issue may have a printed wrapper bearing a message from the publisher or some famous author explaining why the book is felt to be of particular interest or importance. These copies are usually produced from the final text, or as close to the final state of the text as is possible at the time. They generally resemble the finished book in size and general appearance except for the paper binding. Such a book is usually identified on the cover by the words “Advance Reading Copy” or some similar designation. These are usually produced in fairly large quantities, at least five hundred—as was the case with Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood—or even several thousand copies, particularly if the book is to be publicized at the American Booksellers Association annual convention. Advance copies are usually distributed rather generously at the ABA conventions in the hope of securing large advance orders from retail bookstores. They are of course eagerly sought after by collectors, since they are obviously the earliest form of the book to be released to the public. In some cases they may contain material that does not appear in the final issued version.

When all corrections have been made, the columns of type are separated into page lengths by the compositor. Then (assuming the book is being printed by offset) such things as running heads, chapter headings, page numbers, etc., are stripped in (i.e., actually pasted onto the appropriate page), and all other material is added—such front and back matter as title page, foreword, dedication, table of contents, index, or whatever nontextual material was not actually set in the original galleys. When this work has been okayed by the publisher, the printer photographs the paste-up, strips the resulting negatives to a “flat” roughly the same size as the sheet of paper the book is to be printed on, and makes a set of blueprints (much like an architect’s) of the finished flats. These, folded, are known as “blues.” Once again, the publisher gives them one final check to make sure that everything is in its correct place, in sequence, and right side up—especially the front and back matter, which has been added. Then a set of printing plates is made from the approved flats, and actual printing begins.

At this stage it is possible for the publisher to request sets of the folded and gathered sheets—actually finished copies of the printed portions of the book, lacking only the binding. This is not often done nowadays, since the binding process takes a very short time, but it means that the reviewers can be supplied with material a few days earlier. These folded and gathered sheets—known as “f and g’s”—are generally requested only in the case of art books or illustrated books that could not be judged fairly on the basis of the text alone.

The publisher will ideally receive completed books, bound and dust-jacketed, five to six weeks (sometimes less) before the official publication date of the book. This allows time for the books to be shipped to bookstores so that there will be stock on hand when the actual publication date arrives. It also allows time for review copies to be sent out. Formerly, most publishers employed a rubber stamp inside the front covers of review copies to mark them, but today the common practice is to insert a specially printed slip, giving the price and the official publication date, and requesting that two copies of the review be sent to the publisher. Sometimes a glossy photo and a brief biography of the author may also be inserted. In the past, many publishers double-jacketed review copies so that the newspaper or magazine could, if it chose, use one jacket to illustrate the review. These copies are known as advance review copies and are usually distributed rather liberally by major publishing houses as a form of advertising a new book. Collectors naturally prefer these, since in the normal course of events such copies are issued some weeks prior to the regular copies of the book.

Some prepublication forms of literary material: loose galleys of Robert Lowell’s ENDECOTT AND THE RED CROSS; bound galleys of Galway Kinnell’s FLOWER HERDING ON MOUNT MONADNOCK; and a special reading edition of Harper Lee’s TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD. From the author’s collection.

In some cases advance review copies may come to be regarded as extremely desirable first issues, when some vital mistake is discovered after their distribution and corrected before the rest of the books are sent out. There are several instances of this. Even as I write, it has been discovered that such was the case with Bernard Malamud’s Dubin’s Lives. But perhaps the most notable instance, if only for the convoluted sequence of events and the variant copies that it gave rise to, is Marianne Moore’s Collected Poems. This book was published in 1950 by Macmillan in New York, with a corresponding edition in England by Faber & Faber. At that time it was common for publishers to have the entire printing for a joint edition done in Europe, with either the completed books shipped here, or sometimes the sheets alone, which were then bound and jacketed in the United States. In this particular case, the complete book was printed and bound in England in two editions, one with a Macmillan title page and the Macmillan imprint on the spine, and the other with a Faber title page and the Faber imprint on the spine. Since Miss Moore was an American, it was agreed that the American edition would be released first to protect her copyright, the British edition following some three or four weeks later. Accordingly the Macmillan copies were shipped to the United States. Now, a shipment of three or four thousand books occupies a very large amount of space, and on any bulk shipment comprising identical items in quantity, the standard practice of the U.S. Customs is to release all but one case to the consignee, who is expected to hold all the merchandise, no matter what it is, until the one retained case has been examined by the customs agents and a final clearance given. Not expecting any problem, Macmillan sent out review copies, some sixty-five in all, before word came from Customs that the books were not admissible because they lacked a printed copyright notice on the verso of the title page. If the books were released thus, Miss Moore would lose her copyright. Obviously this could not be allowed to happen, and all the books had to be shipped back to England—all, that is, but the sixty-five review copies, which were at this point irretrievable. Macmillan then hurriedly proceeded with production of a wholly American-printed edition, but this could not be readied in time for issuance before the Faber edition was released in England. Thus the first edition situation is as follows: a total of sixty-five copies, bearing a Macmillan title page and Macmillan imprint on the spine, but no copyright notice; next, a British edition, with Faber on the spine and a Faber title page; then the American-printed American edition (in blue cloth instead of the original orange), with Macmillan on the spine, a Macmillan title page, and bearing a copyright notice. Just to add to the confusion, when the copyright-less batch of Macmillan copies arrived back in England, rather than sacrifice the entire lot Faber sliced out the title page and tipped in a new one, bearing the Faber imprint. This created bastard copies with a Faber title page but a Macmillan imprint on the spine, and these were issued after Faber had sold out its initial supply. So there are four variants of the first edition of Marianne Moore’s Collected Poems—and the sixty-five advance review copies sent out by Macmillan clearly enjoy priority over all the others.

Most modern books go through all of the production stages described above, although occasionally one of the steps will be bypassed. Material from each stage, however, is of interest to most collectors, especially “in-depth” collectors. The big trick is to get hold of such material. Review copies for most books turn up in the market fairly frequently, for regular reviewers usually supplement their income by selling unwanted books. Advance reading copies also turn up fairly often, for the same reason, and bound galleys sent out as review copies also come into the market occasionally. But the other formats are never released by publishers and, as indicated, often exist in only a very few copies. To recapitulate, here is a list of the possible states of a book, arranged chronologically:

- 1 Author’s manuscript

- 2 Photocopies of the manuscript, prepared for house use. Either one of these or the author’s original will serve as the “setting copy,” with corrections thereon.

- *3 Long galleys (usually about three sets), including the set with the author’s corrections

- *4 Bound galleys

- *5 Advance reading copies (usually in special wrappers)

- 6 “Blues”

- 7 Sets of folded and gathered but unbound sheets

- *8 Advance review copies of the completed book

- *9 Completed book as issued

The starred items are the ones sometimes or often available in the market. The others are very rarely seen outside the publishing house. But, of course, whatever exists will be sought and valued by collectors interested in the work of that particular author.