CHAPTER FOURTEEN

INVESTMENT

Most dealers have, at best, ambiguous feelings about customers who are frankly collecting for investment, and while no dealer in his right mind will refuse to sell a book to a customer for this reason alone, dealers usually prefer to place their better books with customers who are collecting primarily for the love of the sport. Realistically, of course, no collector is ever completely unconcerned about the value of his books. One of the many satisfactions in owning a collection is the pleasure of watching a book you have purchased at a nominal price, perhaps even at publication price, start on an upward spiral.

In the past couple of years there has been a considerable amount of discussion in newspapers and national magazines about the investment potential of rare books. Part of the reason for their attractiveness is the fact that several other popular inflation hedges have performed erratically recently, or moved beyond the reach of the average investor. Gold coins, after a boom, stayed more or less level for several years. Impressionist and other modern paintings (which first took the lead in price rises) are now far beyond the means of all but millionaires. Antique furniture, while a good potential investment, presents a massive storage problem. So attention has turned to the field of rare books, where prices are still moderate, supplies available, and storage problems not overly burdensome.

A sure sign of the widespread belief in the attractiveness of rare books as a form of investment is the sudden proliferation of companies purveying what they term “collectors’ editions.” These are supposedly deluxe limited editions, sold at fancy prices by direct mail and by means of heavy advertising in mass magazines. The advertising is not at all hesitant to tout the investment potential of these books, implying that they are bound to increase in value. All the more reason to bear in mind that several factors must obtain for this to occur. First of all, the book has to be truly scarce, if not rare. (These two terms are vague at best, and are quite often used interchangeably in dealers’ catalogs. However, most collectors and many dealers will agree that “scarce” means that a book will be difficult to find immediately or even soon, but will, in all probability, eventually turn up within a reasonable period of time. A truly “rare” book may not be seen for years, perhaps not for decades.) To be scarce or rare, the initial number of copies in existence must be relatively small. “Relatively small” can mean as many as a thousand copies, but certainly no more than that, and probably far fewer. Secondly, it should have the advantage of being either a first edition or, at the very least, an edition that offers something that no other edition can boast—perhaps the signature of the author, or illustrations by a well-known artist, perhaps original etchings or lithographs bound in or an extraordinarily fine binding. The firms offering “collectors’ editions” currently meet very few, if any, of these requirements. One firm does advertise that all of its books are first editions—in fact, uses the words “first edition” in the club’s name. Much of the time it is true that their edition is a legitimate first, but in several documented cases their editions were in fact issued later than the corresponding trade edition. Ultimately, when bibliographies of the various authors involved are compiled, this lack of priority will be spelled out. As a result, the book is scarcely likely to command any kind of premium.

The prospectuses and advertising copy of these various clubs are shrewdly calculated to trap the unwary. While nothing that they state is actually untrue, a lot of information that is crucial and relevant is carefully omitted. When the most prominent of these companies started its series, an advertisement listed the authors whose new books the firm would publish and then elaborated in considerable detail the high prices that certain titles by those authors were now bringing. For example, W. H. Auden’s Sonnet was quoted as being worth anywhere from $400 to $600, and William Faulkner’s Marble Faun $1,700. Both of these price indications were correct (perhaps even underestimated), but it takes very little research to show how little they have to do with the prospective value of books issued by the club. Auden’s Sonnet was privately issued in 1934, early in the poet’s career, in an edition of only twenty-two copies. Faulkner’s Marble Faun was virtually worthless for nearly forty years after its publication in 1924, during which time the never very large number of copies in the initial printing became very small indeed. The number of copies actually issued by the club of Auden’s Collected Poems and the Selected Letters of William Faulkner (two of the authors singled out as prime examples of good investment possibilities) exceeded 40,000—more, in fact, than were published in the regular trade editions of the books. Now, it is possible for these books to increase in value—but I wouldn’t wait for it to happen! So, the first trap for an investor to avoid is that of joining a book club that promises him, even by implication, books for investment.

There have been, and still are, many other book clubs devoted to the production of fine books in limited editions, most of which are legitimate and do produce handsome books. The Limited Editions Club has been in existence since 1929, producing, usually, a book every month; but not for investment. Many people join this club for a couple of years and then are distressed to learn that they seldom can get their original investment back when they go to sell the books. Handsome as they are, very few of them have increased very much in value over the years.

Among the most notable of Limited Editions Club books that have appreciated is James Joyce’s Ulysses with six original etchings by Matisse. This edition was originally announced as being signed by both Joyce and Matisse, and Matisse did actually sign the colophon sheets for all 1,500 copies. Joyce, however, signed only slightly more than 250 sheets, ceasing when he realized—on looking at a set of the etchings airmailed to him—that Matisse had not illustrated his work at all but, through a misunderstanding, had illustrated Homer’s Odyssey. So copies bearing both signatures command a far higher premium than those with only Matisse’s signature, although, naturally, any copy of the book, containing as it does six original Matisse etchings, brings a healthy sum. The Limited Editions Club edition of Lysistrata, illustrated by Picasso, also always brings a high price, as do the two Alice books signed by Alice Hargreaves (the original Alice for whom Lewis Carroll wrote the stories) and two or three other titles in the series, mainly those with illustrations by such notable twentieth-century artists as André Derain and Thomas Hart Benton. But such wanted books account for fewer than a dozen titles out of nearly six hundred. It bears out the principle that book club editions, no matter how fine, must have some other important distinction ever to become valuable.

Investing in books as a form of profit making is just as risky as investing in stocks and bonds. Seemingly “safe” authors may fall from grace and favor and never again find popularity among collectors. The classic example, known to every dealer, is that of John Galsworthy, who in the late 1920s and early 1930s was the twentieth-century author to collect. His first book, From the Four Winds, written under the pseudonym of John Sinjohn, was eagerly sought after and sold readily for $500 or $600 in 1933, when that amount of money represented a staggering figure. (To gain perspective on this, remember that a married man could raise a family, own his home and perhaps even an automobile, on a salary of $45 a week. The best cut of sirloin steak was 25¢ a pound.) After World War II, Galsworthy fell from popularity and has never recovered with either collectors or readers. Even the success of the television version of The Forsyte Saga a few years ago failed to create any demand for his work other than a brief flurry of interest in that one sequence of novels. Nowadays, you can buy From the Four Winds for well under $100, and the complete combined The Forsyte Saga for not much more, even in the deluxe edition. The other titles cannot be given away. So anyone who invested in Galsworthy has taken a terrific beating.

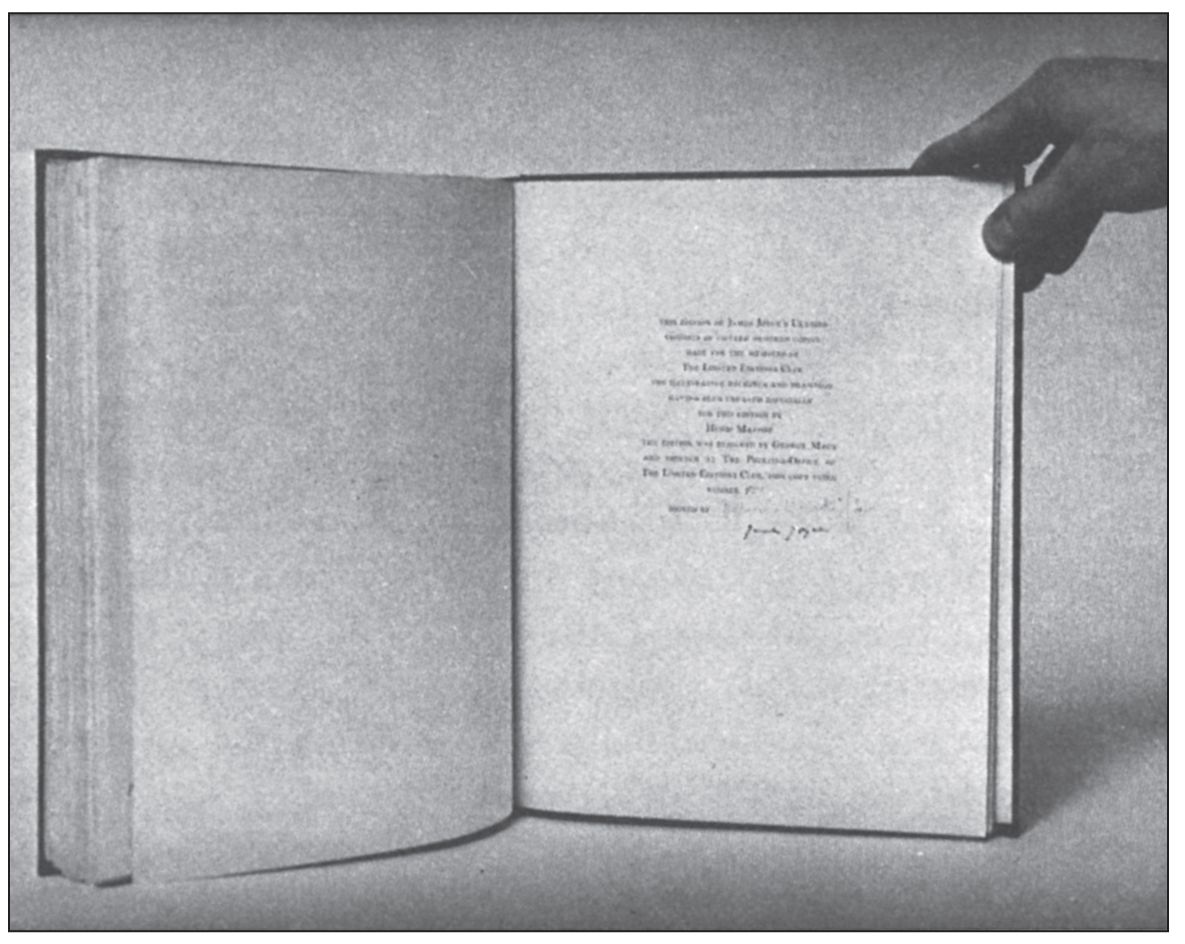

Colophon page of one of the few copies of the Limited Edition Club’s edition of James Joyce’s ULYSSES, illustrated by Henri Matisse, that were signed by both Joyce and Matisse. From the author’s collection.

Nor is that an isolated example. Forty or fifty years ago, the popular authors to collect were H. L. Mencken, James Branch Cabell, A. E. Coppard, Joseph Hergesheimer, Carl Van Vechten, Willa Cather, Robinson Jeffers, Eugene O’Neill, and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Mencken and Cabell slumped badly. Cabell today commands only a very limited audience, and his books sell at modest prices. Mencken has started a comeback, but there is absolutely no interest whatever in Hergesheimer or Coppard, and only a modicum in the works of Van Vechten. Millay, Cather, O’Neill, and Jeffers, of course, are still widely collected. But the same precipitous decline may—and undoubtedly will—strike some of today’s top favorites during the next two decades. It would be patently foolish at this point to try to predict which ones they will be. But certainly very few of the much sought after novelists of the present generation will remain in great demand at such inflated prices as are now current.

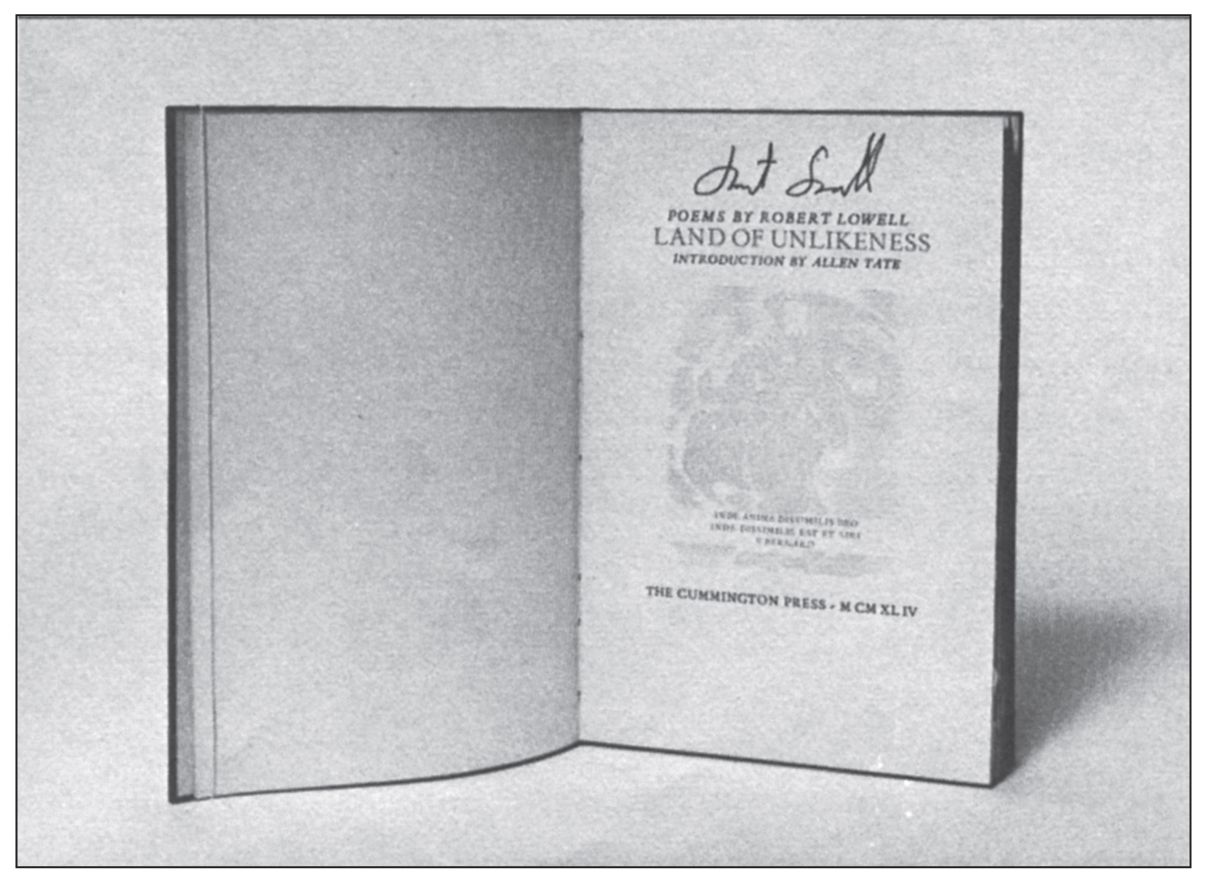

Title page of Robert Lowell’s first book, signed by him. From the author’s collection.

My belief, based on nearly forty years of experience and observation, is that poets fare better in the long run, for many reasons. For one thing, they arrive much more slowly at peaks of eminence and, in the nature of things, also decline —if they ever do—far more slowly than popular novelists. Another important factor is that the number of copies printed of a book of poetry is extremely small in most cases, especially when compared with the quantity printed of a popular novel. A book of poetry may well have only five hundred or a thousand copies in its first printing (if, indeed, it ever reaches a second). For example, Robert Lowell’s first book, The Land of Unlikeness, was published in 1944 in an edition of 226 copies, at $2 each. Four years earlier, Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls appeared in an edition of 75,000 copies. Hemingway’s reputation was well established by that time and copies of his book were readily bought up by collectors. Very few people had ever heard of an unknown poet named R. T. S. Lowell, and only a small number of people bought the book. Those who did buy it were mostly fans of the Cummington Press, which printed it, and they purchased it as an example of fine printing. Some three or four decades later, the price of the Hemingway book has done little more than keep pace with inflation, not because of any decline in Hemingway’s popularity with collectors but simply because of the enormous number of copies available. On the other hand, Lowell’s book is now recognized as one of the key books in any collection of postwar American poetry, and easily fetches four figures when a copy comes on the market. Lowell’s second book, Lord Weary’s Castle, was published by a commercial firm, Harcourt, Brace and Co., and earned him his Pulitzer Prize. While the firm will not disclose the actual number of copies printed, it was almost certainly fewer than five thousand—far, far fewer than that of a Hemingway novel. Today, of course, a copy will cost far more than a copy of Hemingway’s Bell. This parallel can be drawn all along the line between poetry and fiction. Among living novelists in the late 1970s, John Updike is far and away the most collected fiction writer. His books are produced in enormous quantities, and most also appear in book club editions. Updike novels usually have large initial printings—up to fifty thousand copies—and sometimes go into later printings. His signed, limited editions (issued concurrently with the regular trade edition) are always oversold before publication. On the other hand, the books of the poet Howard Nemerov, a recent National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize winner, are produced in relatively small editions and often remain available for several years in the first printing (most never go into later printings at all). In all probability, decades hence the later novels of Updike will, like Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls, be available at reasonable prices despite a continued interest in Updike. The volumes of Nemerov’s poetry, all other factors being equal, should rise appreciably over the years simply because there are so few of them.

There are, of course, as with everything, exceptions to this generalization. If a poet such as Carl Sandburg, Marianne Moore, or Allen Ginsberg becomes a public figure (usually, it must be admitted, because of his or her picturesque personality), large editions of his or her work will be printed, though still not nearly as big as those of popular novels. Thus, Marianne Moore’s last few volumes will probably never be high-priced items since there are sufficient quantities available to satisfy any and all collectors. The same applies to the later books of Ginsberg, produced in editions of thousands of copies. But Ginsberg’s first two books, the aforementioned mimeographed Siesta in Xbalba and Howl, a watershed volume in the history of American poetry, climb steadily in value. It is fairly safe to say that they will always command a large price, since, whatever one may think of Ginsberg’s oeuvre overall, his impact on the course of modern poetry has been (in my opinion) greater than that of any other single poet in this century. His books will always have a unique place in literary history—and among collectors.

Many collectors do not have a realistic idea of how much a dealer can or will pay for books. This is often a source of disappointment and sometimes even anger. Especially in the case of modern books, which are often in fairly adequate supply, the would-be seller may be startled to find that he cannot get as much as he paid in the first place, even if he has kept the book for a considerable time, unless for some reason the price for that particular volume has increased significantly. With very few exceptions, no dealer can or will pay more than half of what his ultimate retail selling price will be, and many dealers pay even less than this. Fifty percent is the absolute top price that should be expected. Thus, if the collector has bought novels of an established author such as Norman Mailer or John Updike or Colin Wilson, particularly the middle and later titles of such authors, he should expect to experience difficulty in breaking even. These later titles were all issued in extremely large quantities and are therefore not difficult to find. When such books as these are offered, most dealers will be only mildly interested. Chances are they have at least one copy in stock and perhaps many more, with no prospects of immediate sale. So an offer below the original purchase price can be quite honest and is in no way intended to cheat the owner. In fact, by offering to buy the books at all, the dealer may be doing the seller a favor. There is one way for the seller in such a predicament to realize somewhat more on his investment, and that is by taking other books in trade rather than cash. Most dealers will allow a higher price if it is in trade for other merchandise, the usual offer being approximately another 15 to 20 percent above the cash price.

If the collector has bought books after the particular author has come into widespread collector popularity, he has probably paid premiums for some of them, making his chance of breaking even on resale even less. Once again, the rule of thumb of one-half the dealer’s prospective retail price applies. Even with today’s rapid increases, it takes a long time for a book to double in price—necessary if the owner is to get back his original investment—or to increase beyond that point—necessary if he is to make a profit. As always, there are exceptions, but as a general rule, little or no profit can be expected on books held for less than a decade. As has been repeatedly said, book collecting should be done for the fun and love of it, not primarily for profit.

Still another factor playing a part in determining prices is one that many people fail to take into consideration. Yet it is probably the most important one of all. Condition has been stressed in other chapters of this book. Modern books, and particularly books published in the last thirty years, are, with very few exceptions, not difficult to find in fine condition and usually with presentable dust jackets. Therefore, many dealers refuse to buy copies without dust jackets, and few dealers, if any, will buy worn copies of books published since World War II. Many beginning collectors hear about phenomenal prices, especially after an important auction, or read high prices in catalogs, but fail to comprehend that these high prices are based very largely on the fact that the book’s condition is splendid. They think that their dog-eared copy should bring just as much and cannot understand why the dealer either offers very little or refuses to buy. The importance of condition in a book is much the same as condition in a used automobile. A used Ford in fine running condition is worth far more than a smashed-up Cadillac beyond repair.