Aperture, shutter speed and ISO—these are exposure’s magic three. They work together to yield proper exposure and are known as the exposure triangle.

What is proper exposure? Overexposed photos are too bright and washed out, resulting in a loss of detail. Underexposed photos are too dark. A well-exposed photo is somewhere in between the two, where the tones are balanced and the important details are visible. The interpretation of proper exposure is somewhat subjective, and sometimes incorrect exposure may yield a desired creative result. A proper exposure can be achieved by manipulation of aperture, shutter speed and ISO in conjunction with a particular metering mode, which we’ll discuss soon. Let’s first talk about each part of the exposure triangle.

That hole in your lens is called an aperture. It can be set to different sizes, and that’s typically anywhere from f/1.4 to f/22. The bigger and wider apertures let in more light, while the smaller sizes let in less. So, if there is not much available light in your scene, a wider aperture can let in enough light for proper exposure. If the scene is very bright, a smaller aperture can let in less light and prevent overexposure. Aperture is measured by f-numbers (also called f-stops). Take note that the smaller the f-number, the larger the aperture will be, while the larger the f-number, the smaller the aperture will be. The trick to remembering this is to think backwards.

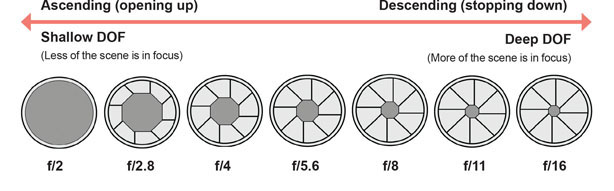

This figure shows the relative size of common aperture settings that are one full stop apart. The smaller the f-number, the larger the aperture will be, while the larger the f-number, the smaller the aperture will be. Keep in mind that today’s DSLRs operate with fractional stops (fractions of a full stop), so they will have more aperture sizes than are shown here.

When you descend from one aperture opening to the next, the f-number increases while the aperture gets smaller and cuts the amount of light going through the lens in half (e.g., moving from f/5.6 to f/8). This is called “stopping down.”

When you ascend from one aperture opening to the next, the f-number decreases while the aperture gets bigger and doubles the amount of light going through the lens (e.g.: moving from f/11 to f/8). This is called opening up. When you set your lens to its widest aperture, it’s called “wide open.”

Each halving or doubling of the light represents one full stop. The same halving and doubling concept also applies to shutter speed and ISO. This relationship is an important aspect of the exposure triangle, as we shall soon see.

Don’t worry if your head is now spinning after wading through those explanations. Mine did too, the first time I tried to understand how aperture works. I would start to understand what I was reading, only to have that understanding vanish as I got deeper into the information. That’s normal, so keep rereading until it sinks in. You will find that as you apply and practice the technical tips given throughout this book, concepts like these will eventually become as familiar as the back of your hand. You may also be asking why you need to understand how f-numbers work. It is because you can control aperture size to create a variety of interesting and creative effects, which leads me to my next point.

The size of the aperture not only controls the amount of light let into the lens, but it also controls depth of field (DOF). DOF is the portion of your photograph that is in focus. Manipulating DOF can yield some very creative photos. You will notice that outside of your scene’s DOF, objects become blurry. There are two creative uses of DOF: shallow DOF and deep DOF.

Important note on fractional stops: Most modern DSLRs use 1⁄3 of a stop increments by default, and give you the option of 1⁄2 of a stop increments. Keep this in mind as you calculate a full stop. My DSLR gives both 1⁄3 and 1⁄2 of a stop options, and I choose to operate it in 1⁄3 of a stop increments. As I flip the dial, I know I have reached a full stop with every third click.

Shallow DOF is often used for portraits because it allows you to keep your subject clear and in focus while blurring the background. The blur softens and simplifies the background and isolates the subject, making her front and center. To achieve shallow DOF, make the aperture big. Depending on your lens, you can try anywhere from f/1.4 to f/5.6. Remember that a bigger aperture is represented by a smaller f-number.

Deep DOF is often preferred for landscape photography because it allows the photographer to create shots that are in focus throughout. To achieve deep DOF, set your aperture to a smaller size (f/16 or smaller). Remember that a smaller aperture has a bigger f-number. Tip: Some DSLRs can stop down to f/32 or smaller. Be aware that something called “diffraction” can occur with these very tiny apertures. Diffraction actually causes blur.

Besides aperture size, two other factors affect DOF. They are distance from your subject and focal length.

Distance from your subject: When you get closer to your subject, even if you have selected a smaller aperture (greater f-number), the DOF will decrease, meaning the area that is in focus will become smaller. If you move farther away from your subject, the DOF will become greater.

Focal length: Focal length is the length of your lens. A prime lens has a fixed focal length. Zoom lenses have a range of focal lengths. You zoom in to make the focal length longer, and zoom out to make it shorter. Shorter focal lengths will make the background clearer, while longer focal lengths will do just the opposite and make the background blurry. So if you want the background to be blurry, zoom in on your subject. If you want the background to be clearer, do the opposite and zoom out.

This landscape photo is an example of deep DOF, where the scene is in focus from front to back. My goal was to create a wide-angle shot where the meandering path was in focus throughout. I snapped this photo using my 15–85mm f/3.5–5.6 lens with a small aperture setting of f/22 (for clarity from front to back) and a focal length of 15mm, which captures a nice wide-angle view of the scene.

This photograph is an example of shallow DOF, where the tulips in the foreground are crisp and clear, while the elements in the background are indistinct and blurred. I took this shot with my 15–85mm f/3.5–5.6 zoom lens, with an aperture setting of f/5.6 and a focal length of 40mm. I was relatively close to the tulips when I took the shot, which blurs the background more than if I were farther away.

Use your lens’s sharpest aperture when the important elements in your scene are on the same plane; doing so will make these elements look tack-sharp. This photo was enhanced in Photoshop with an MCP Action.

Most lenses are at their sharpest at either f/8 or f/11. This is called the “sweet spot” of the lens. If you want to discover your lens’s sweet spot, a general rule of thumb is to calculate two full stops down from wide open. If your DSLR operates with fractional stops, you will need to keep that in mind as you calculate. So if your lens’s widest aperture is f/2.8, its sweet spot aperture will be f/5.6. Use the sharpest aperture when the important elements in the scene are generally at the same focal distance (if they are on the same plane). This ensures that all the elements will be tack-sharp, as long as there is no camera shake, of course. Using your lens’s sharpest aperture for scenes with depth, especially landscape shots with depth, will not be effective; instead use a smaller aperture (f/11–f/22) for decent overall sharpness.

Later on in the book I will provide you with some photo scenarios and the best aperture sizes to use with those scenarios.

Shutter speed is the length of time that the shutter of your camera stays open when you are making a picture, allowing light to hit your camera’s image sensor. It’s also known as exposure time.

Faster shutter speeds keep the shutter open for a shorter amount of time and let in less light, while slower shutter speeds keep the shutter open for a longer amount of time and let in more light. Bright scenes call for faster shutter speeds; low-light scenes call for slower shutter speeds and often a tripod to prevent blur caused by camera shake.

Faster shutter speeds freeze motion. They come in handy for capturing crisp, clear sports shots; shooting portraits of a wiggly baby; capturing a splashing wave mid-air and seeing each water droplet and rivulet; or capturing every detail of a ballerina leaping.

Slower shutter speeds capture motion progression that is characterized by blur (also known as implying motion). They are used to create those smooth, dreamy, cotton-candy effects in waterfall shots; to capture the motion of a field of wildflowers blowing in the wind; to record the motion progression of people moving in an otherwise still scene; and for a special technique called panning, which we get into later. These are just a few possibilities. Note: Slower shutter speed shots, except for panning, require the use of a tripod to prevent blur caused by handheld camera shake.

Shutter speed is a lot easier to understand than aperture. It’s measured in fractions of a second. If the speed is less than a second long, it will be expressed as a fraction; an example is 1⁄1000 of a second.

Here is a simple trick for decoding shutter speeds that are expressed as fractions. The bigger the number in the denominator of the fraction, the faster the shutter speed will be. So 1⁄1000 is a much faster shutter speed than 1⁄125.

Which shutter speeds are considered slow? Which are fast? Refer to the illustration of standard shutter speeds to help answer those questions. Later on in the book I will provide you with information on photo scenarios and the best shutter speeds to use with those scenarios. We’ll also talk about at what point you need to use a tripod, as opposed to taking the shot handheld. Note: Many DSLRs have a Bulb shutter speed setting. Bulb allows you to keep the shutter open for as long as the shutter release is depressed. It’s often used for photographing fireworks.

When you increase shutter speed by one full stop, say 1⁄125 to 1⁄250, you halve the amount of light that hits the image sensor. When you decrease shutter speed by one full stop, say 1⁄60 to 1⁄30, you double the amount of light that hits the image sensor. Note: Remember that modern DSLRs operate with fractional stops. This applies to shutter speed as well as aperture.

I zoomed in and froze the motion of this wave with a very fast shutter speed of 1⁄1000 of a second. I am mesmerized by the reflections of the blue sky and clouds on the water. You can even see them in the puddles.

I used my 100mm f/2.8 macro lens and a shutter speed of 1⁄4 sec. to capture the motion progression of my friend knitting. Because the shutter speed was too slow for a handheld shot, I used my trusty tripod.

Let’s talk about ISO (International Organization for Standardization). ISO settings allow you to control your image sensor’s sensitivity to light, and thus help you achieve proper exposure. In the olden days (ahem!), you could buy a role of film for your camera labeled with a certain ISO speed. I remember choosing film for my little Kodak 110 camera at the pharmacy: 100 for bright light outdoors and faster 400 film for the lower-light situations, oh, and don’t forget the disposable flashcubes! (I loved the way they looked all cotton-candy-like after use.)

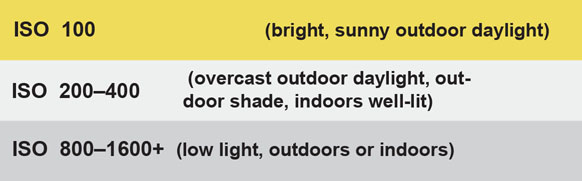

Today’s DSLRs use ISO in the same fashion as their nondigital predecessors, only instead of using specialized film, we can flip our DSLR’s dial to the desired ISO speed any time we wish. The basic rule of thumb is choose a low ISO number for bright light situations, where your image sensor will be less sensitive to the light, and a higher ISO setting for low-light situations, to make your sensor more sensitive to the available light. While it is important to keep the ISO as low as possible to avoid noise and poorer image quality, in low-light situations, without flash or a tripod, raising the ISO may be the only way to get the shot.

I left ISO for last because it’s my least favorite part of the exposure triangle. I have a love/hate relationship with it. I love that it can increase my camera’s sensitivity to light and give me the faster shutter speeds I need for taking handheld shots in low light. Sometimes I hate the unsightly side effect of a high ISO, which is graininess.

You see, higher ISO speeds (usually over 400) produce a noticeable graininess that is not apparent on the tiny LCD, but obvious when you view your photos on a monitor or in print. This is especially true with cropped-frame DSLRs. I struggle to keep ISO as low as possible at all times to avoid the grain. This noise is attractive only if you’re going for an artistic grainy-film look. And yes, I do love it when that’s what I’m aiming for. Otherwise, it is a rather annoying trade-off that can make a stunning capture not so special.

These days, the more-expensive full-frame DSLRs do have nongrainy, faster ISO speeds, but this can come at a cost. Many photographers report a decrease in contrast, color saturation and detail when they use very high ISO speeds.

My guess is that DSLR manufacturers will keep improving over the years where higher ISO side effects are concerned.

Increasing ISO = makes your DSLR more sensitive to the light = which yields a faster shutter speed = which means you’ll be able to take low-light shots handheld and prevent blur from both camera shake and subject movement. Yay! But, wait … the trade-off of a high ISO = graininess in less-expensive DSLRs and reduced image quality in nongrainy full-frame DSLRs.

Choose a low ISO number (slow speed) for bright-light situations, which will make your image sensor less sensitive to the light, and a higher ISO setting (faster speed) for low-light situations, to make your sensor more sensitive to the available light. Most DSLRs start to see graininess at ISO 400, which gets worse as you increase the ISO speed. Full-frame cameras will not see as much grain with faster ISO speeds.

Of course you don’t want to miss important shots, so crank up the ISO if you need to. You can always convert the photos to black and white and embrace this effect, which creatively mimics film grain. Another trick I often use to cover up the grain is to add a subtle texture layer using Adobe Photoshop® Creative Suite® or Adobe Photoshop® Elements®. Or you can try performing noise reduction in Photoshop (CS or Elements). Topaz Labs offers a noise reduction plugin called Topaz DeNoise® made especially for Photoshop and Lightroom. This type of software allows you to perform noise reduction “surgery” on those shots where you just couldn’t avoid the high ISO. Noise reduction software applications can be pretty amazing, but often have a loss in detail, so it’s best to keep the ISO as low as possible in the first place. Here are some basic things to remember.

From this point on, I will give you what is called EXIF data, which stands for Exchangeable Image File Format, for most of the DSLR photographs in this book. I will include the lens type, focal length (the length of your lens, expressed in millimeters), ISO and aperture and shutter speed settings, as in this example: 15–85mm f/3.5–5.6 lens at 15mm, ISO 200, f/3.5 for 1⁄320 sec. Please note that all of my DSLR photographs in this book were shot with a cropped-frame Canon DSLR with a 1.6 crop factor. This will affect the way you interpret the focal length part of the EXIF data, so a 15mm focal length on a cropped-frame DSLR gives the same field of view (which is how much of the scene you can capture) as a 24mm focal length on a full-frame DSLR. I’ll elaborate on this when we talk about lenses in this chapter.

Eventually you will want to move away from shooting with ISO Auto where the camera chooses an ISO setting for you. It doesn’t know that you are trying to keep it low to avoid graininess and reduction in image quality. So be sure to set your ISO manually as soon as you feel ready to.

If photographing a static object in low light with a tripod, set the ISO as low as possible, which will result in minimal photo noise. Because the object is still, you can go with as slow a shutter speed as is necessary to accommodate the low ISO setting. If there is potential for movement with your subject, you can up the ISO some to make for a shorter exposure time, reducing the chances of subject blur.

Most modern DSLRs allow you to set a maximum ISO speed in ISO Auto mode (consult your DSLR instruction manual). If you set the maximum ISO speed to 400, your DSLR won’t ever go above that speed when choosing exposure settings.

I am a huge fan of using natural light for my photography, but I have recently come to see how using a dedicated flash unit (instead of the built-in flash) in lower-light situations can actually look quite natural. I am not a fan of the camera’s built-in flash, as it usually looks anything but natural and can cause red eye. We will be exploring flash possibilities later on, but I did want to emphasize that flash can help you avoid using a high ISO setting. Using a reflector (one of those white, silver or gold discs that come in a variety of sizes) can also help to keep ISO down.

Here it comes …. You took the words right out of my mouth …. Increasing ISO one full stop from say 100 to 200 doubles the sensor’s sensitivity to light, just as decreasing it one full stop from say 400 to 200 halves it. Now we know that all three components of the exposure triangle—aperture, shutter speed and ISO—operate on this same principle. What significance does this have? Now it is time to find out.

Whether a full stop of light comes from aperture, shutter speed or ISO, it has the exact same effect on exposure. There are many different ways you can combine aperture, shutter speed and ISO settings to achieve the same overall exposure; however, each combination will achieve a different creative result. Here you will see two photographs of the same white flowers that I captured with my 50mm f/1.8 prime lens. The first shot was taken with a correct exposure of ISO 100, 1⁄2000 sec. at f/2. In the second shot, which has the same exposure as the first, I changed the aperture from f/2 to f/11 (I stopped down five full stops) and kept the ISO at 100. To maintain the same correct exposure, I needed to slow the shutter speed by five full stops, from 1⁄2000 sec. to 1⁄60 sec. Essentially I did an equal swap of stops. Even though both of these photos have the same exposure, they look very different, don’t they? The photo with an aperture of f/2 has a shallow DOF, while the photo at f/11 has a greater DOF.

Understanding how stops work is essential to manually operating your camera, since you will be the one dialing in settings that yield proper exposure and help you to achieve your creative goals. However, you are never alone in picking your settings because you have a fantastic guide. That guide is called the light meter, which we will discuss next.

I am definitely a fan of and active participant in mobile photography. I view the smartphone as a photographic tool and am constantly amazed by the ways in which mobile photographers use it to create stunning photos and art. Mobile devices do have their limitations. You cannot control shutter speed (the smartphone camera does it for you based on lighting conditions) and the aperture is fixed (depending on the model you have, usually f/2.4 or f/2.8). This can create challenges when it comes to achieving your creative goals; however, there are apps that can help you realize your creative intentions in the post-editing stage (e.g., you can mimic shallow DOF with an app like BlurFX).

Even though both of these photos have the same exposure, they look very different, don’t they? The photo with an aperture of f/2 (left) has a shallow DOF, while the photo at f/11 (right) has a greater DOF.