After the Romans abandoned Britannia, life there changed for the worse. Without the Roman merchant fleet, international trade collapsed, and workshops ground to a halt. Without constant maintenance by the Roman army, roads and aqueducts fell into disrepair. With fewer jobs available, and not much law enforcement, there was more crime. Towns dwindled as people moved back to the countryside, to make a living any way they could.

The most serious threat, though, was from overseas. The Romans had fought vigilantly against pirates, raiders, and invaders from all sides. They had manned a chain of forts and watchtowers along the borders, and kept a fleet of warships nearby. Now, Britain’s coast lay undefended.

Fewer jobs? Less jobs? Which is right? Fewer refers to things counted in whole numbers; less is for things you might have just part of. You wash fewer than three teacups but you drink less than three cups of tea (maybe just two and a half). You go trick-or-treating at fewer than twenty houses (it must be raining!) and bring home less than two bags of loot (the second bag isn’t full).

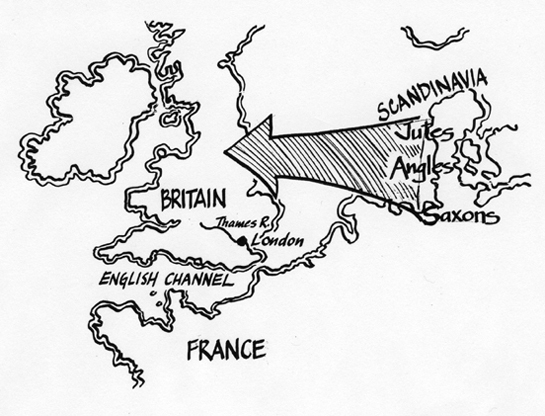

By 440 CE, immigrants from Germanic tribes were beginning to arrive in Britain from northern Europe. Although they were expert seafarers and skilled farmers, they were not as advanced as the Britons had become under the Romans. And they were pagan, worshipping a host of Scandinavian gods of war and nature. In the last years of the Roman occupation, Rome had adopted Christianity, and the new faith had swept through Britain as well.

At first, the Britons and the new arrivals got along fairly peacefully, despite their differences. But then more and more immigrants came flooding in – Angles, Saxons, Jutes, and others – and began spreading through the southeast. The Britons fought many desperate battles, trying to drive the invaders out, but they failed.

Although the borders of Anglo-Saxon Britain were constantly changing, we generally divide it into seven kingdoms: Essex, Wessex, Sussex, Kent, Mercia, Northumbria, and East Anglia. (photo credits 6.2)

By the mid-600s, there were Germanic communities through much of southern and eastern Britain. These grew into little kingdoms that were constantly fighting one another, killing each others’ kings, merging territories and then splitting them up again. We call these people the Anglo-Saxons. They called themselves Angles, and their land was Engla-land. Their Germanic dialects, mixed with Celtic and Latin, became the early form of English we call Old English.

As the Anglo-Saxons took over, many Celts fled back across the sea to Europe, or deeper into the hinterlands of the west and south. The Anglo-Saxons dismissed them as foreigners, Wealas – the root of our word Welsh. (To this day Wales and Cornwall, in the far southwest, are strongholds of Celtic history and language.) The Wealas built tiny chapels and erected stone crosses, and clung to their Christianity. But while their faith remained strong, their memory of Latin slipped away. They repeated the rites and ceremonies of their church, but many of them barely understood the words they were saying.

The years after the fall of Rome are sometimes called the Dark Ages, because so much knowledge was lost, or at least temporarily misplaced. As the Roman Empire disintegrated into small territories, learning and culture took a back seat to rivalry and war. But Europe still had some important centers of scholarship, mostly in religious communities – especially in Rome, where the Catholic Church had grown wealthy and powerful.

In 597, the pope sent a party of monks, led by a learned monk named Augustine, to King Ethelbert of Kent, who was married to a Christian. Augustine persuaded Ethelbert to become Christian, and the religion began to spread through the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The monks built a church and monastery in Ethelbert’s capital city, Canterbury. Augustine became the first Bishop of Canterbury, and later Saint Augustine of Canterbury. (Today, the Archbishop of Canterbury is still the senior clergyman of the Church of England.)

At first, many Anglo-Saxons resisted Christianity fiercely. Monks and nuns were murdered; churches were robbed and burned. But the upper classes were gradually converted by scholars like Augustine, while country folk were won over by humble traveling priests. The pagan gods were set aside. The spring festival of the pagan goddess Eastre became Easter, and the pagan winter festival became the Christ-mass.

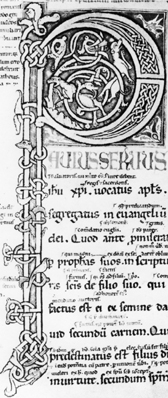

These days, with scanners and photocopiers and faxes, it’s hard to imagine the time and labor and mental concentration needed to reproduce a book by hand. Yet texts were not only copied meticulously, but embellished with illustrated initials and ornamental borders, sometimes with real gold. Notice all the birds and animals lurking in this capital P. And what’s that funny little face in the top left? (photo credits 6.3)

By the end of the 600s, most of England was once again Christian. New churches were built, and adorned with “ivories and jewelled crucifixes, golden and silver candelabra … superbly embroidered vestments, stoles and altar-cloths.” Convents and monasteries sprang up, where ordinary people, as well as monks and nuns, could learn to read and write. The spread of literacy brought back basics of society like record-keeping and accounting and report-writing.

Meanwhile, the Anglo-Saxon kings were still fighting for supremacy. By the late 700s, King Offa of Mercia had more or less taken control of all the kingdoms, by various means (such as beheading the king of East Anglia). Offa called himself Rex Anglorum – Latin for “King of the English.” But when he died in 796, his little empire fell apart. In the early 800s King Egbert of Wessex likewise managed, for a time, to control all the Anglo-Saxon domains, and he is sometimes counted as the first king of England.

But while the Anglo-Saxons continued their rivalry, some Scandinavian tribes to the east, across the sea, had plans of their own. By the late 700s, these bold Norsemen (“north-men,” also called Vikings or Danes) were sailing to Britain and making fast, brutal raids – looting unprotected churches and monasteries of their gold and silver treasures, burning precious manuscripts, smashing tombs, plundering villages, stealing horses, and slaughtering people or seizing them as slaves. “‘From the fury of the Norsemen,’ prayed the peasants in their churches, ‘good Lord, deliver us!’”

The Vikings (Danes) had learned to be the world’s best shipbuilders and sailors, because the rough northern seas were often the only road between their villages. In the 800s and 900s they were not only raiding Britain and northern France, but building their own settlements there. Sometime around the year 1000, their square-sailed, dragon-headed longboats, powered by oarsmen, even traveled as far as North America. (photo credits 6.4)

Before long, the Danes were not only raiding and going home again. They were beginning to take over the country for themselves – just as the Anglo-Saxons had done a few centuries earlier. Year after year the Vikings attacked Britain’s coasts, and year after year they claimed more land as their own. Sometimes the Anglo-Saxons bribed them to go away, with payments called Danegeld (Danes’ gold) – but sooner or later they always came back.

In 851, a fleet of Viking dragon boats moored in the Thames River, and the raiders burned London and Canterbury. In 865 they crossed Northumbria, looting and burning; they seized the city of York, and destroyed the school and library. In 869 they murdered the ruler of East Anglia when he refused to give up Christianity. In 872 the King of Mercia abandoned his crown and fled to Europe.

Now only one Anglo-Saxon dominion stood against the Danes – Wessex. It was ruled by a young king named Alfred.

The religious life offered women a refuge from difficult circumstances. For a few it was also a rare chance for a professional career. Princess Hilda of Northumbria (614-80) became a Christian when she was thirteen, and took her vows as a nun twenty years later. Revered for her wisdom and piety, she founded a church and “double convent” (for both men and women) at Whitby, on a cliff overlooking the sea. Hilda is now a saint.