In the early days of printing, England was still a Catholic country. It’s difficult now to imagine the power that the Church (and the Pope in Rome) had back then, before science improved our lives and helped us understand the world around us. The winters were long and cold, and the typical house was a bare, dark, drafty hut with no heating but a fire. There were few remedies for small miseries like fleas and lice, or aches and pains. Once autumn was past, most people had to survive on whatever food could be dried or salted. When illness or disaster struck, it seemed to come out of nowhere, for no earthly reason.

But churches, abbeys, and cathedrals, with their lofty pillars and soaring spires, lifted people out of all this. Altars glittered with treasures of silver and gold. Massive stonework echoed the music from organs, choirs, and pealing bells. Statues and paintings and stained-glass windows told stories of virtue triumphant. Feasts and pageants and processions broke up the weary work year. There was drama; there was mystery; above all, there was the promise that those who obeyed God’s will during their lifetime would enjoy a glorious eternity.

The church was the center of the community, consoling people for hard times and giving them hope for the future. Overflowing with beauty, glowing with color, it was an earthly promise of heavenly joy. (photo credits 12.1)

The cloak (cappa in Latin) of Saint Martin of Tours, who lived in the 300s, was preserved in a church in a special shrine called the cappella. In time, any small area dedicated to worship became known as a cappella, or chapel. (Cappella is also connected to cobra, the snake that looks as if it’s wearing a hood.)

People depended on priests to tell them what it was God wanted, and to help them atone for any sins they committed, so they could avoid eternal damnation. Most Bibles and other religious books were still in Latin, and church services were conducted in Latin, even though the congregation didn’t understand the language. Indeed, a lot of country priests didn’t know much Latin, especially after so many perished in the Black Death. They just followed the rites and rituals they had been taught.

When the Church approved a book for publication, it decreed, “Imprimatur” – Latin for “Let it be printed.” Today, imprimatur means any official approval – “The new dog park bylaws have the mayor’s imprimatur.”

But the immense wealth and influence of the Church led to problems. One was the conflict between the power of local rulers and the decrees of Church authorities. The Church even decided which books people could read and which were forbidden. Another problem was corruption. While many priests were faithful to their duties, some – especially high-ranking officials – lived in pomp and luxury, and abused their position to fill their pockets. Among other things, they sold indulgences – free pardons – that let rich people “buy forgiveness” for bad behavior.

Back in the 1300s some people had called for reform, saying that the Church’s wealth should be put to better use, and that common people should be able to read the Bible for themselves. But while the Bible had been translated into English, at that time it still had to be copied by hand, and there weren’t enough books to go around.

By the 1500s, though, the protest movement was growing stronger. Those protesting – the “Protestants” – wanted everyone to have access to the Bible. They argued that people should learn to live by their own judgment and conscience, and find salvation through their personal faith – not through favors bought from the Church.

And then along came printing, and the Church no longer controlled the Bible.

In 1525 that first English printing of the New Testament appeared, translated and printed by an English priest named William Tyndale. Church officials opposed Tyndale, knowing that he supported the protest movement. In any case, it was considered heresy (a crime against God) to translate the Bible into English without permission. Tyndale had to print his Bibles in Europe and smuggle them into England, hidden in bales of cloth and other wares. When copies were found, they were seized and tossed into a fire. People who had them were imprisoned, even tortured and burned alive – just for daring to own a Bible.

Tyndale (1494?-1536) was an exceptional scholar, reading Spanish, Italian, German, and Hebrew as well as English, French, Latin, and Greek, but he paid dearly for his beliefs. He went into hiding in Europe and kept on translating, but English authorities tracked him down and arrested him. He was tied to a cross and strangled, and his body was burned.

But the Church soon had something new to worry about. King Henry VIII was desperate for a son who could inherit his throne. (After all, no woman could be trusted to rule England!) He wanted to end his marriage and take a new, younger wife. The Pope refused to let him do it.

In 1534, Henry broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and declared himself head of a new Church of England (the Anglican Church). He closed Catholic monasteries, destroyed shrines, and took over the lands and treasures of the old churches. People who got in Henry’s way found their heads on the chopping-block. Enough of this interference from Rome; the English monarch was now the leader of the English church.

With Rome out of the picture, a number of English-language Bibles were soon on the market. In 1539, a “Great Bible” was published under Henry’s authority. People across England were reading their Bibles and other books about religion, and asking questions, and making up their own minds about God and their faith. Biblical phrases were becoming everyday expressions: “my brother’s keeper,” “the writing on the wall,” “an eye for an eye,” “casting pearls before swine.”

As for Henry VIII, he did finally get a son, but the boy-king died just six years after Henry’s death in 1547. Henry’s older daughter, Mary, who had remained a devout Catholic, became queen and married King Philip of Spain. In the fifty-odd years since Christopher Columbus had found America in 1492, Spanish armies had defeated and ransacked the empires of the Aztecs in Mexico and the Incas farther south. Shiploads of gold, silver, and gems from America had made Spain immensely wealthy, and a powerful ally for England.

In her determination to turn England Catholic again, Queen Mary (1516-1568) persecuted Protestants and had almost three hundred people burned at the stake, including the Archbishop of Canterbury. She’s remembered as Bloody Mary. (photo credits 12.2)

But Mary died after only five years on the throne. Her successor – Henry’s second daughter, Elizabeth – would reign for forty-five years. Although religious conflict continued through much of that time, Elizabeth was firmly Anglican, and England remained Anglican too.

By the time of Elizabeth’s successor, James I, Church authorities felt there were too many different Bibles around; they wanted a new official version. Some fifty scholars worked for several years, revising and retranslating, and depending greatly on William Tyndale’s work a hundred years earlier. Their goal was to produce a Bible that was beautifully written, yet accurate and easy to understand. If a passage described carpentry, they asked carpenters what words to use; if trees were the subject, they consulted gardeners.

Bishops of the Anglican Church disapproved of some of the attitudes expressed in various Bibles. In 1568 they published their own version, the “Bishops’ Bible,” and made it the official Bible of the Anglican Church. (The word “bible” comes from Greek biblos, “scroll” or “book” – also the root of bibliophile, “book-lover.”) Here’s the beginning of the Book of Genesis, opening with a decorative initial: In the beginning God created the heaven and the earth. And the earth was without form, and was void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. In the third line, “the” has been shortened to ye. In the second-last line, “spirit” begins with a long form of s, like an f with one arm missing. (photo credits 12.3)

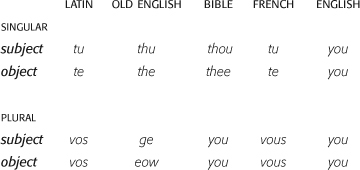

Do you notice something funny about these personal pronouns?

What happened to all those other forms? Why do we always use you?

In many languages, the singular form is considered informal – all right for talking to children or friends, but not for strangers or people senior to you. In Chaucer’s time, the landowner called the peasant “thou” but the peasant respectfully called the land-owner “you.” (The French have a word for this; to call people tu is to tutoyer them.) But as the gap between classes shrank, people began calling everyone “you” to avoid labeling one person as inferior to another.

If the distinction seems odd, consider this: we call children and friends by their first names (“Hey, Chris!”) but we often use last names to show respect for other people (“Hi, Mrs. Jacobs”). Back when rich people had lots of servants, they might call the maid “Alice” but they called the cook “Mrs.” even if she wasn’t married. Servant or not, they had to treat her with respect if they valued their dinner!

Try reading this speech of Ruth’s out loud, listening to the flow of the language. (Ruth’s husband has died, and her mother-in-law has said that Ruth should go back to her own people.)

Intreat me not to leave thee, or to return from following after thee: for whither thou goest, I will go; and where thou lodgest, I will lodge: thy people shall be my people, and thy God my God….