When Elizabeth Tudor was still a toddler, her father, Henry VIII, had her mother’s head cut off. Being Anglican, Elizabeth was lucky not to lose her own head in the years when her Catholic half-sister, Queen Mary, was trying to lead England back to the “true” faith.

When the English weren’t cutting off people’s heads, they were hanging them, especially from the dreaded gallows on Tyburn Hill, near London. Big cranes called derricks, used to hoist cargo onto ships, take their name from a Mr. Derrick, a hangman who “hoisted” convicts there some four hundred years ago.

When Mary died and Elizabeth became queen, she found her new realm in sad shape. England was weak and nearly bankrupt, torn by religious violence, riddled with crime, and threatened by richer and stronger Catholic neighbors, France and Spain.

But Elizabeth was highly intelligent, well educated, and skilled in six languages. She was shrewd and practical, and too sensible to waste her resources on war if she could possibly avoid it. During her long reign, she fended off foreign attacks by dallying with at least fifteen marriage proposals. (Even the King of Spain – Queen Mary’s widower – hoped to marry Elizabeth and recover England as an ally.) Along the way, Elizabeth almost died of smallpox, and ducked endless conspiracies to exploit her, kidnap her, even murder her.

Though she looks calm and confident, Elizabeth I (1533-1603) had to fight hard to keep her throne. One of the gravest dangers was her Catholic, half-French cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots (not to be confused with Elizabeth’s half-sister, Bloody Mary), who kept plotting to take the throne, bring back Catholicism, and make England an ally of France. After years of protecting her troublesome cousin, Elizabeth reluctantly agreed to have Mary, Queen of Scots executed. But after Elizabeth died childless, it was Mary’s son who ascended the English throne as James I – the Anglican who put his name on the King James Bible. (photo credits 13.1)

To defend the country, Elizabeth made sure the army and the great navy her father had begun were rebuilt and modernized. While Europe was suffering terrible religious wars and atrocities, she did her best to create tolerance and cooperation among the English. The resulting peace and security brought a boom in trade and industry. Elizabeth symbolized a prosperous golden age, and her subjects – many of them, at least – adored her. Gloriana, they called her. A few even built their homes in the shape of an E, to show their devotion.

In Elizabeth’s day, some writers felt they had to use classical languages if they wanted their thoughts preserved for eternity (which of course they did). But others deliberately wrote in English, borrowing from Greek and Latin when necessary, to make their own language as rich and versatile as any other. Indeed, some detested the remnants of Latin and Greek, and wanted them rooted out of the English language. One bishop argued that instead of calling something “penetrable” (from Latin penetrare), we should call it “gothroughsome” (from Old English gan-thurh-sum).

Now that they had time and money to spend on themselves, many people turned to entertainment, especially plays. Small companies of actors sprang up. Before that, plays had been staged in any available space, but now real theaters were built, where even poor laborers could stand and watch for just a penny. (Whenever the plague returned, the theaters had to shut down for months or years, until it was over.) By 1592, one of the people working in London theater – acting, writing, perhaps directing – was William Shakespeare.

Shakespeare was a country boy, born in Stratford-on-Avon (avon is a Celtic word for river). We don’t know much about his early life. His father was a leather-worker, and later a town official. Shakespeare seems to have had a reasonably good education, although he didn’t go to university.

Like Chaucer, Shakespeare created lively characters of all types and classes who thought and talked just the way they should. Then he wove them into brilliant tales that felt true to life, no matter how far away or long ago they were set. Shakespeare’s language is quite similar to what we speak today. There are some outdated words, and many references from that age of horse-carts and sailing ships are unfamiliar to us now. But for the most part, this is the English we know.

There were romantic comedies like The Taming of the Shrew, in which Petruchio plans to win the heart of hot-tempered Kate by acting like a lunatic. (To “rail” is to complain angrily.)

Say that she rail, why then I’ll tell her plain

She sings as sweetly as a nightingale.

Say that she frown, I’ll say she looks as clear

As morning roses newly washed with dew….

If she do bid me pack, I’ll give her thanks

As though she bid me stay by her a week.

There were tragedies like King Lear, in which an aged king gives his kingdom and his power to his two evil daughters and then discovers that they both despise him. He is so furious that he can barely talk:

I will have such revenges on you both

That all the world shall – I will do such things –

What they are, yet I know not; but they shall be

The terrors of the earth….

This is thought to be a portrait of Shakespeare (1564-1616), although we can’t be sure. He wrote almost forty plays, and probably acted in most of them. He also wrote beautiful poems, especially love sonnets. His work is so brilliant that some people refuse to believe he wrote it; they insist that the writer must have been someone with a nobler family and a better education. (photo credits 13.2)

Dr. Thomas Bowdler appreciated Shakespeare’s genius, but thought his writing was spoiled by indecent words, scenes, and even plots. In 1807 Bowdler published a new collection of Shakespeare, “improving” the parts he disapproved of. Today, bowdlerizing means rewriting someone else’s work, changing the parts you find unacceptable.

Historical dramas were often designed to please and flatter Queen Elizabeth. (It was always wise to stay on her good side.) In Richard II, Shakespeare tactfully supported Elizabeth’s claim to the throne by giving an earlier king a speech that made him sound like a coward, a liar, and a heartless killer:

Is there a murderer here? No. Yes, I am….

O no! Alas, I rather hate myself

For hateful deeds committed by myself.

I am a villain. Yet I lie, I am not….

With Shakespeare and others doing so much writing, thousands of new words entered the English language. It’s impossible to say how many were actually invented by Shakespeare, but as far as we know, the following (and many others) first appear in his writing: countless, courtship, critical, excellent, frugal, horrid, leapfrog, lonely.

“Striped shorts and a polka-dot T-shirt! He must pick his clothes willy-nilly.” Willy-nilly (“any old way”) comes from “will I, nill I,” meaning “whether I’m willing or not willing.” In The Taming of the Shrew, Petruchio teases Kate that “will you, nill you, I will marry you.” We seem to enjoy expressions that rhyme, or at least repeat sounds. Infants learn to say bowwow, din-din, choo-choo; later we speak of a mishmash, flip-flops, hanky-panky, a hodgepodge, and so on. The parts may not make sense (what’s a mish? what’s panky?) but the sounds are fun.

He also put together wonderful expressions. He had such a fine ear for the perfect way to say something that we quote him more than any other author – often mindlessly, without hearing the literal meaning of the words. But take a fresh look at these Shakespearean phrases, and see how vividly an image can sum up an idea in just a few words:

barefaced

crack of doom

dead as a doornail

eyesore

flesh and blood

foul play

lily-livered

tongue-tied

tower of strength

vanish into thin air

Most of Shakespeare’s plots were not original; he borrowed from real life, ancient myths, and tales from all over Europe. But nobody had told these stories so vividly and powerfully. His works have been translated into innumerable languages. Scholars re-examine them obsessively, writing thousands of books about them, counting how many different words the “Bard of Avon” uses (as many as thirty thousand, compared to just eight thousand in the King James Bible), even counting his commas (138,198). The plays are presented over and over around the world, sometimes as movies and musicals, sometimes with a twist: Julius Caesar as a businessman in a suit and tie, Romeo and Juliet as New York teenagers separated by warring street gangs.

What’s the difference between these two sentences?

1) Alice will go to the zoo if she can.

2) Alice would go to the zoo if she could.

Doesn’t the second sentence tell you that she can’t go?

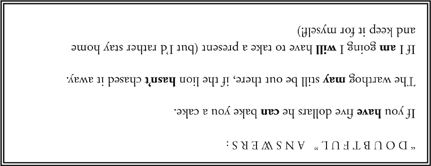

In the past, different “moods” of verbs were used to show whether something was just doubtful (sentence 1), or actually contrary to fact (sentence 2). English has lost many of these distinctions; they were too complicated, and the moods got confused with other forms. But they can still help you make it clear that what you’re describing is not the way things are. The three examples below describe imaginary situations that are contrary to fact. Can you change them so they mean that you simply don’t know whether the situation is true or not?

1) If you had five dollars he could bake you a cake.

2) The warthog might still be out there, if the lion hadn’t chased it away.

3) If I were going I would have to take a present (but I’m staying home and keeping it for myself!)

ANSWERS

In Macbeth, Shakespeare describes three witches as “weird sisters.” The witches foretell Macbeth’s fate (death – though he misunderstands them), and weird comes from the Old English wyrd meaning fate, “what will be.” But over the years, audiences watching these eerie characters have given the word a new meaning: “strange and bizarre.”

Seven years after Shakespeare died, most of his plays were published in a collection called the First Folio. In this First Folio copy of Macbeth, the spelling is not quite like ours. The letters u and v are the same (V is the capital), and the long s (similar to f) replaces our s several times in the opening speech by one of the three weird sisters. (photo credits 13.3)

Yet if Shakespeare had lived before the invention of the printing press, which could turn out hundreds or thousands of scripts, all his plays and poems might easily have been lost forever.