MAY

DATE: TUESDAY, MAY 1, 2012

BANK BALANCE: $105,203.90

CASH RELATIVE TO START OF YEAR (“NET CASH”): -$31,950.42

NEW-CONTRACT VALUE, YEAR-TO-DATE: $704,981

May starts on a Tuesday. Cash reserves are down. Sales? My last-minute surge brought our April total to $161,978. Not what I wanted, but at least better than March.

The production numbers aren’t so good, either. We built projects worth $125,036, with shipments totaling $145,236. I try not to be too discouraged. Considering these statistics on a monthly basis can be misleading. We add a job to the “Built” list on the day it enters the finishing room, and to the “Shipped” list when it goes out the door. A large job can skew the numbers if it’s mostly completed in one month and tallied at the beginning of the next. It’s more meaningful to look at the numbers across a three-month span. Our build for the first quarter, January through March, averaged $207,819 per month, which is better than my goal of $200,000 a month. Shipments averaged $194,418, just short of target. Costs during that period averaged $181,736 per month. We were making a profit, on an accrual basis, of about $12,400 a month, even though our cash position didn’t reflect this. Uncollected balances and the deposits that never showed up in March made our cash balance decline.

As I look at the jobs in our database, it looks like our ship number for May should be much closer to our average. How much will we build? That depends on whether things go well in the shop. Whether workers are moving jobs out the door, or fixing mistakes, or drowning in misquoted, difficult projects. And whether we can keep the shop occupied by adding more work to our queue. I run the calculations for our backlog and it shows four and a half weeks. We’ll be out of work in June. Better get back to selling.

How much time do I spend each day thinking about things? It depends on what else is happening. Aside from my primary job—making sales—on any given day I might have to: review incoming bills; sign outgoing checks; call a customer to find out when they will send us the money they owe us; check bank balances; monitor our credit card accounts; file taxes; photograph a completed table; edit a photo or write content for the Web site; write an ad; change the ads in our AdWords account; evaluate a change in shop operations; move a machine or a worker to a better location; buy new equipment; fix a broken machine; call the landlord about the plumbing, heating, or neighbors; negotiate a new lease; evaluate and purchase health and dental insurance, and general liability, workmen’s compensation, and auto insurance; contest an unemployment compensation claim; do the payroll; decide whether to give a worker a raise; deal with a worker’s request for emergency leave; perform annual reviews; respond to credit checks for my workers; verify employment for former workers; shoot a bird that has found its way into the shop; figure out why a printer stopped working; restart the server; add a user to our network; purchase a new software program; vacuum my office for visitors; get the truck inspected, on and on.

Some of these tasks are interesting. Tinkering with machines is fun. Marketing decisions, especially how to manage the Web site and AdWords, are an intellectual challenge. Some are unpleasant but lead to a satisfying conclusion, like nagging customers for past-due payments. (They’ve always paid me, eventually.) Some are frightening. I can change an employee’s life with my decisions about pay rates and whether to hire and fire. And many are just aggravating: the taxes, insurance purchases, legal issues, and some of the employee interactions. Each layer of government, each enormous and indifferent private bureaucracy, requires its own special knowledge: the right form filled out the correct way and filed at the right time. Learning how to complete one type of tax filing tells you nothing whatsoever about how to fill out the next form. One health insurer presents a quote one way, another in an entirely different way, and both require extensive study to determine the best choice. It’s like stepping back to an old, old world where every tree, every rock, every stream is inhabited by its own resident spirit, and each needs to be mollified in the correct manner. Or very bad things happen.

I didn’t start my company to do any of this. I had no idea, when I decided that I would make furniture in exchange for money, that this was in my future. And the strange universe of administration expands as the company grows. I can push some tasks onto Emma and Pam, our bookkeeper, and we can outsource some payroll functions. The rest is still my responsibility. The company has fifteen employees now, and takes in more than two million dollars annually. If I spread out a year’s worth of administrative tasks evenly, they take about three hours a day.

Please keep in mind, as I tell my story, that the narrative has been extracted from a year’s worth of days that were actually a mix of selling and dealing with this other stuff. Not one single day presented itself neatly arranged, like a book or a movie.

—

WEDNESDAY, MAY 2, brings a bonanza—three large checks, totaling $32,820. Big mood lifter! The first is the deposit for the Maine table, worth $14,918. The second is for $3,300, a preship for a single table that we sold in January. And the last is for $14,602—another preship, for a group of tables going to a local software developer. This cash injection offsets payments totaling $25,304 that I sent out yesterday.

The downer is seeing how much cash we could possibly collect in the future, if, and only if, we finish all jobs and collect all balances. It’s down to just $53,008. Add that to the $127,601 I have, and there are about five and a half weeks before the money is gone. If our output is as low as it was in April, we will run out of cash before we can expect to collect the balances due.

At home that evening, dinner discussion focuses on Peter’s job offer in San Francisco. He’s decided that he wants to commit himself to a whole year of working before starting school. I ask him whether it will be difficult to get permission to defer from MIT, and he tells me that it’s as simple as checking a box on their Web site.

Nancy is strongly opposed. She has a long list of worries that boil down to: young man on his own in a big city, with money. She thinks that he will be lonely. She thinks that he will hate working. Or that he will love working so much that he will skip college entirely. My reaction to all this is—so what? He’s going to grow up one way or another. Take a chance! Go West, young man! If it doesn’t work out, he can always come home.

I have a less noble reason to back his plan: it solves a financial problem for me. When I stopped my salary, I knew that my personal cash would cover Peter’s tuition. Then the cars died. If he defers for a year, I’ll have enough money to buy two decent cars without borrowing, enough to live frugally until the end of the year, and another fourteen months to round up more money. I won’t have to actually write a check to MIT until fall 2013. I’ll be able to reapply for financial aid in the winter of 2013 and show a more pitiful financial picture to the aid officers. I’ll have very little cash on hand, and my income is likely to be much less than one hundred thousand dollars. So the cost of Peter’s next year might come way, way down from the sticker sum of sixty-five thousand a year.

I don’t mention this line of reasoning to my wife. Instead, I point out that my two sisters live in San Francisco, that Peter will always have someone to call if there is trouble, and that he can come home at any time. Her great-grandfather said goodbye to his parents in Minsk and left for America, without cell phone, e-mail, waiting family, or a job. He was brave and his parents let him do it. Are we too weak to let go of our children anymore? He’s going to head out the door one way or another. Why not let him do what he wants? She agrees that he can give it a try for the summer.

—

THE NEXT DAY, Thursday, I design the Eurofurn showroom table. The order arrived in March, but I didn’t want to start until I had seen their factory. I’ll be using a drafting program on my computer to make a drawing. This is how information about an object is normally conveyed from the designer to wherever it is manufactured. The drawing portrays an object, but it actually consists of a bunch of lines and text on screen or paper. It has its own existence, independent of the qualities of the item that is being drawn. If the drawing is unclear, or riddled with errors, production is difficult and inefficient. Drawings look nothing like completed pieces. It takes a great deal of skill and experience to look at them and visualize what the object will look like, and even more to tell how it will work.

In our shop, the sales team does the initial drawing of each table. We modify it as the design is worked out with the customer. When the job is finalized, we send the file to Andy Stahl, our engineer. He will transform our concept into two different formats: one detailed set of drawings for the workers in the shop, and one set of instructions for our CNC machine. His job requires a deep understanding of what happens in the shop, as well as the skills required to convey complex information clearly, both to people and to a machine.

If you studied the drawings that Andy makes for the shop floor guys, you might eventually notice what isn’t there: no indications of what machines to use, no instructions as to how to build the table, or in what order the subassemblies should be built, and nothing at all about how it will be assembled, finished, and shipped. All that knowledge is elsewhere, much of it in the heads and hands of the craftsmen. Our drawings contain about 5 percent of the information required to produce the object they depict.

Andy determines the details of what will be built, but the big decisions have already been made. Dan, Nick, and I do what most of us think of as design—the creation, from nothing, of a new object. How do we do that?

The mental and physical parts of the task are done simultaneously. We think, and we draw. We try to identify what object will function per the customer’s requirements, look good, can be built efficiently in our shop, can be assembled and disassembled with ease, will fit into a shipping container that we can handle, will be durable, and whose cost doesn’t exceed the customer’s budget. And just to make it trickier, the best solution for any single requirement usually means a suboptimal approach to another. Fortunately, we’ve been solving these problems for years and have identified effective strategies for each of them.

I have designed every kind of furniture for home and office and learned that there are many issues beyond durability, looks, and price. Designing a bedroom requires tactful questioning about how it will be used. Designing an individual’s office should include some consideration of how the proposed design will look to colleagues and underlings. Chairs need a great deal of structural knowledge. In contrast, a conference table is pretty simple: a flat surface and something to hold it up. The top should be thirty inches from the floor, with at least twenty-seven inches underneath for legroom. We know that eighteen inches between the perimeter of the top and any vertical structure provides enough knee room, and that we should allocate at least thirty inches of perimeter for each chair, and that the table should be no closer than forty-two inches to the wall or other furniture.

We determine the size of a table by asking the client how much space they have and how many people they want to seat. If their answers contradict each other, we show the biggest table that will fit in the room. Since size is easy to determine, most of our design thinking is about how the table will look, how to build it, and how to integrate the audiovisual equipment.

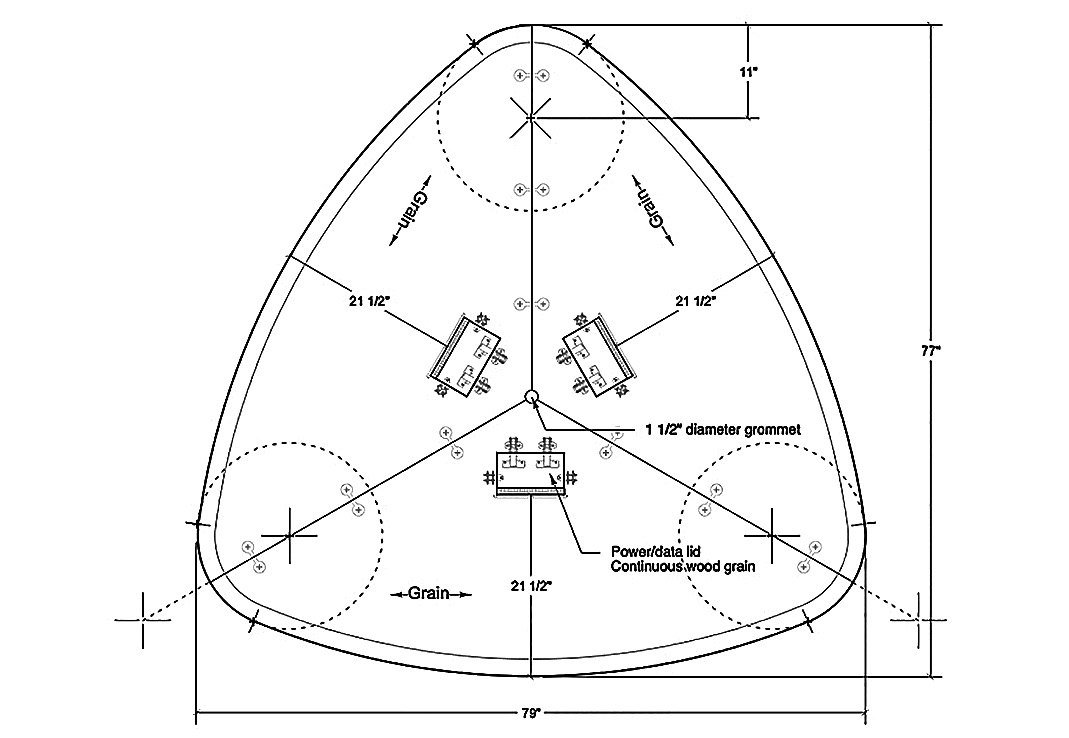

Eurofurn is more sophisticated than our typical customer. They’ve told me what size, shape, woods, and special features that they want. The table will be a modified equilateral triangle, seventy-seven inches long and seventy inches wide, with gently curved sides that become much tighter radii at the corners. Any object based on a triangular geometry presents difficulties, because our materials and equipment are designed for a rectangular world. My machines default to 90-degree cuts. Our wood comes to us in rectangular chunks. And clamps, which we use to hold pieces together while glue dries, don’t work on triangular shapes—as pressure is applied, they slide toward the vertex and then fall. Since clamps are heavy and bulky, this will usually ruin the work.

The top is also too large to cut out of one piece of plywood. It must be made in pieces. I could cut it into two sections, but a single seam running across the triangular top will look arbitrary and clunky. If I make it in three identical pieces, then the seams will reflect the triangular geometry better. Each piece will have its own power/data hatch. In the center, where the three pieces meet, I’ll put a circular hole down into the base. This will allow a wire to be run from a telephone to the floor without going through the hatches, and it will also eliminate the awkward spot where three pointed pieces meet.

I spend some time working out the radii of the two curves on each top edge. We’ll have to bend a piece of solid walnut around these curves without cracking it. We can steam the wood to make it flexible, or we can use several layers of very thin wood and gradually build up the required thickness with multiple glue-ups. I want to avoid either of these techniques, as they are both very slow and extra build hours mean extra cost. I came up with my selling price, $6,523, by estimating how much a production version of this table would cost to build if we have everything worked out. But we don’t have everything worked out, and it will likely take more hours than my estimate suggests.

I complete the drawing of the outline of the top and the seams in a couple of minutes. Then I paste in a drawing of the power/data hatch that I took from an earlier project. Copy and rotate the hatch two more times, add explanatory text and dimension lines, and the drawing is complete (see here).

The next step is to design the base. I know that they don’t want to see any of the wires connecting the power/data units to the building wiring. They’ll want it to look very restrained, very clean, very simple. Very Eurofurn.

I decide that the base will be the same shape as the top: a triangular drum with rounded corners. I’ll make it out of walnut with a stainless-steel accent. But how big should it be? I want to maximize the distance between the edge of the table and the vertical face of the base, to give users as much knee room as possible. People really, really hate it when their feet or knees hit a table base. But if there’s too much overhang, and too little base, the table will be tippy. And more overhang means more top flex. Eurofurn wants this tabletop to be very thin, just one inch thick. In many of Eurofurn’s designs, a thin top is no problem, because there are legs at the corner of the table, but in this case much of the top is unsupported. So I should make the base bigger, to minimize top flex.

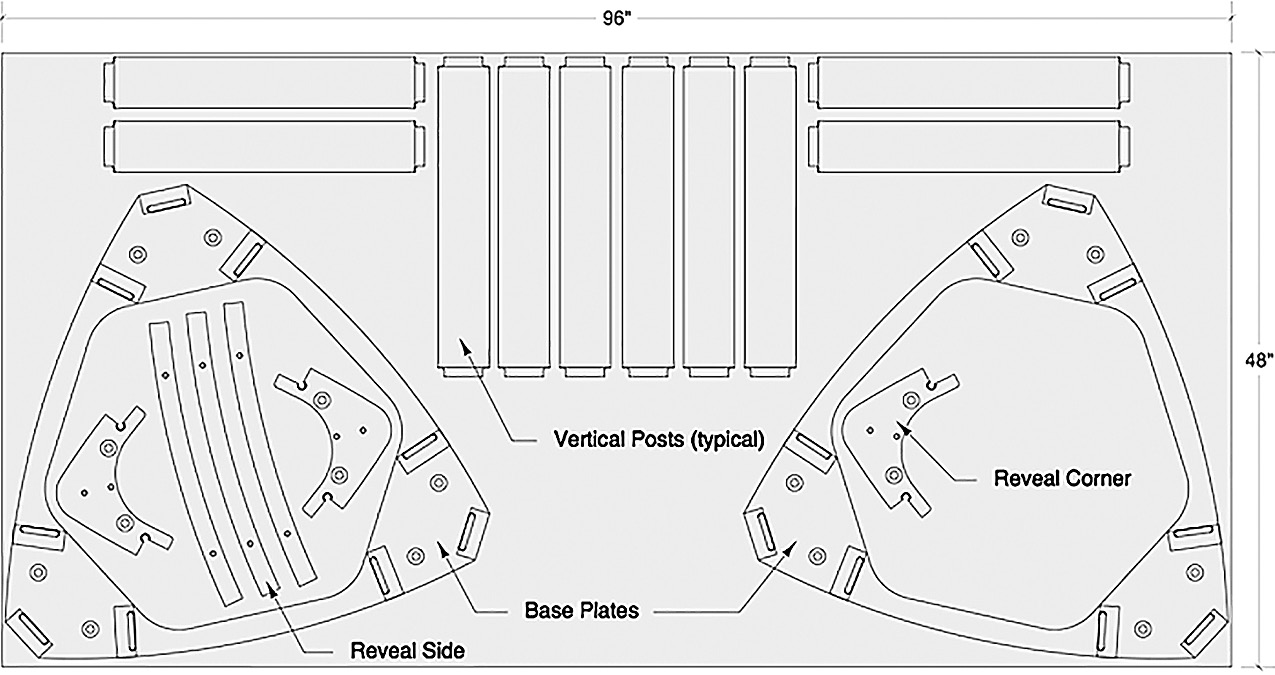

Good reasons to make the base small, good reasons to make it big. I also have one last reason to minimize the size. I want to cut all the structural parts for the base out of a single sheet of plywood, four feet wide and eight feet long, and one and a half inches thick. This will minimize the material cost and reduce the amount of labor, as we will have to put only one sheet onto the CNC bed.

I settle on an eighteen-inch overhang. In my mind, I’ve been visualizing all the parts required to make the base. I draw each of them, and then start dropping them onto a single sheet of plywood, arranging and rotating them so that they all fit. The final layout looks like this:

That’s it. I’m done. Andy will use my drawings to make another set of drawings, fleshing out my design ideas, formatted specifically for the client’s perusal. These are called “shop drawings,” or “shops.” If the client doesn’t like something that we build, and we haven’t shown or mentioned it in the shop drawings, then it’s our responsibility to fix it. If the point of contention was explained in the shops, and the client either missed it or didn’t understand what was shown, then they have to pay for any fixes. Theoretically, the Eurofurn guys should be able to look at the shop drawings and understand what the table will look like. But I decide to put together a quick 3-D model and use it to generate some renderings. Adding this type of image greatly reduces the chance of disagreement down the road. They show what most people care about—the look—in a way that’s easy to understand. Here’s one of the images that I’ll send:

As you can see, this is much easier to comprehend than my design drawings.

Andy completes the shop drawings and sends them on Friday. Nigel approves them by e-mail later that day.

By the end of the week, Germany is a memory. I’m back to doing paperwork, talking to clients, and worrying about sales, cash, and marketing. The week I was in Germany, we received only seven inquiries. That was the worst performance since I started keeping records in 2011. This week was higher than average: twenty calls and e-mails. The pattern since the beginning of April looks like this: 12 : 9 : 21 : 7 : 20. These are wilder swings than I have ever seen. What does it mean? Is our advertising working, or not?

Sales for the week have been weak, totaling just $30,779. They’re all Dan’s jobs. Each one is near the $10,000 mark. If not productive, he’s consistent: he’s sold fourteen jobs this year, totaling $146,130. That’s an average sale of $10,438. This is lower than Nick’s total, $397,495, and average, $17,282. I have sold $200,110 and averaged $12,506.

Neither Nick nor I sold anything this week. Even worse, my last sale of April, to the tool company, is canceled, via a very short e-mail with no explanation. Take $15,301 off my total, and the sales for April are now just $146,677. A cancellation is unusual. We never got a deposit and haven’t done any drawings, so it’s easy to strike this job and move on. But what happened? Since we’ve only dealt with the general contractor, I have no idea who made the decision and whether the job was canceled or went to someone else. I could e-mail the contractor and see if he has an explanation, but if he wanted to tell me why, then he would have. Another mystery to contemplate over the weekend.

—

I SET OUT on Saturday with a mission: to buy some cars. I’m assuming that this will be a horrible experience, but since I’m in sales myself, I’m interested to see how they deal with me. My dream vehicle is the newest version of the Prius, both for the mileage, to lower the cost of driving Henry around in circles, and for the room. Everyone in my family is six feet or taller. The Prius V is much larger than the standard version. I’ve already decided that it will be perfect for me.

My wife will use the second car. The Camry wagon she was driving had three rows of seats. When I told her that I wanted to get a Prius, she asked how well it would handle the five of us on long trips. I had no answer, never having been inside one, so we agreed to look for a used minivan.

I check prices for a new Prius V and a used Sienna. The Prius is going for list ($27,600) or more. I find a nice used Sienna at a local dealer—I’ll call it Urban Toyota—and head over to check it out. When I get there, I find that the office is being rebuilt and they’re doing business from construction trailers. I enter. The room is full of cheap desks and chairs, some occupied with salespeople and customers. There’s an office to my right where I can see a bunch of young guys, all dressed in suits and clip-on ties. I’m standing there, but nobody greets me. After a couple minutes, I stick my head in the office. “Are you the sales guys?” A man behind a desk confirms that this is the sales department. “Can I get some help?” Desk Guy points to a young man sitting on a stained sofa. He heaves himself to his feet and sticks out a hand. “I’m Chet. How can I help you?” I explain what I’m after—the Sienna—and that I am also in the market for a Prius V. I would like to test-drive them both. And if I like them, I’ll buy them, today, cash on the barrelhead.

Chet has other plans for me. “OK, here’s the first thing. We need to prep the Sienna for the test-drive. And I only have one Prius, and that’s going to need prep, too. Take a seat.” I sit and wait. And wait. And wait. Almost half an hour later, he comes back with the keys to the Sienna.

I take it for a spin—very nice, quiet, roomy, runs fine. This car has 63,000 miles on it, and they want $19,600. Pricey, for what it is. I tell Chet that I’d like to try the Prius and then we can talk. Back in the trailer, I start waiting. While I’m parked there, I can’t help overhearing a deal being closed to my left. A salesman is sitting with a family of six—husband, wife, and four small kids. The husband and wife are speaking to each other in Spanish.

Their salesman is busy with his computer. He’s a one-fingered, look-for-every-key typist, so it takes him a while to write up the deal. As he types, he explains what he’s doing, slowly and loudly. This deal is all about the monthly payment and the trade-in value. The couple is nervous. The salesman promises that “you can drive home in a Brand. New. RAV-4. Today.” He slides a pile of papers over, and the husband starts signing. The wife has a stricken look, but the husband and kids are very excited, and the salesman sports a broad grin. What am I seeing? Is this a good deal? A happy purchase, mutually beneficial to both parties? Or something more one-sided? That’s a whole lot of paperwork that the guy signed without reading any of it. Good luck, folks.

It’s been forty-five minutes. I’m just about to bail when Chet comes back in. “Here ya go,” he says as he hands me the key. “It’s out on the lot, I’ll follow you out.” The car is pulled up near the door. This is my first look at the Prius V. I get in and find, to my surprise, that there’s nothing on the dashboard: no dials, nothing analogue, no information at all. My old cars predated digital readouts. There doesn’t even seem to be an ignition switch. Chet climbs in. “Put your foot on the brake,” he commands, then he leans over and pushes a round button in the center of the dashboard. The display jumps to life, but there’s no engine noise. Is it running? “OK, this car is kinda weird. Watch how the shifter doohickey goes. Ya push it over into D, then just let her go, and she’ll spring back to where she was. Keep your foot on the brake. Same thing with reverse. OK, let’s get this over with.”

I gingerly press the accelerator and we move forward, gently, slowly, out to the street and through a five-mile test ride. When I accelerate, I can hear the engine spring to life, but there’s not much pickup. We return to the lot. I sit in the backseat—plenty of leg and headroom—and I can see from the digital readout that I was getting mileage in the high forties, just as I wanted. But in all my research, nobody mentioned that a Prius V can barely get out of its own way. I’m wondering whether I’ll learn to live with such an underpowered car. But I’m already sick of car shopping. I decide to proceed to a deal.

Back in the trailer, I tell Chet, “OK, I’d like to take both cars. You want nineteen thousand six for the Sienna and how much for the Prius?” Chet types a bit on his computer and looks back to me. “Twenty-eight seven fifty.” That is $1,150 over the sticker price on the car. I decide that he must just be playing to see if I’m stupid. “How about I give you forty-four five for both of them? I’ll write you a check right now.” He thinks about this for maybe a quarter of a second and then stands up. “Nah. I think we’re done here. Good luck with your search.” He heads back to the holding pen. I’m stunned. Did he really just walk away from someone who was ready to hand him money? Was my offer some kind of insult? I puzzle over the experience on my way home. Chet treated me like garbage, but why?

—

MONDAY, 8:58 A.M. I can see the crew gathered at the square table, ready for the meeting. There’s no chatter. They wait. For me.

What will I say? I normally do the numbers, then some commentary about how things are going. Our cash position is worrisome. We have $135,782 on hand, less than a month’s worth at our present spending rates. We don’t have much of a backlog. We are far, far behind my sales targets. It seems like things are slowing down, although I can’t put my finger on exactly why. I don’t want to confess that the situation is bad, that I don’t know what’s going on, and that layoffs will arrive next month. But that’s how I see it. Can I lie to them? Should I cancel the meeting? Or would they prefer a warning?

Before our last disaster, in the summer and fall of 2008, The Partner insisted that I not talk about our financial situation with the employees, that it was too much for them to handle, and that the good ones would jump ship and look for other jobs. Our partnership agreement said that we both had to agree on a course of action—each had veto power over the other. I still trusted The Partner’s judgment back then, so I followed his orders and kept quiet.

I never felt good about that policy. There were days when my longtime, trusted employees asked me directly whether the company was in trouble, and I had to keep mum. It was an enormous mistake. I found out later that all the workers knew it was very bad, and in the absence of any real information from their bosses, wild rumors were spreading. Morale was in the toilet. On the day that I laid off half the staff, I was surprised by how happy and relieved everyone was. Hearing the truth, even when it’s dreadful, is comforting. I promised the remaining employees that I would always tell them what was happening from then on.

Which brings me back to my Monday meeting. I drag myself out of my chair. Chin up. Shoulders back. Walk out there like a boss. Stand and deliver the truth. “Sales are not where I want them to be. Dan and Nick and I are doing everything we can to close some deals. Think back to 2009. Even in the worst year ever, we sold a million and a half. Something is going to come in soon. We have almost as much cash as we started the year with, which is not so bad. We need to finish the jobs we have on hand efficiently so that we can collect the money they owe us. Does anyone have any questions?” No. “OK, that’s the meeting.” They rise and return to their benches, machines, spray booth, desks, and broom.

—

TWO DAYS LATER, mid-morning. I’m working on a proposal when Bob Foote, my shipping manager, comes through the door. “Do you have a minute?” He has that look on his face that I recognize from years of interruptions. Something is wrong and I have to deal with it. He continues, “There’s a thing—Sean and I want to talk to you, if you have time. If it’s OK. If you’re not busy. I don’t know. Maybe after lunch.”

“What’s the issue?” I ask. He doesn’t respond. I lead him to my private office and shut the door. “OK, what’s up?”

He hesitates. “I don’t want to be a jerk, or anything.” Another pause. “Sean and I have been keeping track, and we think that Eduardo is cheating on his time sheets. He’s turning in hours when he’s not here.” Shit. I didn’t need this at all. I have things to do. But now I have to fire Eduardo.

Firing a worker is the most unpleasant thing I have to do as a boss. Fortunately, I haven’t had to do it often. The first time was shortly after I opened my doors. I (stupidly) hired a temporary worker even though I knew she was a junkie. She showed up and did some work. While my back was turned, she stole a check out of my checkbook, forged my signature, and then used it to buy cigarettes at the corner store. The grocer knew her well so he called me to make sure it was OK. Of course it wasn’t, so I told her not to come back. But the agony of that confrontation—I was twenty-four years old, had no idea what to say, and had no idea how she would react. Fortunately for me, she wasn’t surprised, she didn’t make a fuss, and she left. (What was she thinking, using the check on the same block she stole it? Junkie logic.)

It was eight years before I had to do it again, but the second time was even worse. This was a full-time employee, Nate Morgan, who had been with me for four years. His work wasn’t great and his attendance was spotty, but I liked him and kept finding excuses for his failures. Finally, he didn’t show up one day, even though I had emphasized that he was needed for a critical delivery. No phone call, no nothing. When he rolled in the following day, I was furious and told him it was over. He was astonished—apparently all the little talks I had given him about what was expected had made no impression. Or he thought that I would never go through with it. He begged me for another chance, tears rolling down his cheeks. But my other workers were sick of his failures and one guy told me that if I didn’t fire Nate, he would quit.

So I steeled myself and fired him. I knew that he would have a hard time getting another job, but I did it anyway. After he left, I broke down myself. Depriving someone of employment is no joke. But the mood of the other employees improved immediately. And that taught me a valuable lesson: bad employees make good employees feel bad. It makes them wonder why they should follow the rules. If the boss doesn’t care, why bother? My workers are craftsmen and have their own standards for behavior: show up, work hard, and try their best to make a good product. Seeing a coworker get away with sloppy work and laziness is a slap in the face. They hate it.

For all the bad advice that The Partner gave me, he was correct about firing people. Shortly after another termination, he told me, “It’s not your fault. They do it to themselves. When you need to fire someone, just do it.” This worker was ruining projects with errors and hiding the faulty work under his bench. Which might not have led to immediate termination, but he was also falsifying his time sheets. The problems didn’t come to our attention for a number of months, by which time we had written an employee manual, at The Partner’s insistence, that listed acts that would lead to instant termination. These included showing up under the influence of alcohol or drugs and falsifying time sheets. Every employee is given two copies: one they keep, another they sign to indicate that they have read and understood the provisions. My expectations are crystal clear.

Which brings me back to Eduardo. I know what I have to do. But it’s still an effort to switch gears, to go into Crusty Boss Mode, to become the guy who will pull the trigger.

Eduardo has worked for me for seven years. When we needed a floor sweeper to empty dust bags and keep the shop clean, The Partner asked the groundskeeper at his country club, an acquaintance, if he knew of anyone who was looking for work. What followed was surreal. The groundskeeper showed up on the following Monday with six guys, ranging in age from about twenty to forty or more. “Take your pick,” he said. The Partner turned to the youngest—Eduardo. “Do you speak English?” Eduardo said yes, although we would later learn he could barely speak the language at all. “This one,” said The Partner, and that was that. I felt bad for the others, but The Partner waxed philosophic. “They were all OK, or the groundskeeper wouldn’t have brought them. But the young one will be the cheapest.”

Eduardo was a good worker. Eventually we decided to see if he could do some woodworking. With training, he was OK at the simpler assembly tasks. He was reliable, worked hard, and followed directions.

Being an immigrant with brown skin caused him difficulties outside the shop. On January 21, Eduardo did not show up. As our company policy requires, he left a message saying that he was unexpectedly held up in New York and would be back in two days. When he came back, I asked him what had happened. He had been driving his cousin’s car, and for reasons he couldn’t or wouldn’t explain, had been pulled over by the police. They looked inside the car and saw a plastic toy pistol that one of the cousin’s kids had left on the backseat. Apparently this is a felony in New York. So Eduardo was arrested, released on bond the next day, and given a court date about a month from then. He showed me the court documents, which confirmed that the problem was the toy gun. I could picture what would happen next—defenseless Eduardo, who barely speaks English, becomes a pawn of the New York criminal industrial complex. I called a friend of mine, a criminal defense attorney in Brooklyn, and asked for help. When Eduardo showed up in court with competent counsel, all charges were dropped. It cost me a thousand dollars to set this up.

But now Eduardo has broken my rules, and in a way that I can’t ignore. I have to fire him. First, I call Bob and Sean into our small conference room. They’re nervous, as you might imagine. I open by telling them that I’m going to be firing Eduardo within the next hour and thank them for having the courage to come forward with this. That it is a testament to their value as employees and their faith in the company that they wouldn’t tolerate theft. That it is entirely proper to act in the interests of the company, as the company is the foundation of all our prosperity. And that the problem is not their doing, but Eduardo’s. And I ask them to repeat what Bob had told me earlier, with details.

Their story is detailed and believable. They show me their written notes and the discrepancies with the reported hours. I check my records, and they confirm the story. And then something curious comes out: it turns out that the week before, they took the problem to Steve Maturin, the shop manager, and showed him the same evidence. Steve Maturin heard them out—and then did nothing. Fantastic. Now I should fire Steve, too. Can I continue to employ someone who would ignore a case of theft from the company?

But I need to sort out Eduardo first. I write a description of the problem, a summary of the dates involved, and a quotation from the company handbook referring to the policy violation, and the consequence (immediate termination). The document concludes, “The undersigned, Eduardo Lopez, admits that these events occurred and understands the consequences of his actions,” with a signature line and a date. I have Emma review it and tell her that she will be sitting in on the firing as a witness. And it will be recorded on video. This helps me keep up my resolve and provides evidence in case Eduardo files for unemployment compensation. If he is fired for stealing, he is ineligible, but if it’s lack of work, or even incompetence, I have to pay fifty-two weeks of benefits. It’s also incentive for everyone to behave civilly.

I set up the camera and tell Emma to find Eduardo. When he comes in, he sees the chairs and the camera. He knows that this is trouble. I motion him to the chair across from me, and Emma sits down next to him. I begin. “Eduardo, I’d like to record this meeting. Do I have your permission?” He agrees, barely audible. “It has come to my attention that you have turned in time sheets for hours that you were not in the shop. This was witnessed on April seventeenth, April nineteenth, and April twenty-fourth, and reported to have happened on other occasions. This is a violation of company policy. Here is the handbook with your signature on the cover. You acknowledged that you read it and understand the policy. Here is the page with the causes for immediate termination. Look at number three: falsifying time sheets. Your employment here is now ended for violating this policy. I’m sorry, but you have to go now.” His face has turned bright red. He has tears in his eyes. “Eduardo, do you have anything to say?”

After a long pause, he asks me, “Can I pay you back? Can I pay a little every week? I will never do this again.” It’s tempting—my resolve weakened when I saw his tears. But then what? What about Bob and Sean? Will they think that stealing from the boss is acceptable, at least the first time you try it?

“I can’t have you here anymore, Eduardo. I can’t have the others see you working here after this. This is the choice you made. If you needed money, you could have asked me. I’ve helped you before. You made a different choice. You did this repeatedly. It’s not something I can tolerate. Now you have to go. Please sign this acknowledgment that you understand what happened. And if you file for unemployment I will contest it. But if you want to use me as a reference, I will never mention this. I will tell them that you are a good worker and that you left because of the long commute. I want you to have another chance, and I’ll help you with that. But you can’t work here anymore.”

Neither of us have any more to say. He signs the paper and walks out. I turn off the camera. Exhale. “Well, that sucked.” Emma looks a little upset but shrugs and says, “He had to go. You had to do it.”

Now I have to deal with Steve Maturin. This is a more complicated problem. Since he ignored theft, I should fire him. But he’s in charge of the shop, so removing him will cause a lot of disruption. I will also have lost a third of my production capacity—two out of six workers—in one day.

Steve Maturin is like a machine. He arrives exactly at five-thirty a.m. every morning and works steadily and efficiently all day. His completed projects are immaculate. He never wastes time with small talk. He won’t even speak unless spoken to. He eats lunch at his bench precisely at noon and leaves at exactly two-thirty p.m. During his nine hours, he will complete more work than anyone else in the shop. My records show that he has consistently been the fastest, highest-quality worker I have had. I’ve never hired a new person who didn’t tell me that Steve is the best cabinetmaker they have ever seen.

Steve has been around forever. I hired him in the fall of 1993 and made him the shop floor manager a few years later. At that time, I had three guys building furniture and I did everything else: sales, design, engineering, administration, finishing, delivery, and overseeing the shop floor. I needed to push some of that load onto someone else, so I put Steve in charge of the shop. I chose him because he was my best craftsman. Shouldn’t that person be in charge? After promoting him, I heard from the other workers that he was very fair, didn’t play political games, had no favorites. They accepted him as a leader.

Nineteen years later, he’s still building stuff and running the shop. He has performed this job even as we got much larger, moved twice, switched our products from furniture to conference tables, downsized after the recession, and rebuilt the business. He has never complained or asked for help, even during the worst crisis. His management responsibilities—reviewing drawings with Andy Stahl, assigning the jobs to different workers, monitoring work in progress—seem to get done in very little time.

We rarely speak. He seems to avoid interactions with me and I don’t stop by his bench unless I have something specific to tell him. When that happens, he’ll listen to whatever I say without comment and answer direct questions with as few words as possible. I would go so far as to say that Steve dislikes me, except I can’t think of a reason why he should. I’ve always gone out of my way to praise his work to the others, and he is the highest-paid guy in the shop. Over the years, I have seen him laugh and joke with some of the other guys. He’s never even cracked a smile with me. Frankly, his silence intimidates me. I know that I should have a better relationship with him, but I can’t figure out how to get past his defenses.

Aside from a frosty relationship with the boss, Steve has one other weakness: he is not innovative. I can’t rely on him to look at operations, identify possible improvements, and implement them. I don’t know whether he doesn’t care enough or isn’t capable of it. He doesn’t seem to spend any time making sure that the other workers do things the best way. I often see workers making choices on how to build a project that will get them into trouble, and I wonder why Steve doesn’t set them onto the right path. He clearly doesn’t like to interact with anyone beyond the bare minimum to divide the work up. So the shop is stuck. We don’t identify best practices, don’t make sure that everyone does things the same way. I’m too busy trying to deal with customers and administration to take over shop management myself. I’m mystified. Does he already have too much work to do? Does he have plans that he can’t implement for some reason? I have no idea.

I think that he’s unhappy that the shop has shifted from making a range of furniture items to just conference tables. I sympathize to a certain extent, but we can’t make any money doing this and that. It’s not efficient, in either marketing or production. If all my people were willing to work for ten dollars an hour, maybe we could survive. When everyone wants a high wage, and they all need to make mortgage and car payments, we have to face reality. Conference tables work as a business. Fine furniture does not. I’ve never heard him comment on whether he likes making conference tables but his demeanor speaks for itself. Always grim. The jokes and smiles have disappeared. He arrives, does his job, and then goes home.

The firing of Eduardo brings his failings into sharp focus, but I have to take some responsibility as well. I have done a very poor job of managing Steve. His resistance to any interaction with me has kept me away from him, but I have not put any effort into teaching him what I think a manager should do, nor made much comment on his style of running the shop. I have been lazy, or intimidated, or maybe overwhelmed by my other duties. And now I face the consequences.

First thing: I decide that this is not going to be Steve’s last day. But I still need to talk to him. I send Emma out to find him, and he arrives a few minutes later. He sits and looks at me, silent.

“I just fired Eduardo.” No reaction. “He was falsifying his time sheets.” Silence. “Apparently this was brought to your attention? And you did nothing?”

He shrugs and replies, “I was busy.” Pause. “Getting work done.”

Now I’m getting angry. “Do you realize that in any other company, you would be fired for this? You are in charge out there and you ignored an incident of theft? I should fire you right now.” I wait for a few seconds, but he just stares at me. Unbelievable, but, as usual, I fill in the silence.

“I’m not going to fire you today. I’d love to, but I have to take some responsibility for your weakness as a manager. I never told you what to do when something like this happens. I didn’t think I would need to tell you, but apparently I do, so it’s on me. So here’s what you do: you have a problem you don’t want to deal with, just bring it to me. It’s not so hard. I have to be the one to fire someone anyway. From now on, when you have an issue, I want to hear about it. You got that?”

His only reply: “Yes.” Then he sits like a stone.

“OK, we’re done here,” I tell him. He stands, turns, and heads back to his bench without a backward glance.

My thought as he walks away: Why didn’t I fire him? Why not do it and deal with the consequences? Do I need him that much? Maybe. Probably. I don’t actually know. What happens if he’s gone? How does that affect our deliveries? Who will replace him? Can I run the shop myself? Can one of the other guys step in? Or am I just being weak? Why do I always let this guy get away with disrespect? Why didn’t I give him a better speech? You did the right thing—don’t act out of anger. You’re a fool—taking the blame for his failures.

I’m furious with myself for losing control of the situation, for being such a coward, furious with Steve for his attitude, with Eduardo for being so stupid and causing all this mess. And it’s not even noon. For the rest of the day I can’t unsee the look on Eduardo’s face when he realized he’d been caught. What would I do if it were me? How would I explain it to my family? Would I even go home? I’ve never been fired. Could I wake up tomorrow and start looking for a job? Was I too harsh? What else could I do? My pity is accompanied by a less compassionate line of reasoning. Eduardo has done me a favor. He adjusted my workforce to fit a falling sales scenario. Our biweekly payroll will drop about fifteen hundred dollars, but over the course of the year it will yield about twenty-five thousand in savings.

The next morning, I steel myself and ask Steve who will be building bases. I don’t mention Eduardo. I just want to put yesterday’s mess behind me. Steve tells me that he’s going to have Will Krieger do it. That’s a good decision. Will is very fast, and his bench is right next to Eduardo’s, so he’ll be able to jump right into the work. Since I agree with the choice, I say nothing more. Steve has already turned back to the project he’s working on. It’s like nothing happened.

—

AT THE MEETING on Monday, I go over the numbers, then I pause. I need to say a few words about Eduardo. I’ve been dreading this moment all weekend. Here goes nothing: “Some of you may have noticed that Eduardo hasn’t been in for a few days, and you might have heard what happened. Eduardo was fired for falsifying his time sheets. Honestly, I didn’t expect this from him. I don’t know why he did it. I don’t care why he did it. When I find out that someone is stealing from me, I will fire that person on the spot.” I look at everyone—everyone’s paying attention, even Steve. “Falsifying your time sheet is stealing from me, and stealing from all of us. If we’re spending money on payroll and not getting work done in return, it weakens the company. It makes it harder for me to pay the rest of you, and to pay my bills. Not a good thing. I’d like to thank the guys who brought this to my attention. You did the right thing. I want this company to provide for all of us, and to do that, we can’t have thieves here.” I pause, trying to figure out how to wrap this up. “I don’t think, with this crew of guys, that we will have this problem again. I hope not. If we do, I’ll fire that person, too.” Speaking off the cuff is not going well. I’m not finding a way to turn this into an inspirational address. “Anyway, we all have work to do. That’s the meeting.” It’s the worst pep talk I’ve ever given. I turn and walk away. One of my special powers as boss: when I stop talking and leave, the meeting is always over. And the flip side is that when I go, I can’t see what I’m walking away from. I’ll never know what my people really think about Eduardo. I hope that I did the right thing.

—

AFTER LUNCH I take a break from spreadsheets and e-mails and go out to the shop. Ron Dedrick has started building the Eurofurn prototype table. All the parts have been cut on our CNC, and he is gluing a strip of solid walnut to one of the top pieces. As I anticipated, this is a very complicated clamp setup. Ron sets each clamp in position, then tightens the screw handle to just the perfect amount of pressure. When he’s done, I ask him how long it took. “With prep for clamping? That took a good hour. Milling walnut took about half an hour. This is the second top blank, and it went better than the first. The edge on the first cracked and I had to rip it off and start over. All morning, and I just have two done.” I take a good look at the first top piece, which is still in clamps. It’s going to take him much of the day to do this operation. I saw a machine at Eurofurn do a similar operation in a couple of minutes. I should qualify that statement. A machine that Jens told me cost $740,000 did it in a couple of minutes. And if I borrowed the money to buy that machine and paid it back over time? Ron is still cheaper, per hour. For that much money, I can employ Ron for more than fifteen years. And he can switch from one type of product to another very easily, and make sure that the wood on every one is beautifully arranged. What he can’t do is turn out hundreds of tops a day. If we need to build tops that fast, I’ll have to find a better method than the one he’s using right now.

Over the next couple of days, Ron completes the prototype. The removable panel in the base is very tricky. It needs to fit precisely into the opening in the base. Even a tiny fraction of an inch too wide, the latches won’t work. Ron completes it in two days after the top is finished.

My shop drawings show a hole in this panel that can be used to get a grip on it. Without the hole, there’s no indication that the panel comes off, and no place to grip and pull it. Ron has cut the panel to exactly the right size. He has mounted the hardware and pressed the panel in place. Then he comes to get me. All three panels—two permanently glued, one removable—present a smooth, unbroken surface. No gaps anywhere between the panels and the solid pieces that make up the sharper corners of the base. A triumph of craftsmanship. But I can’t tell which panel will open. The hole at the top of the removable panel is invisible unless I get down on my knees to look for it. Hmmm. Nobody is going to do that. You should be able to look at this base from a standing position and, at a glance, know what to do and how to do it. I ask Ron how well the latches work. He smirks. “Try it.” I have to put a lot of oomph in exactly the right place to pop the panel off. And when it finally releases, I have been pulling so hard that I nearly fall over backward. Ron’s smiling with his special “this is a stupid design, even though I built it perfectly” face.

“OK, we need to make this easier to operate. I’ll get Andy to find different hardware. I want enough of a gap to show that the panel is removable. And we can add a notch to the base behind the panel so that we can get fingers behind it to pull. That should do it.” These modifications make it much easier to remove the panel. It would work even better with another hole or a knob at the bottom of the panel, but that will clutter up the clean surfaces that Eurofurn loves.

The hatches that cover the power/data ports on the tabletop are also problematic. In Germany, they use a small, sleek, precise hinge and have custom machines to cut the special holes required. Those hinge cutters cost fifteen hundred dollars each, and you need two of them to cut left and right holes. The hinges we’ve chosen don’t require special equipment and they are invisible when the hatch is closed, giving us that very clean, very sleek Eurofurn look. But when opened, the hinges are quite prominent. Our solution isn’t as elegant as the German hinges, but we’ve shown what we intend to do in our shop drawings. And they approved the design. Ron builds these hatches exactly as shown in the drawings. They work fine.

I’m tired of paying good money to rent a PT Cruiser, so on Thursday I head to a local Toyota dealer—I’ll call them Automall Toyota. I got an online quote for a Prius at five hundred dollars under list price, but the dealer that sent me that quote is a hundred miles away. I thought that I’d stop by Automall and see whether they would match it. My experience is a stark contrast to Urban Toyota. A receptionist greets me immediately and a salesman is at my side within a minute. He’s about my age, about my height, slim and professional looking. His name is Steve. I tell him that I want to see the big Prius. He returns with keys within three minutes. Once we are in the car, he insists on going over the controls and draws my attention to three buttons between the two front seats that change the driving mode. Driving mode? Yes, this car can transform instantly from an eco-friendly fuel sipper to a howling rocket sled, with an intermediate step in between. We head off in the eco mode, and I recognize the sluggish golf cart that I drove the week before. Steve leans over and punches the power-mode button, and suddenly it’s an entirely different car. It handles a steep highway on-ramp without difficulty. We take it out onto the local expressway and it drives very well.

Back in the showroom, I pull out my price quote. “Here’s an offer from WayFarAway Toyota, for the car at $27,100. I’d rather not drive a hundred miles, so if you can match this, I’ll write you a check right now.” Steve checks with the manager, and a couple of minutes later, he’s back with the paperwork. Deal.

Automall Toyota seemed to know exactly how I wanted to shop: they clearly explained the product, showed some flexibility on the price, didn’t waste my time, and got my money. I picked up my new car the next day. Could I have gotten an even better price? Maybe. But I like to buy things, enjoy them, and not look back. I’m still wondering why Urban Toyota didn’t seem interested in my business. Oh well, their loss.

My sister solves the minivan problem. She’s selling her 2009 Sienna. My nephew is just starting college, and she can’t handle tuition bills and a car payment at the same time. She wants $14,000. Done. Solving my car problem cost me $44,000. I still have $34,000 to live on for the rest of the year. As long as Peter doesn’t start college in the fall, I’ll be OK.

—

MY MONTHLY VISTAGE meeting falls on Tuesday, May 15. We all start the session at a whiteboard, giving scores for both our personal life and business prospects. We’re using a scale from 1 (suicidal) to 10 (euphoric). I can give myself a reasonable personal score, but how should I rate my business?

It’s a tough question. I’m trying to organize an unruly set of facts into a coherent story. This narrative needs to be both an assessment and a prediction, combining recent events with what I think will come next. I have all kinds of material to work with, but my mind returns consistently to a number of distressing trends. Inquiries seem to be drying up. Halfway through May, and we have booked just $71,321 in new orders. We stand at $787,550 for the year, far behind my target of $900,000 for this date. The Germans think I’m special, but they also told me that Europe is suffering from a dismal economy. And the newspapers tell me that the United States might be headed for another recession. We sell to a very wide range of customers, and every day Google tells me that thousands of people search for our product. Where are they? Who are the people who might have clicked, might have called, might have bought, but didn’t? What changed their minds? Am I about to become victim to another crash? As in 2008, I don’t have a lot of money on hand, and can’t expect much more in the near future. I don’t have a pipeline full of orders. I survived the last crash by laying off workers and cutting everyone else’s pay. I’m not sure that I have the stomach to go through it again, and I’m not sure that we’ll survive another down cycle. I rate my business prospects: three out of ten. My score is by far the lowest one on the board.

We’re all sitting around one large table. Ed Curry asks each person to give a brief statement about the score they have given themselves, adding whatever detail they wish. As it happens, I’m one of the last to speak. Business scores for everyone else range from seven to nine. Orders are coming in. Nobody else is crying doom or seeing sales slowing down. When it’s my turn, I give a recap of my situation and explain my theory that, as a broad indicator of business confidence and activity, my business is the canary in a coal mine. Inquiries are falling because fewer people are shopping. Sales are falling because those who do shop are choosing cheaper options. Everyone’s pulling back on spending. Get ready! Rough water ahead!

No heads are nodding in agreement. Keith DiMarino, who owns a company that stores and shreds documents, raises his hand. Over the months, his advice has been blunt but intelligent and on point. “Let’s start with one thing,” he says. “Whatever is going on here is your fault. You did something. I don’t want to hear any more whining about the big world collapsing and poor me being a victim. I don’t see it. Nobody else sees it. You have done something to make things slow down. Even if your story is true, and we’re all doomed, it doesn’t matter. You have to fix it. It’s your problem. You. Stop complaining and get started.” This is not what I want to hear, but nobody else has different advice. Further discussion focuses on what I might have done to mess up my marketing. I don’t know what to tell them. I haven’t made any changes since early March. Our Web marketing is working fine—page views are steady, within the same range that they have been for the last year. But incoming calls and sales are collapsing.

As I leave, Sam Saxton pulls me aside. “You have to call my sales guy. He’ll help you. Just call him, have a meeting, see what you think.” I remember that Sam had urged me at the last meeting to call the consultant, but somehow, between Germany and everything else, I haven’t done it. I’ve never hired a consultant before. But Keith told me to start fixing things. The next morning, I call Bob Waks. We arrange for him to come out to the shop on the twenty-third.

I don’t find time to look at my marketing until Saturday. On the weekends, the shop and office are quiet. I want to think everything through, and this requires focus.

—

OUR MARKETING EFFORT, in its entirety, consists of four interacting efforts. First is product development, the group of things that we offer for sale. Second: the Web site, which presents our offerings to the world. Third: Google, both free search results and AdWords, which directs people to our Web site. Fourth: the sales department, which responds to each inquiry with a proposal. I’ve made no changes to this overall structure since 2009, when I launched a new Web site. So if I did something to degrade our marketing, it must have been on a smaller scale. So which effort is the most variable? Where should I start looking?

The problem is that I’ve tinkered with all of them for years. I constantly develop new table designs, photograph them, and put them up on the Web. Google makes note of these changes in some mysterious way and then shows our site in a better or worse position. We have settled on a basic game plan to respond to incoming calls, but Nick, Dan, and I each have different design ideas, writing skills, and graphic sensibilities. I don’t always have time to review what they send out. And nobody looks over my shoulder. Any one of us could be losing sales without knowing why.

I decide to start with Google. I have access to enormous amounts of data, in both AdWords, which looks at my paid search results, and in Google Analytics, which looks at all aspects of site performance. I log in and start looking through both sites. They are bewildering. Google’s interface allows me to examine every possible aspect of my campaigns in multiple ways. There are statistics, graphs, change records, hundreds of links to rearrange the view this way and that, pop-up screens with more information, little warnings and suggestions, modeling tools to game alternate scenarios, et cetera, et cetera. If there’s a malfunction hiding in all that, it’s not obvious where and what it might be.

AdWords serves my ads each day, at a wide range of costs for each click, until my daily budget—$450—runs out. It’s not clear exactly what time that will happen, as the cost of each click is dependent on a bunch of variables. Google shows my ads about sixty-five hundred times a day, and from that we are getting about a hundred clicks. Only a couple of the clickers contact us—our average for the past two weeks has been two calls a day. A year ago, the same inputs were producing 3.2 calls a day, and our sales were much better. Nothing I can see tells me what’s different this time.

I have fifty-eight ad groups, each serving a different ad tailored to a set of similar keywords, 403 in all. Each of these ad groups behaves differently. Some get a lot of traffic, but a very low percentage of viewers click my ad. Some are the opposite. I can’t tell which ad groups prompt the most calls, e-mails, and sales. When I’ve asked people which ad they saw initially, nobody seems to remember. And since we don’t sell directly from the Web site, the answer to this question isn’t in any of this data. I can see that I’m spending a lot of money on clicks and that this seems to be producing the same number of views and clicks as it did a year ago. And yet our calls and sales are dropping. Why?

I spend a couple of hours clicking this way and that, getting more and more frustrated. There is only one consistent message from Google, delivered in a variety of ways: I should be spending more money. I am missing clicks that are available with a larger daily budget.

What to do? If I make a bunch of changes at once, I won’t be able to tell which ones worked. And I could make things worse. I don’t put much stock in the messages recommending an increased spend. Of course Google would say that. It’s their business. If they were really trying to help me, the interface would be more user-friendly. They seem to be drowning me in facts without providing any way to make sense of it all. I head back home, still worrying.

—

MONDAY ARRIVES AND I give another honest/discouraging speech. It’s a repeat of the past two weeks: sales slow, cash disappearing, but we aren’t out of work yet, so keep going as fast as you can. After lunch, I receive a curious phone call from an office furniture dealer in California named Jim. “I’ve got your proposal for Cali Heavy Industries here,” he says. This is Dan’s job, the one his contact at Cali Heavy told him we were getting. Jim tells me, “I really like what you guys have done in this proposal and I want to find out more about your company.” I tell Jim our story, and he says, “I love this. We could use somebody like you. The big manufacturers can’t handle really large custom tables. I get stuff like that all the time, and I have to pass on it.” He promises to be back in touch if any of his projects include custom work. This could be another outlet for us, like Eurofurn, but we wouldn’t have to copy another company’s style. We could do our own work, our own way, and just sell more of it. The dealer would get a healthy cut, but if they were selling a huge amount of other furniture at their normal prices, they might accept a smaller markup on the custom jobs, so that they can offer a spectacular table as an extra incentive to their customers. This could work out well. Between Eurofurn and dealers, I could decrease my reliance on Google.

Dan’s happy, too. “I’ve done a ton of work for Cali Heavy. I just sent them complete plans of our table. My guy says the purchase order is coming any day now.” He’s been saying that for more than a month, but sometimes it takes these big companies a while to do the paperwork.

—

AFTER EVERYONE HAS LEFT on Monday, I log in to AdWords again. Inquiries have slowed to a trickle: twelve last week, eight the week before. Then I take another look at my Google budget, the maximum amount of money that they can take from me each day. I determine this amount, along with the ad schedule. I run my ads from eight a.m. to ten p.m. Eastern time, so that they are showing on the West Coast after the end of their business day. Google shows the ad when it receives a search string that it thinks is a good match for one of the keywords I have chosen, and charges me if somebody clicks on the ad. The cost for each click varies, depending on how much I offer to pay for it, how much other advertisers want to pay Google to show their ads, and whether Google thinks my content is a good match for the original query. When the summed cost of all the clicks I receive each day exceeds my budget amount, Google stops showing my ads.

Like Saturday, Google is telling me that my budget is too low. They promise that spending more money brings in more clicks. They have a helpful tool where I can punch in different daily budgets and see how many clicks they think I will get. For instance, it might cost me five hundred dollars to get a thousand clicks, a thousand dollars to get fifteen hundred clicks, and two thousand dollars to reach 1,750 clicks.

Google tells me that I could be getting hundreds more clicks per day if I bump my daily budget up to seven hundred dollars. But the additional clicks may not be of sufficient quality to result in additional sales. AdWords doesn’t promise that they will come at the end of the day from some previously untapped group of eager table purchasers on the West Coast, just that I will get more of them throughout the day. So who are the extra clickers? I presume they come because Google shows my ads to more people, even when the search strings aren’t such a good match for my keyword. Some number of viewers will click on anything, often by accident. That doesn’t mean that they have any interest in buying a big conference table. Google’s definition of a success is a click. They have no way of knowing if I make a sale from that click or not. Because I’ve always had concerns about whether more spending will actually get me more income, I’ve set my daily budgets at numbers that I feel I can afford, which is about 30 percent less than Google’s maximum recommended amount. That worked fine for years. But now, maybe, it doesn’t. So I decide to roll the dice and do what Google has been nagging me to do. I increase my daily spend from $450 to $650. That should get me 90 percent or more of the available clicks each day.

—

THE NEXT MORNING Nick has bad news. The Air Force job in Virginia has gone to another company. Forty thousand dollars that we had been counting on. I sympathize: “Those assholes,” and ask the obvious question: “What happened?” He tells me that he has had a bad feeling ever since he went on the site visit.

“It was a big meeting, with a bunch of companies. They showed a slide show of what they wanted—it was the proposal I sent them with our name removed. I thought it was a lock for us. After the meeting, I went to introduce myself to the officer who presented. He was standing out in the hall, talking to a guy from another company. They were laughing and joking, and they kept going on and on, so eventually I left.”

“You drove twelve hours to the meeting and back and you didn’t even talk to them?”

“I’ve been e-mailing them proposals for months. They know who I am.”

“You should have talked to them so they would put a face on all those e-mails.”

“Yeah, I probably should have. I thought we had this one for sure, though. They kept telling me how awesome the designs were and thanking me for doing all that work.”

“Give them a call, see what happened.”

Later Nick tells me that he’d heard back from the guy: our price was too high. On the Air Force contracting Web site, I see that the job went to the outfit whose salesman had been joking with the officer. The winning price was three hundred below our bid. We’d sent pricing along with our proposals, and the officer probably showed it to the company they really wanted to work with. We’ve been played.

The next day we ship the three Eurofurn orders that we received in early March. We haven’t received any new requests for quotes since I came back, so we only have to finish and deliver the prototype table. I presume that their sales are slow, just like ours. Or maybe they are waiting to see the prototype before committing to more orders.

At three-thirty, I have my appointment with Bob Waks, the sales consultant. He has a couple of inches on me, and I’m 6-foot-1. Blue blazer, golf shirt, tan slacks, tasseled loafers. Leather briefcase. Silver hair, neatly trimmed. Firm handshake. Laser-beam eye contact. “We finally meet! Sam has told me so much about you.” I take him out to the shop floor for a tour. Bob shows polite interest and then asks to see the sales office. He meets Dan, Nick, and Emma, and I show him a couple of proposals. Again, a polite but muted response. I’m expecting him to be amazed by our software models; I’m a little insulted by his lack of enthusiasm. We retire to my private office for further conversation.

“Why am I here?” is his first question. I describe our situation: falling inquiries, falling sales. I don’t know why the inquiries are drying up. I’m not sure what’s happening with sales. I’ve been through dry patches before, and they always corrected themselves eventually, but I’m afraid that this is going to be an especially rough ride. I’m almost out of work, and I can see that my cash will dry up soon as well. I tell him that Sam Saxton thinks he can help me. I hope that Sam’s right.

“I’m not sure that I can,” is his surprising response. “I’m a little worried about you. Whether we are a good fit together. Guys like you can be good to work with, or very, very bad. You are a classic boss, Paul. You make quick decisions, and that’s good. I don’t have to fight my way through layers of an organization to get to the decision maker. If Paul Downs says it’s a go, it’s a go. The problem is when I tell you something you don’t like. You might agree or you might fight me. If you fight me, we’re wasting each other’s time. I don’t need the hassle. I have lots of customers. And I can see that Downs is a smart guy, you can think on your feet, and you can talk your way into anything.” Yup, that’s me. “But you aren’t going to like what I’m going to show you about how your sales ‘organization’ isn’t working. Your first instinct will be to figure out how I’m wrong about you. Then you’ll start fighting me. Pushing back. Telling me how I’ve got it wrong.”

I think about this for a second. It’s true that I make quick decisions and that I’m used to having my own way. And that I can debate with the best of them. All my employees know this and never argue with me about anything. If I feel like it, I explain my decisions. If I don’t, I don’t. I’m not used to any push-back. Sometimes I wish I did get a fight from my workers. I know that they are smart people. They must have some good ideas. I must be wrong fairly often, or my business would make more money. But they don’t challenge me. Am I that intimidating? Possibly. I think that this is why I was interested in joining Vistage—to get someone to criticize me when I needed it. And this is why I called Bob. I want someone to take a hard look at how we sell.

At the same time, I’m not so sure that Bob Waks is the right guy. He is the classic salesman—tall, groomed, confident, articulate, and he gives off a sales-y vibe. Ice to Eskimos. Anything goes to close a deal. There’s nothing to dislike about him—he seems like a very friendly, smart guy—but he’s 100 percent sales. And this rubs me the wrong way a little bit. I’m used to selling a thing, and I close the deal by making the thing so good that it speaks for itself. No fancy double-talk required. We are craftsmen, and we fade into the background as soon as the job is completed.

I have to put my prejudice aside. I have Sam Saxton’s testimony that Bob is effective, and his numbers back that up. I want my sales problem fixed. I don’t know whether Bob is the solution, but I have to try something. So I reply, “It’s true that I make quick decisions. It’s true that I push back when I’m challenged. So what? That’s who I am. I’m also good at change. And so are my people. We don’t get hung up on yesterday, because yesterday usually sucked. I’m willing to take criticism. And I believe Sam when he says that you are good. So let’s presume that I’ll be good to work with and that you will help. What’s the next step? What do you actually do? When can we start? And how much will it cost?”

Bob tells me that he’s going to need a couple of days to put together a recommendation and a contract, but he’d like to set up the meeting to review them now. Am I available next week? I’m going to be in the Middle East the following week, but we set a date for Thursday, the thirty-first. I think I’ve been maneuvered into doing something, and I don’t like that. On the other hand, I’m heading in the direction that I wanted to go. I have nothing to complain about, other than a vague sense that I haven’t been in control.

On Monday, after another dismal set of numbers, I tell the crew that I’m doing everything that I can think of to turn things around. I tell them about increasing the AdWords budget and the consultant. After the meeting, I ask Dan and Nick whether any of their clients are likely to place orders this week. They don’t know, but promise to reach out to the most likely prospects. They are busy with outbound e-mails all morning.

Discouraging replies start arriving after lunch. The worst is from Cali Heavy Industries. Dan thought that it was a lock. Now Dan’s contact writes, “We have chosen another vendor to move forward with this project. Thanks for your hard work and good luck in the future.” I call Jim, the dealer. He’s “in a meeting.” Send him an e-mail. No response. That’s a thirty-five-thousand-dollar job, gone. Add that to the forty thousand in Air Force work, and we could have been in much better shape for May.

Thursday is the last day of May. First thing in the morning, I go over to Bob Waks’s office. His coy protest that he might not be able to help has been replaced with a multi-level plan of attack. First, evaluations. The fact that I have been making sales for twenty-six years notwithstanding, I will need to take a series of tests to see whether I am psychologically suited for the job. Dan and Nick will take the same one. It’s called DiSC Profile and is commonly used in business. I’ve never heard of it. I will also take another set of tests to evaluate our company sales practices and culture and my own performance as sales manager. Sales manager? Is that what I do? I never thought of my job that way. Bob will also come out to our office to observe us at work, so that he can better understand how we approach our job.

After the evaluations, training. Dan, Nick, and I will take a ten-week course on the basics of the Sandler method of selling. I haven’t heard of this either. I didn’t realize that selling comes in different systems, but it makes perfect sense. Every company makes sales and wants to make more. And some people are bound to develop a theory of how it should be done.

During the training, and continuing on for the next twelve months, we will also receive two monthly counseling sessions with Bob himself. These sessions will allow us to discuss the ongoing development of our skills and to get help with challenges that come up.

It takes about an hour for Bob to go through this. In the end, I have one more question: how much? For the whole package, $37,000. Holy smokes. On the other hand, I could continue doing what I’m doing, even though it isn’t working well. Sam saw his sales rise by 40 percent in the first year after the training, and he attributed all that to Bob’s work. If my sales rise 40 percent, I will have an additional $800,000 coming in the door. Spending $37,000 for that result is a bargain. I have to pay Bob $8,000 right away and the rest in monthly payments of $2,416.

The eight grand is 8 percent of my working capital. The payments don’t seem that bad. I ask Bob if I can put it on a credit card, and he says yes. That will help—I can give him the deposit, wait thirty days before I have to pony up cash, and retain the option of rolling the card balance if I’m still short on funds. I can’t do that for very long, but it will give me some time to see whether the program is working.

I asked Bob whether he would be willing to include Emma for the same price. She’s smart, and I want her to keep our clients’ point of view in mind. Nick, Dan, and I have a lot to win or lose, and that might cloud our perception of what we are being taught. Also, if the rest of us go through the program, she would be the only person in the sales office who hasn’t learned the new methods and the new lingo. I don’t want to have to explain it all to her while we are learning it ourselves.

Bob agrees and I sign the contract. I decide that I’m going to approach it with an open mind and do my best to learn something. After lunch, I give Dan and Nick an overview of the training and the cost. They look very worried. “This worked great for Sam Saxton,” I say, “and I’m sure it’s going to work for us. Look, I just bet thirty-seven thousand dollars that we can be better at selling than we are now. Sam’s sales jumped forty percent. If we sell forty percent more than last year . . .” I take them through the calculations I’ve performed to convince myself that this is a good idea. I need them to buy into the program or it will be an expensive waste of everybody’s time.

At the end of the day I take stock of the month. As usual, there’s no clear message to be assembled from the jumble of data and events. Things that seemed important at the beginning of May have faded in my rearview mirror and been replaced by fresh concerns.

The numbers for the month are mostly bad. Total sales: $114,042. We shipped the Company S job back to them on the first, and they paid me what they owed in the middle of the month. Inquiries for the past four weeks have been consistently terrible: eleven per week. Increasing my AdWords budget has bought us more clicks, but so far they haven’t translated into more calls. It’s also been another month of low build totals: $137,086 moved from the shop floor into the finishing room. If that’s all we have to ship next month, we’re in trouble. Surprisingly, our cash position did not deteriorate. I started the month with $105,203 on hand, took in $182,594, and spent $175,113. That means an increase of $7,481. Stopping my own pay made a difference. I will end the month with $112,684 on hand. At our current rate of spending, that’s enough to operate the shop for fifteen working days.