JUNE

DATE: FRIDAY, JUNE 1, 2012

BANK BALANCE: $107,096.18

CASH RELATIVE TO START OF YEAR (“NET CASH”): -$30,058.14

NEW-CONTRACT VALUE, YEAR-TO-DATE: $803,722

I come in early on Friday. There’s an e-mail from Bob Waks with a link to the personality test and sales self-assessment. He says these will provide an objective measure of how I am performing. He ends with a warning: answer the questions honestly, or you are wasting your time and money. OK, I think, an unbiased evaluation would be useful. My visits with Sam Saxton and my strolls through the Eurofurn factory have been eye-openers. I’d like to know how my sales efforts measure up. I’ve never taken a personality test before. The questions don’t quite make sense. I come to the conclusion that there are no right or wrong answers, just choices. It’s liberating. I rip through the questions and press Send. Now for the sales self-assessment.

There are two sections: one about selling, and another about being a sales manager. The first questions aren’t hard:

Do you know how to generate leads?

Yeah. Pay and pray. I give Google a ton of cash for the top AdWords spots and hope they show my organic results in a good position as well. And it’s been working great, at least until recently.

Do you know how many potential jobs are in the pipeline?

I’m keeping a tally of the leads that come in, and about half of them get proposals.

After a few more process-oriented questions, they take a different tack:

Do you want to succeed?

Of course. I’m sick of failure. Who doesn’t want to succeed?

Have you written down a list of your goals?

No, why would I? I just want to sell more; do I need other goals? I have a million e-mails to do every day; I don’t have time to write anything down.

Do you control your own emotions and behavior?

Absolutely. At least in front of my employees. And my wife and kids. Keep it all inside, locked down tight. I have to be strong.

How do you make major purchases yourself?

I do some research, make my choice, and slap my money down on the counter. Is there a better way to shop?

What is your definition of “a lot” of money? A hundred? A thousand? More?

I’m spending eight grand every day, selling tables that can cost fifty thousand dollars. A hundred dollars is a rounding error. It’s what the scrap in one trashcan costs me. A thousand dollars? Not much. A hundred thousand is a good pile of cheddar. A million dollars is a lot of money.

Do you have a system for selling?

Yup. Write a great proposal. Put a bunch of them out there, and some will come back.

Do you track your selling activity every day?

Nope. I’m sitting in a small office with Nick and Dan, so I know what’s going on.

When do you send a proposal?

As soon as I can! I want to put my info into my client’s hands before my competitors can even raise their pencils. The buyers always say how impressed they are by our speed. I’m sure we’ll score highly on this question—we can hardly do any better.

Do you know whether the person you are dealing with is a decision maker?

Sometimes, when they tell me. And I can always tell when it’s a boss on the other end of the line. But the others? We’ll give anyone a proposal, so that they can pass it up their chain of command.

Are you sympathetic toward your clients?

Sure, they’re nice people, mostly, and they want us to help them. Sometimes they get to be irritating—Eurofurn—but that’s just the way it is.

Do you want your clients’ approval?

Who doesn’t? Having them disapprove is hardly the path to success.

Are you willing to accept their excuses for delaying a decision or ending the project?

Sure. What else can I do?

Do you try to get them to make a decision?

Not really. Our proposals speak for themselves. If they appreciate good work, they’ll realize that we’re the guys to go with.

What do you tell yourself when a sale is lost? Do you blame external factors or accept responsibility?

Well, the economy has been pretty bad the past few years, and it looks like it might be getting worse again. And our product is good, our prices are fair. We’re doing the best we can. We’re not the cheapest guys around, and so we can’t be a good fit for everyone. Sometimes it’s just not meant to be. Everything I’m doing has worked for years; we’re just going through a bad patch right now.

Do you hold regular sales meetings?

Like, sit-down-with-an-agenda-and-watch-the-boss-bloviate meetings? Why bother? We’re all in the same room. It’s like a continuous meeting already.

Do you provide coaching and feedback for your salespeople after every proposal?

I should definitely do that. I told the guys to cc me on every proposal they send, and they’ve been pretty good about it. I don’t always have time to look through them, though.

Are you a good listener?

Of course I am. I have a unique ability: I can listen to a person talking to me and type an e-mail at the same time. It’s the only way I can get work done when my workers keep interrupting me. And I’m considerate. If they start to tell me something, and I’m still thinking about something else, I’ll very nicely ask them to start over.

Do you constantly look for new salespeople?

You mean someone who understands how to make our product, and knows our software, and can zip through a couple proposals a day? They aren’t out there. It was enough trouble to get Nick and Dan up to speed. I don’t have time to start that process over.

Do you use reasonable hiring criteria when choosing salespeople?

I think so. Nick was the only guy working for me who could talk on the phone, so he was the obvious choice. Dan had dealt with clients in his previous job, maybe not selling, but at least he had spoken to them. And he showed up at the right time.

Do you need approval from your salespeople?

Like letting them veto decisions I make about the company? Or are you asking whether I feel good when they respect me? I’m not sure what this means. But I don’t think those guys see the big picture, and I don’t have time to explain everything to them before I make my mind up. So no, I guess not.

Do you accept mediocrity from your salespeople?

Look, sales is chancy. Success and failure come in clumps. I don’t know why those guys can’t make a sale every day; it’s probably the same reason I can’t make a sale every day, not that I actually know why that is. I don’t like picking up the slack when they don’t sell, but that’s what the boss has to do sometimes. And what am I going to do anyway, fire one of those guys?

Have you ever fired a salesperson for poor performance?

I’ve only had two salespeople. I’m not sure that Dan has what it takes, but firing him would be pretty harsh.

Why not?

This question isn’t on the test, but the other questions lead me directly to it. Dan is lagging way behind Nick in sales. He hasn’t even passed the two hundred thousand mark, and we’re almost halfway through the year. I was hoping for at least eight hundred thousand from him by December, but it looks like I’m not going to get it.

I submit the results. Dan and Nick have just rolled in. I don’t feel like discussing the test with them—the line of questioning has been disturbing, to say the least. I e-mail them the link to their own assessments, asking them to complete them as soon as possible. As for my own test, I wonder how I’ll score. It’s strange to answer a bunch of questions about how I do my job and whether I’m heading in the right direction. I’m not used to being challenged in this way.

—

SATURDAY EVENING I FLY to Dubai, which is the last thing I want to be doing, not least because the trip will cost more than four thousand dollars. I arrive on Sunday afternoon. I have three meetings on Monday in Dubai. In the evening, I fly to Kuwait City, where I have four meetings on Tuesday and one on Wednesday morning. After lunch, I’ll fly back to Dubai to catch an early-evening flight home.

That’s a lot of meetings, especially considering that I’m not sure whom I’ll be meeting or whether the PowerPoint I have prepared will be impressive. I hope that my client list will be enough to show that we’re legitimate.

I’m also painfully aware of my company’s limitations. We’re not large, we’re not profitable, and the business seems to be collapsing. How can I be confident that I’ll survive long enough for this effort to pay off? How do I walk up to strangers, shake hands, and make a convincing promise of a prosperous and profitable future? I have no choice. I’ll put my problems at the back of my mind. I’ll just do it.

The next morning, I meet Bahar O’Brien. She’s my Commerce Department contact in Dubai and she’ll be accompanying me all day. She’s cordial but reserved. Just her tone of voice is enough to put me in my place: today’s American businessman, come to Dubai in search of riches. And, she seems to imply, not a particularly impressive specimen. Now I’m wondering about my suit—a summer-weight wool affair, in an attractive sand color, perfect for the Middle East. Or so the salesman had assured me back in Philadelphia.

Our first meeting is at the Al Reyami Group, a local conglomerate that does a little bit of everything, including design and construction. When we arrive, our contact doesn’t remember making the appointment, but he tells us he has twenty minutes. I pull out my laptop and start the show. The first slides show the table we made for the World Bank, an enormous oval forty feet long and twenty-four feet wide. One picture shows the finance ministers of the G20 countries sitting around it. Instant credibility. Our contact leans back in his chair with a smile. “I think we have something for you. I need to check with my boss. Give me a minute.” He’s back in five and takes us to see the head of the design department. I run through the slides again, and he calls one of their project managers. Twenty minutes later, we meet him and two designers. He tells me that they are renovating the local office of a multi-national petroleum company that I’ll call BigOil, and that the client wants a very large boardroom table. By chance, they are having a meeting to discuss this at two p.m. Can I attend? Absolutely. I never expected a shot at an actual project on this trip. Home run on the first pitch.

The second stop is an architectural firm. The receptionist takes us to their boardroom, which is dominated by a large walnut table. We could have made it. I’m on my knees examining its underside when my hosts walk in. I scramble to my feet and shake hands with the firm’s owner and his general manager. After my slide show, they comment, “Very nice work. We could have kept you really busy ten years ago. Now there’s not much going on. The recession is still bad. We’re barely surviving ourselves.” Why did they take a meeting with me? Curiosity: they’ve designed a lot of boardrooms and wanted to see somebody else’s approach. We chat, and I learn more about the local market. Nobody in the area specializes in boardroom tables. The local custom furniture market is dominated by much larger firms that offer a full range of products, from upholstered furniture to wall paneling. They promise to contact me if a job turns up, but I don’t think I’ll hear from them again.

Our last stop is half an hour away. During the drive, Bahar confirms that Dubai’s boom has passed. We drive by stubs of roads that terminate in empty desert and the skeletons of partially completed structures covered in dust. Bahar’s descriptions are a variation on a theme: “This was supposed to be a [luxury shopping mall, luxury hotel, luxury international business hub], but the owners went broke.” Even so, we pass small gangs of workers, their heads wrapped so that only their eyes are visible. The forecast today is for a high of 115 degrees. And it’s not a dry heat. They wear pants and long-sleeve shirts, buttoned to the wrist. I wonder what brought them here. I’ve heard that local pay is, by my standards, abysmal. If working in a foreign country under a broiling sun for peanuts looks like a good idea, the other choices must be truly awful.

Our third meeting is in a strip mall. It’s a store selling residential furniture, but there’s no one visible inside. In a back office, we find a middle-age man leafing through a magazine. Bahar tells him that she’s arranged to see Mr. Bubbedin. Unfortunately, Mr. Bubbedin has gone to Chicago. Would this gentleman like to see my presentation? He shrugs. I rip through the slides. He compliments me in a perfunctory way and tells me that I should have been here ten years ago. It was crazy back then, money flowing like water. I take his card, but there’s nothing for me here.

We return to Al Reyami, and in their boardroom we meet representatives from BigOil, Al Reyami, an interior design firm, and the audiovisual equipment contractor. The project manager announces to everyone that they have found someone from America to build the table. I run through the PowerPoint and show them a nifty 3-D model of the World Bank table. Then we start discussing details. The schedule is a potential problem. They’d like delivery in late August but it is already the first week of June. (Shipping from America to Dubai takes about thirty days.) But nobody seems too worried about schedule, so we move to other technical issues. We close by agreeing that I will prepare a complete design after I get back home.

As I’m leaving, the project manager introduces me to a young man who has been sitting quietly in a corner. I’ll call him The Manager. He is in charge of Al Reyami’s woodworking facility, which builds custom furniture and millwork, including all Al Reyami’s conference tables. We will be direct competitors for this job. The meeting was set up for him to present his own ideas for the table, but he was never asked to speak. I apologize to him for taking the limelight. He is very gracious and says that he is quite impressed with my work.

With a few hours to kill before flying to Kuwait, I ask The Manager whether he would be willing to show me his factory. I half expect him to say no, since a tour will reveal the strengths and weaknesses of his work, but he’s flattered to be asked and says that we can go there immediately.

The factory is thirty minutes away. The Manager arrives just ahead of us and dashes inside. We scurry from our car after him—every second in the blazing sun is torture. The office we arrive at is tightly packed with cubicles, each with multiple workers. The Manager explains, “Engineering staff area. All are working on projects.” I ask The Manager how many workers he has, and he tells me about two hundred, give or take a few. Two hundred! That’s a pretty big operation. He tells me that he has 3,750 square meters, about 40,000 square feet. My own shop is 33,000 square feet. I have fifteen workers. Sam’s factory, similar in size to Al Reyami’s, has thirty-six workers.

He runs through a long list of their products: millwork (woodwork that is attached to a building, like custom paneling, doors, and trim), furniture (chairs, accessory pieces, and cabinets, some upholstered), and tables (dining and conference). It would be tough to find a comparable operation in America, producing such a wide range of products under one roof. Our factories tend to be much more specialized. If someone asked me for upholstered work, I would sub it to an upholstery shop, and they would send table work to me. This specialization means that my workers get really good at a narrow range of tasks, which helps amortize the cost of their training. It’s difficult to make money in America if your workers are switching gears all the time. They can never develop a competitive level of skill and efficiency. So you must compensate with low wages, which don’t buy you a worker who knows several trades. It just doesn’t work.

The Manager’s workers all come from India and are hired on a contract basis. He pays a competent bench hand about a dollar an hour. A typical skilled cabinetmaker in the northeastern United States will make about forty-five hundred dollars a month, not including taxes and benefits. For that money, I could hire at least ten decent Indian laborers. I currently have five bench cabinetmakers, who together (should) build between $180,000 and $200,000 a month worth of product. Replace them with fifty good guys for the same price and we’d churn out huge amounts of work.

We arrive at a balcony looking down on the main shop floor, a space as large as my entire shop.

I can see many workbenches, relatively few machines, and a lot of guys out there. I count them: forty-six workers visible. There might be more, as I can’t see all the first floor. Compare that to how many people I have in a comparable area: five. The Manager tells me that they’re producing all the furniture and millwork for an embassy in Ghana. We descend to the shop floor. It’s easily 100 degrees there. Many workers have towels wrapped around their heads to catch sweat. They move at the measured pace of workers accustomed to a long day of physical labor.

The machinery is simple and cheap but of decent quality. The number of tools I see is maybe a third of what’s on my shop floor, and they have at least forty-six workers, and we have only five. I have multiple copies of all my tools so that none of my people have to waste a second waiting for someone to complete an operation. My yearly labor cost would buy me a new shop full of tools every six months, so having extra machine capacity is well worth it to me.

Their work quality is good, but they’re doing it in a different way than we would. They’re using cardboard templates, and all the parts are being hand cut and assembled. We used to do things this way ten years ago, before we got our CNC machine. This factory doesn’t have one.

I notice that lots of workers are just standing around, doing nothing, generally near someone who is doing work. Are they apprentices? Helpers? I give the phenomenon a name: the Stand-Around Guy. An example: three workers surround one who is cutting a part with a hand saw. As the end of the part swings near them, the Stand-Around Guys gently touch it, as if to steady it. When it moves away, they drop their hands back to their sides. They’re pantomiming real work, adding no value whatsoever. Sometimes the ratio of primary worker to Stand-Around Guys is astonishing. I see six guys using a jointer to trim a panel that weighs less than a hundred pounds. One worker could do this, but in my shop, our CNC machine would cut the panel to exactly the right size, and the whole operation would be unnecessary.

We pass through different areas: assembly, sanding, finishing, a carving station, and an upholstery shop. I see Stand-Around Guys everywhere. I also see some very skilled workers—one guy is cutting intricate veneer patterns with a knife (we use a fifty-five-thousand-dollar laser to do this), and another is carving beautiful flowers (we buy carvings from Indonesia). The upholsterers are doing a nice job, and the finish on the furniture pieces is of good quality.

I can’t ask The Manager why so many of his guys are unproductive—it’s kind of a rude question. I’m also afraid to ask whether this factory is profitable. I have one number to consider: The Manager told me that he’d charge about thirty-three thousand dollars for the BigOil table. We can make it for about forty-five thousand, but it will be a very different product. With our CNC cut parts, assembly and installation will be much faster and easier. The Manager’s table will require a lot of fussy handwork. Before we got our CNC, we had spent huge amounts of time fitting top pieces to each other. After we got the CNC, our time for making complex tabletops dropped by more than 40 percent. Adding a sophisticated sanding machine dropped build time another 20 percent.

It’s time to go. We thank The Manager and leave. What a nice guy. I would hire him in a second. Instead, I have to compete with him. His willingness to show me his operation tells me two things: first, that he’s proud of it, and second, that he’s not worried about me as a competitor. He has some huge advantages. He’s local, so he doesn’t have to sprint to meet the deadline. And he’ll be around after delivery to take care of any problems.

On the way to the airport, I consider what I would do if I were running his factory. I’d identify the fifty most productive guys, double their wages, fire the rest, and spend two-thirds of the money saved on better machinery. That sounds pretty brutal, but it’s what has happened in every factory in America—the ones still operating, that is. The alternative for American managers is to take production overseas. And many of them have done that.

The Manager was a smart guy, so he must be aware of the American manufacturing paradigm: buy fancy machines, use skilled workers, and operate with as few of them as you can. Why doesn’t he do it this way? One advantage of his model is lower initial investment. His machines didn’t cost much. And he can lay his guys off whenever he feels like it, cutting his operating costs drastically. That’s a nice option for riding out slow patches, as long as he’s sure of getting a new set of workers whenever he needs them. He told me that his guys get their training in India and that there’s no shortage of people with the skills he needs.

Another thing his model has over ours: lots and lots of jobs. His factory gives two hundred workers a place to go every morning, a way to feed their family, and the pride of making good work. I would guess that the Stand-Around Guys are his B- and C-level performers, who wait for the moment the factory needs a large number of workers, irrespective of their skills. What does the future hold for B- and C-level workers in America? I don’t have any on my shop floor. And the next generation of robots may take out all my A-minus guys, too. The end point of our trajectory is the elimination of people in factories. My biggest marketing struggle is convincing people that our product, which incorporates a lot of hand labor, is worth the extra money. I could come up with tables that require less labor, and sell them for less money. They would be crappy and cheap. A lot of companies have already taken that route, so I’d be entering a mature market where my product is a commodity. Without very deep pockets, I can’t compete that way.

—

I’M IN MY HOTEL in Kuwait at midnight, but too jet-lagged to sleep. At eight-thirty a.m., I meet my minder from the Commerce Department in Kuwait. He’s a short, cheerful man named Fordham Mathai. He was born in Kuwait to Indian parents, which means he is forever barred from Kuwaiti citizenship. He’s a great admirer and now employee of the United States of America. In contrast to Bahar O’Brien, he’s delighted to see me and makes me feel confident that I will succeed. Over breakfast, he reviews our schedule. The firm whose inquiry started my odyssey, back in February, is missing. Fordham says that he could not establish whether they are reputable, so he has left them off the list. Not to worry; he has found many companies eager to meet me.

Approaching Kuwait City from the south, I see its striking, futuristic skyline. We pass a commercial district that Fordham tells me dates to the 1960s. Companies selling similar goods are clustered together: tire shops, auto repair, fabrics, vegetables. It’s a pattern that predates the Internet and presumes that all shopping is done in person. Customers can walk away from one deal and quickly find another. Merchants live and work as neighbors and agree on appropriate price ranges. It works as long as they all have similar costs and are selling to local people. When I started my business, there were several similar districts in Philadelphia. North Third Street was dominated by machinery dealers, and South Fourth Street had a long row of fabric dealers. The Internet and rising real estate prices decimated both clusters. Suddenly these businesses were forced to compete across a national market. Machinery is pretty much a commodity—one can buy the same tool from any number of dealers. The ones who prospered mastered the Internet, carried large inventories, and had easy highway access. The Philadelphia businesses were stuck with cramped, expensive real estate, in a neighborhood that couldn’t accommodate full-size tractor-trailers. They couldn’t carry enough inventory, and shipping was difficult and expensive. Only a single sandpaper supplier remains on North Third, surrounded now by boutiques and coffee shops. I know the owners well, and they’ve told me that they’re still alive because they own the building, they got a Web site up early, and their product is small enough to ship by UPS. The fabric dealers have put up a better fight, because people still want to put their hands on material before they buy. And bolts of fabric are easy to ship, and a lot of inventory can be placed in a small space. But the dealer that I favored, Brood & Sons, closed up when the two brothers got too old to work and couldn’t find a buyer. The fabric business relies on people who know how to sew. Why bother to make your own clothes when they come so cheap from Bangladesh? And why reupholster that sofa you got from Mom when you can spend less for a new one at IKEA?

We arrive at the first stop of the day: a high-end residential furniture dealer. The shop is filled with expensive furniture made by old, established American companies: dark woods, shiny finishes, lots of carving, brass work, overstuffed upholstery, and gilding. Very different from the spare, featureless look that architects love. Fordham and I are greeted by Kipson Jaja, the son of the founder. He serves us tea, and after pleasantries, I give him the spiel. When I finish, he sighs and tells me that I should have been here ten years ago. Back then, his company furnished the many new government buildings in Kuwait. Now that that work has been completed, he is furnishing only private homes. He promises to keep me in mind. More handshakes, promises to keep in touch, and we depart.

The next stop is in a run-down area dominated by auto body shops. Our target’s store is filled with office furniture made in China. We are directed to a second-floor office. Inside we find the boss, a very busy man. He’s got a lit cigarette in one hand, a cell phone in the other. Something is upsetting him, because he’s yelling into the phone in Arabic. Seeing us hesitating at the door, he waves us in and points to a sofa. He ends the call with a curse, I presume, and snaps the phone shut. “I am Kamil,” he declares, as if daring us to argue with him. “You. Sit there.” He directs me to a low stool in front of his desk. I put my laptop on his desk, screen facing him, so that I have to bend over to advance the slides. I start my pitch, and he says nothing while he watches, furiously puffing on the cigarette. I’ve been presenting for maybe a minute when his secretary arrives with a thick sheaf of papers. She’s stuffed into a tight skirt/loose blouse combo. And she’s no shrinking violet. She pays no attention to me or Fordham, but addresses Mr. K in a stream of Arabic, delivered in an angry tone of voice. She drops the papers onto his desk and starts pointing to places he needs to sign, while keeping up a rapid commentary. She’s leaning over his shoulder, and I can see straight down her shirt. I stop my presentation, speechless. Kamil looks up from the papers and glares at me. “Keep going.” So I do. He lights another cigarette. This pause brings the secretary’s volume up another level. She has at least a hundred pages in her hand, and many need signatures. I decide to simply get through this as fast as possible. Then Kamil’s phone rings again, and he holds it with his shoulder, yelling into it, while alternating more signatures with puffs on another cigarette. The secretary never stops talking, nor does she stand up. The view is unavoidable. The only cover she gets are the clouds of smoke that Kamil blows in my face.

When I finally reach my conclusion, Kamil points to the computer. “Go back to start. The World Bank table—how much?” I give him a very large number. It’s a very large table. He scowls and says, “I can get that for a quarter of the price in China. Is all your work so high?” Well, no, I tell him, that was an exceptional job. “Go through slides again.” He stops at a table we made for a company in Ohio that one might find in any office. “How much?” I give him the number. He scowls again. “You are too expensive for me. I can get any of this in China. I am done.”

We head down the stairs in silence. I think to myself, If I can get through that, I can get through anything. Under the worst circumstances, I delivered my message and kept my dignity. I am a real sales professional.

On the way to our third meeting, Fordham tells me, “This gentleman is the top decorator in Kuwait. He has been around for many, many years. Clients are top, top families.” We step off the elevator into a small, beautifully decorated office. The walls are covered with architectural renderings, done in pencil and tinted with watercolor. I was taught to do this kind of work in my architecture classes, back in the 1980s. Nobody does these anymore.

We’re shown into the inner sanctum of our host, Mr. Akil. He’s a short man, oldish, with bronzed skin and a magnificent head of silver hair. A stylish pink silk scarf nestles within his shirt collar. His shirt is open to the waist, revealing an expanse of silver fur to rival his head. A perfectly fitted blue sports jacket, gray slacks, and soft leather slippers completes the ensemble. A decorator, indeed.

I ask him who does his drawings. “Of course it is me who does them!” he says with a smile. “Nobody can draw like this except me!” I ask him whether he is busy. “No, not like ten years ago,” he admits with a sigh. I ask whether he would like to see my work. A smile reappears. “Of course! Did you bring me a book?” I tell him no and pull out my computer. He frowns and asks again, “You don’t have a book? All my suppliers give me a book.” He pulls a beautifully bound volume, with the name of a prominent Italian manufacturer, from a shelf full of similar books. It’s as large and thick as a high school yearbook. I open it and see hundreds of pages of exquisite photographs of upholstered furniture. “It is this year’s book!” he exclaims, the very thought giving him pleasure. “They make another every year. I am the first in Kuwait to get the books.” I apologize for not having a book with me and start showing him the slides. When I finish, he sighs. “You should have been here ten years ago, when they were building the government complex. That work is done now. But I might find some work for you. You must send me your book and I will do what I can.” I tell him that I don’t have a book. “Then you must make one. All the best companies have a book. You will see. With a book, the clients understand what they will get. Send me your book as soon as you have it done. I would like very much to have it.” I make a half-hearted promise to start work on a book as soon as I get back.

In the elevator, I turn to Fordham. “Can you believe that, those books? That’s really old-fashioned.” Fordham smiles. Mr. Akil has made a good living with his books in Kuwait, and me—nothing so far. So it’s something to consider. And reject. I used printed brochures before the Internet came along. And it was an incredible struggle to come up with something convincing. Photography, graphic design, printing: all expensive, all time-consuming. And immediately after printing, it’s obsolete. You can’t change a brochure. The story it tells is frozen at the moment of its creation. A Web site is so much better for us. Instant additions and subtractions, and we can get away with mediocre photography. We can update the text and prices. Potential clients can see it whenever and wherever they want. And it’s been working for us. With limited resources, I don’t want to dilute my efforts by returning to paper catalogues.

Driving to the next appointment, with a man I’ll call The Sheik, I’m suddenly overcome with exhaustion. I doze until we arrive at a low, windowless building. Inside, there’s a surprisingly fancy lobby with displays showing how The Sheik’s grandfather launched an empire, bringing American-made lanterns to Kuwait. Seventy years later, the family runs a multi-billion dollar conglomerate, ranging from retail stores to pharmaceuticals to automobiles to building materials—all American.

Fordham decides to wait in the car and answer e-mails. I am introduced to Kurtis Johnson, assistant to The Sheik. He’s an American, ex-military, here since the Gulf War, and very friendly. I give him the show. Kurtis praises my work and then says, “I need to tell you what’s going on here. I like your work, and I think the boss should see it, but it’s not a good day today. My boss has a kind of difficult situation. He has a large family, many younger brothers and sisters. They don’t participate in the company, but they all have shares, and they want to make sure the money keeps coming. Once a year they have a meeting. That’s today. I’m not sure he’ll be able to see you, but I’ll go talk to him now.”

Kurtis comes back a few minutes later. “He wants to meet you. Right now. Bring the computer.” I follow him into a magnificent conference room, dominated by a gorgeous maple table. I’d be very proud if it came from my own workshop. Kurtis helps me connect my computer to the projector. After a few minutes, people start arriving, all youngish men dressed in robes. I am not introduced to anyone. Eventually the table is filled, except for one seat at the end. And then The Sheik walks in, beaming, hands outstretched to me in welcome. “It’s an honor to meet you, come all the way just to see us!” He turns to the others. “This is Paul Downs, and his company makes very fine American furniture. He will show us his work. Pay attention.” I launch into my show, pleased at such a respectful welcome from such a wealthy and powerful man.

At the end he exclaims, “Magnificent work! Why have I never heard of your company before?” I tell him that we are small and specialized, and give him a very short version of how Google found us and how we became conference table makers. “That’s fascinating. So what do you want from me? How can we work together?” I tell him that I hope he will call me when one of his projects requires a very special table, of unusual size or design. He replies, “There are two difficulties. First, you should have been here ten years ago, when the government was building. We had so many contracts then that we could not keep up. We could have kept you very, very busy. The second problem is that I have my own workshops, and they do all this work for us. This table here. Do you like it?” I tell him that it is superb, the whole room is stunning. “Thank you. Now, I would like to help you. If you could send Kurtis some of your marketing materials—your brochures, your samples, whatever you have—we can see what happens.” I promise that I will get some to him. And then I give him one of the little trivets that we made to give to the people I meet. It’s nice, but not grand. The Sheik reacts as if I just handed him an enormous diamond. He thanks me profusely and announces to the room that this will be a useful addition to his wife’s kitchen. Then he shakes my hand again and sweeps out of the room.

Kurtis and I spend the rest of the afternoon touring some of The Sheik’s furniture stores. At each we’re greeted by nervous store managers, and my opinion is solicited on all aspects of running a store, even though I know nothing about it.

Back in the car, late in the afternoon, I give Fordham a brief recap of the encounter, and he’s very surprised that I met The Sheik. “He is a very important man, very busy. It is an honor for you.” Given the amount of time that Kurtis spent with me, I think that they were trying to figure out exactly who I am, and they erred on the side of respect in case I turned out to be a good potential partner.

Back at the hotel, I eat a stunningly expensive meal and contemplate the day’s events. Can I be a good partner for any of the companies I have visited? They seem to think I am something that I’m not: a much larger company that can provide all the sales support that comes with size—printed materials, samples, and sustained attention from me. I don’t think I can come up with any of those things without making a serious investment in time and money. Which, if the rest of my business disappears, I may have to do. But it’s obvious that the boom days in the Middle East are over and that I would be competing with local companies that have plenty of capacity and are a safer bet for a local buyer.

At ten the next morning, Fordham and I head off to our meeting near the airport. I show my slides to the owner, Mr. Jabril, who represents a prominent American furniture manufacturer. He compliments my work and lists the problems he has getting custom work from his current company. They aren’t nimble, and their engineering on custom jobs is subpar. On the other hand, their standard products are decent and a good value for his market. He asks about my prices, and I repeat the show, with numbers this time. Jabril tells me the same thing I’ve heard everywhere: “You really should have been here ten years ago. I would like to use you, but I don’t have anything right now. If you can send me your brochures and your catalogue, I can start passing them out when we make sales calls. For now, you should probably go to Saudi Arabia and Oman. There’s still a lot of work there.”

At the airport I give Fordham a hug in thanks for all he has done. Kuwait has been a whirlwind, and Fordham has been a pleasant and enthusiastic companion. He did his best to put me in front of decent companies. He’s a credit to the Commerce Department.

—

TWENTY-TWO HOURS OF FLYING and airports: utter hell. I don’t reach my house until midday Thursday, and instead of collapsing in bed, which I’m dying to do, I get my suit back on and have lunch with my family and my parents. It’s graduation day. Peter has completed high school. Naturally, everyone wants to hear about my trip, so I try to describe some of the highlights. But I never did anything very touristy, so I stick with “I met a lot of nice people, and there’s some work there, but it will take a lot of commitment from me to get it. I don’t know whether it was worth it or not.”

It’s a proud moment when my son gets his diploma, made bittersweet because his twin brother is not there. Nancy and I debated whether to bring Henry home for the evening, but we decided against it. He’d get nothing out of the experience, and it would be impossible for us to relax and focus our attention on Peter. Next Sunday, he’ll fly to San Francisco to begin his job.

We get back to our house in the early evening, and I have to excuse myself and go to bed. It’s been a week of very little sleep and I’m collapsing. Friday morning I decide to stay home for the rest of the day. I’m still exhausted, and I can feel a tickle in my throat—a little parting gift from a fellow traveler. One e-mail to work, telling them that I’ll see them on Monday, and that’s it.

On Saturday, I go out to the shop and find it dark and silent, unchanged while I had my adventure. No, wait. It looks much worse than usual. The trashcans are overflowing, the dust bags on each machine are full, and scrap and dust cover the floor. What happened? I have a worker just to sweep and empty the trash: Jésus Moreno, who comes from—Mexico? I don’t actually know. Wherever he hails from, he’s an incredibly hard worker, and he’s done a good job so far. I’ll have to sort this out on Monday.

In my office I contemplate the results of a twenty-thousand-mile quest: a dozen business cards. I enter every contact into our database and send each an e-mail thanking them for their time. After some thought, I decide to tell them that we’re working on printed materials and will have them ready by the end of July, and I promise to keep in touch. I write to Shiva, the interior designer for the BigOil project, my point of contact going forward. My message: I’d like to start designing, but I need their final decision as to how many people they want to sit and a measured drawing of the room. I ask her to forward those documents immediately.

—

ON MONDAY, I steel myself and deliver another dismal sales report. We had only ten calls while I was gone and didn’t book many orders, either. Nick sold a job worth $9,742, and Dan sold two: one to a small ad agency for $5,765, and another worth $4,224 to Eurofurn, for some uninteresting painted panels. It’s not the tsunami of veneered tabletops that I was hoping for. The total, $19,731, is far behind our target of $50,000 a week. We’ve missed our numbers again. There’s a ripple of dissatisfaction from the production workers. They know that the sales team are the highest paid people in the company, and I can feel the questions in their minds: why do they get away with continuous failure? It’s a great question, one that I don’t want to answer because I’m not ready for a civil war between sales and the rest of the shop. I try to end on a positive note. I tell them why I have increased the budget for AdWords, and that I’m sure we’ll see some results soon. And that I’ve just signed up the sales team for training. I take them through the logic of it, starting with Sam Saxton’s results. I finish by saying that the Middle East visit went well and that I even came back with a live prospect that might produce a sizable order.

After the meeting, I ask Bob Foote about the mess in the shop. “Where’s Jésus? I didn’t see him at the meeting. Do you know what happened?” Bob was on vacation last week. He says, “He’s not in yet, but I don’t know why. Should I call Simba?”

Simba is the person who employs Jésus, who isn’t actually on our payroll. It’s an odd arrangement, driven by the fact it’s been much harder for me to hire low-wage workers than high-wage workers. My low-wage jobs are low-skilled, implying that many people should be available. But that pool of workers contains a lot of people with problems—and an even larger group of people who are capable of advancing to better jobs, who leave as soon as they can. Businesses that rely on low-skilled labor must have strong supervision and a rigid system of rules and oversight. And they need to hire and fire constantly. None of my skilled workers needs to be treated this way, so we don’t have such a system. In the absence of said system, the hiring and firing lands on me. And I hate it, and don’t have time for it. What I need is a low-skilled worker who is content to perform a simple, repetitive job, without much supervision, for years on end.

My previous sweepers have been of the “too smart for the job” variety. Bob Foote, for instance, started with a broom, and now he runs my shipping department. Eduardo was the sweeper for a couple of years, but I could see that he had potential and moved him to the bench. I have, on occasion, hired high school students, and they always end up leaving for an easier job or college, even when I pay them twelve or thirteen dollars an hour.

If we don’t have a sweeper, Steve Maturin has the whole crew clean the shop. This takes everyone thirty to forty-five minutes, a loss of at least six hundred dollars in production, three days a week. That’s $93,600 each year. A ten-dollar-per-hour worker costs me about $27,500 in wages and taxes each year and will clean every day. It’s a no-brainer.

Last fall, I tried a different route to filling the sweeper job. There’s a factory downstairs from us with about a hundred employees. A van pulls up to the building every morning and disgorges a load of workers, usually a mix of Asian ladies and Hispanic men. I asked the owner how she found her low-skilled staff, and she directed me to her shop manager, Carl. He introduced me to Simba, the van driver. A young Asian guy, he owns an employment service that leases workers. This is a common way to get temporary employees. Some businesses do this with all their workers, to avoid the complexity of HR and taxes.

Simba provides documentation that all his people are legally eligible to work in the United States, and in return he receives a cut of their wages. He’d be happy to set me up with a good worker, he said. He would charge me thirteen dollars an hour, including all taxes. What was I looking for? I told him that I wanted someone who is physically strong, works hard all day, has good English, and is smart. Simba promised to deliver this paragon the next morning. So that’s how we got Jésus. He didn’t actually speak English, but he did everything else on my list. He followed directions and was an incredibly hard worker. He seemed very happy to be working indoors for a company that treated him like a human being. I didn’t worry about him at all, and Bob Foote liked him a lot. He was perfect. Almost. Jésus has a tendency to disappear now and then, and we can never figure out when this will happen, or what causes it. Simba, when we call him, will say only that Jésus will be back soon and offers another worker if we need one immediately. We tried that once but didn’t like the new guy, and we told Simba that we’d rather wait for Jésus to reappear.

I told Bob Foote to call Simba, and he soon returns with the story. “I talked to Simba, and he said that Jésus is hurt or something and that he won’t be back for a while. Like, months. He didn’t say it happened here, so I guess it’s something else.” We’re both thinking the same thing: good that it’s not our fault, but it sucks that we won’t have Jésus for a while. “Do you want me to call Simba and ask for a replacement?” I tell Bob I need to think about it. Meanwhile, Steve Maturin should have the whole crew do the cleanup. Just like when I fired Eduardo, I can’t help but do some quick math: thirteen dollars an hour, $520 a week, $27,040 a year. And one less person to worry about. I’ve been thinking about matching our labor supply to our reduced workload for the last month, and now two of my guys just laid themselves off. This gives me a little more cash on hand and delays the day that we run through our whole backlog.

I go back to the office and find a bunch of e-mails from Dubai and Kuwait. Mr. Kipson Jaja eagerly awaits my printed materials so that he can start showing my work to customers. Ditto from Jabril and The Sheik. In response to my request for drawings, Shiva says they haven’t finalized anything yet; she’ll send them when she has them. This is a little worrisome, given the short schedule. I sign the checks that were written last week and look at what money came in. We received $47,511 and spent $56,548. My bank balance stands at $98,059. Two-and-a-half, maybe three weeks of operating funds. But all the money everyone owes me comes to only $56,136.

—

ON THURSDAY MORNING, we put together the Eurofurn showroom table for a final inspection. Ron Dedrick has done a nice job:

Bob Foote breaks the table down, wraps each piece in a moving blanket, and heads off to New York. The next morning, I find an e-mail from Nigel in my in-box:

Hi Paul,

Bob installed the VC table today and I would like to bring a few issues to your attention.

- The removable base panels have a very large gap on each side.

- The removable base panels are loose at the bottom and rattle easily.

- The solid wood edging has inconsistent color.

- Gaps on the data lids are overlarge.

I have attached some images of the above-mentioned issues. I would also like to show you this in person and discuss some other areas of concern with the table. When would you be able to make a trip up to the showroom? We have some clients visiting the showroom next week and I would like to resolve this urgently.

I’m furious. His list complains of details required to make the table function properly, except for number three—an inconsistent color is an inherent feature of walnut, the wood they chose. In fact, it’s what makes the wood beautiful. It’s Friday morning; do they expect me to somehow fix all this over a weekend? Are they really unwilling to show my work to a client? I’m so mad, I turn to other projects to calm down. Then I think, Get over yourself. They’re being unreasonable, but you need to work with these people. You need money. Remember Nigel’s promise of a million dollars in the first year? Even a quarter of that would be huge. Think of that. When I finally call Nigel, he is very cordial, but insistent: he wants me to come get the table, ASAP. I agree to drive up tomorrow morning.

Saturday, seven a.m. Midtown is quiet. Nigel is on the loading dock with the disassembled table. He hands me a list with twenty-two changes he wants to make. Most are very minor adjustments to something that was described in the shop drawings and approved. Some are changes to the actual dimensions—the top a little rounder, the gaps in the lids reduced to one millimeter. Others are about how we executed the design, in particular the amount of sanding. A freshly machined piece of wood has edges sharp enough to cut flesh, so we round them over to make them smooth and friendly. This is all done by hand. It’s not something that you put into the drawings; it’s a decision that happens on the shop floor. Nigel wants a sharper look to the edges and corners.

I’m stung by the rejection of a perfectly good table. This has never happened to me before. All the things that we do to make sure a customer knows what he will be receiving—the SketchUp models, the shop drawings, the finish samples, the photographs of similar pieces, the interactions with the salesperson—are designed to prevent what just happened. And they have always worked, including our other jobs for Eurofurn.

I explain our choices to Nigel. He agrees that the decisions we made are sensible, but he doesn’t like the look. I tell him that the only way to make all his changes is to start over again. He shrugs. Will Eurofurn pay us for that? No. I should look at it as an investment in our relationship. He’s got me. I don’t want to walk away. I need customers. So I agree to take the table back and start a new one.

—

MONDAY. I’M SITTING in my office, trying to figure out what to tell the crew. Today is June 18. If we had hit our target, we would have booked $126,000 in new orders. Our total so far: $28,503. The inquiry stream holds no promise, either. Last week we got thirteen calls, but six were garbage. The others are the usual grab bag: three from military units, which have a long procurement process; two from schools, ditto; and two from private companies that might be able to make a decision quickly. A fast order or two would be greatly appreciated. Our backlog is below four weeks.

I fought a gallant battle to limit spending last week. I wrote checks totaling $14,653, but we received only one payment: a deposit check for $4,032. We’re down $10,621 for the week, $49,716 for the year. I have $87,438 in the bank, less than three weeks of operating funds, and another $34,000 in my personal accounts. If we don’t get some cash soon, we’ll run out of money before we run out of work.

I have continued to announce our sales figures and cash position each week. I think I should keep on doing this, even though they are terrible, because a sudden stop would be even more alarming. Nobody benefits when management lets wild rumors circulate. The stress leads to wasted time and sloppy work. I need the guys to continue to produce as fast as they can, without errors. We cannot afford rework. We collect cash when we deliver well-made tables to happy clients. None of our customers knows anything about our troubles. They’re looking forward to receiving their tables, admiring our craftsmanship, and paying us. Those payments delay the day that the doors close, and give us time for something good to happen.

But what if something good doesn’t happen? The thought won’t leave my mind, even as I stand up in front of the crew and go through the numbers. Everyone is sitting quietly, as usual, but paying close attention. I wrap up the summary of cash and sales, then pause. How should I say this?

“I think that everyone can see we are not heading in a good direction. I honestly don’t know what is happening. All the things we”—I nod to Dan and Nick—“are doing have worked for years. I haven’t changed anything big in AdWords. We just aren’t getting good calls. And buyers seem afraid to pull the trigger.”

I pause again. I haven’t let my Monday speeches take such a negative tone before.

“Last time we were in this kind of trouble, in 2008, my partner kept me from telling everyone what was happening until we actually ran out of work. I swore that I would never do that again. So here’s the truth. This is not a good situation. We are running out of work, and we are running short of cash. We’re not done yet, but I can’t pretend that it couldn’t happen. I still can’t believe that we’ll actually have nothing to do. We haven’t had a month with no sales since—I can’t even remember. So jobs are going to come in. The question is, how do we slow down our operations? There are two ways to do it: everyone works less, and gets paid less, or a couple of people get laid off and the others keep working full time. Worst case, the full-time workers take a pay cut. That’s what we did in 2008, and it sucked for everyone. But we survived, and I raised pay back up within a year. I’ll tell you, also, that back then I cut my pay by twice as much as everyone else, and I was the lowest-paid worker in the shop. And this year, I’ve already stopped paying myself. I haven’t had a check since April. But I can’t promise that I can get us out of this myself. It doesn’t save enough money. We may all have to share the pain.”

Total silence. I just gave a speech that could prompt the best workers to start looking for other jobs immediately. I’ll be left with only those too fearful to make a move until there is no other choice. Is there anything I can say that will prevent defections? Or maybe I’m being too negative? Can I expect loyalty in return for my honesty? I have little to lose.

“Here’s what I need from all of you. I’d understand if some of you start looking for jobs. I can’t stop you from doing that. But we’re not dead yet. I need everyone to keep working, and I need the work to be good and the jobs to go out on time, and for us to get paid for the work on our books. If we do that, we have another month or so of money coming in. And another month might make all the difference. Dan and Nick and I are going to be getting special sales training starting in July. We always get a bunch of inquiries from the military in July and August; some of that is bound to come through. I have a project from Dubai that they need in a hurry. Eurofurn keeps sending us orders, and they have promised a lot more. Maybe the World Bank will call us again. I just can’t believe that nobody will buy anymore. I’ve been through this so many times over the years. We’re heading for disaster, just like a truck speeding toward a brick wall. I’ve found that the only thing to do is to keep the gas pedal hard to the floor, and every time, just before we hit it, the wall just vanishes. Something will happen. I’m sure of it.” I pause again, looking around. No apparent reaction to my rousing conclusion. “OK, that’s the meeting. Let’s get back to work.”

I’m heading back to the sales office when Ron Dedrick stops me. “That was a good speech. Thanks for telling us what’s happening. I’ve been through this in other shops and it sucks when nobody tells you what’s going on.” I give him a confident smile, thank him, and assure him that we’ll get out of our bind. “Yeah, maybe,” he replies.

—

DAN, NICK, AND I settle down in front of our computers. I should be doing—what? Proposals? Revisions? Brochures? I’ve reached a state of perfect paralysis. No matter what I choose to do, I should probably be doing something else. And no choice is likely to lead to immediate success. And that drains any enthusiasm I have for doing anything. I need a distraction, but not a pure waste of time. I decide to see whether my increased AdWords budget has had any effect.

I’ve managed to stay away from AdWords for almost a month. Hopefully that’s long enough to see a pattern in response to increased spending. Whatever Google’s data shows, I know that the number of inquiries was worse than it was a year ago and worse than the beginning of the year. Looking at my spreadsheets, I can see that between January 1 and April 1, we averaged 16.23 inquiries per week. Between April 1 and May 20, when I bumped up the budget, that number had dropped to 12.38 per week. And after shoveling more money at Google? Over the past month it declined again, to 10.8 inquiries per week.

I log in to AdWords and see what Google thinks is happening. Since the beginning of the year, they have shown my ads 978,202 times. That’s a huge number. Unfortunately, the viewers of those ads were largely indifferent to my messaging. We got 15,286 clicks—still a very large number of interested parties, but just 1.56 percent of the impressions. I hope that the people who clicked did so because they are eager to buy a table, since each click cost me $3.78, for a total of $57,781. But maybe they were just curious, or clicked by accident. How many of those clickers took the trouble to complete an inquiry through our Web site? Just sixty-five. How many of those sixty-five people actually bought something? I don’t know, because some people just call us instead of submitting an inquiry through our site, and we don’t know which of our buyers did which. I do know how many of my buyers reported finding us on the Web: forty-seven, whose orders total up to $668,816. That’s 80.4 percent of our total sales, $831,777. All my other efforts to drum up work have not amounted to much. I really, really need AdWords to come through for me.

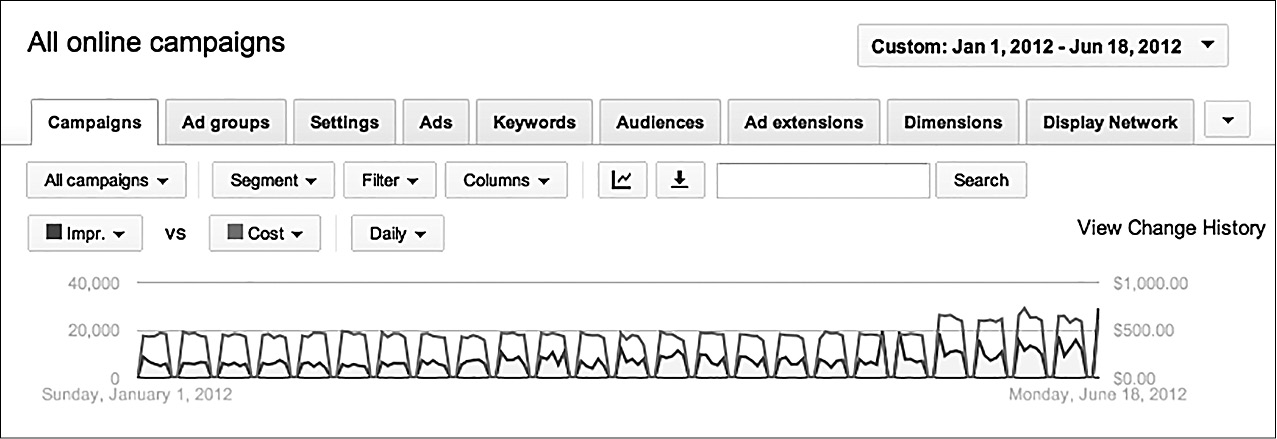

After an hour, I stumble upon a graph that appears to answer my questions. I am looking at the pattern of daily spend and daily clicks from January 1 to June 18. Since I don’t buy ads on the weekends, the graph looks like a long line of haystacks in a flat field:

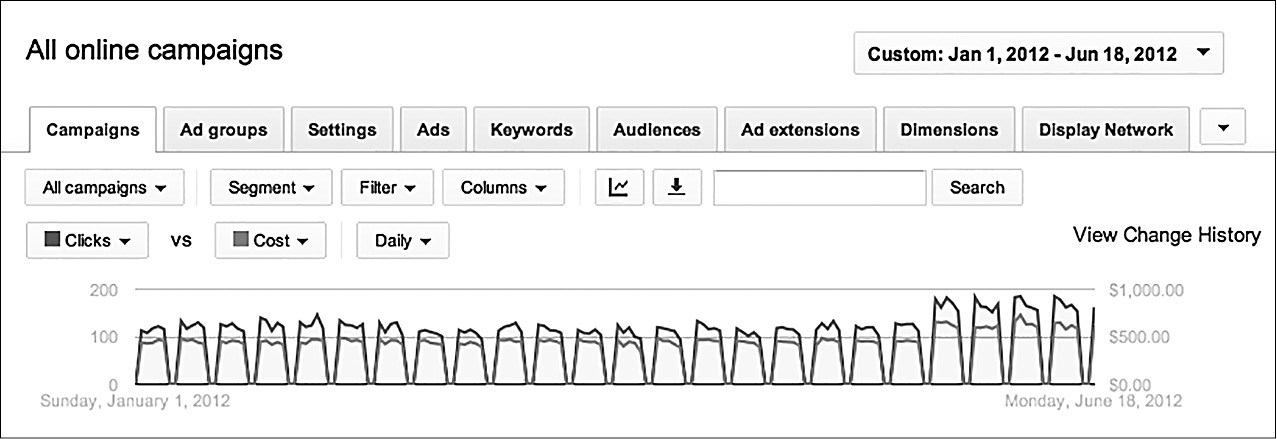

On the day I increased the budget, toward the right side of the graph, the number of impressions jumped up sharply from about six thousand to ten thousand. The highest totals come each Monday, and the highest total of all happened on the Monday after I increased the budget: 18,626 impressions. It’s weird that the impressions drop off each week after Monday, with an occasional reversal, but always declining from a peak at the start of the week. That’s not what I see in my records of incoming calls, which average 2.58 per day on Mondays, rise to 3.65 on Tuesday and 3.54 on Wednesday, and then drop back to 2.50 on Thursday and 2.55 on Friday. Hmmm. I rejigger the interface to show cost versus clicks:

It’s the same pattern: more spend leads to more clicks, but those clicks decline throughout each week. I look at one last combination, costs versus the number of people who e-mail us an inquiry. These are called conversions:

This view corresponds to our reality. The increased spend didn’t change the number of conversions, and the total for the past two months has been lower than it was at the beginning of the year. The increased spending hasn’t done anything for us, yet. But why not? Google has delivered what it promised to do: more impressions, more clicks. But that isn’t translating into calls and sales. What is happening? I’m stumped.

I hear a happy clap of hands from Nick. He has just closed a deal, worth $11,599, to a biotech company in Texas. Maybe this will be the start of a turnaround. At the end of the afternoon, he closes another deal, worth $8,063, to a school in New York City.

On Tuesday morning, Dan starts off with a small deal worth $3,380, for refinishing a table we built before the crash.

My first task is to deal with the Eurofurn prototype. I take Nigel’s list of twenty-two changes to Andy Stahl. Leaving out my feelings of anger and humiliation, I tell him what happened on Saturday and ask him to make a revised set of shop drawings with all twenty-two changes. He completes them by mid-afternoon and sends them off.

As soon as Milosz approves the new design, which is almost identical to the old one, I take the drawings out to Ron Dedrick and go over them. He greets me with a wry smile. “Didn’t go so smooth?” I sigh. He’ll start the new table in the morning.

Later that day, Emma drops a thick envelope on my desk. It’s the results from the sales aptitude tests. The package contains two items: a slim folder and a very thick binder, titled “Impact Analysis: Paul Downs Cabinetmakers.” Inside the folder are two reports written by an outfit called Objective Management Group. The first is titled “Sales Manager’s Self-Assessment for Paul Downs”; the second is called “Extended DiSC Personal Analysis Report: Downs, Paul.” Thirty-nine pages devoted to sales management, and thirty-six pages all about me.

I riffle through both. Lots of colorful charts and graphs, a fair amount of text. Then I pick up the binder. It’s divided into seven sections, totaling 284 pages. Charts, graphs, text, footnotes. I quickly page through it. My reaction is a mix of skepticism and fascination. Skepticism: this is just boilerplate ginned up to make a bulky pile that looks like it’s worth the eight grand I’ve spent. Fascination: this is about me. Paul Downs. Hopefully, this is all focused on my business and my problems. It will be different from the coaching I’ve been getting from Ed Curry and my Vistage group, because it’s objective, just based on our answers to the tests. My sessions with Ed are conversations, with all the limitations of any dialogue between two people. There’s lots of stuff I don’t want to talk about with him, and there’s probably a lot in his mind that he wouldn’t say to my face. This report is supposed to jump over those social boundaries and give me the truth.

I start reading the sales manager booklet. Its opening is in the form of a letter, with a bold-faced heading: “The Dave Kurlan Sales Force Profile™.” “Dear Paul,” it begins. “Blah de blah de blah blah blah.” I read paragraphs of what purports to be a personal letter to me, complete with Dave’s signature. There’s a heaviness to the prose, an inclusion of extra words, sentences, and paragraphs that extend the size and length of the document without adding much extra useful actionable information of any worth or impact at this time. And he keeps referring to me as the “sales manager.” I’m not the sales manager. I’m the boss.

After finishing this letter, I’m drooping inside. I have to wade through hundreds of pages of this sewage? Did I just shell out all that dough for boilerplate? I answer my own question: you’re in no position to reject advice. There’s got to be something of value in this report. Now plant your butt in a chair and find it.

This doesn’t happen while I’m at work—my day is swallowed by picayune administrative tasks. So I take the reports home. By midnight, I’ve read it all.

The first section, assessing my prowess as sales manager, bears bad news. I stink at this job. The long list of the things I’m doing wrong falls into two groups. First, we make a large number of tactical errors trying to close deals, beginning with my basic procedure of sending a proposal in response to every inquiry. And second, I don’t manage my sales staff the way I should. Here the deficiencies are many and troubling: I am not constantly looking for new sales staff. I don’t have a written sales plan. I don’t ask my guys to keep records on each prospect. I don’t make them document what they do all day, so I don’t really know if they are being productive. I accept their excuses when deals disappear. I don’t hold them accountable. I let them get away with failure, even though it’s slowly killing us. I need to set standards and enforce them, and get rid of the people who can’t cut it.

The sales manager assessment does nothing to bolster my confidence. But rather than weep in my beer, I move on. The next section is my personality profile. The premise of the DiSC assessment is that every person’s personality is a mix of four different tendencies. “D” is for Dominance, a confident, competitive person who wants to get results and focuses on the bottom line in every situation. “I” is for Influence, a person who is concerned with persuading other people to go along with his plans, who values openness and maintains relationships well. “S” is for steadiness, a person who places emphasis on dependability, sincerity, and cooperation. And “C” is for Conscientiousness, a person who focuses on quality and accuracy, expertise and competence. It might as well be C for “Craftsman.” In every person, one tendency will be primary and the others subordinate to a greater or lesser degree.

In each category, the report has given me a positive or negative score, ranging from +100 to -100. As you might expect, my Dominance score is highest, and I have positive Influence and Conscientiousness scores as well. My Steadiness score is negative 100. Yup, they pretty much nailed me. I do like to be in charge, and I don’t like to work alone. And look at the work that I have chosen: a woodworker, who cannot be anything but Conscientious. A Craftsman. The test is correct about my weakness as well. I am not Steady. I don’t enjoy routines or being part of a system. I am not a rule follower. I’d rather write them myself and get other people to follow my plan. And that is what being a boss is all about.

There are lots of detail about how my personality plays out in my business life. Specifics about things that I will enjoy doing and things that I will find difficult, and warnings about how my interactions might be perceived. I should listen carefully and explain my decisions to people. I can be inspiring if I want to be, but I can also leave others frustrated if they don’t understand why I am doing what I am doing. Because I dislike routine, I might avoid creating systems for my business that will allow it to operate without my constant intervention.

The executive summary shows how my company’s sales organization ranks compared to the typical company. Again, my sales management skills are non-existent and our selling skills are terrible. But I get a little encouragement—my salesmen have serious problems and it would be reasonable to fire them both, but they might also respond to training and succeed. The thing we do best is gathering leads. Our Internet efforts consistently bring in new inquiries. But the report is based, in part, on Dan’s and Nick’s perceptions of how our operation works, and I don’t think that they understand that our AdWords campaign has stopped functioning.

The next section is stuffed with confusing charts and graphs, and points out Dan’s, Nick’s, and my failings in detail and at length. It boils down to: none of us knows what he is doing, and I don’t hold them accountable when they fail. The next three sections detail those assertions and close with a summary of our strengths and weaknesses. My profile tells me that I am a good decision maker, have a strong self-image, control my emotions, don’t give up, want to succeed, and have a realistic attitude toward money and buying. My weaknesses fall under two headings, my failures as a salesman and as a manager. As a manager, I accept mediocrity from my salespeople, I don’t know how to hire, I don’t replace my worst performers, I don’t spend any time managing them, I jump in to salvage a sale instead of letting them learn from their mistakes, I don’t have any idea what motivates them, I don’t have any regular meetings to track progress, I don’t coach them, and I don’t do follow-ups to find out what happened when they fail. I’m still spending a lot of my day as a salesman, and here’s how I’m screwing up that job: I don’t follow any consistent sales process; I don’t have any idea who I’m dealing with and whether they have the power to make a decision; I talk too much and listen too little; I’m vulnerable to lies my customers tell me; I don’t know why my prospects want to buy; I don’t try to get the prospects to agree to make a decision; I don’t try to form a relationship with my prospects; I send proposals too soon; and even when I make a sale, I don’t follow up or ask for referrals.

Dan and Nick have similar lists, but with a surprising twist. Dan is the most likely to succeed as a salesperson. Apparently Nick lacks motivation and isn’t interested in money. I’m not sure I believe that, but I have to admit the report has painted an accurate picture of me; maybe it’s uncovered hidden truths about Dan and Nick as well.

When I finish, I feel like I’ve been punched in the gut. My cavalier dismissal of the report has given way to a recognition that we have big problems and a long, long way to go to fix all of them. So now what? We’ll do the training and give it all we’ve got. But will we survive long enough to complete the training if I don’t make changes immediately?

What can I do, what can I do, what can I do? I’m riding my bike into work the next morning, and the question loops in time to my pedal strokes. About halfway through the ride, an answer appears: cut commissions, commissions, commissions. I can send Dan and Nick a strong message by keeping their portion of incoming payments. It’s not a huge amount of dough—just 2 percent of the money that we get from sales—and they will still have their salary to live on.

By the time I arrive at the shop, I’m convinced that this is a great plan. But just in case I’m wrong, I review the numbers. I can see on my bank’s Web site how much yesterday’s payroll will cost: $23,606. We’ve received three payments this week, totaling just $14,234. I have $78,035 left in the bank. The payment on our credit card, $20,585, goes out tomorrow. After that, I’ll have just $57,450. And I have another pile of bills to send out on Friday, totaling $8,255. Once that’s gone, I’ll have $49,195. I look back at how much we’ve been spending per week since April 1: $38,086. So now I have less than two weeks of funds, unless I simply stop paying my bills.

My spreadsheet shows four incoming payments this week, totaling $18,077. Three of those four are final payments from jobs we shipped in May. The other is a deposit from a state university that placed an order in April. We’ll probably get the first three, but the deposit payment might be delayed in the university’s bureaucratic processes. Theoretically, no deposit should make me put the job on hold, but if I do that, the shop will run out of work sooner. After that, there’s very little on the horizon. My total cash-to-come amount is just $50,751. But we won’t see any of that until we finish those jobs, and that will take more than two weeks.

I check to see how much I have paid Dan and Nick in commission. Lately, it hasn’t been much. In yesterday’s paycheck, they each got $2,384 in base pay, pretax. Nick also received commissions totaling $464, again before taxes. Dan’s commissions added just $97. These commissions aren’t much compared to what they have already received this year. Nick’s commissions total $9,145; Dan’s sum up to $4,544. I paid myself commissions totaling $4,612 in the first quarter, but I haven’t taken base pay or commissions since April. It’s time for them to feel some of my pain.

I know from experience that announcing a pay cut is no fun. And this time, the pay reductions are not being shared equally by all workers. I just want to do something to put a little fear into the sales guys. Taking away their commission won’t save much money; but every little bit counts when we have only two weeks of operating cash on hand. So I decide to emphasize the financial case for this action.

It’s eight-thirty in the morning. Nick and Dan are working on projects. I ask them to stop for a moment and start with a question: “Anything coming in today?” Dan and Nick look at each other and shrug. Nope. I keep going. “OK, that sucks. Because we have a big problem. We’re running out of cash. We’re going to be down to fifty thousand dollars by the end of the week, and that’s just enough to run for two weeks. I need to cut our expenses, right now.” Nick is staring at me. Dan is frozen, and he’s starting to turn red. He probably thinks I’m going to can him. I see his reaction and think to myself, No, Dan, I’m not going to fire you. When you see me set up a camera, and ask your permission to film the meeting, then you have reason for fear. But not today.

I announce my plan: “I’ve decided to cut out the commissions. As of right now. I need every penny of the incoming cash, so I’m stopping the two percent payments.” Now Nick looks angry, and Dan sags with relief. I continue, “I haven’t taken a paycheck or a commission payment since the beginning of April. And I just committed to spend thirty-seven thousand dollars to make us all better salesman. And”—now I tell a big lie—“I’m absolutely sure that the training is going to work, and we’re going to come out of this. But I don’t know how long it will take. Probably a couple of months. And I need to keep the doors open until then.”

Nick asks a sensible question: “You’re cutting commissions forever? How long are you going to keep doing this?” I don’t know. I haven’t really thought about it, because it seems more likely that we’ll be out of business before I have to deal with that question. “I can’t say. Until things get better. Until we make some sales. Until I can afford it.” Dan asks, “What about our salaries? Are you going to cut that, too?” I tell them that I would prefer to avoid this, but if things get worse, it might happen. “So let’s not let things get worse. Sell something. And when the training starts, put some effort into it. I’m committed to the program. Remember, it worked for Sam Saxton. I’m sure it’s going to work for us.” If we have anybody to pitch to. I’ve put the fear of God into the sales guys. But I haven’t figured out where the customers have gone.

—

WE ALL SIT and start working again. There’s an e-mail from Shiva in Dubai. Finally, the drawings from BigOil are here. I can see that the table is big enough to accommodate thirty-eight chairs. But there’s no indication of the materials, the base, or even where the wires coming from the floor (or ceiling?) will go. I can’t do anything with them. I have one other drawing that I was given at the first meeting. It purports to show the structure of the table. Like many drawings from architects, it shows something unbuildable, and the design doesn’t even make sense. The base is far too small to support the top, and it’s in the wrong position—nobody would be able to pull up to the table without hitting their knees. So I have two drawings from BigOil, but not what I need to make a proposal. Do they still want this table in Dubai by the end of August? If so, we have to build it by the middle of July. I e-mail Shiva, asking for the missing information. I’d love to get this job—it will be worth at least forty thousand dollars—but I’m stuck.

The next day there’s a small reprieve. Hiding in the junk mail I find a check for $1,556. Whoopee! Enough money to run the shop for a couple of hours. Unfortunately, I just sent out bills totaling $8,255. I log in to AdWords again and stare at the same mess of links and data. The Web site won’t even allow me to directly compare two time periods in the configuration I want to see them in. Should I stop the campaigns to save money? On the face of it, the $650 I’m chucking at Google every day is a waste. It’s not producing anything for me. On the other hand, in all my other years in business, spending money on advertising has been a good investment. My sales have gone up every year except for 2009. I haven’t made many changes to the campaign in the past two years, and we’ve seen steady growth in sales until very recently. But maybe this is the moment to stop spending money on the Internet, and let my organic search results do the heavy lifting. Am I wasting precious cash? The only way to find out would be to pause the campaigns and see what happens. But last July I got a call from a bank in Washington that led to a quarter million dollars in business before the end of 2013. One call. A quarter million. Did they pick up the phone because they saw my ad, or because they clicked the free link? And if I hadn’t been running the ad? Would Google still give me good free results? They claim that there’s no connection between the ads and the organic links, but that hardly seems credible. They’re a business. If I were them, I’d give a boost to the Web sites that pay me money. I’m afraid that if I stop paying, my free links will drift down the page to obscurity, and then I’m out of business. I can’t take the risk of losing a single customer right now. Cutting the ad spend will be the last thing I do.

—

WHILE I’M STARING at my screen, I think of a way to show what might have changed in the campaign over the past two months. With our wide-format printer, I print out screen shots showing the performance of all fifty-five ad groups on one piece of paper. Finally, I’ve found a way to see all the numbers at once. I print the six-month period from August 1, 2011, to February 29, 2012, when the AdWords campaign worked well, and the report from March 1 to June 20, when it’s been failing. I tack them up on the wall outside my office. Each report is two feet wide and more than four feet long, and shows my fifty-five ad groups, each with fourteen associated data points. I start marking up the printouts, dividing one data point into another, and then comparing that to the same calculation from the earlier time period. Nothing jumps out at me. Finally, alone in the office at six p.m., I give up and go home.

Early the next morning, when I look again at the printouts, only two facts seem important: the Boardroom Table ad group, which was producing the most e-mails, has dropped off, and the Modular Tables group has had a big bump in traffic, but produces very few e-mails. Overall, more people see our ads, but the number of people who call has gone down. That fact isn’t on these pages, but I have other records that document the decline. Is there something going on that isn’t in any of my records?